|

Understanding Your Family’s Digital HabitatCultivating Online Resilience and Digital Citizenship |

|

Understanding Your Family’s Digital HabitatCultivating Online Resilience and Digital Citizenship |

Lori was the first of my “mom friends” to respond to my request for help. I had e-mailed several moms whom I respect to get their thoughts, worries, and ideas about raising kids in the digital era. Lori is an Ivy League–educated woman who had left her high-powered law firm to be a full-time stay-at-home mother after the birth of her second child, Madeline. She takes her job thoughtfully and seriously.

Lori sent me a three-page (no joke) e-mail on the evils of technology. She explained that her children preferred beautifully illustrated hardcover storybooks and played old-fashioned board games. Madeline is 5, and Jake is 7. She tries to limit their technology as much as possible. While writing this long e-mail, she received a delivery for her 2013 Christmas cards. She opened the box and, much to her dismay, realized that her daughter was holding an iPad in their perfectly posed family portrait.

She was completely aghast. She had defined her family culture by its lack of devices and technology, yet the iPad was front and center and in front of the Christmas tree. Lori is a very funny and self-aware mother, and the irony was not lost on her. She told me to dismiss the three-page e-mail on the evils of technology. It was time, she said, to face the reality that digital technology was fully integrated into her family’s life.

She sent back the cards to the company and had the iPad “Photoshopped” out of the picture, but she also began to reassess her dogmatic approach to digital technology. Lori lamented to me that her strict rules had blinded her to the fact that her husband and children were fascinated and intrigued by the innovations of digital technology. Lori took her blinders off and realized that it wasn’t only her children who were preoccupied with technology. The evening after the Christmas card fiasco, she was looking for her husband to discuss the new holiday cards. She opened the bathroom door to find her husband, a powerful Wall Street investment banker, curled up in a corner, engrossed in the über-popular game Clash of Clans. She asked him what he was doing, and he explained that he was hiding from the kids (and her) so they wouldn’t see him playing the game. Both Lori and I agreed that you can run, but you can’t hide, from technology.

Lori, like most parents, is seeking to strike a balance between the “human” and the “virtual.” In the 21st century, understanding your family’s digital habitat is a critical component to successful parenting.

We all want our children to be happy, successful, and safe. How do we reach this goal? We cannot shield our children from risk (either offline or online) or naively believe that education and knowledge acquisition are the one sure path. It’s not rules and restrictions that lead to success and happiness. Adversity is inevitable, and children need to be able to manage it. The cornerstones of adult happiness and success are, it seems, childhood resilience and character. Upon these cornerstones, good citizenship is built, digital and otherwise. As a psychiatrist, researcher, and mother, I believe that resilience is integral to developing character and citizenship and finding success and happiness both online and offline.

In his 2009 article “The Science of Success,” David Dobbs described what he called dandelion and orchid children. Dandelion children are healthy, or “normal,” children with “resilient” genes. They will thrive anywhere, whether it is the metaphorical sidewalk crack or the well-tended garden. In contrast, orchid children will wilt if ignored or maltreated but bloom spectacularly with greenhouse care.1

I agree that “resilient genes” play a role in children’s ability to manage adversity, but both research and human experience have found that parenting and love can change the course laid out by your genes. Our first digital parenting goal, therefore, is to cultivate online resilience and digital citizenship.

Resilient children turn negative emotions and experiences into positive ones. They successfully navigate adverse situations online not by avoiding them but by being exposed to risk. Overly restrictive parents are less likely to allow for the online mistakes and missteps that are critical to the development of resilience. Online resilience is the foundation for your children’s ongoing relationship with technology in every arena, from how to properly use various media platforms to adhering to the tenets of digital citizenship. Children with high levels of self-esteem and confidence are more likely to develop online resilience, while children with more psychological challenges will have more difficulty.2 (Chapter 11 offers some help to parents whose children have challenges pertinent to digital technology use.)

