NEVILLE WILLIAM

CAYLEY

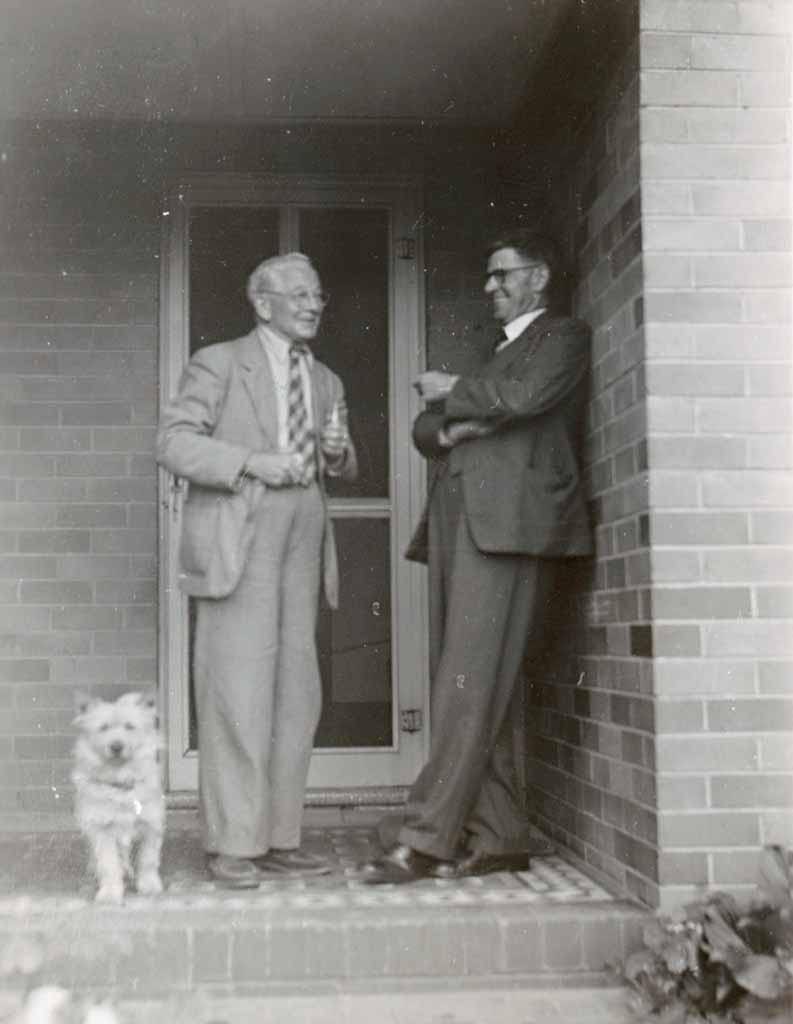

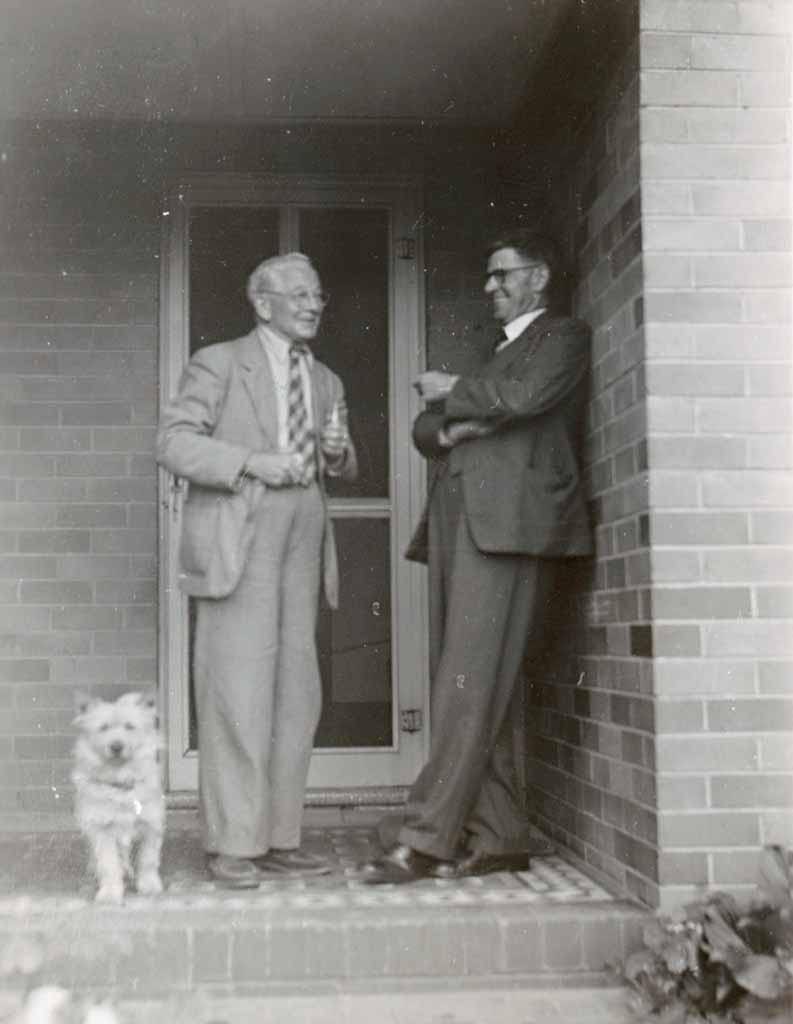

Portrait of Neville Cayley c. 1936

In 1936, Cayley was elected President of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union and this photograph, published in the organisation’s journal, Emu, accompanied the minutes of the 1937 Annual General Meeting, at which he did not stand for President again.

The inheritor of the Cayley name and mantle, Neville William Cayley, was a January baby, born in Yamba on the north coast of New South Wales in 1886. The family moved to and from Sydney several times during Cayley junior’s childhood, living in various picturesque country towns, with the result that he attended several local public schools. In 1898, they settled in the Sydney suburb of Waverley. Cayley turned 12 that year and it is possible that his parents wanted him to have stable secondary schooling. At 17, he lost his father to Bright’s disease. How the family coped can only be surmised. Certainly, art dealer William Aldenhoven, Cayley senior’s friend and sole agent for 16 years, continued to sell his original work for another 20 years. Cayley’s popular and well-coloured cards—including postcards, first produced by the New South Wales Bookstall Company in about 1904 and reprinted several times—were marketed across Australia and would have brought in royalties.

Neville William Cayley got his first job around the age of 17, painting go-carts for 15 shillings a week, working all day from 8 am. It soon became tedious. His father had put a brush in his hand at an early age but it was not until after his father’s death that he began to sketch seriously, during a recuperation lasting several months following a football injury to his leg. Prolonged home rest was then standard for broken limbs. Subsequently, Aldenhoven exhibited his paintings of birds alongside his father’s in 1905, when Cayley was 19. The younger Cayley had inherited his father’s love of nature and his first ornithological works were derivative if not imitative, much like his father’s in every way (see page 108), although without the technique. From the start Cayley distinguished himself from his father by signing as ‘Neville W. Cayley’ or ‘N.W. Cayley’.

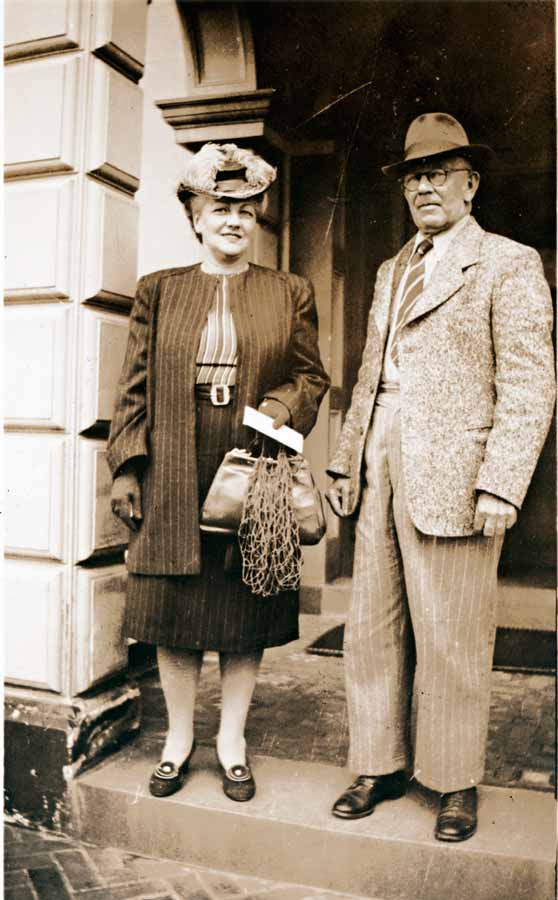

Neville William Cayley with his sisters Alice (in front) and Doris c. 1896

This photograph was possibly taken after the itinerant family returned to Sydney in 1895, when Cayley would have been ten years old.

By 1906, 20-year-old Cayley had another passion—for the sea. He was one of the ‘Waverley Cavemen’ who found freedom at Cronulla, away from the more northern beaches with their restrictive dress and bathing regulations. On weekends and holidays, they set up a temporary ‘clubhouse’ in the cave at the southern end of the beach. The trip from Waverley—by train to Sutherland and then by Mrs Giddings’ horse and coach to Cronulla— took most of the day. If Mrs Giddings’ coach was not available there were plenty of other three- to five-horse coaches touting for business. The coachmen often added to the fun, racing each other to the beach.

Cayley was among the enthusiasts who founded the Cronulla Surf Club. He became its first secretary in 1907 and filled that role again in 1908. The club, perhaps the first in New South Wales, quickly became a social centre. It held popular sports days. At Easter 1908 a crowd of 2,000 headed to the beach to watch the fancy dress competition, pillow-fights (on a slippery rail), footraces and wrestling. Cayley’s team was a regular winner of the tug-of-war event. At the third annual carnival in March 1910, a fit 24 year old, Cayley won the ‘carry your chum’ race and the scratch footrace. As other clubs took off so too did interclub competitions.

There was also a serious side. The surf club organised an informal lifesaving service. Indeed in February 1914 Cayley was part of a crew on duty who battled big seas to rescue five men and two girls washed out to sea.

It was a time of great change in terms of beach culture. In 1907 Surf Life Saving New South Wales led protests that helped minimise the clothing requirements on beaches, however bathers still had to be covered from neck to knee. A constable was appointed to maintain decorum, but he had little luck. He would ride his bike from Kogarah. However, from a secluded place in the sandhills, the bathers kept an eye out for his tall hat and by the time he had struggled—in full uniform—over the sand, they had covered up. When he had passed, they rolled down their tops or sunbaked nude, and shot the waves.

Early in 1907 the constable was moved to Cronulla and given a horse, but the authorities were beginning to face reality. By the end of the year, while other beaches were still restricting surf bathers, Cayley and his colleagues had convinced Sutherland Council to consider installing bathing sheds and a water supply.

At this time Cayley was living at Cronulla. Later, according to the Sands’ Sydney Directory, his mother, Mrs L. Cayley, ran a boarding house from 1912.

Surf Bathing, Manly Beach, New South Wales 1900

Cayley was a dedicated member of the ‘Waverley Cavemen’, who travelled to Cronulla Beach at every opportunity to surf and sunbathe. At Cronulla, there was less risk that strict Council dress and behaviour codes would be enforced, in contrast to northern Sydney beaches such as Manly (pictured).

Duke Kahanamoku with His Famed Surfboard on Cronulla Beach, February, 1915

Cayley was a keen surfer and sunbather, regarded as somewhat scandalous activities at the time. In 1907, he was a founding member of the Cronulla Surf Club and later became a pioneer of the Surf Life Saving movement. When Duke Kahanamoku (at left) visited Australia with his revolutionary surfboard, Cayley (fifth from left) was among the excited bodysurfers who welcomed him to Cronulla.

Surfing was not the only thing on Cayley’s mind and from about 1918 he often took a trunk of reference bird skins home from the Australian Museum to help him finish his paintings. His method was to draw the picture quite thoroughly first before painting over it.

The clubhouse cave became two tents, then two tramcars placed end to end. Cayley lobbied for a shed for the club: not just a changing-shed, but a centre for the humanitarian service that had to be provided for the rapidly increasing numbers of swimmers and surf bathers. In 1914, as surf lifesaving became more professional, Cayley was among the first batch of certified instructors.

Early the next year, 1915, Duke Kahanamoku, the famed Olympic swimmer and surfboard rider from Hawaii visited Australia, receiving much publicity and raising interest in boarding. However, it was wartime and many young men were called away, some never to return. Cayley helped to keep the surf club going and in 1918, post war, he actively revived interest by visiting the local high school and offering to train the students in rescue and resuscitation, inspiring some to join as lifesavers. The next year he proposed the formation of a swimming club at Cronulla, which, together with the Cronulla Life Saving Club (renamed in about 1921), still exists today.

Cayley was made a life member of the Cronulla club in 1920. He was their representative on Surf Life Saving New South Wales, and Vice-President until 1926. He also became a member of the executive of both the Surf Life Saving Association of Australia and the Royal Life Saving Society.

In the early days, Cayley’s oldest sister Alice enjoyed the athleticism and experience of the new beach life as much as Cayley did, and, with a small group of female friends, gave demonstrations of surf shooting at carnivals. However, by the 1930s, the clubs had become male dominated. It was decided that women were not suitable for beach patrols because they would not be heeded; instead, they were left to organise social events. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union of New South Wales weighed in, claiming that inclusion of female participants in carnivals was ‘lowering the dignity of women’.

Nevertheless, postwar consumerism was on the rise and more members of the public were enjoying the pleasures and freedoms of a day at the beach, with the accoutrements to match. Late in the 1930s neck-to-knee attire gave way to one-piece swimming suits for women and trunks for men. By then, Cayley had turned his considerable energies to birds and painting. Although he never totally lost ties with the surf lifesaving movement, the illustrative and ornithological pursuits that he had been exposed to as a child would almost inevitably come to the fore.

However, back in 1909, Cayley had not settled on a career path, but he was selling the occasional bird painting. That July he illustrated an article in The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser entitled The Tragedy of Mr and Mrs Jacky Winter: a moral tale involving a boy, a pearifle and a pair of nesting birds. This was possibly his first published artwork. He also contributed to that year’s Rowlandson’s Success: A Volume of Australian Literature, an annual published by the New South Wales Bookstall Company. Cayley provided some ‘wash’ illustrations, reproduced in black and white. They were sketches of patriotic kookaburras, two of which were full page: Night Out showed a top-hatted kookaburra clasping a bottle of beer in its feet, while in On Guard the bird sported a sailor’s cap and a scarf decorated with the Union Jack. The cap was emblazoned with the words ‘HMS Powerful’, one of the largest warships of the time and the flagship of the Royal Navy’s Australia Station. The United Kingdom was anticipating a possible war in Europe.

Neville William Cayley, The Tragedy of Mr and Mrs Jacky Winter 1909

Cayley’s first published work appears to have been the illustration of a moral tale based around a pair of Jacky Winters, published in a July 1909 edition of The Sydney Mail. The newspaper had also employed his father as an occasional illustrator of birds.

