Once the decision to proceed with the raid had been made the complete air operation was put under the control of Air Vice-Marshal TrafTord Leigh-Mallory cb dso, Air Officer Commanding No 11 Group of Fighter Command. At fifty years of age, Leigh-Mallory had considerable experience of command, having joined the Royal Flying Corps from the Army in 1916, holding various commands in that war and during the inter-war years. When World War Two began he commanded No 12 Group, Fighter Command which he continued to lead during the Battle of Britain. His immediate superior in 1942 was Air Chief Marshal William Sholto Douglas kcb mc dfc, who had been knighted for his services the previous year.

Leigh-Mallory and his staff gathered together a formidable number of squadrons with which to carry out the Royal Air Force's assigned tasks for 19 August. In total he had 48 squadrons of Supermarine Spitfires, four of which were equipped with the latest Mark IX, two with Mark VI, the remaining 42 having Fighter Command's main fighter aeroplane, the Spitfire Mark Vb and Vc. With very few exceptions these units would provide the essential air cover to the raid, including escort cover for light bombers plus escort for a planned attack by American B17 Flying Fortresses. They would also have to provide continuous protection for the ships and boats during the raid and their subsequent return to England in the afternoon and early evening.

For attacks against light and heavy gun positions and troops in and behind Dieppe itself and on the two headlands to the east and west of the harbour which dominated the harbour and town, Leigh-Mallory had eight squadrons of cannon-armed Hawker Hurricane lis, including two squadrons designated as fighter-bombers. These latter two units could carry either two 250 lb or two 500 lb bombs, one bomb carried under each wing. For heavier attacks, especially in use against well protected gun emplacements, and for initial smoke screening operations, he had three squadrons of Douglas Boston Ills from 2 Group, Bomber Command, plus a handful of Intruder Bostons from 418 and 605 Squadrons of Fighter Command. In addition he had two squadrons from Army Co-operation Command flying Bristol Blenheim IV bombers.

Both Leigh-Mallory and the Chiefs of Combined Operations needed to know instantly of any hostile developments inland from Dieppe. To keep the immediate rear areas of Dieppe under surveillance, four squadrons of North American Mustang Is of Army Co-operation Command were made available. The last units of his main force which were brought in at the last moment were one Hawker Typhoon Wing of three squadrons. One 'Jim Crow' Spitfire squadron was also brought in plus the usual air-sea-rescue units.

In total Leigh-Mallory had approximately seventy squadrons available to him for the raid. With 48 squadrons of Spitfires, including three from the USAAF, he had a far greater fighter force available than Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding had at any one time when he commanded Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain in 1940.

By the beginning of August 1942, the fighter pilots in Fighter Command were being led by many experienced air fighters. Most of the leaders of Leigh-Mallory's Dieppe squadrons were veterans of the Battles of France and Britain and the summer offensive of 1941. In these conflicts most of them had been junior officers or NCO pilots. Having survived to 1942, approximately fifty of the squadron or flight commanders at Dieppe had seen action in the Battle of Britain alone. The wing leaders too were all experienced, seasoned pilots of 1940—41.

Pat Jameson dfc had gained famed with 46 Squadron during the Norway Campaign in 1940 and had been one of only two survivors of the squadron when the aircraft carrier HMS Glorious had been sunk. Now he led the West Wittering Wing. David Scott-Maiden dfc led the North Weald Wing. He had been a classics undergraduate at Cambridge and had flown with two Auxiliary squadrons in 1940 winning the DFC in 1941. Commanding 54 Squadron he received a bar to his DFC in 1942. Minden Blake, like Jameson a New Zealander, won his DFC in the Battle of Britain. By mid-1942 when he received the DSO he had claimed at least nine victories. He led the Portreath Wing where his usual task was to range long distances across the western end of the English Channel to Brest and Cherbourg. Petrus (Dutch) Hugo, a South African, had already won the DSO, DFC and bar, having seen action in France and in the Battle of Britain, commanding 41 Squadron in late 1941. By the time he took over the Hornchurch Wing in July 1942 he had claimed some ten victories.