When I was trying to outline the components of online resilience, I came across Paul Tough’s How Children Succeed. He eschews the idea that intelligence and high SAT scores lead to success in life. He argues that the qualities that matter most have more to do with character: skills like perseverance, curiosity, conscientiousness, optimism, and self-control.3 Economists call these “noncognitive skills”; psychologists call it “character,” and I will refer to these traits in relation to the digital world as online resilience and digital citizenship. I believe that since your kids will spend more time in the digital world than eating, sleeping, hanging out, or going to school, they need more than real-life resilience. They need online resilience to care for themselves and digital citizenship to care for the world around them.

You can run, but you can’t hide, from digital technology.

Digital citizenship is the most important cyber term that you need to know. Digital citizenship reflects the norms and ethics of responsible and appropriate technology use. For me the term reflects qualities such as kindness, responsibility, conscientiousness, self-control, mindfulness, and altruism. I imagine schoolchildren reciting a pledge like the following after the Pledge of Allegiance:

Our children need online resilience to take care of themselves and digital citizenship to take care of the world around them.

THE PLEDGE OF THE DIGITAL CITIZEN

I pledge my commitment to upholding the values of digital citizenship. I pledge to take care of my self, others, and my community. I pledge to be mindful and thoughtful of what I say and post online. I pledge to use technology as a tool to improve both myself and my community. I pledge to use the power of the Internet and social media to spread kindness and philanthropy around the world. I pledge to uphold the digital golden rule to “do unto others as I would want them to do unto me.”

Digital citizenship has become a tool that schools use to prepare kids for the world of technology. In the United States, there is a national mandate to provide “advanced telecommunication services and information services” to public schools. Digital citizenship is loosely part of the Common Core curriculum. There is no required lesson plan. However, if a school or school district applies for additional funding for technology (called an E-rate grant), it must show proof that it is teaching digital citizenship in its classrooms.4

Digital citizenship seems like an obvious positive. There shouldn’t be too much to debate. Yet there is a whole literacy genre that includes op-eds, blogs, and books such as Distracted and The Dumbest Generation that fear technology will usher in a dark age for thought, creativity, and relationships. Many of the most popular movies (e.g., The Matrix, The Terminator) foretell a dystopian doomsday of brain-dead people controlled by computers. Are we headed into a Brave New World where 1984 comes true in 2015? Obviously I can’t answer that question, but the increasing power of technology companies needs to be monitored. So what can we do about it?

We can raise kids who understand digital citizenship . . .

We can raise children who can ethically manage Facebook or YouTube or whatever comes next.

We can raise children who can ethically manage Facebook or YouTube or whatever comes next.

We can raise children who are responsible and savvy users.

We can raise children who are responsible and savvy users.

We can raise politicians who understand the need for separation of powers and separation of technology and state.

We can raise politicians who understand the need for separation of powers and separation of technology and state.

Some examples of how you can promote online resilience and digital citizenship can be found in the next box.

![]()

Examples of Ways to Promote Online Resilience

• Talk to your kids about both “good” and “bad” TV.

• Help them to distinguish fantasy from reality on TV, Internet, and social media.

• Challenge the stereotypes they see online and on TV.

• Talking to them about the violence—asking them how the characters might feel.

• Teach them to be critical of advertising images and messages.

• Help them become critical consumers.

• Help them to assess the credibility and authenticity of websites.

• Following them on social media sites.

• Comment in person (not online) about poor choices they or others have made on social media.

• Turn small mistakes online into teachable moments, not punishments.

• Encourage them to apologize for or correct online mistakes.

• Keep open communication, so your kids can talk to you about online mistakes and concerns.

The journey starts at home. It starts with understanding your family culture and your family’s digital habitat.

You want your children to be prepared to head into cyberspace without a babysitter.