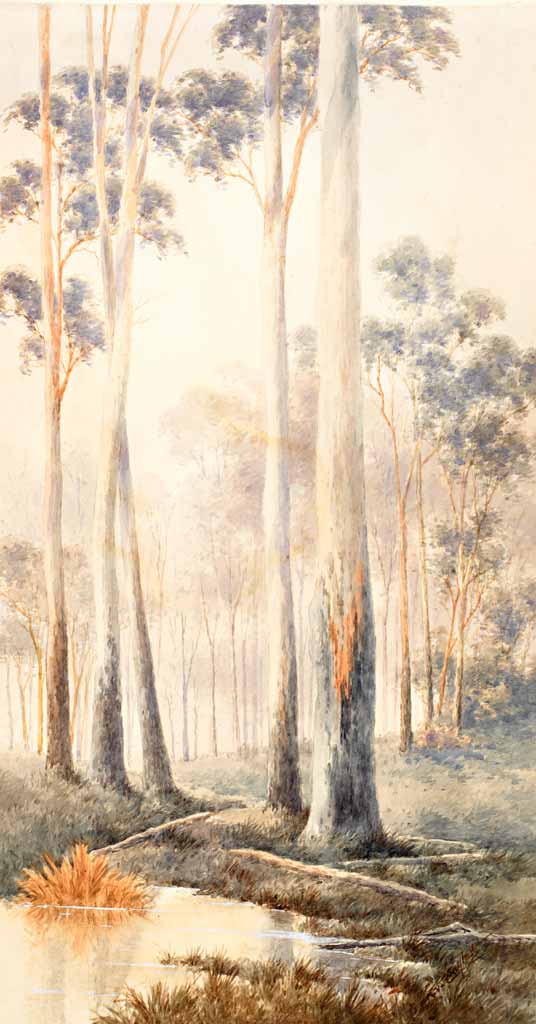

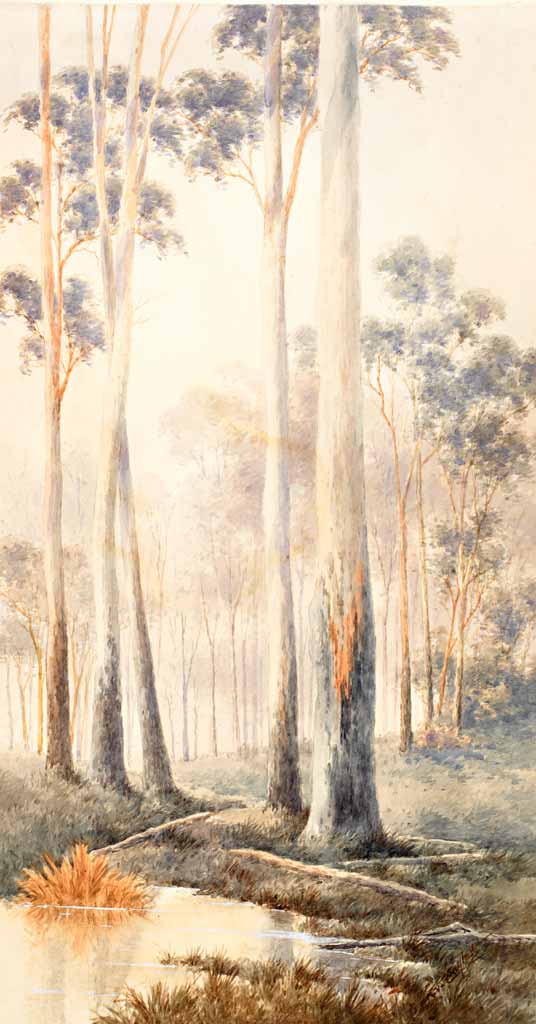

Neville William Cayley, Gum Trees

In the 1910s Cayley tried his hand as a landscape painter, producing pictures to hang on the walls of hotels and homes. It was not until the 1920s, when he was well into his thirties, that Cayley’s bird portraiture, particularly that produced for educational and scientific purposes, came to the fore.

Despite his keen interest in birds, Cayley was not yet wedded to them artistically. He attended art classes and joined a group of Sydney artists painting birds and landscapes as ‘furniture pictures’, that is, decorative works without pretension to fine art, for the walls of homes and hotels. Some of his landscapes are dated around 1916 and a botanical work, a ‘luscious collection of flannel flowers, waratahs, and wattles’, as reported in The Sydney Morning Herald, was painted in 1912. Such painting would bring Cayley a modest income, but it would be his love and knowledge of birds that would set his life’s path. His improved skills at landscape painting were never wasted though; they would later come to provide naturalistic settings for his depictions of birds.

Neville William Cayley, On Guard 1909

Neville William Cayley, Come and Join Us 1909

Cayley was invited to provide illustrations of kookaburras for Rowlandson’s Success: A Volume of Australian Literature, which came out in the second half of 1909. In one drawing, a black-and-white version of which appeared in the second volume of the publication, Mrs Kookaburra—complete with tambourine and a copy of War Cry—is ready to spruik for the Salvation Army, while in another a kookaburra sports a Union Jack and a sailor’s cap. The drawings reveal that Cayley had inherited something of his father’s sense of humour, and also his patriotism —war was brewing.

On 15 December 1917 at Marrickville, 31-year-old Cayley married Beatrice Lucy Doust. Beatrice was the daughter of Herbert and Minnie Doust of Dulwich Hill, who were possibly friends of the family. The kind, gentle Beatrice was about two-and-a-half years younger than Cayley and they had both lost their fathers as teenagers. Beatrice’s father, Herbert Doust, was a well-known stock and share broker. Facing financial troubles, in January 1900 he had shot himself with a revolver, leaving a wife and four children.

In 1918 the Aldenhoven Art Gallery published Cayley’s first booklet, Our Birds; the originals were displayed in the Hunter Street gallery. The ribbon-tied booklet was a modest start in the field that Cayley was to make his own and the display apparently was his first dedicated exhibition. The Minister for Education, Augustus James, who opened the show, averred that:

Neville William Cayley, Duck in Flight Being Shot 1907

Cayley’s early works were very similar to his father’s, but not as technically skilled. This dying Black Duck echoed Cayley senior’s first really successful and most popular image (see page 23).

Mr. Cayley possesses a fine art as a colourist, and a remarkably sympathetic style. His illustrations of bird life display much and varied charm as pictures, and his Blue Mountain landscapes will also be admired.

James took the opportunity to compare Cayley with his father, observing that ‘the original bird painter relied entirely and absolutely upon his exact definiteness of each species’, while ‘the younger man added an attractive wealth of detail to illustrate the habitat of the various feathered songsters’.

The Minister also used the occasion to push the cause for the protection of birds and their habitat by educating the young. As a Sydney Morning Herald reporter noted, James had expressed the view that:

It was much to be wished that property-owners in large cities would preserve, instead of destroying and replacing with foreign trees, the natural homes of the birds … [which are] only saved by such places as the National and Centennial parks … In his boyhood hunting the birds with a catapult was regarded as the right and proper thing to do; but with the aid of nature studies a change of opinion had been cultivated at the State schools, and it was surprising how much was known of the fauna and flora of the country.

The eight-leaf Our Birds featured seven popular species (a fairy-wren, robins, a finch, a honeyeater, a whistler and the Budgerigar), illustrated perched on a native plant and with a few lines on distribution, behaviour and habitat. It was followed shortly after by another little book—Our Flowers—one of Cayley’s few strictly botanical works. Released for Christmas 1918, Our Flowers contained seven illustrations of wildflowers with brief notes and a plea for the plants’ preservation by Mr G. Hamilton of the Sydney Teachers College. The modest publications were a tentative step towards Cayley’s later, more ambitious, educational projects.

Neville William Cayley, covers of Our Flowers (1918) and Our Birds (1918)

Even Cayley’s earliest publications, starting with Our Birds and Our Flowers in 1918, were aimed at educating the public about Australian birds and nature. They were small, attractive, coloured booklets, published by the man who had been his father’s agent, William Aldenhoven. While they look modest today, at the time there was little else to fill that niche.

Cayley was soon to suffer one of several losses in his personal life. In January 1919, his first child, a son, was stillborn. But the next year, things looked up. He and Beadie (Beatrice) were living at Granville, where she gave birth to their first surviving son, the third Neville Cayley. They named him Neville Clive Cayley.

Around that time Cayley was becoming more involved with the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union (RAOU). In October 1919 he had joined about 60 delegates at the annual congress in Brisbane, the first such get-together since 1914 and the First World War. As reported in the organisation’s journal, Emu, the dry conditions ensured a good collection of birds around the destination of the ‘Waterworks’. Cayley and his friends went off in pursuit of Lambert’s Blue Wren (Variegated Fairy-wren) and returned to the others ‘perspiring but happy’. They excitedly reported that they had found two pairs nesting close together and that Cayley had made an impression by ‘emitting the well-known chirp, [which] drew the mother to his hand to fearlessly feed her young’.

The delegates agreed that there was such a strong and growing interest in birds that the need for a comprehensive guide was becoming critical. They acknowledged that Gregory Mathews was part way into his costly 12-volume publication The Birds of Australia (1910–1927), but that what was lacking was a book accessible to everyone. Required too was a checklist—a list of all species in Australia with their common and scientific names. The meeting welcomed the news that Cayley had determined to produce a bird book— to be issued in 60 monthly parts and illustrated with hand-coloured plates. In turn, the RAOU determined to assist.

In October 1920 Cayley’s intended publisher, George Robertson of Angus & Robertson, Sydney, held an exhibition of some of the drawings for the imminent book, unimaginatively titled Birds of Australia. May Gibbs’ drawings for Little Ragged Blossom, and More about Snugglepot and Cuddlepie were also on show. The brainchild of Robertson, the bird book was to be edited by Albert Sherbourne Le Souëf, the first director of Sydney’s Taronga Park Zoo, and nature writer Charles Barrett, of Victoria. Cayley’s illustrations were a great selling point. The announcement in The Sydney Morning Herald promised that: ‘Many of these drawings are very beautiful, and will be appreciated even by people having no special degree of ornithological knowledge. The colouring is exquisite’. There were nine paintings of birds including ‘quails, flycatchers, finches’, as well as some ‘well executed’ eggs.

Bird lovers across the country greatly anticipated the much-needed publication. Cayley had also begun to supply illustrations for Emu. The first appeared in October 1920: a plate illustrating the Yellow-spotted Honeyeater and Lesser Yellow-spotted Honeyeater (now known as the Graceful Honeyeater) to accompany an article on birds of the Torres Strait Islands.

By October 1921 there was no sign of the much-anticipated book and questions were being asked. A Queensland newspaper, The Morning Bulletin, complained that ‘nothing definite can be elicited’ of the ‘long-promoted’ book. The reporter was an admirer of Cayley’s work and revealed the supposed reason for the delay in his wish that ‘the price of art paper would drop in a hurry so that the publishers could get to work’.

Angus & Robertson continued with their regular promotion of the imminent book. Cayley’s name became even more prominently associated with the project, even though there were many other contributors. Early in 1922, Donald Macdonald, journalist and nature writer for The Argus (Victoria) was calling it ‘Cayley’s Bird Book’, which, he wrote, the publishing house ‘have in hand for early issue’ in 60 parts. The publication would cover all that was known about Australian birds and their habits, unlike Mathews’ book, which was largely taxonomic in purpose. The illustrations would not be stiff depictions of skins from museum cabinets; rather, they promised to be lifelike, showing the birds in action and in appropriate habitat.

The next year, a Victorian, John Albert Leach, relieved the pressure somewhat with An Australian Bird Book: A Pocket Book for Field Use, the first field guide for the nation. It was snapped up by bird lovers and Leach added to it for a 1926 revision. Nonetheless, as welcome as it was, and despite the revised edition’s new subtitle A Complete Guide to the Identification of Australian Birds, Leach’s guide was concerned primarily with Victorian birds, a frustration for users in other states.

The year 1923 was an emotional one for Cayley, ending with two weddings and a funeral. In September, the Cayleys’ long-term agent and supporter William Aldenhoven died. The sensitive and entrepreneurial Aldenhoven had wholeheartedly represented the Cayleys since Neville junior’s birth in 1886. It was Aldenhoven who had put the Cayleys’ name on the map as Australia’s premier painters of birds.

In November, Cayley and a number of other birdmen travelled to Brisbane for the nuptials of ornithologist, author and Gould League supporter Alec Chisholm. A pair of lovebirds by Cayley decorated the reception menus. The two men had possibly first met in person at the 1919 RAOU congress, held in Brisbane, where Chisholm was then working as a journalist. As a wedding gift, the local branch of the RAOU ordered a complete set of Cayley’s anticipated book The Birds of Australia. The Brisbane Courier reported that, on presentation, with his usual biting wit, Chisholm:

expressed appreciation of the novel but excellent wedding present—novel because it does not yet exist, and excellent because it would be essential, he said, that he should have the works when published.

Then, on New Year’s Eve, Cayley’s sister, Alice, wed the dashing Jack Castle Harris, four years her junior. Both were from artistic families. They had met in Sydney in the early 1920s when Castle Harris was making punched, embossed leather tablecloths in Coogee and Alice was selling her own watercolours of birds. The tall, slender Alice may have lost an earlier beau in 1918 (Herbert Hanson). Castle Harris—also tall—was blonde and blue-eyed, loved the outdoors and had a fine baritone voice, occasionally performing on the radio. He had been discharged from the military after suffering a gunshot wound on the Western Front.

Alice R. Cayley, Scarlet Honeyeater (Myzomela sanguinolenta) 1920s

Cayley senior informally taught his children to paint. Around the 1920s, Cayley’s sister Alice made delicate little paintings of pretty birds. Her birds are similar in attitude to her father’s, but she had her own slightly abstract, oriental approach.

Castle Harris was to go on to take lessons in clay modelling from his cousin Una Deerbon in the 1930s. Alice and her husband visited Una in Melbourne and Castle worked informally with her at the Deerbon School of Pottery while he was employed at Premier Pottery (working on the ‘Remued’ lines). By the late 1930s the couple was back in Sydney, where Castle Harris established his own studio producing distinctive earthenware. Alice is thought to have inspired his use of Australian fauna and flora as motifs. He made gift pieces rather than functional ware: pots and vases entwined with gumnuts, flannel flowers, frill-necked lizards and platypuses. In about 1946 the pair moved the studio to the beautiful town of Wentworth Falls in the Blue Mountains, and then to nearby Lawson. Alice died at Katoomba in 1960, and Castle Harris at Wahroonga in 1967.

Castle Harris’ chunky, vibrant pottery is now collectable, while Alice’s paintings can still be found in collections and art sale houses. Her watercolours are more delicate and decorative versions of her father’s work: kookaburras, finches, wrens and honeyeaters, even a version of Dignity and Impudence. While her father gave some indication of natural habitat in his paintings, Alice’s compositions are somewhat oriental, focused on a loosely painted, centralised background of ornamental branches or grasses. None of her work is dated but, if the few newspaper advertisements for her watercolours are anything to go by, she gave up painting in the late 1920s.

