2

The Case for Eating Less Salt

Population-wide reductions in sodium intake could prevent more than 100,000 deaths annually.

—Institute of Medicine, 20101

The stakes could not be greater.

Every year almost 800,000 people in the United States suffer a heart attack, and 365,000 die as a result of coronary heart disease.2 Heart attacks typically occur when a blood clot blocks one of the arteries that supply blood to the heart muscle. The lack of blood can kill muscle cells quickly, so it is critical to get to the hospital as quickly as possible after experiencing symptoms suggestive of a heart attack.

I recall well a beautiful July day at the Delaware shore when my wife felt unusual discomfort in her chest while riding a bike. We quickly rode back to a friend’s home and read some articles that described what heart attacks might feel like to women. Then, resisting the lure of the beach, we rushed to the hospital. Tests showed that Donna had suffered a mild heart attack, doctors installed two stents, and she has been fine ever since. If we had delayed, the outcome might have been very different.

A stroke is like a heart attack of the brain, but the stakes can be higher. The heart is just a dumb muscle—whereas the brain controls virtually every aspect of our life. Every year about 800,000 Americans suffer a stroke; 140,000 of them die as a result, while many of the rest suffer long-term debilitating effects.3

A stroke occurs because either an artery bursts (hemorrhagic stroke) or, in 87 percent of cases, gets clogged by a blood clot (ischemic stroke).4 When the blood supply is interrupted, brain cells start dying within minutes. Where in the brain a stroke occurs (and how severe it is) determines what the symptoms are. Symptoms vary greatly, but strokes may totally alter a person’s (and family’s) life. Victims can experience loss of balance, difficulty talking or breathing, incontinence, emotional changes, impaired thinking, memory loss, blurred vision, partial paralysis, inability to eat or get dressed, and numerous other problems.

Read how Jill Bolte Taylor, a brain scientist, explained in a TED talk what it feels like to have a stroke—based on her own experience when she was just 37:

I woke up to a pounding pain behind my left eye. . . . In the course of four hours, I watched my brain completely deteriorate in its ability to process all information. On the morning of the hemorrhage, I could not walk, talk, read, write, or recall any of my life.5

It turned out that the cause of Taylor’s stroke was a clot the size of a golf ball.

A ministroke, or transient ischemic attack (TIA) may sound less ominous, but the future consequences can be deadly. While a TIA only temporarily interrupts the blood flow and does not cause permanent damage, it signals a greater chance of having a major stroke: one out of three people suffering a ministroke go on to have major one within a year.6

Fortunately, medical advances and healthier lifestyles have led to a remarkable 75 percent reduction in the incidence of stroke deaths since 1968 despite the soaring rate of obesity, a major risk factor; between 2013 and 2015, however, stroke incidence inexplicably ticked up.7 Perhaps the influence of obesity is finally making the impact that some researchers have been predicting for years.

Early Research on Salt and Blood Pressure

More than a hundred years ago, two French researchers—based on their study of a handful of patients—were among the first to contend that high salt intake was a major cause of hypertension, though they blamed the chloride half of sodium chloride, not the sodium.8 The Journal of the American Medical Association acknowledged that research, but opined, notwithstanding the meager amount of evidence at the time:

We can not dispense with the use of salt. . . . Its usefulness to the average individual in health and to the population generally can not be questioned. It would be an interesting calculation how much the world’s progress is due to salt and how our present civilization could really exist without this important food preservative.9

(Note that JAMA conflates using less salt with eliminating it entirely.)