BOXERS OR BRIEFS?: DEFINING YOUR FAMILY CULTURE

To create a parenting blueprint that cultivates online resilience and digital citizenship, we must start with an examination of your family culture. Family culture is important because it will drive your family’s decisions about technology. It will help you understand and explain your approach to yourselves and to your children. Your family culture consists of who you are as a family inside and outside your broader community. Your ethnicity, religion, education, political views, and values shape your family culture. Each family is different and can’t be easily categorized as conservative, liberal, religious, or secular. It is the funny, subtle things that help to define your culture. For instance, what do you call your grandmother? Grandma, Grams, Mamey, Nana, Nonni, Ona, Bubbie, Mum, Mema? Here are some broader questions to get you thinking about your particular family culture.

What are your family traditions?

What are your family traditions?

How do you relax?

How do you relax?

How does your ethnicity and family background affect your family life?

How does your ethnicity and family background affect your family life?

How does your religion affect your family life?

How does your religion affect your family life?

How is your family the same as or different from your childhood family?

How is your family the same as or different from your childhood family?

What are your goals and priorities for your children?

What are your goals and priorities for your children?

Your family culture will determine the values that you apply to digital technology. Some families are primed to embrace technology and use it as a tool. Some will be more fearful and distrustful and will treat it as the “enemy.” Others will have mixed attitudes. Lori distrusted technology and tried to restrict it, but her husband and children coveted and embraced it. Your family culture should not be driven by technology, but should integrate it in a way that is fun, healthy, and enriching.

In this chapter we explore three elements of family culture that are critical to understanding your family’s digital habitat and composing your family technology plan:

You and your partner’s relationship with technology

You and your partner’s relationship with technology

Your parenting identity and style

Your parenting identity and style

Your family media consumption category

Your family media consumption category

Digital technology should be integrated into your family culture in a fun, healthy, and enriching way.

Your Relationship with Technology

Your relationship with technology is a critical part of your family culture. So where do you fit on the technology spectrum? Are you a tech-savvy grown-up? Are you the first to get the upgrade? Do you spend hours figuring out your new gadget, or would you prefer that someone else do it for you? There are no right and wrong answers, but you do need to understand your relationship with technology before you can guide your children. The baby boomers and Generation Xers have been labeled digital immigrants. Cyberspace and digital technology are a second language. Children and young adults born since the technology revolution are called digital natives. They speak digital without an accent. Here are some family culture questions for digital immigrant parents to better understand your relationship with technology.

What was your first memory of video games? E-mail? Social media?

What was your first memory of video games? E-mail? Social media?

Do you embrace or avoid the newest gadget?

Do you embrace or avoid the newest gadget?

How many TVs do you have in your home?

How many TVs do you have in your home?

Would you consider yourself a heavy, moderate, or light user?

Would you consider yourself a heavy, moderate, or light user?

Do you read the New York Times or play Bejeweled when bored?

Do you read the New York Times or play Bejeweled when bored?

On a “date” with your spouse, do you go to the movies or the gym?

On a “date” with your spouse, do you go to the movies or the gym?

Do you take your phone to the bathroom?

Do you take your phone to the bathroom?

Do you prefer reading on an e-reader or paper?

Do you prefer reading on an e-reader or paper?

Are you afraid of or excited about your children’s digital journey?

Are you afraid of or excited about your children’s digital journey?

Do you use the Internet regularly or occasionally?

Do you use the Internet regularly or occasionally?

Are you on Facebook?

Are you on Facebook?

Did you meet your spouse online? Did you ever date online?

Did you meet your spouse online? Did you ever date online?

Do you prefer to text or talk?

Do you prefer to text or talk?

Does your job require you to be constantly plugged in?

Does your job require you to be constantly plugged in?

Would you consider yourself a healthy digital role model for your children?

Would you consider yourself a healthy digital role model for your children?

Depending on your family culture, you may choose to write, e-mail, text, or keep in your head a list of qualities that define your family. Your list will help you determine whether you embrace, avoid, restrict, or permit.

Coming Clean: Who Are You as a Parent?