Among those eagerly awaiting Cayley’s big bird book was Donald Macdonald, whose newspaper byline was ‘one of Australia’s greatest nature lovers’. In 1922, Macdonald expected the book would be ‘the last word for many generations ahead’. He praised Angus & Robertson for supporting work by Australian practitioners, when other publishers favoured more established English and European authors. ‘Everybody concerned seems to have caught something of the spirit and purpose which animated Mr. George Robertson in fathering this very fine publication,’ Macdonald wrote in an article for The Argus. The book, he said, would be a credit to Australia.

The enthusiastic Macdonald made the perceptive observation that Cayley ‘has his own impressions and convictions, which while they are not always in harmony with the authorities, he may none the less be able to maintain’. Indeed, dissention among the contributors and Cayley’s intransigence proved to be the project’s undoing.

Discovering that Cayley’s Birds of Australia was even further off than anticipated, and frustrated by the many excuses, the great expense and the ever-increasing complaints from the primary contributors, George Robertson tried to salvage the project. He held meetings with the main players and proposed a way forward. Archibald J. Campbell, a leading Melbourne ornithologist, was now overseeing the science and Barrett the editing. Just before Christmas 1923, Cayley was still hopeful of proceeding as usual, writing to Robertson:

I firmly believe that all (to me imaginary) obstacles can be washed away and we can retreat back to that happy state of affairs which existed between us not so very long ago.

With sufficient material in hand for at least 12 parts, making up three volumes, Cayley assured Robertson that he was confident that ‘we have enough to start publishing right away’. He proposed a plan whereby four volumes a year might be issued, which would complete the project five years from the publication of the first volume, signing off: ‘My name, which is my honour, is in your hands’. A 12-page statement of progress was attached to Cayley’s missive.

It is clear from examining this statement that the undertaking was overly ambitious. Already under way were paintings of the various plumages and habitats of every Australian species, supplementary pen-and-ink sketches, drawings of feather shapes, markings and bills, and a glossary of related terminology. Colour charts, by watercolourist Francesco (Francis) Salvatore Rodriguez, were nearly finished; with the help of Rodriguez, many of the plates of eggs had also been completed. An article by palaeontologist Frederick Chapman on extinct (fossil) birds was ready, although Cayley had yet to do the illustrations. Maps and migratory routes by Tom Iredale were nearly done; the general glossary, Campbell’s key to identification and egg sections were yet to be written; and 2,000 photos had been gathered by appeal to the public. Crayon drawings of genera had been held up by the ‘side-stepping actions of the RAOU Check list committee’. Many sections—Cayley took pains to point out—were novel; he claimed several times that an item was ‘another new idea of mine’. Not least, he was unwilling to drop any of it.

Angus & Robertson Booksellers, Castlereagh Street, Sydney 1920s

The offices and storefront of Angus & Robertson booksellers were in Castlereagh Street, Sydney. The firm, led by George Robertson, promoted Australian authors, including Cayley. Apart from a few years in the mid-1920s, after Cayley had been ejected over differences with Robertson over the ‘Big Bird Book’, their partnership was productive.

Cayley waited anxiously for a reply and when he had not heard back he wrote impatiently on 11 January 1924 asking why, writing pleadingly, ‘I have my family to consider and wish to make arrangements to carry on my profession’. Perhaps to reassure Robertson of his commitment, he added that he had been busy preparing prompt cards for promotional talks suitable for journalists, lawyers, doctors, pastoralists, schools of art, and so forth.

On 14 January Robertson, just returned from a summer break, responded firmly: ‘I have no intention of discussing the matter, even briefly. There has been far too much of that already’.

Robertson advised Cayley to let Campbell and Barrett carry on until the end of the year, while he, Cayley, got on with his drawing. He hoped that by then ‘the situation will have cleared, and we will be in a position to start printing and publishing without fear of being hung up’. Robertson knew Cayley well, ending the brief letter with some sage advice:

Now don’t argue. Do your work, and let Campbell and Barrett do theirs, and I have no doubt that by the end of the year our path will be clear of the impediments which at present beset it.

On 18 January 1924 Cayley wrote to Robertson that he was pleased that the project was proceeding and thanked him, ‘the more so since my native buoyancy has suffered of late’. Still, he ventured, he would like to ‘submit one or two points’. Ignoring Robertson’s advice, his argumentative ‘points’ stretched the letter to three pages and included a request for an increase in annual salary to 500 pounds.

Cayley’s impertinence, his ‘native buoyancy’, was the last straw for Robertson, who, a few days later, sent a terse letter of reply. It stated firmly that he was already paying Cayley 97 pounds 10 shillings a year and regarded his claim as ungrateful. Hence, wrote Robertson: ‘I have decided to abandon the project … our business relations now come to an end’.

In little over a month, four years of intense and costly work had unravelled. Still, Cayley could not believe it. He seemed surprised, describing it as ‘a knock out’ blow, but thanking Robertson for his kindness and generosity. Again, he argued. Robertson’s curt reply chided, ‘why write long letters dragging in extraneous matter, and hinting at ulterior motives’. His decision, Robertson explained, was based on ‘the unsettled state of the ornithological world’. At some stage in the unfolding of these events, Cayley was famously ordered off the publisher’s premises.

The end was announced to the public in the April 1924 issue of Emu, with a discreet notice stating that ‘we sincerely regret that, owing to unforeseen circumstances, we have been compelled to abandon the publication of Cayley’s Birds of Australia’. There were a few complaints and wide disappointment, for the work had been eagerly anticipated and most amateur and professional ornithologists had contributed in some way to the project.

Apart from Cayley’s overblown enthusiasm, the RAOU checklist had been at the heart of the strife—the ‘unsettled state’ and ‘side-stepping actions’ of the ornithological community that Robertson and Cayley had referred to in correspondence. The compilation of a checklist was guaranteed to be controversial given the range of views on bird species and their names. Aside from the scientific considerations, many common names had long been in use. Different names were also used in different parts of the country, which raised the sticky problem of which name was to take precedence. Wars were waged over such issues as whether the common name of the Black Duck, with its grey-brown plumage, should be changed instead to ‘Grey Duck’. Should the much-loved names Jacky Winter and Willy Wagtail make way for the more informative Brown Flycatcher and Black and White Fantail? Individuals defended their views on the identification, naming and ordering of species and subspecies with great ferocity. The result, as far as the bird book was concerned, was an ever-changing list of birds with which to grapple.

There had also been clashes between Cayley and some of the main players, certainly the checklist-championing Campbell and the taciturn Barrett. Cayley’s sense of ownership was understandable after so many years of involvement with, and input into, the publication, not to mention the fact that his name had been so prominently attached to the project. However, the book had been Robertson’s idea and, according to Cayley’s friend Alec Chisholm, Cayley could get people offside with his strident opinions. Campbell, an elder in the Presbyterian church, called for concerned ornithologists to pray for ‘divine intervention’ to change Robertson’s mind. But none was forthcoming and Robertson, who had been supportive for far longer than he could afford, had had enough.

Robertson, however, had apparently decided to salvage what he could. He took the opportunity to announce in a letter to the editor of Emu that Angus & Robertson intended to publish Australian Bird Biographies. Beginning early in 1925, it would be issued in parts and would contain illustrations of eggs of nearly every species and engravings from photographs. Robertson was prepared to take risks to promote Australian work and was generally repaid, though not in this case: Australian Bird Biographies, using the material in hand from the abandoned bird book, never eventuated.

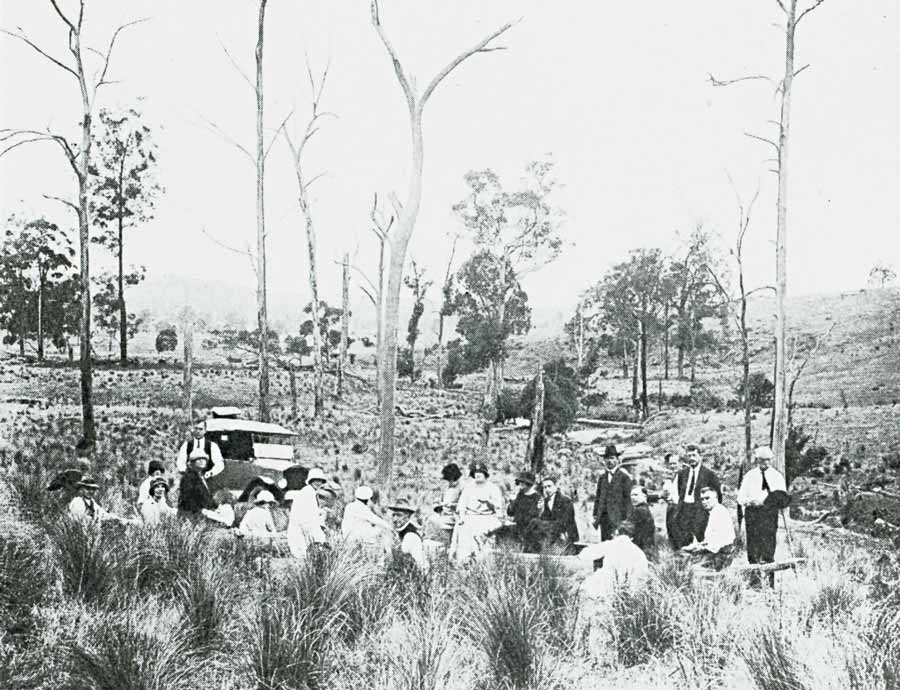

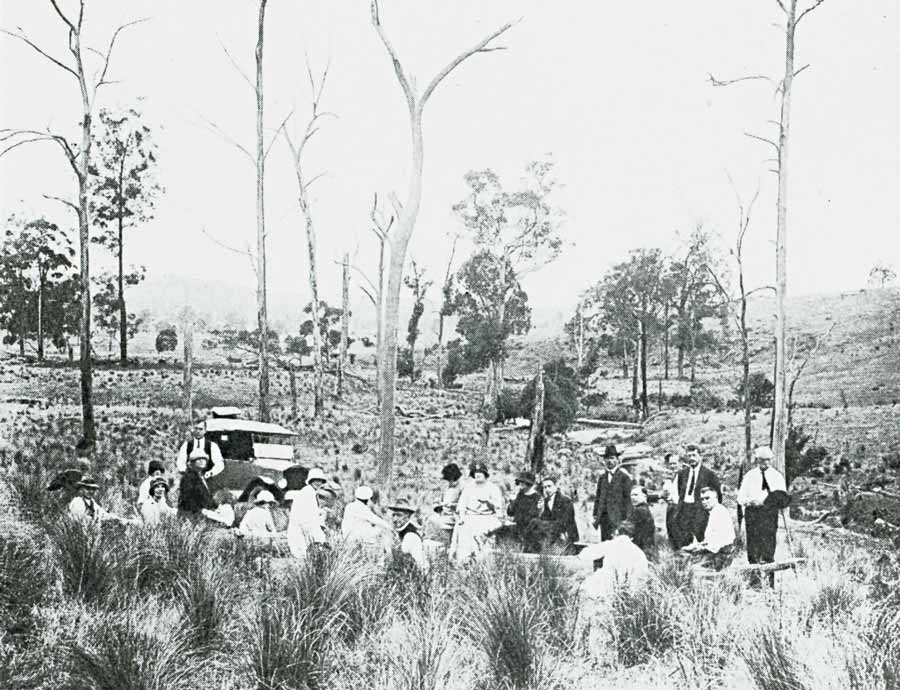

Anthony Musgrave, ‘Bird Picnic’ Groups, Wallarobba 1926

In 1925 members of the New South Wales branch of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union were invited to a bird picnic to celebrate the declaration of Wallarobba Sanctuary, near Barrington Tops. The branch had been instrumental in securing the area as a sanctuary for birds and other wildlife. Cayley and five other members made the trip and in subsequent years Cayley returned to the district to sketch birds.

Despite the altercations and financial loss, Robertson did not hold a grudge. He was fond of Cayley and his wife Beatrice. When Beatrice died suddenly in 1927, Robertson generously organised for some money to be forwarded to Cayley. The humbled Cayley sent ‘heartfelt thanks’ and admitted that he was lonely and dreaded ‘the long nights’.

Tragically, Cayley’s beloved Beatrice, who Chisholm described as ‘a good and gallant woman’, had delivered a stillborn daughter in January and had died soon after, aged just 38. When Beatrice died, Neville Clive was six and a second son, Glenn Digby, born in 1924, was two. It must have been hard for Cayley to keep up his ornithological travels and work. His mother Lois moved into his Rose Bay house to help, and remained there until about 1938. When the boys were old enough, they were sent to boarding school and never really got to know their father well.

Cayley had been a core member of the RAOU from the time he began his association with the group. In 1922, he was secretary of the newly formed New South Wales branch (which was also the ornithological section of the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales). At the Adelaide Congress that year, he represented New South Wales and was praised for not only presenting the sole report for any state, but for ‘a magnificent piece of work’ when he reported that the group had successfully stopped timber felling in the beautiful, eucalypt-covered and rainforested National Park in Sydney (now Royal National Park). Cayley described to the meeting how it had been discovered that the Trustees for the park had signed a contract with a coal company for the felling of the park’s timber on a large scale. He stated that the destruction would be:

disastrous, not only to the value of the reserve, as an example of virgin forest, but to the existence of the birds and animals for which it was supposed to be a sanctuary.

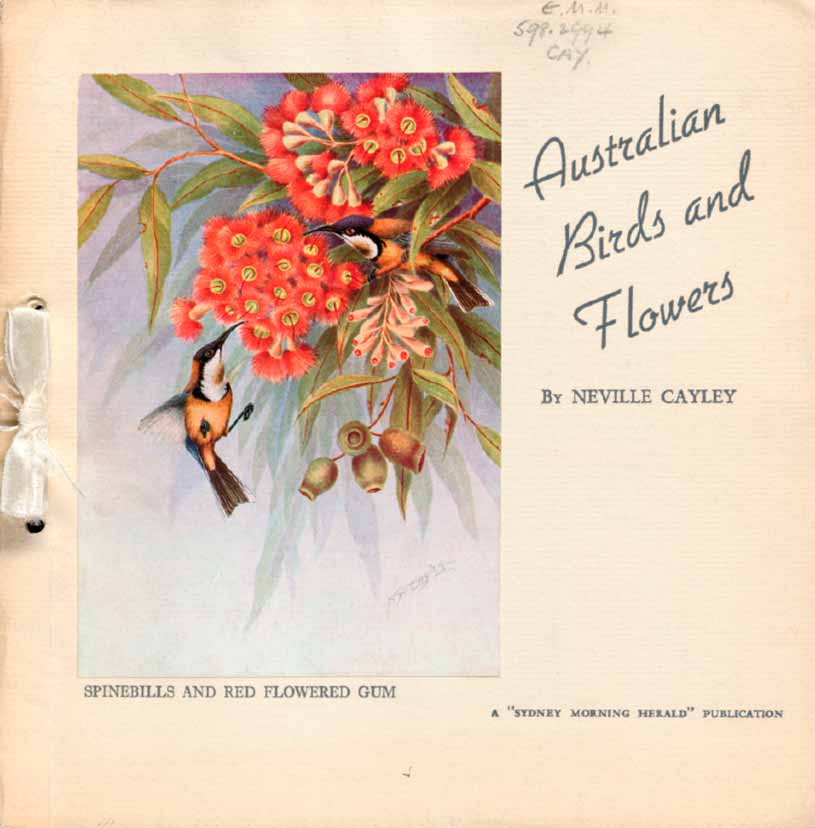

Title page of Feathered Minstrels of Australia (1926) by A.H. Chisholm and N.W. Cayley

Cover of Australian Birds and Flowers (1938) by Neville Cayley

From the late 1920s, and throughout the 1930s, Cayley’s most productive years, he published widely, both as an author and illustrator. His works include several booklets aimed at reaching an ever-broader audience in order to educate them about birds.