Though the French research was greeted with skepticism, around 1920 Frederick M. Allen and James W. Sherrill at the Psychiatric Institute in Morristown, New Jersey, tested salt-restricted diets anew. Those diets, made as palatable as possible, contained as little as 200 mg of sodium per day, far less than the 3,400 mg in today’s average American diet.10 Allen and Sherrill confirmed that patients with hypertension could tolerate those extremely low-sodium diets even over several years. The diets lowered blood pressure in 70 percent of the patients, including to normal levels in one out of five. Box 2.1 provides recent numbers on sodium, blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease, which includes hypertension, coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke, and other disorders.11

The concept of using a low-sodium diet to treat hypertension—which was called “malignant hypertension” because it was as deadly as the most untreatable cancers—did not really capture the attention of doctors or the public until 1939.12 That’s when Walter Kempner, a German physician and refugee working at Duke University, started testing a diet containing nothing but rice, fruit (or juice), and sugar plus some vitamins and iron to treat potentially fatal kidney disease and hypertension. The diet was extremely low in sodium, fat, and protein—as well as in taste and variety. Those were the days before antihypertensive medicines, and the Kempner Rice Diet, as it became known, was virtually the only treatment for hypertension. It simultaneously reduced heart size, cleared up damage to the retina, and improved electrocardiograms. The New England Journal of Medicine editorialized that “Kempner’s own therapeutic results are little short of miraculous.”13 Sixty-five years later, a review in the Journal of Electrocardiology concluded that the diet was effective “simply beyond belief.”14

Unfortunately, not all physicians embraced Kempner’s dietary treatment. When Kempner spoke at a 1946 meeting of cardiologists at the New York Academy of Medicine, some doctors doubted his findings and even accused him of exaggerating and falsifying his findings.15 Another problem was that not all of his patients enjoyed dining on the boring, austere diet. The Rice Diet was so restricted and unpalatable that Kempner—whose personal predilection for questionable behavior-modification methods might have distracted from his scientific achievements—actually beat some of his patients to get them to stick with it. (Kempner said in a court deposition, “I have whipped people in order to help them and because they say they want to be whipped.”)16 To increase compliance, Kempner allowed a more varied diet as his patients’ blood pressure declined.

*As I discussed in chapter 1, after appropriate adjustments, actual sodium intake is closer to 4,000 mg per day. See note 11 for box 2.1 sources.

The Rice Diet, or more palatable versions of it, reduced blood pressure by a remarkable 25 percent or so in about half the patients.17 Adding salt to that diet, as researchers at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons discovered, generally negated its effect, confirming that salt was the culprit. But as one physician said, and Kempner acknowledged, the diet “imposes such hardship upon the patient and so much difficulty in control as to make it virtually impracticable for general use.”18 By the late 1950s and 1960s, however, the availability of antihypertensive drugs relieved the need for the Rice Diet.

Animal research in the early 1950s shed more light on the effect of sodium and potassium on hypertension. With humor in medical journals being rarer than a two-headed giraffe in the wild or a zoo, it was amusing to read an article written by two hypertension experts, George R. Meneely and Con O. T. Ball of the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine:

For reasons probably not even known to himself, one of us developed at that time a curiosity about the long-term effect of added sodium chloride in the diet. . . . We had in mind the possibility that excess salt might manifest itself as a source of degenerative disease, nature unspecified. Our minds were open, even perhaps blank.19

Those researchers put large numbers of laboratory rats on “diets” that contained sodium chloride in levels ranging from toxically low to toxically high, with or without potassium chloride. They found, now unsurprisingly, that higher-sodium diets raised the rodents’ blood pressure. Potassium negated some of the effect of the sodium. Their important findings helped pave the way for similar research in humans.

Animal research also shed light on why some people are more susceptible to developing high blood pressure than others. In the 1970s, Lewis K. Dahl and Martha Heine, at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, New York, transplanted kidneys from rats that did not develop high blood pressure into rats that did.20 The result? The previously sensitive rats did not develop high blood pressure. Likewise, when the kidneys from susceptible rats were transplanted into resistant rats, those rats did develop high blood pressure. Clearly, assuming that the kidneys in rats and humans behaved similarly, our genes could have a dramatic effect on our chance of developing hypertension.