Once you have described your family, it is time to reflect on who you are as a parent. When we think about our identity as “Mom” or “Dad,” we often describe ourselves in reference to our own parents. Your own memories, regrets, and experiences as children heavily shape who you would like to be as a parent. It doesn’t mean that you will turn into your mother or father, but you can’t escape them. Whether you realized it or not, the birth of your first child likely triggered your own childhood memories. For the first time in years, you might have found yourself asking how your mother would have handled a situation. Perhaps you didn’t give your parents enough credit for their efforts. On the other hand, you may choose to do things quite differently than your parents. For example, you may be strict and limit technology because you perceive that your parents were not “strict enough.” For better or worse, your childhood memories and relationship with your parents will heavily determine your parenting identity and choices.

Here is a list of questions to help fine-tune your parental identity:

1. What were your parents’ biggest strengths and weaknesses?

2. What influenced your parents’ ability to parent? (e.g., divorce, illness, mental health, substance abuse)

3. How did your parents treat your siblings differently?

4. Did your parents have lots of rules and expectations?

5. How did your parents punish you when you did something wrong?

6. Do you have role models for parenting other than your own parents?

7. How would you like to parent similarly and differently than your parents?

These questions are designed to help you formulate a picture of who you are as a parent and where it came from. Questions 1–3 should help you understand your own parents from your current adult vantage point. When trying to decide how to handle digital technology or any other major ingredient in your child’s life, it’s helpful to know where you might struggle. Those parents who face the most parenting challenges often had an ambivalent or disappointing relationship with their own parents. If this is true for you, then it is important to understand where and how you feel that your parents failed you. You can use their failures to your advantage as you parent your own children in the real and virtual world.

Questions 4 and 5 should paint a picture of your parents’ parenting style. If your parents encouraged independence while setting clear expectations, you may feel comfortable giving your children developmentally appropriate freedom to explore and embrace technology. If your parents were critical and demanding, then you may find yourself being generally fearful and restrictive in your parenting. With each real and digital milestone that your child achieves, you may “remember” different things about your childhood and your parents. You may remember your own fear about leaving for summer camp or your own humiliation about disappointing your parents in some way. You should take stock of these memories and moments. If you recall humiliations or disappointments from your own childhood, pay attention. It is these memories and unresolved experiences that may hamper or impact your present-day parental decisions. If you feel like you have mishandled decisions as a parent, think back to your childhood and your own parents for an answer or solution. Be conscious of your sticky memories as a child so you can be mindful in supporting and guiding your own children in a different direction.

The last two questions allow you the opportunity to think forward about how you will use your childhood experiences to positively shape your parenting style. We may not have control over our own childhood experiences, but we can use them to make better parenting decisions for ourselves and our families.

Curfews or Candy?: Defining Your Parenting Style

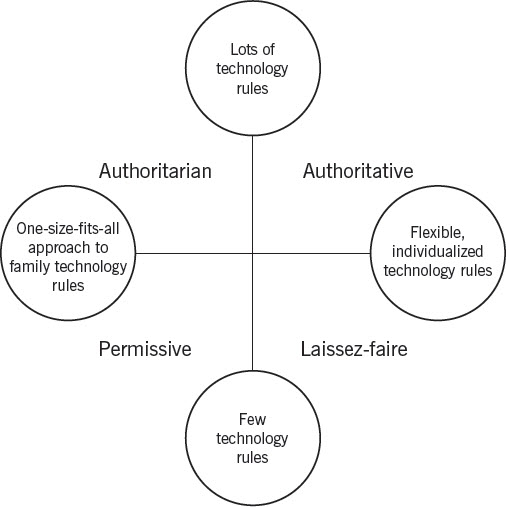

There is emerging research showing that parenting styles affect your children’s media use and their online resilience. Generally, researchers divide parenting styles into four categories: authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, and uninvolved or laissez-faire. More recently, researchers have applied these four categories to digital technology and refer to them as Internet parenting styles. Your general parenting style will undoubtedly be reflected in how you approach and manage technology. Parental warmth and parental control are the two components that mediate digital parenting styles.