The branch had raised a deputation of likeminded societies that had been successful in stopping the logging and in having the Board of Trustees restructured. Cayley, an effective advocate for surf lifesaving, was becoming a voice for the birds.

Early in 1925, the New South Wales branch of the RAOU received another cry for help, this time from Mrs J.J. de Warren of Dungog. She and a few neighbours wanted to have their properties declared a sanctuary, but their application to the Chief Secretary had been refused. The RAOU rallied and presented the Minister with ample evidence of the area’s significance for bird life, including its proximity to Barrington Tops. The decision was reversed. To celebrate the declaration of Wallarobba Sanctuary, Cayley and others were invited to a bird picnic. In October, a party of six Sydney members took the train to Dungog, arriving at midnight. They were met by their hosts and ferried to various homesteads. The properties may not have been quite as hoped—they had mostly been cleared for grazing and dairy farming. This is evident in a photograph of the happy gathering taken by Cayley’s friend Anthony Musgrave, an entomologist at the Australian Museum who had studied art under Julian Ashton. However, in the more wooded areas birds were plentiful and some of the locals suggested that rarities, such as the Turquoise Parrot and Plains-wanderer, occurred in the area occasionally, though they were not in evidence on the day. Cayley befriended the locals and returned several times, possibly to the de Warrens’ property, to paint.

But advocacy did not pay the bills. In 1925 Cayley began to write a weekly article for The Sydney Mail. It brought him a small but regular income. The Our Birds series, illustrated with pen-and-ink sketches, aimed to cover the habits of popular birds and rarities. Cayley was billed as ‘a member of the British and Australian Ornithologists’ Union’. The series started in the second week of January 1925 with flightless birds—the Emu, the Cassowary and penguins. Rarities included the Scarlet-chested Parrot, Turquoise Parrot and Bourke’s Parrots, all of which appeared in the second-last article in the series.

A new series began immediately, in May 1926. Like its predecessor, Feathered Minstrels of the Bush also started with an odd combination: it featured the Masked Gannet (not much of a songster!) and the more melodic Grey Shrike-thrush. Someone, perhaps Cayley himself, had taken photos of the gannet, which accompanied the article. The shrike-thrush was illustrated, as was to be usual, in grey tones, which reproduced more attractively than the spare sketches in Cayley’s previous series. The final minstrels were the honeyeaters, appearing at the end of March 1928.

At the same time that Cayley was writing his regular column, he was working on a similarly themed booklet with text by his friend Alec Chisholm: Feathered Minstrels of Australia. Its purpose, Chisholm wrote, was to ‘render some justice to the vocal abilities of certain birds of Australia’, which tended to be eclipsed in the minds of many Australians by the birds of ‘home’—that is, England. The intention was to publish a series of four booklets, but only the first, its release timed for Christmas 1926, saw the light of day. The articles covered six songsters: ‘Lyre-tail: a Master Mocker’, ‘The Flashing Magpie’, ‘The Grey Thrush: The Woman’s Bird’, ‘The Australian Skylark’ (Horsfield’s Bushlark), the White-throated Gerygone and the Silvereye. With a bit of artistic licence, Cayley drew the birds singing their hearts out with beaks wide open.

In 1926, Cayley’s charming children’s book The Tale of ‘Bluey’ Wren came out. Published by Lonsdale and Bartholomew, the book was written and illustrated by Cayley. His oldest son Neville Clive was then four, so Cayley may have tried out the story on him, but it was aimed at an older age group. The text was both appealing and educational:

The eggs of Blue Wrens, and all other kinds of Wrens, take about fourteen days to hatch. So Bluey was kept on alert for two weeks. Then the shells broke and the babes appeared. What naked, ugly mites they were, with mouths as big as their fat little bodies! But in a very short time feathers began to show, and at three weeks old they were as fluffy as powder puffs. Then they were ready to leave the nest.

Neville William Cayley, The Tale of ‘Bluey’ Wren c. 1926

Aimed at educating children about birds, The Tale of ‘Bluey’ Wren came out in 1926.

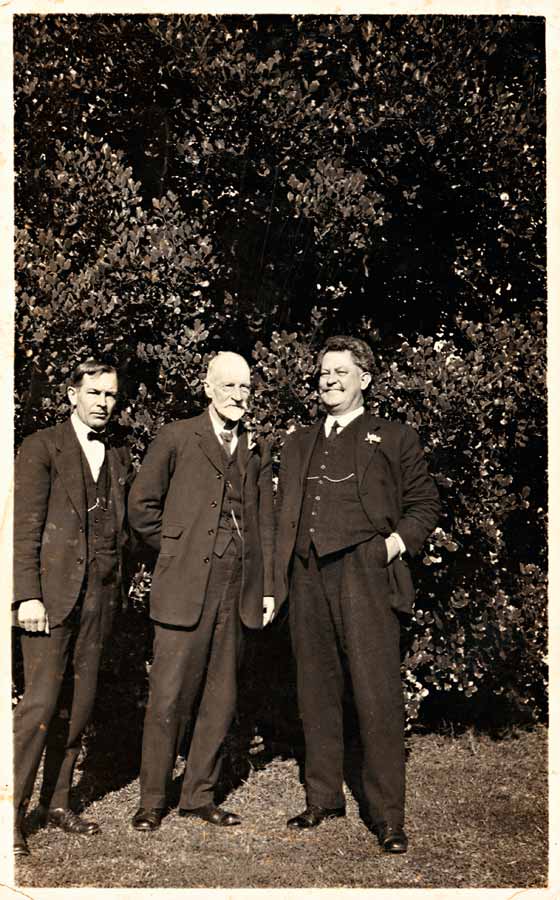

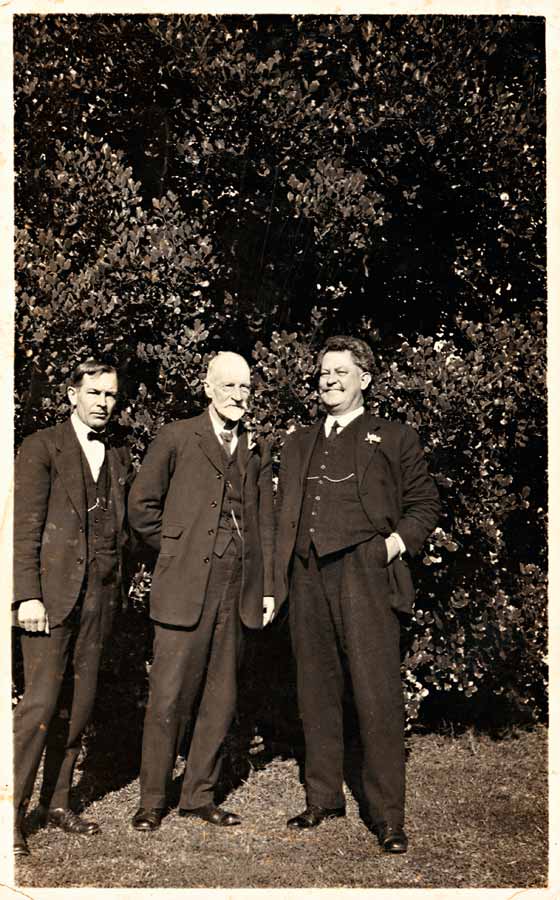

Henry Luke White, Photograph of Neville Cayley, Archibald Campbell and Sidney Jackson, 22 May, 1921

In preparation for Angus & Robertson’s ‘Big Bird Book’, Cayley (at left) worked with Archibald J. Campbell (centre), who oversaw the science, and Sidney Jackson (at right), curator of the H.L. White Collection, who supplied him with eggs to illustrate. This photograph was taken by White in the garden of his property, Belltrees, at Scone, in 1921.

Cayley charted Bluey’s adventures as he courted Jenny Wren, chose a site and built a nest, did his share of incubation, bathed and preened, fended off rivals and would-be predators, fed the demanding chicks and generally made himself ‘useful’ by eating insects and gracing gardens.

Some of the illustrations of birds and eggs (see portfolio section) that Cayley had painted for his much-touted but abandoned bird book, teamed with many black-and-white sketches by his late father (by permission of the Trustees of the Australian Museum), were at last published in Angus & Robertson’s two volume work The Illustrated Australian Encyclopaedia (1925–1926). Gregory Mathews’ taxonomy was applied, which gave Cayley more species to worry about than was necessary. For example, in the plate featuring the eggs of thornbills there are 18 species, only 11 of which are currently recognised. It was typical of Mathews to split species into two on the slimmest suggestion of any variation.

Cayley and Rodriguez developed a method for producing very lifelike illustrations of eggs. The eggs were first photographed and their exact shapes transferred to the sheet; they were then handcoloured to match the specimens and the appropriate shadows were spray-painted on. Cayley travelled to the home of the great collector Henry Luke White, who had some 4,200 clutches of Australian bird eggs. At Belltrees, Scone, White’s somewhat eccentric but talented curator and field collector, Sidney Jackson, looked after Cayley. The two thoroughly enjoyed themselves, baiting each other like schoolboys. Cayley would apologise to Jackson for accidently smashing some unique set of eggs, presenting him with a crumbling clutch of worthless shells in support of his subterfuge. In return, Jackson would place a large artificial spill of ink or a glowing imitation cigar on one of Cayley’s finished paintings.

In the late 1920s, after receiving the note from George Robertson following Beatrice’s death, Cayley felt that he could once again enter the offices of Angus & Robertson. He sought out Robertson and tearily thanked him. Robertson may have been expecting him, because he immediately told the startled Cayley that he could start again, adding half-jocularly that ‘I shall be glad, Cayley, if you do not get in my way any more than you can possibly help’.

Robertson, well aware that an Australian bird book was long overdue, had given Cayley another chance. This time the initial outlay was not a problem: the New South Wales branch of the influential Gould League of Bird Lovers had agreed to sponsor a field guide to birds, and Cayley was the best man for the job.

The Gould League of Bird Lovers had been established in 1909 in Victoria, to promote the protection of birds and to discourage egg theft, a reaction to the popularity of egg collecting and pea-guns among boys. Named for the ‘father of Australian ornithology’, John Gould, the League promoted appreciation and understanding of birds. It actively countered the culture of killing birds for sport and campaigned for the establishment of nature reserves. Its President was the Prime Minister, the Hon. Alfred Deakin, and one of the main sponsors was the Australasian Ornithologists Union (later Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union), also formed in Victoria the same year.

The League declared an annual Bird Day, similar to the already-established Arbor Day. The first Bird Day was held on 29 October 1909, during which schools throughout Victoria celebrated birds through various events and contests, including essay and sketching competitions. There were even prizes for the first boy or girl to induce a wild bird to land on them.

A great many children paid the membership fee of a penny, taking the pledge to protect native birds and to not take their eggs. The League was soon producing educational material and also ran field days for the public. By the second Bird Day membership was approaching 30,000 and in 1911 it was almost 50,000. The idea took off next in Tasmania and Queensland and multiple branches sprang up across those states. New South Wales held its inaugural Bird Day in October 1911; two years later its membership topped 25,000. The League was a hugely successful concept that soon garnered patronage in high places, from governors, premiers and ministers. In 1938, the centenary of John Gould’s arrival in Australia, current membership across the four states was estimated to be three-quarters of a million.

In New South Wales, the Department of Education embraced the idea and teachers were encouraged to involve their pupils. The head of that department was almost always the President of the League. From the 1930s the movement was regularly assisted by Cayley’s involvement— in particular by his contribution of artwork, which appeared on membership certificates and in the magazines and educational sheets that went out to members and schools. However, their earliest collaboration may have been in 1920 when the League published a description and illustration of the Malleefowl by Cayley in its Supplement to the Education Gazette.

Thanks to the League, in the late 1920s Cayley was busy writing and illustrating what was to become his magnum opus: What Bird Is That? A Guide to the Birds of Australia. This time, there was much less fanfare about its preparation, and it was by Cayley alone, although he received considerable help from his colleague, the respected amateur ornithologist Keith Hindwood. In order to avoid the fate of its predecessor, What Bird Is That? was limited in scope—that is, manageable in terms of its completion. It was to be a field guide, with every species illustrated, the meaning of each species’ scientific name explained, and brief descriptive text on the bird’s ‘distribution’, ‘nest’ and ‘eggs’, with ‘notes’ setting out other names, characteristic behaviours and diet. The guide was laid out in such a way that, it was hoped, it would be easy for anyone to identify the birds they saw. The precursor can be seen in Cayley’s series for The Sydney Mail. He presented the birds largely categorised according to their main habitat: birds of lakes, streams and swamps; of ocean and seashore; of heath and undergrowth; of shores and river margins; of blossoms and outer foliage; of mangroves; of open forest; of brushes and big scrubs, and so on.

The book was warmly welcomed, although there were initial doubts about its worth and saleability. It was not Cayley’s finest work illustratively: the images of birds were tiny, a dozen or more to a page, and the layout was quirky: rather than grouping birds together in Families, for instance, they were organised according to habitat. As expected, disagreement over bird names continued. Cayley, for example, chose the clumsy ‘Lyrebird Menura’ over ‘Superb Lyrebird’, and used the name ‘Albert Menura’ in preference to ‘Albert’s Lyrebird’. However, at least some reviewers considered that despite Cayley’s overuse of the hyphen, his ‘Dollar-bird’, ‘Heathwren’, and ‘Log-runner’ were an improvement on the checklist’s ‘Eastern Broad Billed Roller’, ‘Chestnut-tailed Ground Wren’ and ‘Southern Chowchilla’, respectively.

Neville William Cayley, Some Birds of the Heath and Undergrowth 1931

A typical plate from Cayley’s What Bird Is That? (1931), which was the first field guide to the nation’s birds and had no competitors for three decades. The book was revolutionary: it was affordable and it allowed anyone to identify the birds they saw—the first publication to do so. It has been revised, reformatted and republished many times since.

Despite its faults, the guide eventually took off to become the most popular and persistent bird book ever likely to be produced in Australia, if not the world. At last Australians had a reasonably priced book that would allow them to identify the birds that they encountered. The Gould League of Bird Lovers, an organisation concerned with birdwatching and education, had accomplished what the RAOU, with its concern for scientific rigour, could not.