Animal research like Dahl and Heine’s, which used highly inbred laboratory rats, led many researchers to think that people were either sensitive to or resistant to salt’s effects on blood pressure. In fact, though, unlike those specially bred rats, people display wide variation in sensitivity.21 Some people—such as African Americans, those with hypertension, and elders—are especially sensitive. And some lucky people go through life with normal or even low blood pressure, with a high-sodium diet and other factors posing little problem. Most other people have intermediate sensitivities. In one striking example, in the prefecture of Akita in northern Japan, several decades ago average sodium consumption was a sky-high 10,000 mg per day.22 Thirty-nine percent of people (average age 45) were hypertensive—but the majority was not. Researchers are currently trying to understand the genetic determinants of salt sensitivity in order to identify people at high risk of hypertension and strongly encourage them to lower their sodium intake as soon as possible.23

Humans are much more closely related to apes than rats, which suggested studying the effect of salt on blood pressure in chimpanzees. In one failed experiment in the United States, the chimps involved were accustomed to consuming high-sodium biscuits providing 2,400 to 4,800 mg of sodium per day. When researchers tried giving the chimps low-sodium replacements, the animals refused to eat the biscuits and lost weight. The chimps ultimately won the battle and resumed enjoying their customary high-sodium diet.24

The researchers went back to the drawing board and found a colony of chimpanzees eating a natural, low-sodium diet at a research center in Gabon.25 They gradually increased the sodium content (up to 6,000 mg per day) in the animals’ diet for 20 months. As expected, the animals’ average blood pressure soared. As earlier studies had shown for humans and rats, some chimpanzees experienced large increases in blood pressure, some had smaller or even no increase, but on average their blood pressure rose steadily and dramatically. When the chimps were returned to their original low-sodium diet, their blood pressure gradually decreased to the original level.

Small, but interesting, studies on hunter-gatherer tribes added to the case that a high sodium intake boosts blood pressure and the risk of cardiovascular disease. Many thousands of years ago most humans consumed very little sodium, and that was the case for our primate and earlier ancestors going back millions of years. Today, most humans consume a high-sodium diet. But a few communities, such as the Yanomami Indians I mentioned in chapter 1, have barely been touched by our style of civilization and still consume ultra-low-sodium diets. The Yanomami consume less than one-tenth as much sodium as Americans.26

Strikingly, the Yanomami have much lower blood pressure, averaging only around 95/63 mm Hg, than young and middle-aged Americans, who average over 120 mm Hg systolic.27 (See box 2.2 for more about blood pressure: how our bodies react when our sodium intake changes, how our blood pressure responds, and how blood pressure is measured and monitored.)28 Equally striking, unlike in most Americans, the tribe members’ blood pressure does not rise with age. That phenomenon has also been observed in other isolated indigenous populations from South Pacific islands to the Kalahari bush in southern Africa.29 In one such community in New Guinea, sodium consumption was about 400 mg per day. Judging from blood pressure measurements and electrocardiograms, “only 3 per cent of males over the age of 40 . . . were hypertensive in contrast to 20 per cent of middle-aged American men. . . . Heart disease was rare if not absent.”30 That doesn’t mean salt was the only factor—more physical activity and dietary fiber, little obesity, less animal fat, and other lifestyle differences also were at play. But judging from the medical evidence—and the fact that those populations are not tempted by nearby McDonald’s and IHOP restaurants or canned soups and bags of chips—the lack of salt likely was a significant factor.

Also consider the Tsimane tribe in the Bolivian Amazon. It was more acculturated than the Yanomami and probably consumed more sodium.31 Nevertheless, their blood pressure rose much less with age compared to people in industrialized countries. Moreover, the prevalence of hypertension in people over 70 was only 8 percent in men and 27 percent in women compared to about 70 percent or more among older Americans.32

One basic question is whether hunter-gatherers are simply genetically resistant to the effects of salt on blood pressure. We can glean answers from instances in which they consume more salt or move to urban areas rife with processed foods, motor vehicles, cigarettes, and other accoutrements of modern life. In some cases, such as Easter Islanders who moved to South America and rural Zulus who migrated to African cities, the migrants had more opportunities to consume processed foods. Their blood pressure rose.33

Figure 2.1

Blood pressure categories. Source: Reprinted with permission (https://www.heart.org/-/media/files/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/hbp-rainbow-chart-english-pdf-ucm_499220.pdf). © American Heart Association.

