![]()

![]()

WHY DID THE PEOPLE I WANTED TO CONSIDER as high priests of knowledge not go to Orvieto? Is it just possible that what the Karpes would have seen might have been too much to take?

Had they made the trip, it might have been unfathomable afterward to retreat into their world of library books. Their temperance might have evaporated, the even keel replaced by tumult. For they would have had the uncomfortable experience of understanding all too well what it was about Orvieto that was too much for Freud to remember in its entirety.

Come on, Karpes. Get past the first three letters of Signorelli to the first six. And you have the word Signor. Mr., Monsieur, Herr, Señor: Whatever language you translate it into, it’s the title for a man.

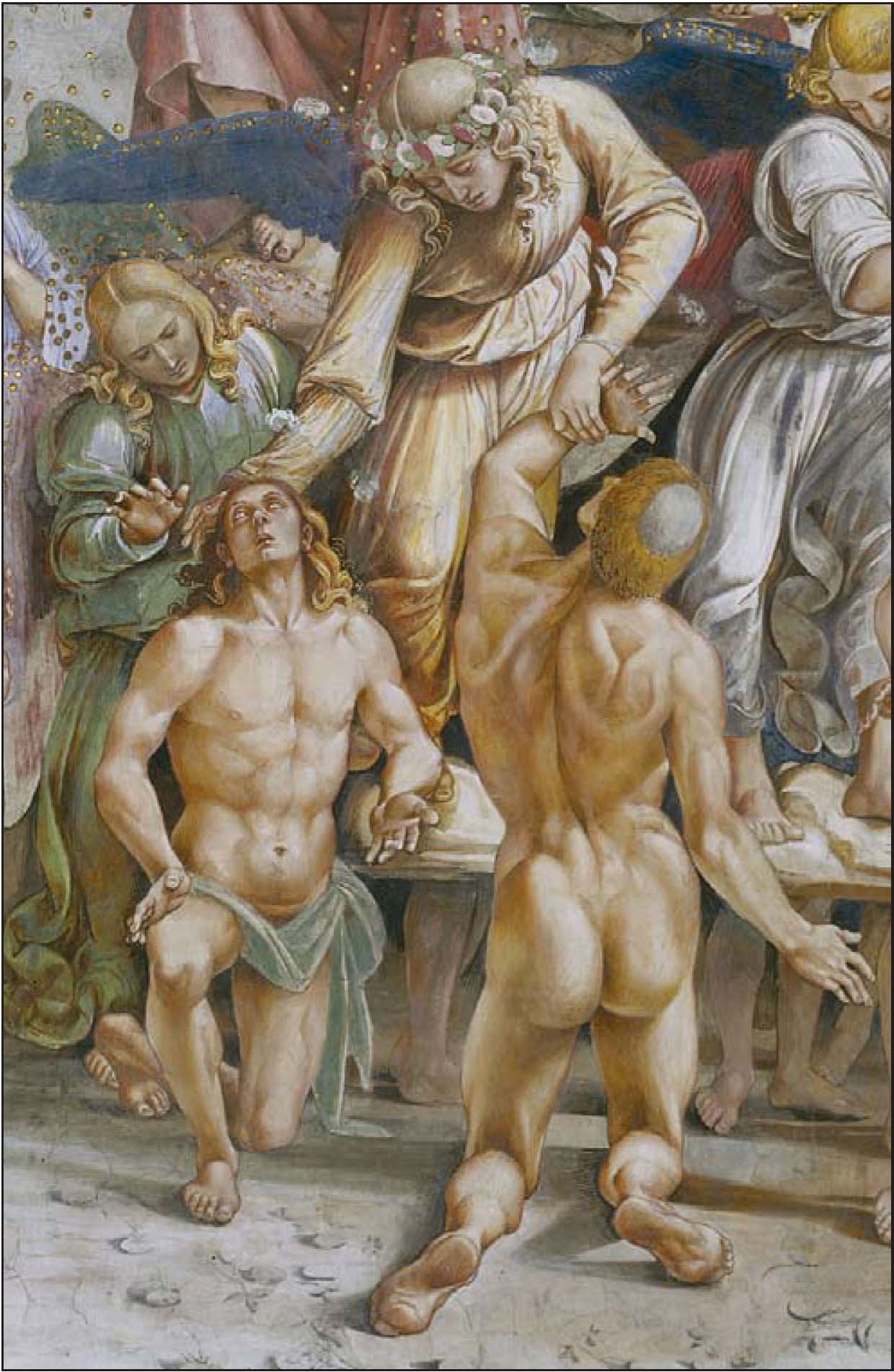

And then look at Luca Signorelli’s The Elect. Closest to the viewer, in this fresco on the wall of the altar bay, there are, spaced toward the bottom of the composition, five naked or nearly naked men, the soles of whose feet seem practically in our faces. Each is a more perfect specimen than the previous one of the hefty, muscular type of male built like a gym model. Why they are the elect we do not know—except that they are more fair-skinned and blond than the equally fit fellows who are damned. Perhaps that baby skin on their very mature bodies confers innocence or virginity on them.