Eric Thomas dfc was the Biggin Hill Wing Leader. A pre-war pilot he too had fought over England in 1940, becoming a squadron commander the following year. In early 1942 he led one of the Eagle Squadrons. R. M. B. Duke-Woolley was a graduate from the RAF Cadet College at Cranwell. Having initially been a Blenheim pilot he later went on to single-seaters to fight in the latter stages of the Battle of Britain, winning the DFC. A squadron commander in 1941-42, he was awarded a bar to his DFC before taking command of the Debden Wing, amongst whom were members of the first Eagle Squadron comprised of American volunteers. Denys Gillam dso dfc was another Auxiliary pilot who fought in 1940 and had a string of victories by 1942 when he was given command of the first Typhoon Wing. Leader of the Tangmere Wing was P. R. 'Johnnie' Walker dfc. Another pre-war pilot he had seen action in France with 1 Squadron in 1940 gaining several victories. In 1941 he commanded 253 Squadron before becoming a Wing Leader. Included in his Wing was a Free French fighter squadron. Leading the first Polish Wing from RAF Northolt was Stefan Janus. He had gained several successes in 1941 and a DFC while a flight commander and later a squadron leader in two Polish squadrons.

These men, men from all over the world, and others like them were in evidence over Dieppe. In the air action that day would be Englishmen, Scots, men from Wales and Ireland, Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians, Americans, South Africans, and others from various British Colonies, including one from Ceylon and there was also a Maori. From Europe there were Free French, Free Belgians, Poles, Czechs; there were Norwegians and also a Danish pilot. All would contribute to the great air battle.

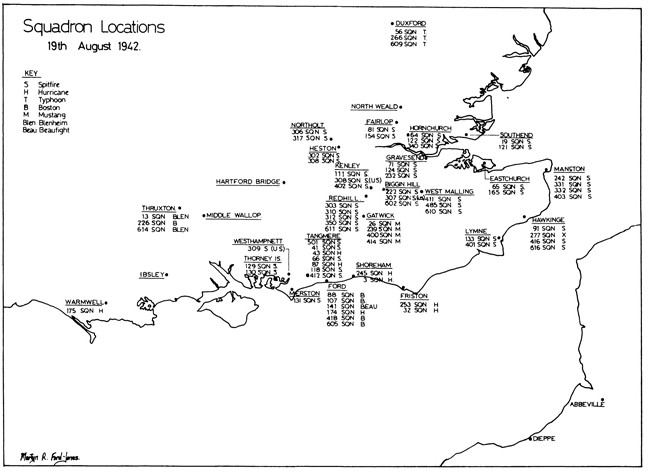

Trafford Leigh-Mallory grouped all his squadrons in southern England within a few days of 19 August. Those who were already strategically based in the extreme south were joined by others from either further north or from the west.

No 226 Boston Squadron of 2 Group, whose job it would be to lay smoke screens at Dieppe, was moved down from Swanton Morley, Norfolk to Thruxton near Andover on 14 August where it was joined by two Blenheim squadrons, 614 from MacMerry on the 15th, 13 Squadron from Odiham on the next day.The other two 2 Group Squadrons, 88 and 107, moved from their Norfolk bases at Attlebridge and Great Massingham on the 16th in great secrecy.

No 88 Squadron was sent off from Attlebridge to be based at Ford on 16 August, so we had time to settle in. The night-fighter squadrons normally based at Ford were in some measure moved out to make room for us. The airfield commander, Wing Commander Gerald Constable Maxwell - a kinsman of the Duke of Norfolk — was kindness itself and most efficiently made every provision for our stay.

Upon arriving at the wartime officers' mess or rather the sleeping quarters element, I was curious to know just why all the house bells were ringing incessantly. Upon tackling one of my young men about it, he said, 'Have a look at the notice, sir.' The house, as I remember, was an erstwhile girl's boarding school. And the notice read: 'If you need a Mistress, ring the bell'!

No 88 Squadron was located somewhere at the furthermost point on the airfield from the hangars, control tower etc: and so we had to more-or-less play boy scouts. However, everything seemed to work although my time was more spent in being scout master than being a pilot.

Wing Commander James Petty-Fry, OC 88 Squadron1

At Ford, near Littlehampton on the south coast of England, only a couple of crews remained of 605 Squadron who had just completed a move to RAF Hunsden on 14 and 15 August. The crews of two Bostons which remained, joined by two more who flew down from Bradwell Bay, would fly over Dieppe at dawn.

We of 226 Squadron were well prepared for our role. It was a good unit happily composed of aircrew from most parts of the Commonwealth plus one American whom we sadly lost at Dieppe. We considered ourselves something of experts in low level operations for which the Boston, at that time, was ideal. Squadron morale was high and not diminished by the fact that we were not particularly enamoured with the 'smoke' role.