Scientists also have compared communities that had access to salt or used saltwater in cooking to nearly identical communities that did not.34 One study focused on two rural communities in Nigeria that had similar diets and lifestyles. But the community that had access to salt from a salt lake had a higher sodium intake and higher blood pressure than the other.

Another study examined six isolated tribes with similar lifestyles in the Solomon Islands, a thousand miles northeast of Australia. In five of those tribes sodium consumption was under 700 mg per day, one-fifth what Americans ingest. People in those tribes were healthy overall and had “an almost total lack of coronary heart disease.”35 The one exception was a tribe that cooked vegetables in seawater. They had higher blood pressure than the other groups. Such studies provide strong evidence that the tribes’ health status is due more to the scarcity of salt than to genetics.

Of course, all of that ethnographic research does not prove that salt causes high blood pressure and heart disease, but the findings are certainly consistent with that hypothesis.

As those early clinical, animal, and ethnographic studies fostered concerns about the healthfulness of salty diets, more and more scientists and public health officials began calling for lower-salt foods. That spurred a counteroffensive from a few scientists and food industry officials who called for more evidence that lowering salt would be safe before any public health advice was issued or any regulatory actions taken. Public health action was delayed while a wide variety of increasingly sophisticated studies have been conducted to investigate the benefits and safety of lowering sodium consumption.

Key Research Supporting Lower-Sodium Diets

Controlled, human studies were one type of research needed to establish the relationship between sodium and blood pressure. Scores of studies have now been conducted in which blood pressure was monitored in people who were given different amounts of sodium for several weeks or months.

One of the early, well-designed experiments was done in England in 1989 with 20 patients who had mild high blood pressure.36 Graham A. MacGregor, a hypertension expert (more about him later), and his colleagues then at the St. George’s Hospital Medical School in London trained their patients how to eat a diet very low in sodium; to help achieve those low intakes, the researchers gave the patients salt-free bread, margarine, and certain other foods. After one month on the diet, the participants entered a new three-part phase during which researchers gave them pills to bring their sodium intakes to 1,150, 2,300, or 4,600 mg per day. Then, after one month at a particular intake level, the participants were switched to one of the other two levels; and after another month they were switched to the third level.

The initial results of the London study showed that going from a low-sodium intake to a mid-sodium intake boosted blood pressure by 5 percent. The high-sodium intake boosted their blood pressure another 5 percent. After one year, most of the participants pretty much stuck to the low-sodium diet, averaging 1,240 mg daily, and continued to have the same reduced blood pressure. The researchers said that patients found that “after 3–4 weeks of the diet, high-salt foods taste unpleasant and for many patients become unpalatable.” Blood pressure in 16 of the 20 patients was low enough for them to stop taking antihypertension drugs, though more recent, stricter guidelines would recommend that some of them take drugs on top of the low-sodium diet.

The DASH–Sodium Intervention Diet

The best and most influential of all the clinical studies on salt and blood pressure is the DASH–sodium intervention trial, which was conducted by researchers at Harvard Medical School, Johns Hopkins, and other institutions.37 DASH (short for Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) was a randomized placebo-controlled trial (RCT), the “gold standard” of biomedical research. Such studies can determine cause-and-effect relationships, whereas most other research, such as observational studies that follow large groups of people over many years, can only identify associations.