Parental warmth or responsiveness refers to intentionally fostering individuality and self-regulation. It describes the level to which a parent accommodates and cultivates a child’s individual needs.

A parent with high parental warmth would be more likely to engage children in developing technology rules.

A parent with high parental warmth would be more likely to engage children in developing technology rules.

Parents and children would be more likely to share technology experiences.

Parents and children would be more likely to share technology experiences.

Children would be more likely to share upsetting or shocking online experiences with their parents.

Children would be more likely to share upsetting or shocking online experiences with their parents.

Parental control is linked to restrictions about technology use and clear guidelines about acceptable content.

Parents with high parental control are more likely to personally supervise or use parental controls and filters to monitor Internet use.

Parents with high parental control are more likely to personally supervise or use parental controls and filters to monitor Internet use.

A parent with high parental control might set non-negotiable technology restrictions.

A parent with high parental control might set non-negotiable technology restrictions.

Parents with high parental control would focus less on individual needs and more on consistent rules with reliable consequences.

Parents with high parental control would focus less on individual needs and more on consistent rules with reliable consequences.

Take this little quiz to find out more about your digital parenting style:

1. My approach to family rules for technology is:

a. I wouldn’t bother.

b. I would try my best to enforce rules but might have difficulty with follow-through.

c. I would include my children in the process of developing a family technology plan.

d. My husband and I will type up clear, consistent rules about when and how technology can be used.

2. Ideally, how would you monitor your child’s Internet use?

a. Wouldn’t bother.

b. Would occasionally look at my child’s phone or search history.

c. Would consistently check my child’s texts and quietly follow her on social media sites.

d. Would install parental controls and filters. I would block inappropriate websites and monitor all activity.

3. Would you allow your son to play online games on school nights?

a. Of course. What else would he be doing?

b. Yes. He needs the break, and hopefully he will get his homework done afterwards.

c. Yes. But he needs to complete his homework and show it to me, and then I am happy to let him play or to play a game with him.

d. No. Video games are addictive and distracting. He needs to focus on his homework, and he can play games on the weekend.

4. What would you do if you found your daughter sending an inappropriate photo to her boyfriend?

a. Nothing. It is her private business.

b. Express concern and discuss what is going on in the relationship.

c. Express concern about my daughter’s self-esteem while contacting the boy’s parents to make sure the picture is not forwarded. Then take away her phone for the next few days.

d. Forbid my daughter from ever seeing the boy again and then take away her phone for the next month.

From Screen-Smart Parenting. Copyright 2015 by The Guilford Press.

If you circled a for many questions, then you may fit into the laissez-faire or uninvolved parenting style. This style is self-explanatory, and it is unlikely that laissez-faire parents are reading this book. Laissez-faire parenting is linked to poor self-esteem and less resilience in children. It is also the least common style of parenting.

If you answered b to two or more of these questions, then you likely fall into the permissive parenting category. Permissive parents often have a high level of responsiveness or warmth and a low level of restriction. They care about the unique needs of their child and tolerate immaturity and dysregulation. They may recognize the need for technology rules but are less likely to implement them or be consistent with consequences.

If you answered d to two or more questions, then you would be described as authoritarian. Authoritarian parents have rules that are not to be questioned. These parents often provide consistent technology rules and consequences. However, they often do not consider each child’s individual desires and needs. Consequently, they achieve behavioral control, but the rules are not always internalized and generalized. They try to instill their family’s values and expectations about technology by decree and not through discussion. Permissive and authoritarian styles reflect the two ends of the healthy continuum for parental warmth and control.

Two or more c answers reflect an authoritative style. Authoritative parenting is the most commonly reported style and the style most closely associated with building online resilience and digital citizenship. Here is an example of a teenage girl describing her authoritative parents.