Squadron Leader Graham Magill, 226 Squadron

For the Dieppe operation No 13 Squadron, which was based at Odiham in Hampshire, sent a detachment of aircraft, crews, maintenance personnel and catering staff to Thruxton in Wiltshire. This was necessary because the runways at Odiham were not long enough for a Blenheim IV to take off with a full load.

On the first occasion the detachment was very disappointed when the raid was called off at the last moment, but on the second occasion we were in position on 18 August and briefed that evening on the operational task which was to lay smoke along the cliffs of Dieppe to protect the attacking fleet from German coastal artillery.

Flight Lieutenant Eric Beverley, 13 Squadron

All eight Hurricane squadrons were grouped on the south coast. 175 Squadron stayed at its usual base at Warmwell but the other seven were all based right opposite Dieppe. 3 Squadron flew its machines down from Hunsden to Shoreham where it was joined by 245 Squadron from Middle Wallop. 32 Squadron moved to Friston, near Beachy Head, from West Mailing where it was joined by 253 Squadron from Hibaldstone. 43 Squadron's home was already established at Tangmere but 87 Squadron joined them there from Charmy Down, the squadron doing one or two 'beat-ups' of the aerodrome upon their arrival to impress the locals! 87 Squadron was a night fighter and night intruder unit but spent several hours hurriedly repainting their Hurricanes in order to have day camouflage for the Dieppe show.

Squadron Leader Denis Smallwood, Commanding Officer of 87 Squadron, was initially informed that his squadron would be required to participate in an air exercise on Salisbury Plain and it was not until all unit commanders at Tangmere were called to a special briefing that he knew anything about the plan for Operation Jubilee. 87 were highly delighted at the prospect and at the chance of taking part in a daylight operation.

August 18 - spent the day, apart from briefing, in converting the black night fighters to daytime camouflage. Paint everywhere -very rushed job. The briefing told us of the raid and of the withdrawal, timed for 1300 hours. I remember thinking, Tt will be interesting to read how it all worked out, in the next day's papers - if I am still alive!' A hot summer's day and we worked on until well into dark.

Pilot Officer Frank Mitchell, 87 Squadron

The eighth squadron, 174, moved along from its usual base at Manston to Ford where it squeezed itself among the Bostons, the Hurricanes and the Bristol Beaufighters of 141 Squadron whose home base this was. 141 Squadron were merely spectators of the Dieppe Operation but one crew would become involved later in the day.

No 174 Squadron, which was often up against enemy shipping, had its detailed briefing, studying a model of Dieppe which showed the squadron's assigned targets. Then early to bed ready for an early start.

Every Spitfire unit was squeezed into the south. Tangmere received 41 Squadron from Llanbedr and all the squadrons of the Ibsley Wing, 66, 118 and 501, while 412 Canadian Squadron flew in from Merston. 412 Squadron were on an air firing exercise at Merston when they were suddenly recalled to their home base of Tangmere on the 14th. This in itself suggested some big operation was imminent. On Monday the 17th, 412 were briefed for an escort mission to American B17s who were to attack Rouen. As the Canadians came from the briefing room they saw outside Lord Louis Mountbatten, who was head of Combined Operations, plus several senior Army, Navy and RAF officers, waiting to hold a conference. This together with the fact that several other squadrons had begun to arrive at Tangmere only went to heighten everyone's suspicions and raise the general excitement. Other squadrons had similar experiences, and some like 412 were then busily engaged in Channel patrols on the 18th, ensuring that enemy aircraft should not spy out the naval activity at several south-coast ports.

Meanwhile, 130 Squadron moved on the 18th, from Perranporth to share Thorney Island with 129 Squadron.

As far as I can remember after the briefing, the evening before Dieppe, everyone was told to go to bed and get some rest before the early start next day. Sergeant Pilot X went to a phone box and rang his wife at Perranporth saying he was on a big thing the next day and that he might not return. (He) . . was either court martialled or something and reduced to the ranks on the squadron's return to Perranporth for breaking security regulations.

Squadron Leader P. J. Simpson, OC 130 Squadron

No 133 'Eagle' Squadron and 401 Canadian Squadron left Biggin Hill to operate from Lympne while 416 Canadian Squadron and 616 moved from Martiesham Heath and Great Sampford to invade the privacy of 91 'Jim Crow' Squadron's base at Hawkinge which they shared with 277 Air Sea Rescue Squadron. One pilot of 416 Squadron, Sergeant John Arthur Rae, 'Jackie' Rae to thousands of TV viewers in the 1960's, spent the 18th flying Air Training Corps cadets on Air Experience trips in the squadron's two-seater Magis-ter. He made 21 such flights and was later to admit that had he known what was in store for him the next day he would not have been quite so keen.