DASH’s primary developer was Frank M. Sacks, now a professor of cardiac disease prevention at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. It grew out of two studies he conducted in the early 1970s, before entering and during medical school, on blood pressure and cholesterol levels in young adherents to a macrobiotic, largely vegan diet (a diet that Sacks himself then ate). Both studies found the vegetarians to be in far better health than the control groups of typical Americans. For instance, the vegetarians’ average blood pressure of just 106/60 mm Hg was much lower than in most young people in the United States.38 Sacks said, “That gave me the dietary-patterns concept that I used a couple decades later to design the DASH diet and study.” Having confirmed the benefits of eating a healthy, mostly vegetarian diet, he led the DASH–sodium trial, in which healthy and ordinary non-vegetarian diets were tested at three levels of sodium.39

A key strength of the DASH–sodium trial is that the researchers provided the 412 participants—who had either slightly elevated blood pressure or hypertension—all of their meals and snacks. People were randomly assigned to eat either a control diet similar to what the average American eats or the DASH diet, which is higher in potassium-rich fruit and vegetables, calcium-rich, low-fat dairy products, fiber-rich whole grains, fish, lean poultry, and nuts. Versions of those two diets were prepared with low, medium, or high (typical of the American diet) levels of sodium: 1,500 mg, 2,500 mg, and 3,300 mg for people eating a 2,100-calorie diet. Sodium was increased or decreased proportionately for people who ate more or fewer calories. Participants ate their specified meals with each sodium level for 30 days, long enough for their blood pressure to largely adjust to the diets. The researchers measured the participants’ sodium intakes using the most accurate method available—24-hour urinary excretion—and their blood pressure.

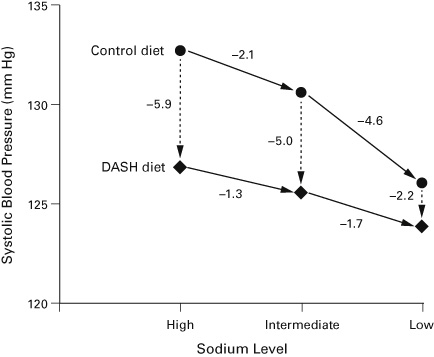

Figure 2.2 summarizes the exciting DASH–sodium results. The broken vertical arrows show that when people switched from the control diet to the DASH diet their blood pressure declined by 2 to 6 mm Hg, depending on the sodium level. That indicates one benefit of eating an overall healthy diet, rich in dietary fiber, potassium, and other nutrients and low in saturated fat, cholesterol, and sugar.

Furthermore, the solid arrows show that when people reduced their sodium intake from the high to the low level their systolic blood pressure dropped by 6.7 mm Hg (control diet) or 3 mm Hg (DASH diet). Lowering sodium from 2,500 mg to 1,500 mg (1,000 mg drop) provided a disproportionately greater benefit, especially for people on the control diet, than lowering sodium from 3,300 mg to 2,500 mg (800 mg drop).

Figure 2.2

Changes in systolic blood pressure on the DASH and DASH–Sodium diets at three sodium levels. The “High” sodium level is 3,300 mg per day, “Intermediate” is 2,500 mg, and “Low” is 1,500 mg based on a 2,100-calorie diet. The numbers show the reductions in systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) that occurred when going from one sodium level (solid horizontal arrows) or diet (broken vertical arrows) to another. (Diastolic blood pressures showed a similar pattern.) Source: Illustration by J. Bach, CSPI. Adapted from Sodium Collaborative Research Group, “Effects on Blood Pressure of Reduced Dietary Sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet,” New England Journal of Medicine, 344 (2001): 3–10.

The DASH researchers also reported the following results (not shown in the figure):

- • Blood pressure declined more in African Americans than in whites.

- • Blood pressure declined more in people with than without hypertension.

- • In participants with hypertension, the low-sodium version of the DASH diet was as potent as treatment using one or two blood pressure–lowering drugs (doctors often prescribe multiple drugs).

- • The biggest benefit—a whopping 15.1 mm Hg average decrease in systolic blood pressure—was seen in hypertensive African American women older than 45 who switched to the healthy, low-salt diet.