The title was ingenious—the memorable What Bird Is That?. The phrase was often used in a popular dinner table game in the 1860s and 1870s that was based on paragrams (verbal puns). A question would be asked to which the other players had to try to come up with an answer—for example, what bird is that which it is absolutely necessary we should have at our dinner, and yet need neither be cooked nor served up? A swallow. What bird is that whose number, singular or plural, is difficult to determine? The cock-a-too—that is, the cock or two. But, of course, ‘No question is more frequently on the lips of bushlovers’, as G. Ross Thomas, head of the Department of Education, stated in the foreword to Cayley’s book, ‘occasioned by the bird on the wing, or on the tree in quiet contemplation, or by the lilt of a song. No question could be more spontaneous’.

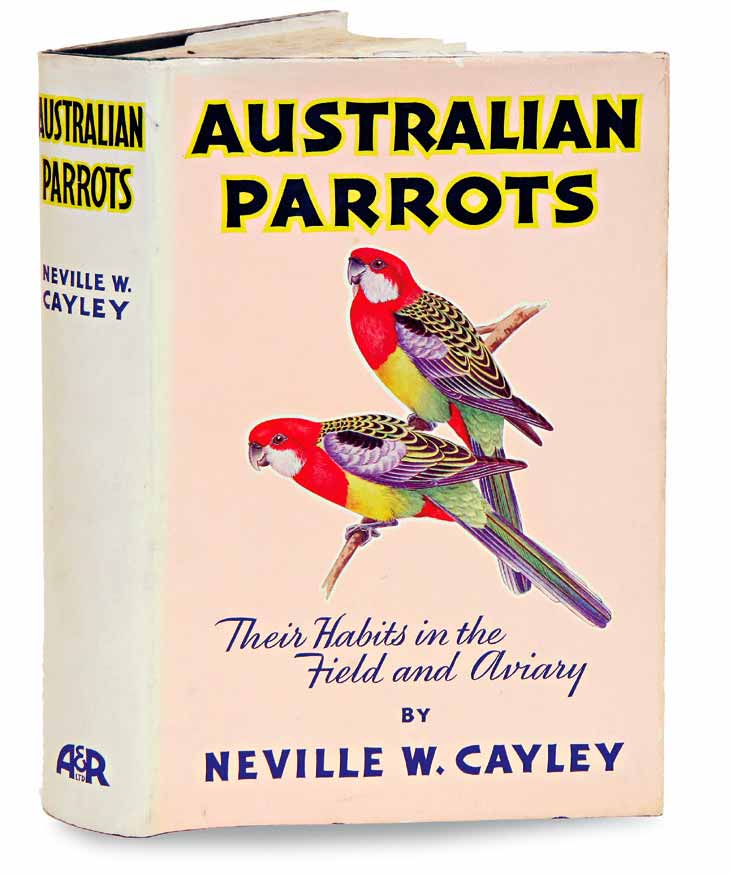

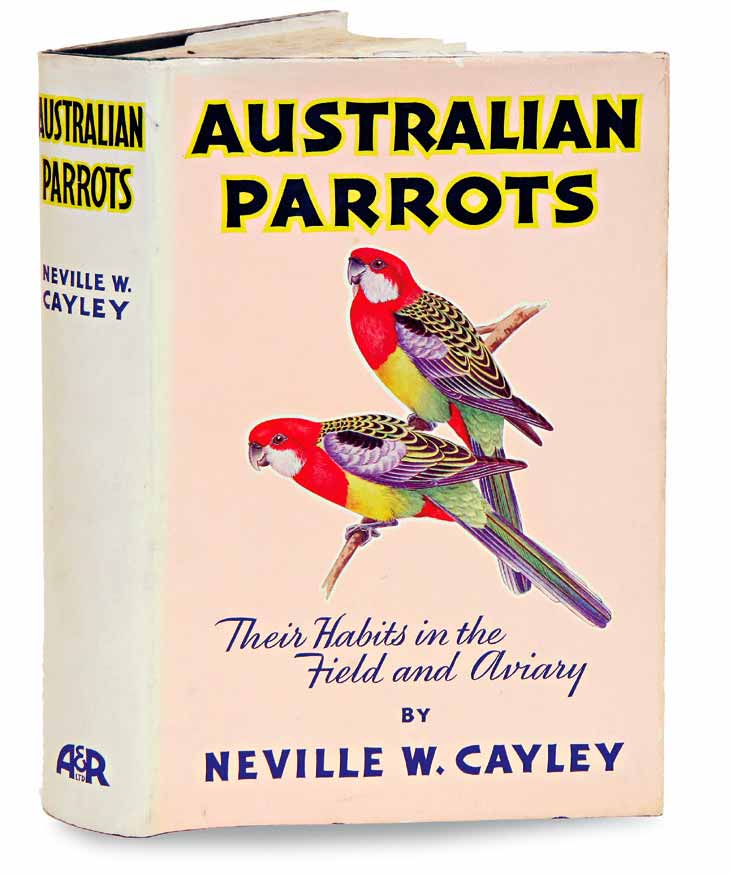

Dust jacket of Australian Parrots: Their Habits in the Field and Aviary (1938) by Neville W. Cayley

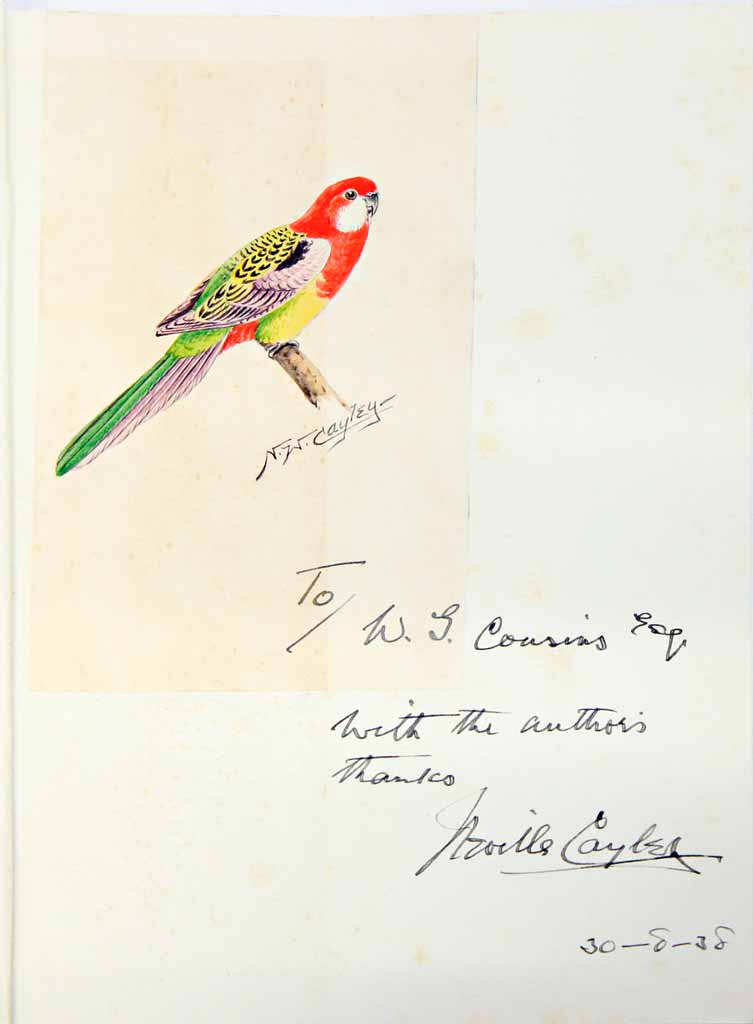

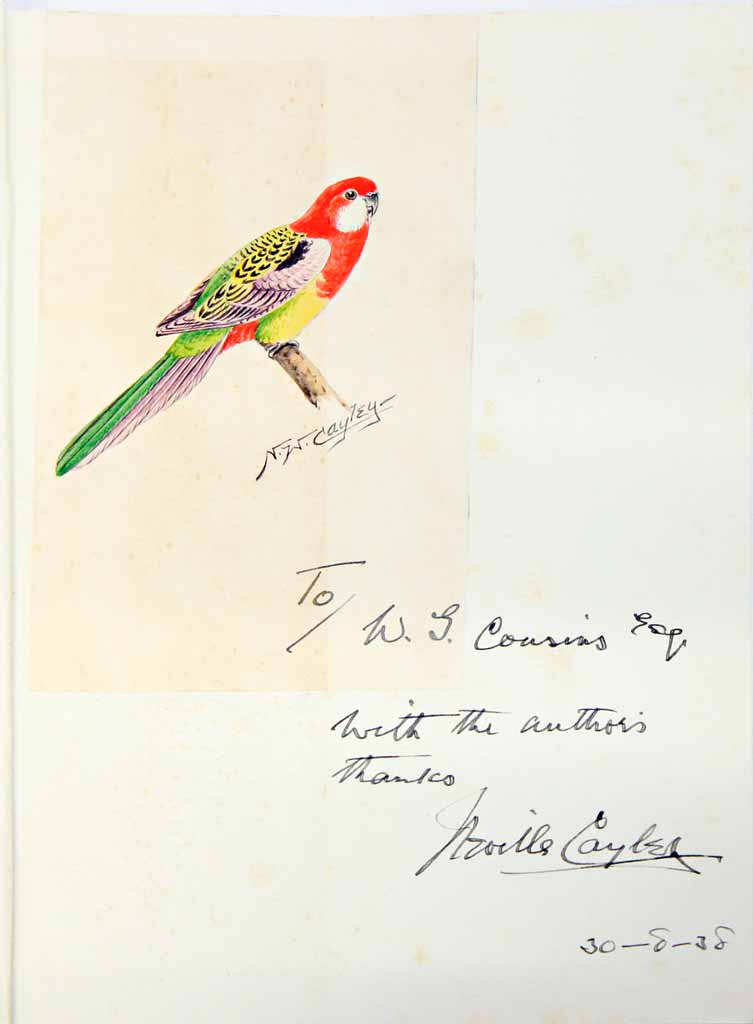

Neville William Cayley, a sketch of an Eastern Rosella and an inscription to W.G. Cousins, 30 August 1938, in a copy of Australian Parrots: Their Habits in the Field and Aviary

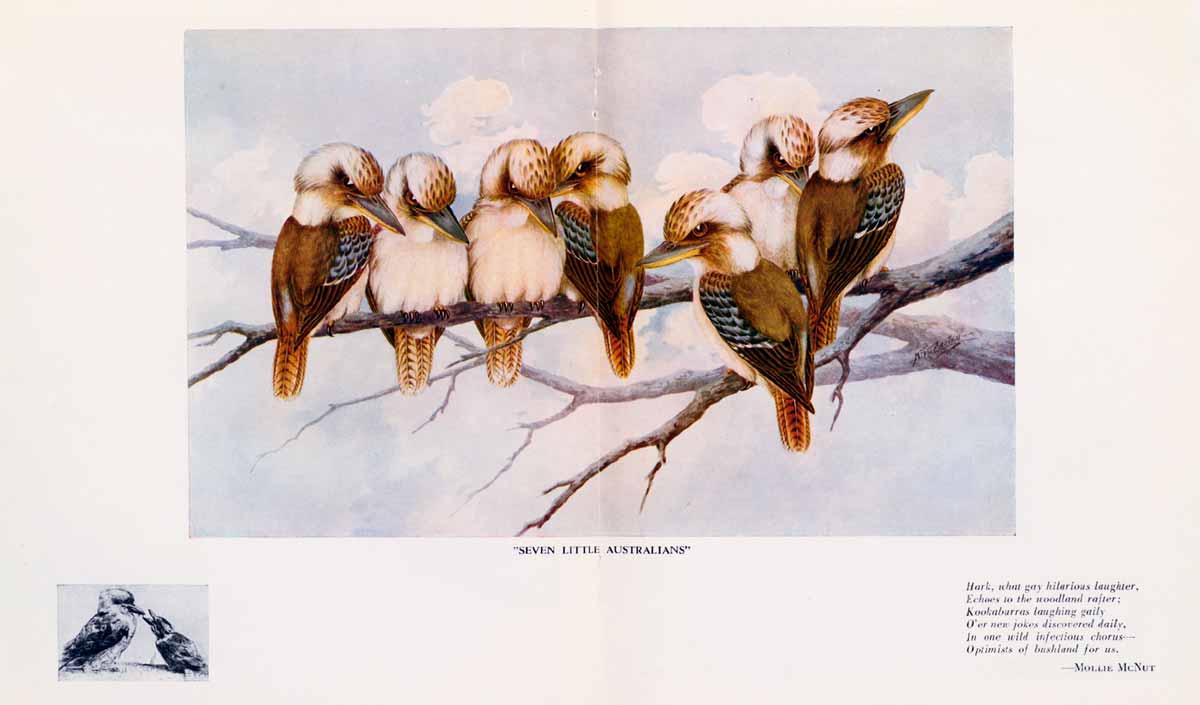

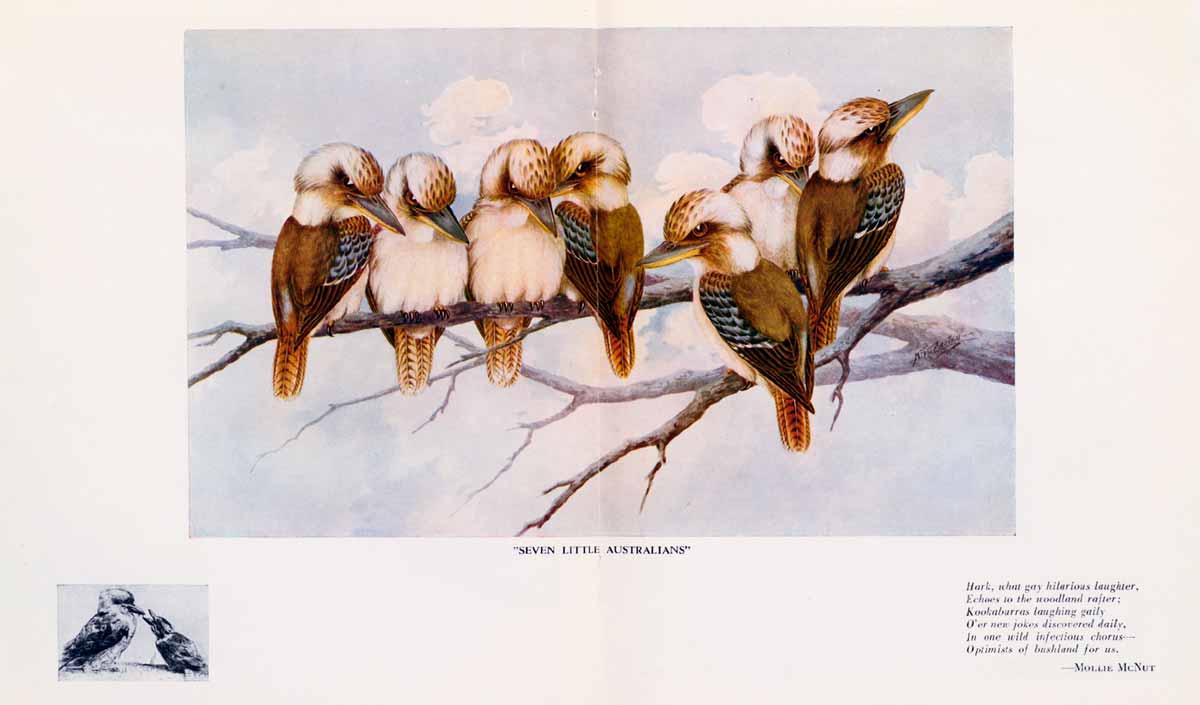

Neville William Cayley, Seven Little Australians 1931

The title Seven Little Australians and the attitudes of Cayley’s kookaburra group were reminiscent of his father’s wry approach to the subject. The picture was one of several illustrations produced for Dorothy Drewett’s book Laughing Jack, The Kookaburra, for young readers. Both Cayley and Drewett were members of the Fellowship of Australian Writers.