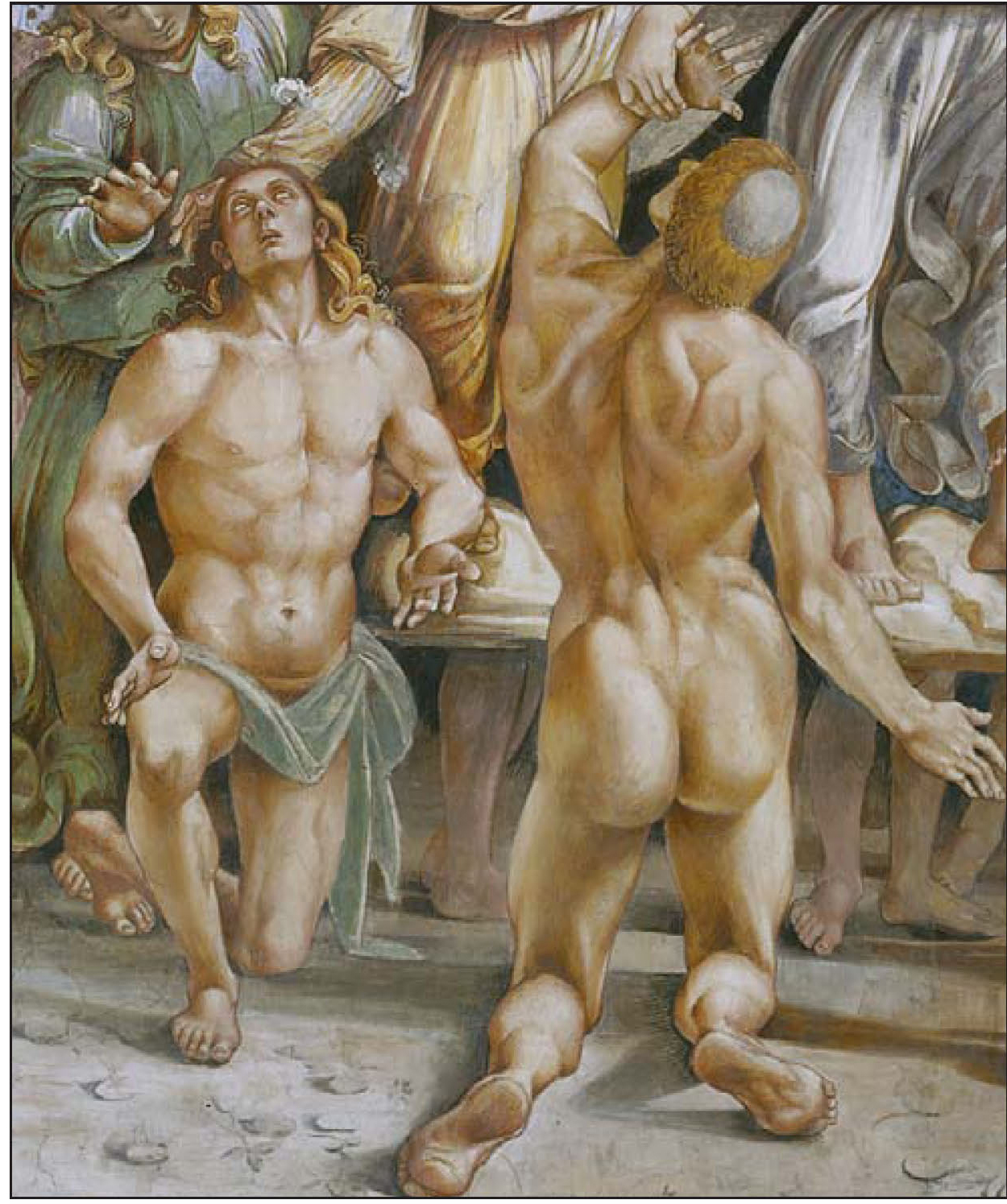

The one who catches our eye first is a fellow on his knees. He turns away from us as he extends his left arm to a beatific-looking angel who will lift him into paradise. [plate 31] Perhaps he has gained the right to go there because he developed his physique to such perfection; he is enormous, but all muscle and no fat. Signorelli has painted his rear end with the same intense pleasure that Titian would reproduce women’s breasts; one has the impression that the artist has created his ultimate object of lust. On each well-rounded buttock, the area nearest to us is bathed in sunlight, with darkness accentuating the globular slope up toward the hips. The crack is even darker, a near black that is eye-catching; there is no avoiding looking at it. [plate 32]

Plate 31. Detail of The Elect

Plate 32: Detail of The Elect

This remarkable specimen of masculinity is at the peak of life—that brief moment between youth and age when athletes reach their prime. Everything about him—his legs and arms, his tapered back, even his massive hands—has been developed to perfection. His golden curls, which resemble Signorelli’s own, add to his spectacular appearance.

He is only one of Signorelli’s dream men. The angel gives its other helping hand to a second idealized male specimen, this one seen from the front. With his long hair and the completely spaced-out look on his face, this guy could best be likened, today, to a gorgeous male hippie. The artist has decorously draped a robe across his middle so that his genitals are concealed—penises and balls are less Signorelli’s thing than are asses—but the viewer is invited to admire, besides an impressive naked chest, his entire abdomen, including a thin line of body hair that begins below his navel and extends to his pubic region, of which the top part is on view.

Lest the viewer be deprived of any possibility of male modeling, further strapping specimens in the foreground of the fresco display their bodies from other angles. One of these naked men, standing, has his hands lifted above his head in prayer; beyond its spiritual purpose, the pose enables him to push his backside outward to be admired. His buttocks are formed to perfection; again Signorelli has used light and shadow to accentuate their every nuance. Like all the figures, this one has practically no body hair whatsoever—the better to reveal the forms. [plate 33]