- • The decrease in people over 45 without hypertension, and who were eating a typical American diet or a DASH diet, was twice as great as in younger adults.40

DASH–sodium was a landmark study that demonstrated decisively that consuming less sodium lowers blood pressure. Richard Cooper, a cardiovascular researcher at the Loyola University Parkinson School of Health Sciences and Public Health in Chicago later called DASH “the most beautiful piece of data I’ve seen in my whole life.”41

The DASH authors stated that their study “should settle the controversy over whether the reduction of sodium has a worthwhile effect on blood pressure in persons without hypertension” (emphasis added). The study was so persuasive that the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has publicized the DASH diet widely, including with a free booklet that is available on its website.42 Numerous privately published books, including cookbooks, based on the DASH diet are available at bookstores or online.

Fortuitously, the DASH–sodium trial provided a real-life opportunity to gauge what people thought of the taste of lower-sodium foods. Were they as off-putting as some people believe? Surprisingly, the participants liked the intermediate-sodium foods more than the foods with smaller or larger amounts of sodium.43 And the low-sodium diet tasted just as good as the high-sodium diet typical of how Americans now eat. So much for the argument that people would never stick to a lower-sodium diet!

More Trials and Meta-Analyses

Further strengthening the evidence that higher sodium intakes increase blood pressure, in 2002, a year after DASH–sodium was published, Feng J. He and MacGregor in London performed two “meta-analyses” of well-done RCTs.44 A meta-analysis combines the results of several similar studies to increase the ability to detect health effects of a diet, chemical, or drug. But the devil is in the details: results can vary widely depending on the studies included.

One of the He–MacGregor meta-analyses included 17 trials involving people with hypertension; the second included 11 trials of people with normal blood pressure. In people with hypertension, a 1,800 mg per day decrease in sodium led to a 5 mm Hg decrease in systolic blood pressure. Among people with normal blood pressure, a similar drop in sodium consumption led to a 2 mm Hg decline in systolic blood pressure. The researchers estimated that a long-term 1,800 mg reduction in a population’s sodium intake45 (more than a 50 percent reduction for Americans) reduced blood pressure in people with hypertension enough to prevent 14 percent of stroke deaths and 9 percent of deaths from coronary heart disease. Among people with normal blood pressure, they estimated that a sodium reduction of that magnitude would reduce stroke and coronary deaths by about 6 percent and 4 percent, respectively.

The most finely detailed and recent meta-analysis was undertaken by researchers in Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and Japan.46 They incorporated the results of 133 previous studies with more than 12,000 participants. The results were just as expected. They found a strong dose–response relationship: the larger the reduction in sodium the larger the fall in blood pressure. The effects of a major reduction in sodium were strongest in people with high blood pressure (a decline of almost 3 mm Hg systolic), but trivial in those with normal blood pressure (under 120/80). Almost every segment of the population benefited from consuming less sodium, with the blood pressure of women, blacks, and older adults dropping more than men, whites, and younger adults. For example, the effect of lowering sodium by about 1,150 mg was about 10 times as great in adults between 56 and 65 years old (–3.88 mm Hg systolic) as in those 35 and younger (–0.39 mm Hg). Also, the effect of that same reduction in sodium intake in blacks (–4.07 mm Hg) was two-and-a-half times greater than in whites (–1.60 mm Hg). And showing that it takes a bit of time for blood pressure to adjust to lower sodium levels, larger decreases were seen in tests lasting two to four weeks than in shorter ones.

Those single-digit reductions in blood pressure may seem small—and for a given individual they would be modest—but they would yield a huge health benefit for the population at large. Nancy Cook, a biostatistician and epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, and her co-workers estimated that an average decrease of just 2 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure in the entire American population would lead to a 17 percent decrease in the prevalence of hypertension, a 6 percent decrease in the risk of coronary heart disease, and a 15 percent decrease in the risk of stroke. That “small” decrease would prevent an estimated 67,000 heart attacks and 34,000 strokes and TIAs every year.47