Neville William Cayley, The Birds Take Flight 1934

The Sydney Mail of 14 February 1934 published an article about the opening of the duck-shooting season and asked Cayley to provide an illustration, just as his father had been asked to illustrate its ending in 1889 (see image).

Nevertheless, the inspiration for the catchy title was probably the now forgotten American publication What Bird Is That?, subtitled A Pocket Museum of the Land Birds of the Eastern United States Arranged According to Season. The contents of that book too were clearly influential. It had, for example, a ‘map’ of the parts of a bird and attractive little illustrations of 301 birds by Edmund J. Sawyer, arranged many to a page in ‘cabinets’ according to season and migratory status, such as the ‘Winter Land Birds of the Southern United States’.

The all-Australian What Bird Is That? was launched on the Gould League’s Bird Day celebration for 1931. In return for sponsorship Cayley assigned four-tenths of his 10 per cent royalty to the League. With the initially slow sales, royalties were meagre and in 1935 the cash-strapped Cayley offered to sell his share of the royalty to the League for 300 pounds. Reluctantly, the League’s Council agreed. In time it proved a bad decision on Cayley’s part. Sales were poor at first but, thanks to United States servicemen who were on R and R in Australia during the Second World War, books flew out the door as souvenirs, and royalties came rolling in to the League. Perhaps, too, the increase in sales was evidence of the success of the League in educating children to appreciate birds, as those children grew into adults and joined the book-buying market.

The League made good use of the funds for its conservation and educational activities and on Bird Day 1935 announced an annual scholarship in memory of Cayley’s father, to be established with the royalties that Cayley had handed over to the League. The Cayley Memorial Scholarship, initially valued at 50 pounds, was tenable for two years. It aimed to facilitate research into ornithological issues and, for the next 75 years, assisted many students.

Cayley was involved in another book for the Gould League’s Bird Day of 1935, which was distributed to every public school in New South Wales. Published by Angus & Robertson, Feathered Friends again had a foreword by Thomas. A general introduction to Australian birds by Chisholm was followed by six articles by well-known ornithologists and naturalists. Cayley edited the publication, contributed an engaging article on the Blue Wren (now the Superb Fairy-wren) and provided several coloured illustrations.

That year the League also introduced the annual Gould League Notes, a magazine that was also distributed to every public school in the state, and to private schools with membership, until 1967. Well into the 1940s Cayley provided gratuitously the descriptive notes and the illustration of a featured bird for the coloured plate that brightened each issue.

Neville William Cayley, Wedge-tailed Eagle 1934

The build-up to the abandoned bird book had brought Cayley some extra renown but, once freed from the burdensome task, he soared away. The late 1920s and the 1930s were exceptionally busy and productive times. He began work on a series of new books, painting and writing at such a pace that a new Cayley publication came out almost every year during the 1930s. Beginning with What Bird Is That? (1931), over this period he researched, wrote and illustrated three further substantial works: Australian Finches in Bush and Aviary (1932), Budgerigars in Bush and Aviary (1933) and Australian Parrots: Their Habits in the Field and Aviary (1938), all published by Angus & Robertson.

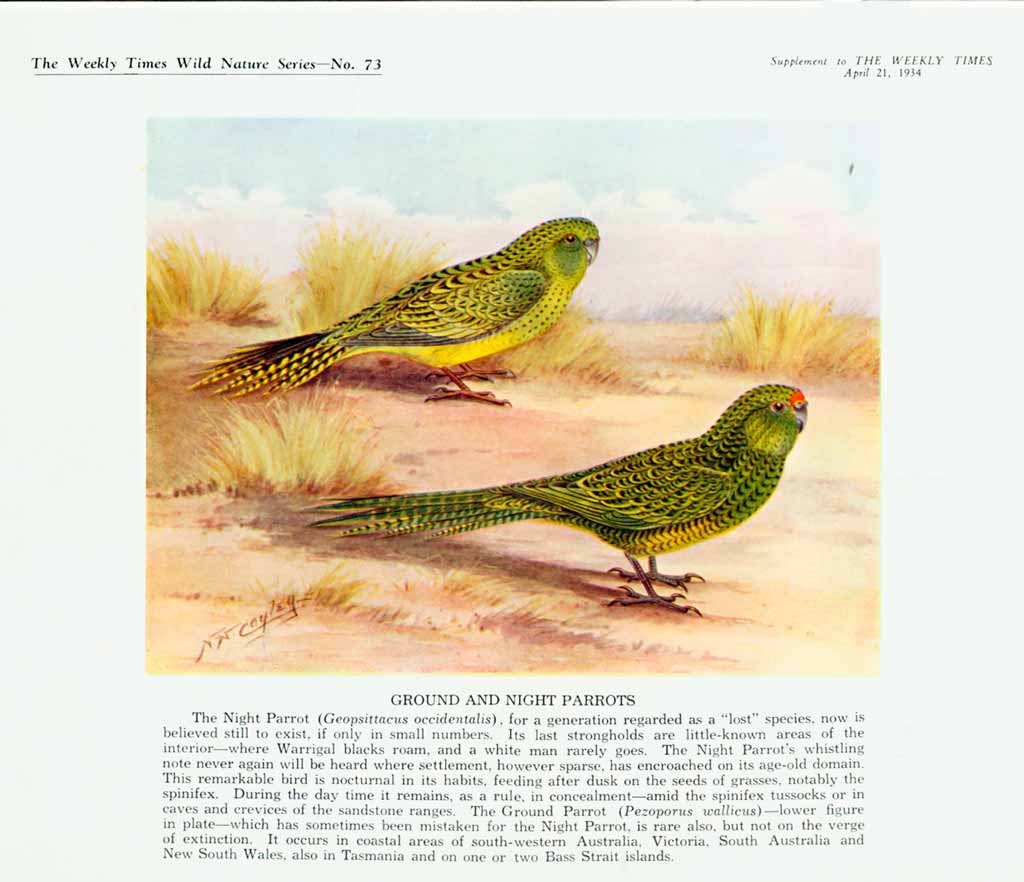

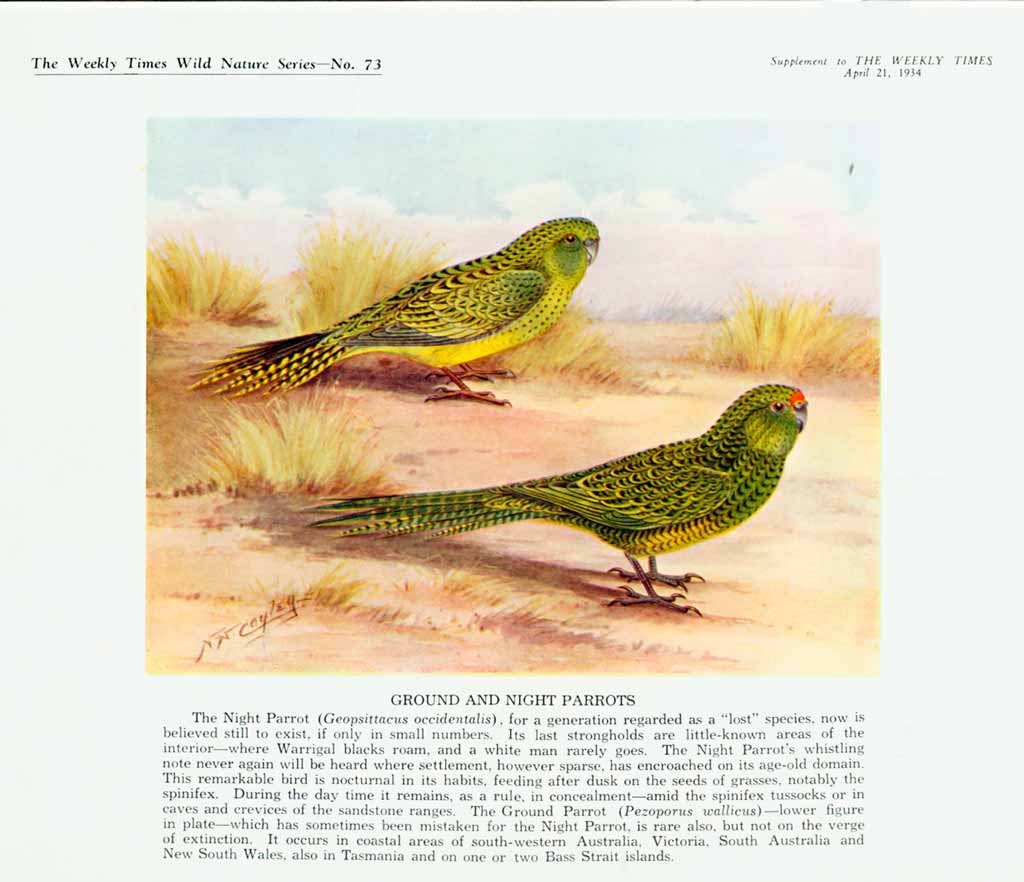

Neville William Cayley, Ground and Night Parrots 1934

Cayley’s illustrations were used and reused to illustrate many articles on nature, a popular subject at the time. He provided a picture of a Wedge-tailed Eagle to illustrate an article by Charles Barrett for a Weekly Times Wild Nature Series, published on 14 July 1934 as a supplement to The Weekly Times of Melbourne. The illustration was republished, along with several others from the series, in The Weekly Times Wild Nature Book (1934), which had articles on a mixture of Australian and international animals.

Similarly, Cayley painted the rare and elusive Night Parrot behind a Ground Parrot to illustrate the differences between the two birds. The illustration was used several times, including by Cayley’s colleague Charles Barrett, who reproduced it to illustrate his Weekly Times publications (1931–1934) and again in his 1949 book Parrots of Australia.

Cayley also completed another large illustrative project, What Butterfly Is That? (1932) by Gustavus Athol Waterhouse, a prominent entomologist based at the Australian Museum. The 34 plates depicted some 339 species of butterfly in colour. It showed their upper and lower wings and depicted the two sexes where they differed. It also included black-and-white illustrations of larvae. Cayley’s father had also painted butterflies and moths.

Both Cayley and his father also produced illustrations for newspapers. Cayley junior completed several such pictures in the 1930s. His finches graced The Sydney Mail calendar for 1932. In 1934 he provided a black-and-white drawing for The Sydney Mail to illustrate an article on the opening of the duck-shooting season, just as his father had done to indicate the end of the season 45 years before (see image 1 image 2 and image 3). Cayley junior’s sketch, entitled The Birds Take Flight, showed the ducks fleeing, whereas his father’s was more graphic. The difference demonstrates the shift in public attitudes that the Cayleys themselves had helped bring about. As the President of the Gould League pointed out in 1936:

Although some of the paintings of the late Neville Cayley, depicting dead birds, would possibly arouse adverse criticism to-day, it must be remembered that his last work was done 15 years before the introduction of the Bird Protection Act.

When, in 1931, Alec Chisholm and Dorothy Drewett jointly published a children’s volume that combined Chisolm’s Hail, the Kookaburra, on the bird’s biology, with Drewett’s Laughing Jack, the Kookaburra, a biologically accurate narrative about the merry, murderous habits of a party of kookaburras, Cayley provided some of the illustrations. He displayed a touch of his father’s propensity to coin sentimental titles: a pair of kookaburras is captioned Love’s Old Sweet Song, while a group gathered along a branch is Seven Little Australians (see image).

During the 1930s Cayley also provided illustrations for publications that included: Youth Annual (1930), a collection of verse and stories by notable Australian writers; Australian Birds and Blossoms (1931) and several other Sun Nature Books by Charles Barrett, published between 1931 and 1936; Water Life (1934), a 43-page Sun Nature Book by Charles Barrett, Gilbert Whitley and Tom Iredale; Australian Birds and Flowers (1938), a 28-page supplement to The Sydney Morning Herald; and Some Australian Birds (1934), a small book of poems by W.H. Honey. He wrote and illustrated an article on parrots for the 1937 Australia To-day, an annual publication by the United Commercial Travellers Association of Australia. The publication, and Cayley’s article, aimed to promote Australia, and Cayley’s contribution appeared together with pieces on Australian development by the Prime Minister, Joe Lyons, and on civil aviation by the Controller-General of Civil Aviation, again illustrating how successfully birds had been placed on the national agenda.

In 1938 Cayley also found time to illustrate menus for the Orient Liner SS Orana . The various birds were captioned ‘the Australian scarlet-breasted robin’, ‘long-tailed grass finches’, ‘Gouldian painted grass finches’, ‘rosella parrakeets’, ‘cockatiels’ and ‘rufous-fronted fantails’. Among various other painting and publishing projects, Cayley also continued his regular illustrations and descriptive notes for the Gould League and illustrations for Emu . As an expert on, and advocate for, nature, he sent letters to the editor of various newspapers drawing attention to items of interest such as the mass bird deaths in a 1932 heatwave in Queensland and, also in Queensland, the slaughter of koalas and possums for their fur.