As for the few women in this painting: Andrea and I agreed that, while there is no question as to their gender, their breasts look like add-ons, disproportionately small for their hefty physiques. Their hips are distinctly female, and the curves of their bodies provides a degree of softness, but they are definitely women of the rugby player type, and we get no sense that Signorelli painted them with any real feeling.

Plate 33: Detail of The Elect

Assuming that Freud understood the narrative program in this depiction of earthly paradise and identified the characters in it as the elect, he would have known that these fortunate creatures en route to salvation are presumed to be in a state of innocence. Signorelli’s alleged intention was to show all these splendid specimens of male nudity, and the three naked women who are stuck in among the more than a dozen stripped-down men—there are, in addition, some characters in the second tier who may be either men or women, but we cannot be sure which—as devoid of lust, and therefore pure. Dugald McLellan words it nicely: “The perfectly formed, naked, and unadorned body, free from the trappings of worldly existence, best symbolizes the purged will that is at last ‘free, upright, and whole,’ after having passed through the rigorous but restorative process of purgation.”

The angels who are lifting the elect upward, and who function as God’s agents, have already achieved this state of grace. Playing their lutes and harps and lira da braccio, with at least one of them visibly singing, they create glorious music for the figures who will enjoy “the final release from the torments of the flesh” and enter “the heavenly realm.” The red and white roses with which the angels closer to earth are showering the elect are symbols of chastity.

The message was that to forsake sex is to enter paradise. Those flowers will never die; rather, they will remain perpetually in full blossom. Spring will last forever.

Did Freud understand these layers of meaning? To what extent did he connect this imagery with his own experience? Mourning his father’s death—and, as most people whose parents have died understand all too well, imagining his own end in a new way (the natural coefficient of grief as we become the oldest surviving generation of the immediate family)—how did he feel about the idea, fundamental to Catholicism, and to these frescoes, that the original sin is what made humankind mortal to begin with? What did Freud, who attributed so much of the human psyche to the way the sexual drive is or is not realized, make of Signorelli’s illustration of the belief that to divest one’s self of sexuality is the requisite of achieving paradise on earth?