“My mom won’t buy me the new iPhone yet. She says that my current iPhone is just fine and that I should question who my friends are if they judge me on the model of my phone. I am allowed to watch TV and post on Instagram during the week, but I have to do all of my homework first and show it to my parents before I am allowed to get on the Internet or watch videos on Hulu. My mom insists on following me on Instagram and friending me on Facebook. It is a bit weird, but she helped me manage this bullying thing that I got involved in. She made me write an apology letter and forced me to call the girl. It actually turned out okay, and I am much more careful online now.

“I am allowed to go out with my friends, but I have an 11:00 P.M. curfew and have to text my mom when I change locations. She has to talk to the mother of where I am spending the night, which is totally annoying, and overkill. I had a boyfriend, but he was acting like a jerk. I broke up with him, and my mom was pretty cool about the whole thing and said that I used good judgment and might be ready for an iPhone upgrade at Christmas.”

Authoritative parents strike a balance between warmth and control. They demand adherence to a code of conduct, but consequences for violations are more supportive and less punitive. They do see their children as individuals and accommodate their needs but expect their children to be socially responsible as well. Authoritative parenting has been associated with positive outcomes among adolescents in psychological and cognitive development, mental health, self-esteem, academic performance, self-reliance, and greater socialization.5

Permissive and authoritarian parents need to recognize the digital pitfalls in their parenting approach. In an effort to support and promote independence, a permissive parent stands the risk of not setting the expectations and guidelines needed for healthy development. Authoritarian parents manage and monitor well but stand the risk that their children will not be prepared to manage technology on their own. A balance between warmth and control leads to authoritative parenting. I have modified a diagram from Martin Valcke’s study on Internet parenting style to give you a visual of the interaction between parenting styles—see below. Authoritative parents are best positioned to promote online resilience and subsequent digital citizenship.

Authoritative parents are best positioned to promote online resilience.

Parenting styles and Internet control. Based on Valcke et al.6

Candidly Assess Your Family’s Technology Diet

Usage, usage, usage. The millions of statistics about digital technology generally relate to usage. Permissive and laissez-faire parents allow more use of technology. Authoritarian parents allow less. But what else drives the quantity and content of technology usage within an individual family?

There is a general notion that children drive the consumption and type of media use in a family, but how could babies and young children create the media environment in their homes? The answer is that they don’t. In 2013, the Northwestern Center on Media and Development published an impressive study on parenting in the age of digital technology. They surveyed 2,300 parents of children from birth to 8 years of age. They also conducted several focus groups in California and Illinois. This study is so interesting because it is one of the first to look at younger children. In this book, I divide the statistics on usage into two groups: usage by children 8 years of age and under, and by those 9 years and over. The reason is pretty simple: Kids 8 and under often use technology with their parents and are more likely and willing to play educational games and apps. At age 9 or 10, children become literate, social, and independent. There is less media co-engagement, and the conflict begins.

The researchers at Northwestern found that parents of young children were creating different types of media environments. The study identified three different parenting styles: media-centric, media-moderate, and media-light families.7

Reading the descriptions below, which group do you think you fall into?

Media-centric parents: This group accounted for 39% of the participating parents. These parents love using media and spend an average of 11 hours per day on it, including more than 4 hours a day of watching TV, 3½ hours per day using the home computer, and 2 hours on their smartphones. These parents tend to keep the TV on at home most of the time even if no one is watching. Nearly half (44%) have TVs in their children’s bedrooms. These parents use TV and media to connect with their kids. Although they do watch TV with their children, more than 80% of these parents report that they use TV to occupy their child when they need to make dinner or do chores. Their children spend on average 4½ hours per day on screen media. These children spend 3 hours more per day on media than children of “media-light” parents.