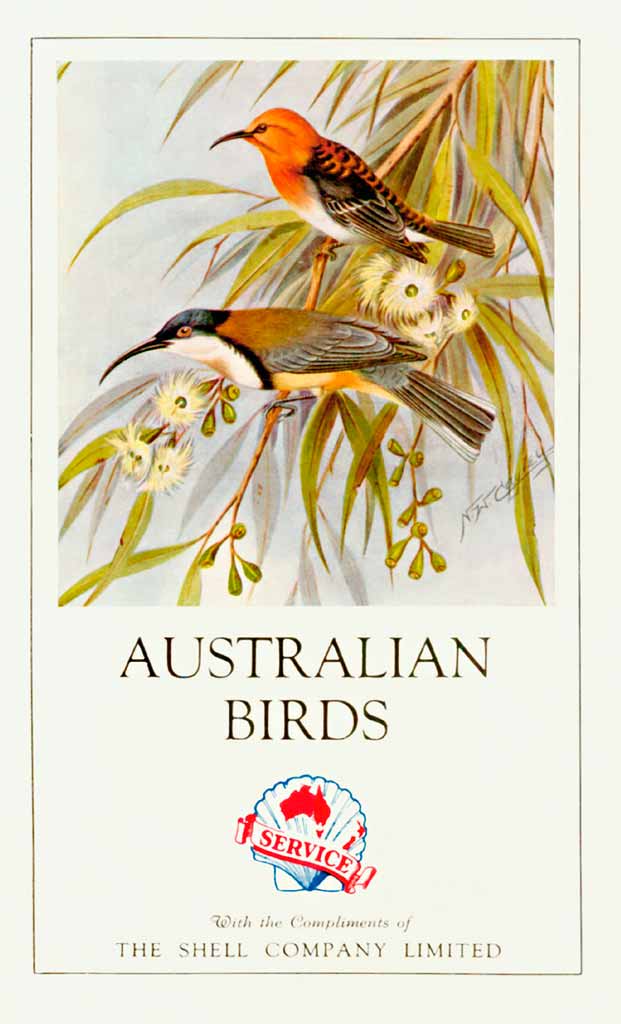

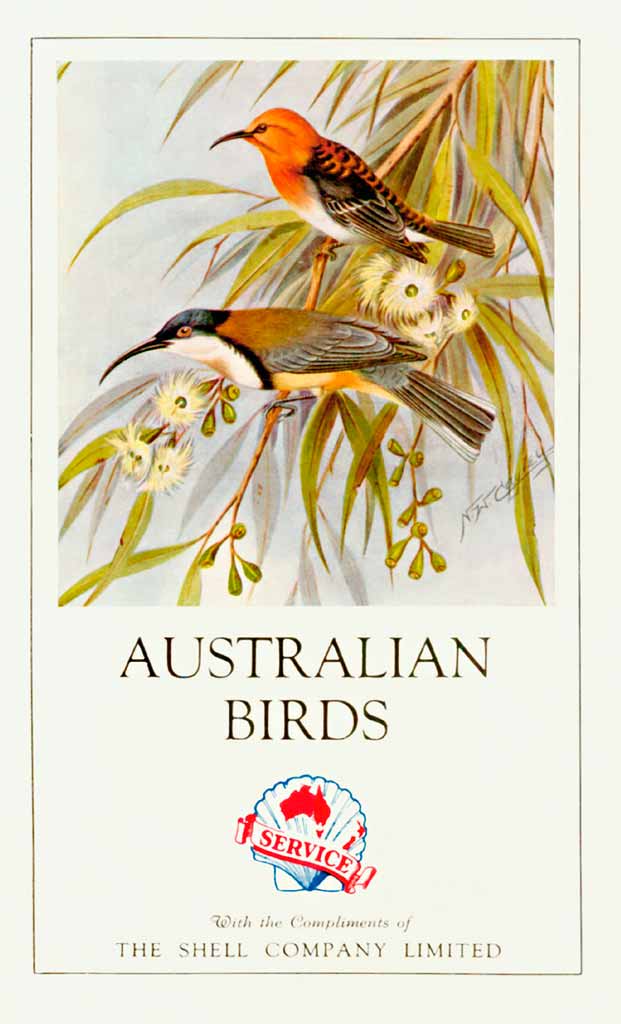

Neville William Cayley, Scarlet Honeyeater and Eastern Spinebill on title page of Australian Birds (1930)

The title page for Australian Birds, a 64-page booklet issued by the Shell Company in 1930, featuring several coloured illustrations of birds and eggs by Cayley. It came with the message: ‘Motorists! Wherever you go in search of your feathered friends, remember—“YOU CAN BE SURE OF SHELL”’.

Despite the Great Depression of the very first years of the 1930s, Cayley kept producing illustrations and text for books and Angus & Robertson kept publishing his work. As did other nations, Australia suffered years of high unemployment, poverty, low profits, plunging incomes, and lost opportunities for economic growth and personal advancement. Recovery began in 1932, but took some years. Still, what The West Australian called the ‘phenomenal output of books by Australian writers’ in 1930 continued into 1931, which was summarised by the newspaper as: ‘a year of difficulty, for the book-buying public, and of anxiety for the book-sellers’. Nevertheless, the article continued, it had been ‘a year of notable activity, on the part of the

Australian publishing houses’. It opined that: ‘Messrs. Angus and Robertson must count this a year of splendid achievement with such books in their list as … Neville Cayley’s “What Bird Is That?” ’.

In 1933 Cayley lost the extraordinary George Robertson. Robertson had been his great supporter and something of a father figure. The burly, bearded bookseller died in August of that year. Among the mourners at his funeral were ‘a large number of professional and literary men’, the tabloids reported. Nevertheless, a lone female, Mrs Mary Gilmore, was listed. So too was Ernest Frederick Crouch, Cayley’s second cousin, and Arthur Francis Basset Hull, Cayley’s colleague from the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales (RZSNSW) and the RAOU.

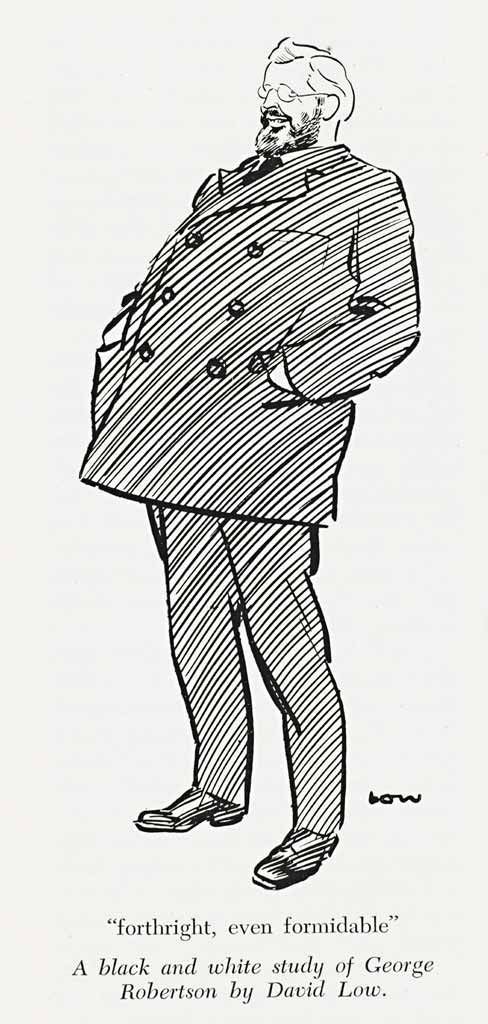

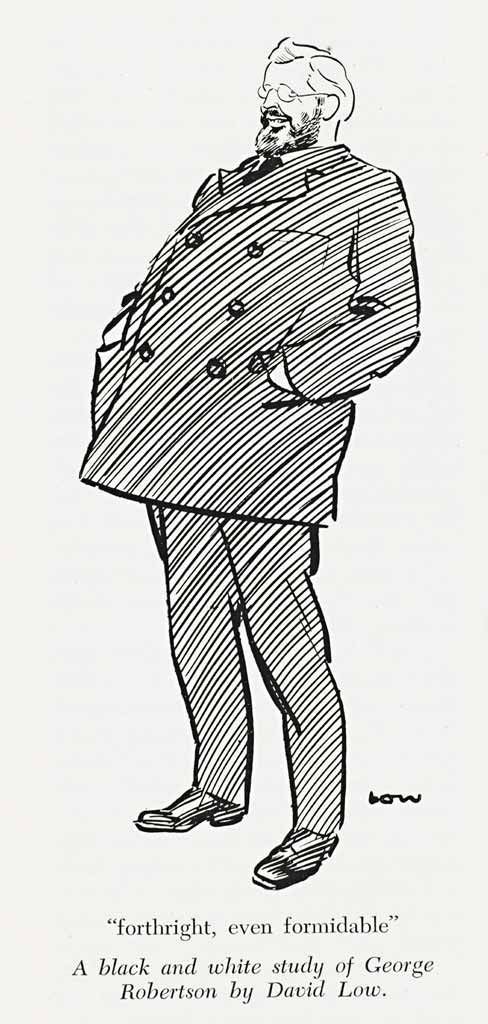

David Low, A Black and White Study of George Robertson 1955

A larger-than-life character, publisher George Robertson was a great supporter of Cayley and his firm Angus & Robertson published all of Cayley’s significant books, beginning with the ground-breaking What Bird Is That? in 1931.

As Cayley well knew, Robertson could be blunt, quick tempered and stubborn, but he was also generous: always ready to help a needy author financially and to publish a worthy book even though it would lose money. Robertson had been a visionary figure in the Australian book world and was held in high esteem by all who knew and worked with him. The Courier-Mail paid tribute to his bravery and influence under the wordy but apt heading ‘George Robertson. A Great Publisher; the Man Who Inspired the Mitchell Library and Gave Splendid Books to Australia’, continuing:

Imagine for a moment the early A. and R. books without him, the slapdash Banjo, the crude, irregular and disciplined Lawson; most of the serious books never written, simply because no other publisher would have risked the loss on them.

Robertson’s death was an enormous loss, but he had established a market for Australian writers, and his company, Angus & Robertson, carried on in the same spirit.

New technologies were making publication of colour less costly, a particular boon to a painter of birds. As early as Christmas 1930, The Sydney Mail produced what the advertisements claimed was one of its best issues ever. It was not only ‘rich in seasonable stories, articles and verse’, but displayed a good deal of colour, ‘the finest example of which is a really beautiful study of blue wrens in a golden wattle tree, from a painting by Neville W. Cayley’, which, it was predicted, would be cut out and treasured by thousands.

Advances in technology were also enriching the many talks given by Cayley. At the RZSNSW jubilee of 1929, held at David Jones, Sydney, the attendees ‘were asked to divide their attention between a ball, a bridge party and a series of brief lectures’, The Sydney Morning Herald reported. Most chose the former, but the zoological talks were praised. Alec Chisholm stirred the audience with his assertion that Moreton Bay, where he had recently investigated bird life, was far lovelier than Port Jackson, but was countered by another naturalist who pointed out that mosquitoes and sandflies inhabited the shores of the northern harbour ‘in deadly hordes’! Pictures of Australian snakes, butterflies and island birds:

were thrown on the screen by means of the epidiascope, a new instrument acquired by the society for depicting enlargements of pictures or objects in their natural colours. The method was outstandingly successful for showing a series of bird paintings by Mr. Neville W. Cayley.

Such technologies were a step forward from the old hand-coloured glass lantern slides that had been used previously to illustrate lectures.

Cayley was a regular presenter throughout the 1930s at the Gould League’s ‘annual hullabaloo’—as his comrade Chisholm put it—in Sydney. Cayley also often judged the bird-call competitions, at which acclaimed bird-call imitator Frank Clarke would give a performance of his art.

Cayley’s lecture schedule was gruelling and, according to Chisholm, he was always well prepared. His subjects were as varied as his audiences. In February 1933 he gave a talk on Australian birds to the Popular Science Club of the Australian Gas Light Company; in July he was on radio station 2FC (later Radio National) speaking on the harbingers of spring; in September he gave an address titled ‘Rambles in Birdland’ to a packed crowd at the Lyceum. At the latter, he fascinated the audience with tidbits of information about the lives of birds. As The Sydney Morning Herald reported, Cayley stated that observation of male blue wrens had cleared their reputation of having more than one wife, for, ‘It was now known that the various dingy-coloured females in attendance upon the brilliantly plumaged male were not wives, but were members of the previous brood’. (Cayley was correct about the helper fairy-wrens but it is now known that the female is far from faithful, visiting other males under cover of the pre-dawn gloom.)

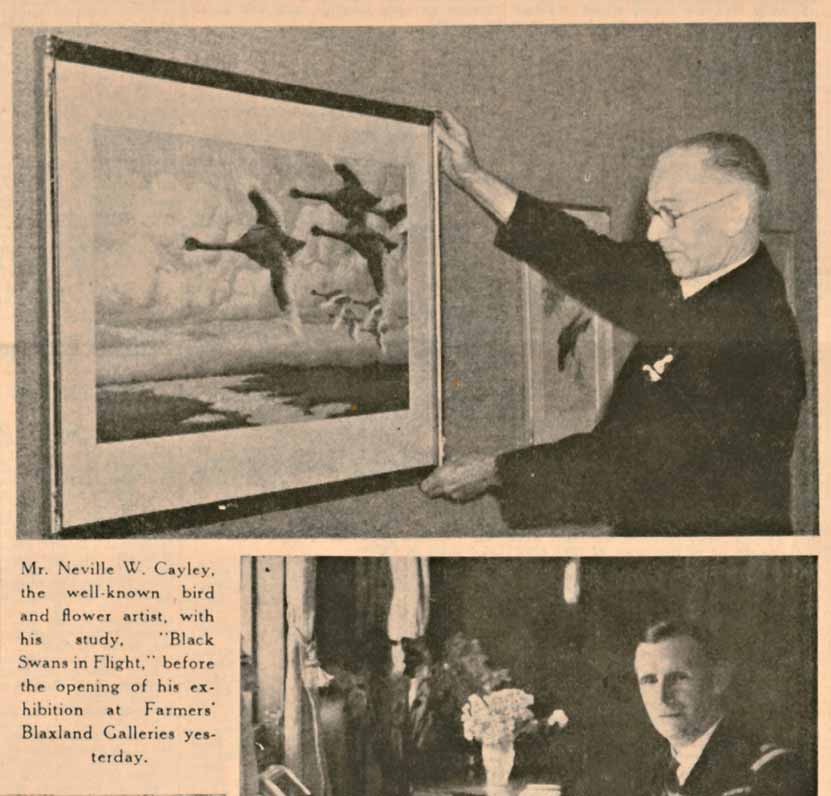

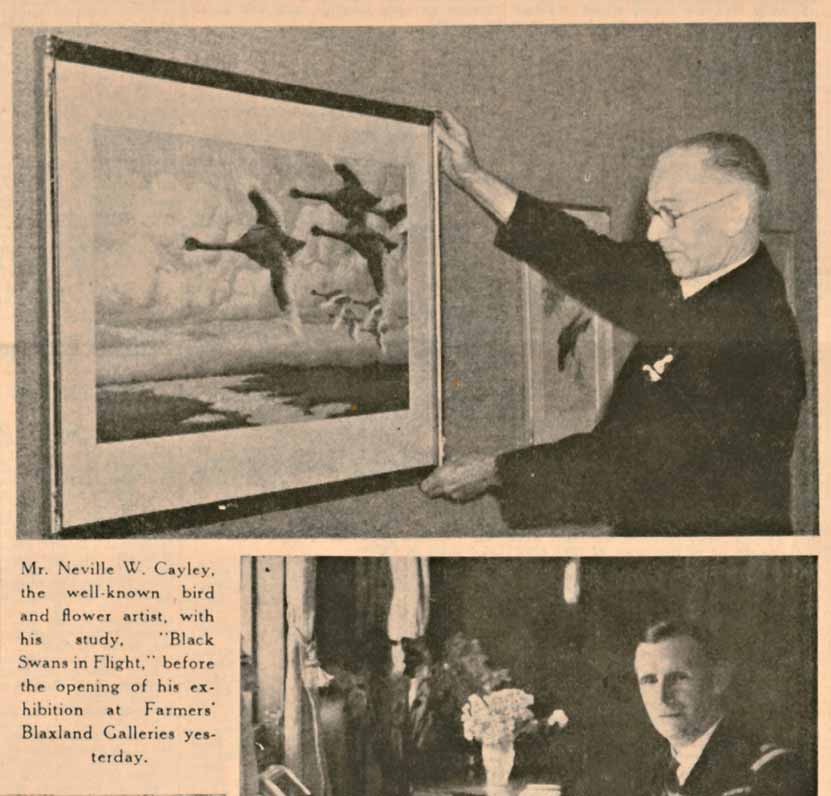

Neville William Cayley with his painting Black Swans in Flight, in The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 April 1938, p. 14

As well as illustrating and writing for books and newspapers, the Gould League and the scientific journal Emu, giving talks to groups and on the radio, and holding prominent positions in various learned societies, Cayley supplied illustrations for several exhibitions.