In Signorelli’s hands, that familiar theme has taken new form. For the painter has made the elect his dream men; he has created what he apparently cannot resist. In presenting men liberated from sinfulness, he has invited and demonstrated his sinfulness.

And while he has shown idealized male specimens who are deliberately sexually alluring, he has gone to scant effort—or tried and failed—to include in the group the sort of women who would most attract heterosexual men. I am at a loss to say whether Signorelli’s burly and muscular females appeal to lesbians, but they have scant allure to most males who prefer ladies. Nor do I think that Signorelli’s men are of the Chippendales, Playgirl variety. Heterosexuality is beside the point in the paintings at Orvieto; in these illustrations of sin and punishment and abstinence and reward, the longings are always of men for men. How the viewer reacts depends on the viewer’s own inclinations, but there is no question as to the nature of the attraction that pervades these paintings.

Freud certainly hit the nail on the head when he wrote that “the topic of death and sexual life” was “by no means remote” here.

IN AN ESSAY HE WROTE IN 1914, “The Moses of Michelangelo,” Freud attempted to define his relationship to paintings: “I may say at once that I am no connoisseur in art, but simply a layman. I have often observed that the subject-matter of works of art has a stronger attraction for me than their formal and technical qualities, though to the artist their value lies first and foremost in these latter.”

It’s easy enough to apply this to the Signorellis. Aesthetically, they are excelled by many other Renaissance paintings. It is their subject matter that rivets the viewer, and that certainly counted more for Freud than did ideas of design or color orchestration. But if they were not painted as well as they are, the frescoes in the Cappella Nova, however thrilling their imagery, would not have lured the father of psychoanalysis. The vigor and deftness with which Signorelli renders his Herculean men is what makes these characters so powerfully present before our eyes. Had these identical scenes been conceived with less engagement in their visual qualities, and less sheer proficiency, they would not make nearly as strong an impression.

In the 1914 essay, even as he tries to minimize the importance of style and aesthetics—“I am unable rightly to appreciate many of the methods used and the effects obtained in art”—Freud at least recognizes that his own response to art is not entirely straightforward, and eludes full comprehension. When introducing the topic of Michelangelo’s large marble sculpture of Moses and his reaction to it, Freud admits that he seeks understanding of the reason art has its impact, and is uncomfortable with leaving it as an enigma. “Some rationalistic, or perhaps analytic, turn of mind in me rebels against being moved by a thing without knowing why I am thus affected and what it is that affects me.”

Yet when he cannot explain the mystery of the way great art can penetrate the soul, he accepts the conundrum, almost to the degree of exulting in it. “This has brought me to recognize the apparently paradoxical fact that precisely some of the grandest and most overwhelming creations of art are still unsolved riddles to our understanding. We admire them, we feel overawed by them, but we are unable to say what they represent to us.” When he wrote this in the essay on the Moses seventeen years after observing his inability to recall Signorelli’s name—a prime example of being “overawed”—was he thinking about Orvieto? Was he seeing as an “unsolved riddle” the idea that the Signorellis had made such an impression on him that the intense emotion rendered him unable to remember the artist’s name? It seems that this is a rare instance of Freud saying that certain things in life can never be understood.

Yet what Freud subsequently says in the Michelangelo essay could be applied, I believe, to Signorelli’s Orvieto frescoes and his own reaction to them. “In my opinion, what grips us so powerfully can only be the artist’s intention, in so far as he succeeds in expressing it in his work and in getting us to understand it. I realize that this cannot be merely a matter of intellectual comprehension; what he aims at is to awaken in us some emotional attitude, the same mental constellation as that which in him produced the impetus to create.”

Who among us, who actually looks at the frescoes in the Cappella Nova, can doubt that Signorelli’s intention, at least in part, was to create, in as many variations as possible, his male ideals? If these specimens were not to be savored as objects of sexual attraction, at the least they were to be admired for their physical impressiveness. Few more effective examples of power and masculinity, of the effects of testosterone, have found their way to a painted surface. Spectacularly robust, beautifully toned, totally at ease in their nakedness, these athletic men “awaken” in their viewers some of the same “emotional attitude” with which Signorelli painted them. The person who best enables us to understand that process whereby it is the intention behind an artist’s presentation of his chosen subject matter that has a profound impact on a viewer, and who therefore causes us to grasp some of what lay behind Freud’s parapraxis, was Freud himself.