RAF Manston was invaded by 242 Squadron and the two Norwegian Squadrons 331 and 332, all from North Weald and who comprised the North Weald Wing. They were joined by the Canadians of 403 Squadron who had been resting from operations at Catterick. Another squadron which was officially on rest was 602 at Peterhead in Scotland, but it flew down to Biggin Hill to join in the action. 303 Polish Squadron left its North Sea convoy patrol duties out of Kirton-in-Lindsay to move down to Redhill in Surrey where it was joined by the Czechs of 312 Squadron from Harrowbear and the Czech pilots of 310 Squadron, in from Exeter. Redhill was the base of 350 Belgian Squadron and 611 Squadron who made their visitors welcome.

West Mailing was visited, on 16 August, by the Canadians of 411 Squadron from Digby in Lincolnshire, New Zealanders of 485 Squadron from Kingscliffe in Northamptonshire and 610 Squadron from Lydham in Norfolk.

At West Mailing we found we were to form a 12 Group Wing with the New Zealand 485 Squadron and the Canadian 411 Squadron. Pat Jameson from Wittering was appointed wing leader; he told us that we would be based at West Mailing until the big show was over. Jamie flew off to various conferences at 11 Group, and although we had no official news, the security of the proposed operation was exceedingly bad, for it was common knowledge that the Canadians were to assault a selected point on the French coast. We were about to take part in Operation Jubilee, the disastrous combined operation against Dieppe.

Squadron Leader J. E. Johnson, OC 610 Squadron1

No 610 had left their convoy patrols and Jim Crow missions to fly at Dieppe. The pilots were a trifle taken aback when they found that West Mailing had not batmen but batwomen - WAAFS - who brought round the early morning tea. One enterprising pilot, on hearing the approach of his batwoman one morning, placed a 12 inch wooden ruler between his legs under the bedclothes, which formed quite a pyramid. The WAAF brought in his tea and appeared to take little notice before leaving the room. A few moments later, however, the door slowly opened slightly and two wide-eyed female faces gradually peered into the room!

Other squadrons came from further afield. 165 left Ayr in Scotland to fly to Eastchurch on 14 August while 222 also left Scotland, moving to Biggin Hill from Drem. 232 like 222 left its tedious convoy patrol duties and moved from Turnhouse to Gravesend.

Throughout the summer of 1942 No 131 County of Kent Squadron daily had been on operations over France so by 19 August the unit was at the peak of its efficiency. The squadron was located at Merston, a small grass airstrip and it comprised part of the Tangmere Wing then led by Johnnie Walker.

Wing Commander Michael Pedley, OC 131 Squadron

Other squadrons at Kenley, Biggin Hill, Gravesend, Southend, Fairlop, and North Weald stayed put. By the morning of the 18th all were more or less settled in even though some of the domesticarrangements were a trifle strained. Despite this everyone was keyed up. All were certain that something big was in the air and when the pilots and aircrews were finally called into briefing huts or rooms all knew they were in for a big battle.

Eighty-one Squadron at Fairlop were called to their parent station, Hornchurch, where they were briefed for the morrow. They returned to Fairlop and like many others went 'to bed early to be on the top-line in the morning which is awaited with great eagerness.5

At RAF Manston Wing Commander David Scott-Maiden dfc had all of his pilots, British and Norwegian, crammed into a briefing hut to give them a detailed run down on the raid. Scott-Maiden recalls that it was the first operation where it was essential to know everything about what the Army - Canadians and Commandos — and the Royal Navy planned to do and where the RAF fitted into the scene of operations. For the first time it was truly to be a Combined Operation.

The briefing contained that we were to maintain air superiority throughout the operation and regardless of opposition or cost to ourselves — ' . . . fight it out even if you are to remain there alone to the end.' Our Wingco, David Scott-Maiden, was one of few words and tremendous authority. It is amazing how words like that can arouse enthusiasm.

Major Wilhelm Mohr, OC 332 Norwegian Squadron.

This attitude reflects 332 Squadron's motto, 'Samhold I Strid Til Seier' — 'Stick together and fight until victory.'