Never one to let an opportunity to correct commonly held misconceptions pass, Cayley went on to defend the musical abilities of the Australian songlarks and fieldlarks which were ‘comparable with the English skylark for richness and cadence of notes’ and stated his regret at the introduction and acclimatisation of foreign birds as most of them, he said, were ‘useless, and some mischievous and destructive’. The show was wrapped up with Clarke’s ‘splendid’ imitations of bird calls.

Although there was some overlap between the illustrations produced by Cayley for books, for the Gould League and the RAOU, and for his exhibitions, Cayley still painted volumes in the 1930s. He had seldom exhibited, but late that decade he had a steady schedule of exhibitions that put his work before the art-buying public. In April 1936, a collection of his paintings was on show in a gallery at David Jones’ George Street store, together with a few works by Cayley’s late father. Lady Gowrie, the wife of the New South Wales Governor, purchased a painting of a spinebill honeyeater feeding on native fuchsias and told the assembled press she had given What Bird Is That? to King George V for Christmas. The King was already in possession of a Cayley painting, Splendid Grass-parrakeet (Scarlet-chested Parrot), presented to him in 1932 by the members of the Avicultural Society of London, who were aware that the King possessed a live pair of the birds.

In September 1936 there was another exhibition and sale, this time in the Myer Emporium, Melbourne, where Cayley was billed as the ‘leading bird-artist of the Commonwealth’. Then, that November, the exhibition moved to the Myer Emporium in Adelaide. In April 1938 Cayley’s work was on show at the Blaxland Galleries, Sydney, and, that November, at the Gainsborough Gallery in Brisbane. From the latter, Queensland Governor Sir Leslie Wilson and his wife, Lady Wilson, purchased a watercolour of a pair of kookaburras, expressing, as The Courier-Mail put it, ‘pleasure at the excellent reproduction of the colouring of the birds and their life-like attitudes’.

While he was in Brisbane, Cayley took the opportunity to convince the popular Nature Lovers’ Society that they should federate with the Gould League. With his friend Will Mahony, Sydney cartoonist and black-and-white illustrator, he also visited the Brisbane Art Gallery (now Queensland Art Gallery) to view the works of their famous fathers: Neville Cayley and Frank Mahony, who had both been members of the Art Society of New South Wales and illustrators for The Picturesque Atlas.

The 1936 David Jones exhibition gave critics the chance to compare the work of Cayley and son. The father’s work was judged less fine and detailed than the son’s and his kookaburras ‘delightful, admirably summing up all the humour and almost Hogarthian vitality possessed by the Australian national bird’. Regarding Neville William, who no longer had aspirations to be a fine artist, if he ever had, a reviewer made clear that he was an ornithological artist, suggesting that his work was ‘so fine and detailed that it takes on the importance of science’ and that ‘For detail of plumage and colouring of some of the lesser known Australian birds these watercolours are invaluable’. The reviewer observed:

Occasionally the scientific side of his work is apt to oust the artistic. Some of the birds are woodenly grouped and obviously intended as a plate rather than a picture. However, in the majority there is sufficient charm of background to make them complete pictures in themselves.

Hanging in a Brisbane gallery in 1938, Cayley’s watercolours of birds and flowers received a favourable analysis from a fine art critic writing for The Courier-Mail, who thought that two stood out:

Perhaps the most outstanding studies in the collection are two action pictures of birds. In ‘Galahs in Flight,’ a flock of galahs are flying high across the Murrimbidgee Plains, their soft rose and grey feathers in contrast to the fleecy white clouds across a background of blue sky. The other, ‘Black Ducks on the Wing,’ shows, with minute detail, the rise from covey of two black ducks, while below them is the thin grass of the marsh.

The reviewer noted that Cayley’s work was of ‘special interest’ because it reproduced ‘so well the vivid colours and the soft tints of the birds of Australia’s bushlands’, continuing:

Mr. Cayley paints effectively crimson finches, pictorella finches, and red brown finches, each with their particular monotone. In several of his paintings of this type he has followed, it seems, the method of old Chinese artists, subjugating all surroundings to a surface tone … Red-backed fairy wrens resting on a clump of flannel flowers reproduce the vividness of the bird’s colouring and the soft depth of the flowers.

Although it must have cheered Cayley to have his artistry appreciated and his bird paintings purchased to be hung on walls, his interest remained scientific and educational. Unlike his father, he did not belong to any art societies. Instead, he was a prominent and active member of several scientific and conservation societies. He was a council member of the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales, its President from 1932 to 1933 and one of its first two Fellows.

He was also a member of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union and its President from 1936 to 1937; a Life Member of the Gould League of Bird Lovers and its Vice-President until his death; a member of the Wild Life Preservation Society of Australia; and a trustee of The National Park on the outskirts of Sydney, from 1937 to 1948.

Though most of Cayley’s energies were directed towards the world of birds, some involved the world of words. In 1936, he joined and was elected to the executive of the Fellowship of Australian Writers, founded by Mary Gilmore. At the time, his friend explorer and adventure travelwriter Charles Price Conigrave was one of several concurrent vice-presidents; the others included Dorothea MacKellar and Hugh McCrae. The fellowship held regular meetings and lectures, a Christmas party and an annual ball. Its members discussed such issues as the rising threat of fascism, censorship and the desirability of a literary fund. One of the fellowship’s goals was the promotion of Australian writing; in this the uniqueness of the Australian landscape was integral, so that Cayley was not alone in finding inspiration in nature. Miles Franklin, Dorothy Drewett and George and Dorothy Ashton were believed to be among Cayley’s associates in the fellowship. Franklin’s diary note for 17 August 1939 records a supper with Cayley and her good friend author Flora Eldershaw at a coffee house, after a meeting of the writers’ group.

W.S. Smith, Group Photograph of Members of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union c. 1921

Some of the members of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union at the organisation’s Sydney congress in 1921. Cayley is second from the left in the back row next to his great friend Keith (‘Lofty’) Hindwood, who is standing in the centre. Cayley’s other colleagues include Archibald Campbell, who is in the second row at right, and Dr John Albert Leach, third from the right in the front row.

Another of Cayley’s colleagues in the fellowship was Frank Clune, a writer of adventure travel books. At meetings, Clune gave talks on his travels across Australia, which Cayley no doubt would have enjoyed. On a visit to Clune’s house in about 1945, Cayley met George Boreham, a correspondent of book collector Father Leo Hayes. Ten years later, Boreham would remember that Cayley had arrived bearing a gift for Clune’s wife—‘an exquisite small painting of a bird’. Boreham was thrilled to be able to identify the bird immediately, as Microeca fascinans (Jacky Winter). ‘Are there two of us?’ Cayley said, thinking that he had met a like soul. Many years before, as a young man, Boreham had spent a considerable amount of time at the Australian Museum, organising his egg and nest collection. He had to admit to Cayley that ‘if it had been any other bird I would not have known its scientific name; just that one, of all I once learned, stuck in my mind’. Still, he was pleased that he had impressed Australia’s leading birdman.

In July 1933, on retiring after one year as President of the Royal Zoological Society, Cayley gave an address on parrots, the subject of his work in progress Australian Parrots: Their Habits in the Field and Aviary. He realised that he was not alone in his passion for parrots, stating that ‘scientists, bird-lovers, and tourists’ were ‘attracted by the beautiful parrots of Australia’. Having already completed books that included avicultural information on finches and budgerigars, which he hoped would bring ‘closer cooperation between ornithologists and aviculturists’ to advance the study of birds, Cayley was at pains to explain that he approved of captive breeding only in certain circumstances:

Unless a serious attempt is made to try and save the few species now on the verge of extinction it will be too late, and they will pass away without our knowing anything of their life histories. I wish it to be clearly understood that in advocating the breeding of parrots in captivity, I do so in the hope that it will be carried out under licence and in a purely scientific manner, not on a commercial basis.

For the past decade the ornithological fraternity had been transitioning from the time when the world’s resources, including its wildlife, seemed endless, to one in which there was increasing concern that certain birds, some once common, had become vanishingly rare. The collection of specimens had been an acceptable, gentlemanly hobby as well as the standard way to study birds. In the 1930s, it was obvious that there was a real need to learn more about the living bird and increasingly the collection of specimens was deemed desirable only for particular purposes. But old habits die hard, and there were bitter disputes that came to a head at an RAOU camp at Marlo in Victoria, at the mouth of the Snowy River, in October 1935. Cayley was among the 20 attendees from Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria. The New South Wales group included Cayley and his friend Keith Hindwood, businessman and renowned amateur ornithologist, as well as Charles Bryant, editor of Emu, and Noel Roberts, the editor of several Sydney and Newcastle newspapers.

The main activity at camp was a search for the rare and elusive Eastern Bristlebird, but the need for the restriction of collecting was a major topic of discussion. George Mack, from the National Museum of Victoria, got fed up with all the talk and provoked the majority by leaving the breakfast table to shoot a Scarlet Robin nesting on the edge of the camp. Mack had permits that allowed him to collect, but Scarlet Robins were already well represented in all the major institutions—he was simply thumbing his nose at the expense of the robin. The New South Wales contingent left in protest.

The Melbourne–Sydney divide had been evident from the establishment of the RAOU but, even though several Victorians were sympathetic towards the views of the Sydney contingent, for a time the debate around the ‘Marlo incident’ exacerbated the tensions. At the following year’s national campout the gathering discussed the proposition that ‘no collecting be permitted at camps’. After much debate, a compromise was adopted that allowed collection of novel birds and eggs, and only then with approval from others in the camp. A committee was formed to develop a consensus on the wider issue but they could agree only on the weak statement that the collector should be under obligation ‘to add to the sum of human knowledge’, and should not merely gather material for its own sake.

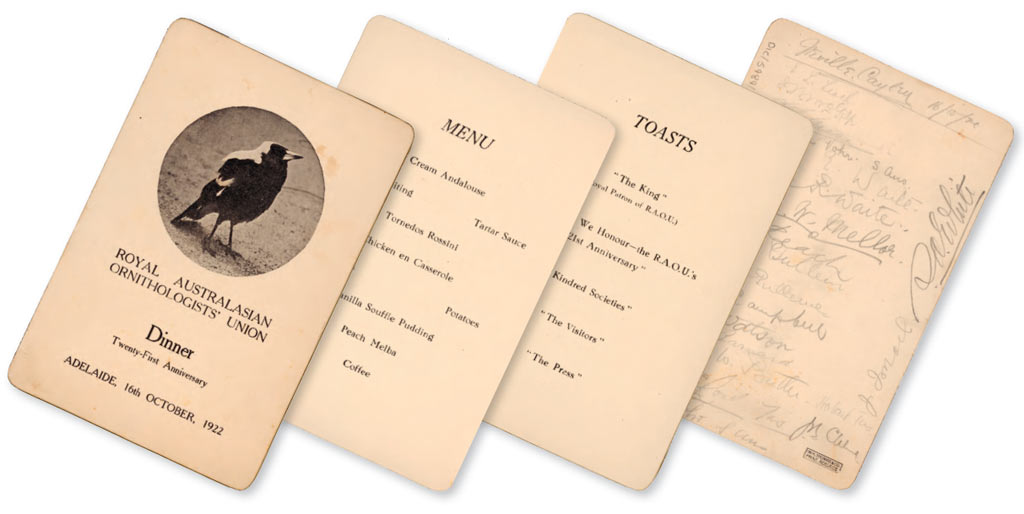

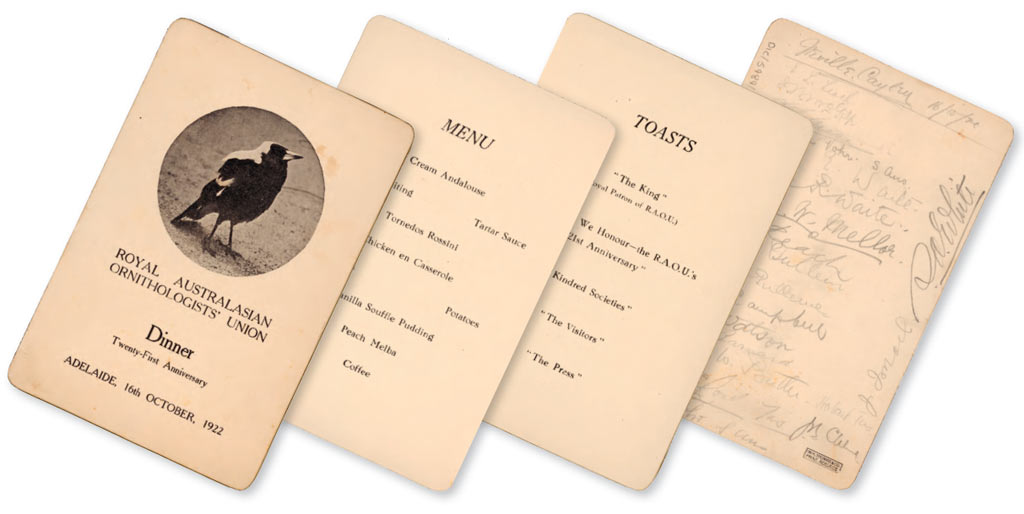

Menu for the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union Dinner, 1922

In 1922, the annual conference of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union was held in Adelaide, South Australia. It was the organisation’s 21st birthday and Cayley attended as the New South Wales representative. His signature tops the back page of the menu.

But the writing was on the wall whether the RAOU was prepared or not. In New South Wales, a month or so after the campout, police seized egg collections, data slips and related correspondence from the homes of several prominent ornithologists. Reports on the confiscations found their way into newspapers in several other states. Mr Chaffey, the New South Wales Chief Secretary, responsible for administering the Birds and Animals Protection Act, warned that ‘legal proceedings would be taken against persons found in possession of eggs of protected birds’ and that ‘the eggs would also be seized’. He went on:

any person having such eggs should send them to the Australian Museum without delay … With few exceptions … practically all native birds and animals were protected at present. Any person disturbing, hunting, or shooting any such species was liable to a penalty of £20.

Some members of the RZSNSW were raided and, consequently, the Minister gave a cautionary address to the society’s ornithological section, of which Cayley was the Chair. In response to the Minister’s warning, Cayley stated that the society did not condone the illegal collection of eggs and regretted ‘that the section should get the “backwash” of what had occurred’. He also defended his members, as The Sydney Morning Herald reported, telling the Minister that: ‘The men whose eggs had been seized were among the foremost ornithologists of the State, and their collections had been started long before collecting was made illegal’. Still, it was time for everyone to clean up their act. The days of unrestricted interactions with wild birds whether for hunting (sport), trapping (commerce) or hobby (aviary and cabinet collections) were on the wane.