Media-moderate: This was the largest group, accounting for 45% of parents surveyed. These parents spend approximately 4½ hours on screen media at home. The parents play limited video games. While they like watching TV, they are less likely to list watching TV and movies as a favorite family activity. They tend to prioritize doing things as a family outside more than the media-centric families. Children in media-moderate families spend approximately 3 hours per day with screen media.

Media-light: Only 16% of families were classified as media-light. These parents spend fewer than 2 hours per day with screen media. They are much less likely to put TVs in their children’s bedrooms. They are less likely to report TV and movies as a fun family activity and less likely to use TV and media to occupy their kids. Children in media-light families spend on average 1 hour, 35 minutes a day on screen media.

It is the parents’ relationship with and consumption of digital technology that shapes their children’s usage in the home. Parents use technology with younger children in a way that is cooperative, creative, and moderate. Technology is not a point of conflict in families with young children. Parents jointly participate in young children’s media experience. They may enjoy watching a show or playing a game together, but they also prioritize and value the time they spend with their children offline.

The statistics look quite different for 8- to 18-year-olds. The Kaiser Foundation has tracked media use since 1999. In 2009, they surveyed 2,000 kids and had 700 kids keep detailed media diaries. They found that the average 8- to 18-year-old spent 7¾ hours per day using digital technology and 10¾ hours if you count using multiple devices at one time.8 Daily use totaling 10¾ hours is mind-boggling, but what is more shocking is the increase in national usage in the 5 years from 2004 to 2009.

By 2009 kids were spending 2¼ hours more time on digital technology than they did in 2004:

• 47-minute increase in music/audio.

• 38-minute increase in TV.

• 27-minute increase in computer use.

• 24-minute increase in video games.

• No change in movies or print.

At this rate, by 2019 kids will be spending over 15 hours per day on digital media! There would be no time left to eat, sleep, or see real people. You may be reading these stats and saying there is no way your children consume that much media.

Are you sure?

I am challenging you to find out how much media you and your children really use. If you visited a nutritionist to lose weight, you would be told that you need to understand and track your eating habits before going on a diet. As with eating, technology use is best in moderation; as with counting calories, it’s hard to be honest about how much time you spend on technology. Here are some pointers to keep yourself honest:

Try to keep a media diary for each member of your family for 3 days. If this exercise sounds overwhelming, then monitor each family member individually. It would be best if your children who are older than 8 years kept their own diary. I have not yet found the perfect media diary app for tracking multiple people over multiple online and offline devices. RescueTime monitors the details of Internet usages and sends you weekly graphs. TimeRabbit measures how much time you lose down the proverbial “rabbit hole” while on social media. I am not recommending that you use the parental monitoring programs for this purpose, but there is a variety of tracking software out there. Right now, we are simply doing a 3-day experiment to document how much time is spent each day on

TV: real time, delayed, and Web-based

TV: real time, delayed, and Web-based

Computer/tablet: online and offline activities (include homework, but star it)

Computer/tablet: online and offline activities (include homework, but star it)

Phone: includes voice calls, texts, games, and surfing

Phone: includes voice calls, texts, games, and surfing

Gaming consoles: handheld and stationary

Gaming consoles: handheld and stationary

While all TV time should be included, I would not include music at this time unless your family is listening to music while surfing the Internet or playing a game. “Multitasking” counts more than single-tasking. If possible, highlight or underline when multitasking occurs. We are not trying to sweat the details. We want a general idea of how much time each member of your family spends with technology.

Here are my suggestions for keeping an accurate record:

Track hourly (not daily or weekly). If you can’t do 3 days in a row, then pick a few days in a week. Be sure to include a weekend day and a weekday.

Track hourly (not daily or weekly). If you can’t do 3 days in a row, then pick a few days in a week. Be sure to include a weekend day and a weekday.

Send yourself a text or put a note in your calendar each time you use technology. You can also keep a paper notebook with you.

Send yourself a text or put a note in your calendar each time you use technology. You can also keep a paper notebook with you.

Consider sending text reminders to older members of your family throughout the day to remind them.