The daring atmosphere about this particular operation, new to most of the air and ground crews I shall not try to describe. This was something new, a step into the future, a step of advance on the enemy, a step which demanded an all out effort on the ground and in the air. The briefing of the pilots followed its normal routine, but little was told to the ground crews until after the operations had started. However, the evening before, when all preparations had been done, I went round to the various sections of my squadron to see that they were all happy and to let them have an idea of what was coming. The ground crews were just as anxious as the pilots, and some of them too, not only pilots, didn't sleep too long that night. I must have been rather confident in my squadron, because I did after all sleep most of the night!

Major Helge Mehre, OC 331 Norwegian Squadron

602 Squadron moved from Peterhead, whence it had been withdrawn for a rest exactly a month earlier, to Biggin Hill on 16 August, to participate in Operation Jubilee. In order to keep our hand in, we organised a Rodeo or fighter sweep on the 17 th and 18th, the former proving somewhat abortive whilst the latter provoked enemy reaction and enabled me to destroy an FW190. Sadly we lost Flight Sergeant Gledhill, last seen going down in flames, but to our later joy heard that he was safe and well although a prisoner.

Squadron Leader Peter Brothers, OC 602 Squadron

At RAF Duxford, where the first Hawker Typhoon Wing was based, all three squadrons comprising the Wing, 56, 266 and 609, heard about the proposed raid on the 18th. They were called to briefing and addressed by the Duxford station commander, Group Captain John Grandy dso.

He told us in his usual blunt and cheerful style that a major operation was about to begin which would take our forces back to France for the first time since our hurried withdrawal in May 1940. For some of us who had taken part in that battle and the subsequent Battle of Britain this was a tremendous moment, but he went on to say that in view of the prevailing technical problems with our new Typhoons which were suffering engine failures and tail breakages at the time, all he would do on this occasion was to tell us that we could go on this operation if we wanted to, but if we thought the Typhoon wasn't ready he would go along with that.

The Wing Leader, Denys Gillam, then outlined the operations plan for the Duxford Wing to reinforce to West Mailing and from there, 'sweep' behind Dieppe at 10,000 feet to provide fighter cover over a sea-borne attack on the harbour and coastal defences. There was no hesitation at all - the Wing would go to Dieppe! Grandy was clearly delighted and the rest of the day was a whirl of preparation and repolishing of windscreens, running engines, checking guns and going over the briefing. The Wing was in fact at the end of a drawn-out and frustrating introductory period with its new Typhoons, and was more than ready to have a go.

Flight Lieutenant Roland Beamont, 609 Squadron

*

In the main, briefings were quite detailed, especially for the Boston and Blenheim crews whose first tasks would be to bomb and lay smoke in support of the troop landings. The Hurricane pilots too had detailed instructions. To help them, many prints of aerial photographs taken from a few days to a few hours before were studied in depth. Gun emplacements, machine-gun nests, strong points and gun batteries were pin-pointed - those that could be seen and identified - and their locations committed to memory. Other positions, it was hoped, would be spotted during the attacks. Timing had to be perfect. Height, speed and precise landfall must be closely watched. Return fire from the defences was expected to be heavy at first until — hopefully — the opposition was knocked out and then over-run by the Canadians.

Above the battle the Spitfires must protect and maintain a complete air umbrella over the town and the ships. Each squadron would be expected to patrol for at least thirty minutes in either squadron or wing strength, each group overlapping in order to retain complete mastery of the air. Failure to keep complete dominance in the air could cost the raiding force dearlv.

Losses in this expected air-battle were fully anticipated. In the planning and in the thinking, up to 100 RAF fighters was one figure given as an expected loss. Yet in this air battle, the battle in which Leigh-Mallory hoped his pilots would finally be able to give a hammer blow to the Luftwaffe; he hoped that at least the same number of enemy aircraft would be destroyed.

For the fighter pilots on the evening of the 18th, it was a time of high excitement. For months they had been trying to bring the Luftwaffe to battle by flying Sweeps, Circuses and Ramrod operations over France but quite often the Luftwaffe simply chose to stay on the ground. On this evening, however, everyone knew that the Luftwaffe could not possibly ignore this major confrontation.

We were very conscious of the fact that the enemy would surely react with every fighter aircraft within call . . . We were very tensed up at the reception in store for us, especially the numerical balance of forces in the air at that particular moment.