FREUD HAD A BRAVE WILLINGNESS TO ADMIT IT when he could not come up with an answer. To the extent that I can comprehend it, in his first published paper, “Observations on the Form and Finer Structures of the Lobular Organs of the Eel, Organs Considered to be the Testes,” which appeared in 1876 in the Mitteilungen der österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, he allowed that he could not solve the issue of how the unconscious was part of a dynamic system governed by the laws of chemistry and physics—as adumbrated by the recently developed concept of psychodynamics. To try to understand the mating habits of eels, when, as a twenty-year-old medical student, he was at the zoological station the University of Vienna maintained in Trieste, Italy, he dissected some four hundred of these slithery sea creatures but failed to find the organ he’d expected to locate. (He did not know that eels develop genitals only when they need them, and that eels breed about three thousand miles from Trieste.) It strikes me as more than a coincidence that the source of inexplicable mystery had to do with maleness.

I FOUND AND READ A LETTER THE TWENTY-YEAR-OLD FREUD wrote to a friend about the research on eels’ testicles in part to determine if I had fallen for a spoof, as the title of his essay and the name of the publication seem more parodic than real. But Freud really and truly studied eels’ testicles in Trieste, and wrote about them to Edouard Silberstein. What bowls me over about the letter is the lightheartedness with which young Freud conducts his investigation and the way his drawings resemble Paul Klee’s. To be as free-spirited and aligned with the larger cosmos as Klee was has always been one of my ideals in life. One of the greatest of the many strokes of good luck I have ever had was in coming to know Anni and Josef Albers, and while Josef was a teaching colleague of Klee’s at the Bauhaus and made, for the rest of his life, art that bears the lasting influence Klee’s vision had on him, it was Anni who admitted quite simply that Klee was her “god,” and who smiled broadly whenever she said his name. Klee was brilliant, undaunted by any sense of shibboleths, as childlike as he was intellectually sophisticated, and magnificently alive to the beauty of life in infinite ways. The Alberses, through Josef’s photos of Klee frolicking on holidays and Anni’s stories of his playing music, made him personally alive to me, but it is Klee’s art, from the puppets he made for his son to the simplest drawings to the luminous watercolors to the magical large oils, that makes me feel that his achievement is in many ways like human life in its entirety: the cruelty as well as the wonder, but mainly, in spite of the horrors he honestly presents, the magnificence.

HERE ARE TWO PAGES OF FREUD’S LETTERS translated into English:

Every day I get sharks, rays, eels, and other beasts, which I subject to a general anatomical investigation and then examine in respect of one particular point. That point is the following. You know the eel [fig. 12]. For a long time, only the females of this beast were known; even Aristotle did not know where they obtained their males and hence argued that eels sprang from the mud. Throughout the Middle Ages and in modern times, too, there was a veritable hunt for male eels. In zoology, where there are no birth certificates and where creatures “according to Paneth’s ideals” act without having studied first, we cannot tell which is male and which female, if the animals have no external sex distinctions. That certain of their characteristics are in fact sex distinctions is something that has first to be proved, and this only the anatomist can do (seeing that eels keep no diaries from whose orthography one can make inferences as to their sex); he dissects them and discovers either testicles or ovaries [figs. 13 and 14]. The difference between the two organs is this: the testicles can be seen under the microscope to contain spermatozoa, the ovaries reveal their ova even to the naked eye [figs. 15 and 16].

Recently a Trieste zoologist claimed to have discovered testicles, and hence the male eel, but since he apparently doesn’t know what a microscope is, he failed to provide an accurate description of them. I have been tormenting myself and the eels in a vain effort to rediscover his male eels, but all the eels I cut open are of the gentler sex [fig. 17]. That’s all I have to tell you for now

Your Cipion

The drawings Freud used to illustrate and then describe his research in Trieste to his friend Eduard Silberstein could easily be by Klee:

Klee had an aquarium, and kept it stocked with tropical fish. When he invited Bauhaus students to his studio, first in Weimar and then in Dessau, they might have expected to see his latest art, but instead he positioned them in front of the fish tank, periodically using a stick in order, ever so gently, to get the specimens hogging the foreground to move so that hidden ones could be seen. He reveled in that underwater world.

I hope you don’t consider it too obvious when I point out that what preoccupied Freud when he was twenty is the same issue that concerned him forever after, and reached an apogee when he saw and later remembered Luca Signorelli’s frescoes: the degree to which a guy has balls.