Consider sending text reminders to older members of your family throughout the day to remind them.

If you are concerned that your teenager won’t be reliable, then have her send you a text message with each usage so you can track it.

If you are concerned that your teenager won’t be reliable, then have her send you a text message with each usage so you can track it.

If needed, you can look at phone usage data or utilize RescueTime for online activities.

If needed, you can look at phone usage data or utilize RescueTime for online activities.

Be honest.

Be honest.

After collecting the data, you can take an honest look at how your family uses technology. Look for problematic patterns such as late-night Internet use or extended texting during homework time. Learning how to “shut down” at night is challenging, and you may choose to get more involved in the sleep-time ritual or to turn off the Internet in your home at a certain time. In Chapter 11, I examine problematic Internet usage and help you determine whether your child is at risk. For now, we are trying to get an understanding of your family’s digital habitat.

The results of your media diaries might surprise you. Usually, parents are more surprised about their usage and patterns than those of their children. Children learn by example. We all know that if Mom and Dad are texting and checking Facebook throughout dinner, then it is hardly shocking that the kids will follow suit. One of the tricks of the child psychiatry trade is knowng that parents’ behavior heavily influences children’s behavior, especially when kids are 12 and younger. It is quite common, for example, for an anxious 8-year-old to be referred to me. No one understands why this youngster is so anxious. I meet the parents, and it is obvious that one or both of them are extremely anxious. I will tell the parents that we need some extra parenting sessions before I meet extensively with the child. I will try to address the parents’ anxiety. Sometimes I will refer the parents for their own treatment. Presto! The child’s anxiety gets better. The same is true for bad media habits.

THE SECRET TO SUCCESSFUL DIGITAL PARENTING

At this point, you hopefully can accurately decorate your family’s digital habitat. You can decorate the master bedroom (parents’ use), the children’s bedroom (children’s use), the basement (children’s hidden and unrecognized usage), and where it all comes together in the family room (family’s approach to technology in general). The goal is to strive for authoritative parenting that combines both parental warmth and parental control. Your technology relationship and patterns will drive how and when your children use digital technology. If you are able to embrace innovation and co-engage with your child, you are likely to cultivate both online resilience and digital citizenship.

Your family’s digital habitat will provide the soil for resilience and citizenship to bloom. It is your family’s ongoing dialogue about digital technology that will provide the water and sunlight that your children need to prepare them for the challenges of the digital era. Your fears and ambivalences will be betrayed in these dialogues. It is essential to recognize your own concerns, but not to transmit them. Of course, you want to protect your children from the risks and pitfalls of technology. The goal is to empower your children to be critical consumers and not helpless victims. For instance, talking about TV shows and commercials can help them distinguish fantasy from reality, confront stereotypes, and lessen the effects of violence. Using the Internet together can help your children develop the subtle skills needed to ignore a mean comment or choose a positive social media site or game.

Hopefully, this chapter has helped you understand your parental identity and the context in which you function as a parent. It should be obvious by now that you must be honest and self-reflective in order to cultivate the resilience your children need to grow up in the digital era. In the last chapter of this book, you’ll have a chance to create your own family technology plan based on your understanding of your family culture, in addition to everything you’ll learn in the rest of this book about how digital technology can be used as a tool to support your child’s growth into a resilient digital citizen.

Everything that follows in Screen-Smart Parenting is based on a developmental model of digital parenting. Most thoughtful approaches to parenting take into account the physical, cognitive, social, and emotional components of child development, and parenting in the digital world should be no exception.

Your children will inevitably achieve digital milestones like getting a phone, joining a social media site, or e-mailing homework to a teacher. Like developmental milestones, such as walking and talking, they come whether you are ready or not. The difference with digital milestones is that parents have some say in when and how they unfold. I promise you that they will unfold eventually, so it is better to develop a plan and not leave it to chance and cyberspace.

Digital milestones come whether you are ready or not.