Wing Commander Michael Pedley, OC 131 Squadron

*

Opposing Leigh-Mallory's large fighter force on the morning of 19 August the Luftwaffe had two Jagdgruppen in France, JG2 Richtho-fen and JG26 Schlageter. These two units could muster a total of 190 serviceable Focke Wulf FW190 and 16 Messerschmitt Me 109 fighters, JG2 having 115, according to German strength returns. Luftwaffe bomber units which could be made available to attack both the landed troops and the convoy of ships, had a total of 107 aircraft in a serviceable state. Of these, Kampfgeschwader 2 (KG2) had 45, KG40 30 while KG77 reported 13 operational machines. Kustenfliegergruppe 106 logged 19 aircraft ready for action. Of these totals, 59 were twin-engined Dornier Do217s, the rest mostly Junkers Ju88s or Heinkel Hel 1 Is.

The scene was now set. Dieppe — Operation Jubilee - received the final go-ahead. On the night of the 18/19th, 237 little ships sailed from the southern ports of Portsmouth, Southampton, Newhaven and Shoreham, and steamed out into the Channel towards the French coast. Eight of these were destroyers, the Hunt class HMS Calpe being the headquarters ship from which Major-General H. F. Roberts mg, a Canadian, commanded the Military Force and Captain J. Hughes-Hallett rn commanded the Naval Force. Also on Calpe was a First World War Australian veteran airman, Air Commodore Adrian Trever Cole gbe mc dfc raaf who controlled the air operation from this forward vantage point. Cole, who was 47, had flown in the Great War in the Middle East and in 1918 had commanded an Australian fighter squadron on the Western Front. His main job on 19 August was to co-ordinate the squadrons flying above the raid.

There were several important RAF personnel aboard the control ship and on another destroyer HMS Berkeley, which was designated first rescue ship. On Calpe Acting Flight Lieutenant Gerald Le Blount Kidd rafvr was the air controller for the close support squadrons, while on Berkeley, Acting Squadron Leader JamesHumphrey Sprott rafvr was the controller of the low fighter cover squadrons. They were ably assisted by:

| Calpe | Corporal Turner (W.E.M.) from the Combined Signal School |

| Corporal Scoffins (W.O.P.) | |

| LAC Irwin (W.O.P.) both from Air Co-operation Command. | |

| Berkeley | Corporal Clark (W.E.M.) from 11 Group, Fighter Command. |

| Corporal J. Boulding, 26 Sqn (W.O.P.) | |

| LAC Billings, 26 Sqn (W.O.P.) both from Army Co-operation Command. | |

HMS Calpe left Portsmouth at 8 pm on the evening of 18 August. At 9.30 the convoy of ships sailed past Calpe who checked them before she steamed ahead again towards mid-Channel. At 1.15 a.m Calpe went through the gap in the German minefield that had been swept clear by minesweepers, the passage having been marked with marker buoys. Once through, Calpe turned to port, stopped and checked the ships again as they passed through the gap.

Three am on the morning of 19 August 1942 was the deadline. If the operation was going to be cancelled the order to do so would have to be issued by this time, for out across the Channel the landing craft were being prepared for lowering onto the grey/black sea. No cancellation order was made and the first landing craft were lowered at five minutes past three o'clock. Operation Jubilee was on!

Immediately orders began to be issued by Fighter Command Headquarters. At three minutes past 3 am, the first order was sent which required Bostons to attack and blind the 'Hitler' and 'Goring'1 gun batteries at 4.45 am, the time the troops would be approaching the beaches. Bostons of 107, 605 and 418 Squadrons received this first order.

At 3.06 am came order number two; Bostons to attack 'Rommel' at 5.09 am. 88 Squadron was given this job. And so it continued.

At 3.48 am a star-shell burned into the dark sky to the east of Dieppe. It was fired by a small convoy of coastal motor boats, escorted by three German submarine-chasers. Unknown to the attacking force this small convoy was approaching Dieppe harbour and had run into the 23 landing craft carrying No 3 Commando in towards the Yellow Beaches at Berneval and Belleville. There followed a brisk exchange of gunfire which lit up the night, caused considerable casualties amongst the Commando force and at least one of the German vessels was set on fire. Although the German sailors could see that it was a considerable force of British boats, to any watchers on the shore this action could just be yet another motor torpedo or motor gun boat attack on one of their coastal convoys. Surprise was still on the side of the attackers but only just.

However, nothing could stop Jubilee now. For the Canadians the Dieppe Raid was on. For the Royal Air Force their greatest air battle was about to begin.

1 All ranks are given as held in August 1942.

1 Wing Leader, J. E. Johnson, Ghatto & Windus 1956.

1 All strong points, gun batteries etc: were code-named by the Allied planners (see map).