Another illuminating trial looked at the sodium issue from a different perspective. It compared whether treating mild hypertension with lower sodium consumption or drugs was more effective. Lawrence J. Appel, a professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and a long-time adviser to the American Heart Association, led the Trial of Nonpharmacologic Interventions in the Elderly, or TONE.48 As the name suggests, TONE was done in people 60 to 80 years old. The participants who were counseled to consume low-sodium meals and then taken off their blood pressure medication succeeded in dramatically lowering their sodium intake from 3,300 to 2,300 mg per day. After more than two years, not only did their average blood pressure decline (in the absence of drugs), but also many participants were able to stay off their meds. They also experienced fewer headaches and cases of angina (chest pain that might indicate heart disease), though the latter was not statistically significant.

Salt and Blood Pressure in Children

Many parents wonder whether diets high in sodium pose a problem for their young children, even though the risk of heart attacks and strokes may be decades away. That is a good question, considering that most kids’ diets are as bad as their parents’ and are certain to promote heart attacks and strokes when they grow up. Almost half a century ago, Edward D. Freis, a prominent hypertension expert at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Washington and Georgetown University School of Medicine, urged parents not to accustom their infants and older children to salty foods.49

In 1983 MacGregor wrote, “It may be that . . . hypertension becomes established in childhood rather than in early adulthood as thought previously.”50 Twenty-seven years later, with salty diets still no less a problem, Jane Henney, a former commissioner of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) who chaired an Institute of Medicine committee on lowering sodium intakes, said, “High blood pressure is a progressive condition that can begin to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease even in childhood.”51

The CDC found that about 4 percent of children 12 to 19 years old (1.3 million of them!) already have hypertension.52 Another 10 percent had higher-than-desirable blood pressure, but not rising to the level of hypertension. Children with higher blood pressure tend to have higher blood pressure as adults.53 (It’s a mystery why the percentage of adolescents with hypertension dropped by almost half between 2001 and 2016, a time of rising obesity and constant sodium intake.)54

Several interesting studies shed light on the impact of sodium on blood pressure in infants and children; one of the most revealing was begun in Holland in the 1980s.55 Its design was simple: Researchers randomly divided a group of 476 newborn babies into two groups. They gave 245 babies a normal-sodium diet including both formula and solid foods, while 231 babies ate a similar diet but with one-third as much sodium. After six months the low-sodium diet led to a 2.1 mm Hg lower systolic blood pressure.

Fifteen years later, the Dutch researchers were able to track down about one-third of the children. They found that all those years later the difference in blood pressure persisted. The infants who consumed a low-sodium diet grew into teenagers who presumably also consumed a lower-sodium diet and whose systolic blood pressure was 3.6 mm Hg lower than the children in the control group.56 That indicates the value of protecting children with a low-sodium diet from infancy. Fortunately, companies stopped adding salt to infant foods in the 1980s. But after children graduate to regular foods, their sodium intake soars. A study led by CDC scientists found that in 2015 a shocking 84 percent of 43 toddler dinners or meals were high in sodium.57 The average dinner or meal contained 2,233 mg of sodium per 1,000 calories—far in excess of our suggested limit of 1,000 mg per 1,000 calories.

Students at two private schools, Exeter and Andover, served as guinea pigs in another classic experiment.58 The students, who were about 15 years old, were taught to record what they ate in food diaries and to measure their blood pressure. Chefs in both schools were trained to cook lower-sodium meals. The intervention alternated during a two-year period: the chefs at Exeter served the lower-sodium meals one year; the Andover chefs served them the next year. The students in the intervention schools consumed about 15 to 20 percent less sodium—and their systolic blood pressure was an average of 1.7 mm Hg lower than the students eating a regular diet. Girls, who reduced their sodium more than the boys, had greater reductions in blood pressure. The study also demonstrated the power of the food environment. Even though all the students had access to saltshakers, cooking with less salt led to lower sodium intakes. “It is believed that such food preparation practices among young people, if maintained over many years,” the researchers observed, “could have a profound effect on their future risk of . . . hypertension.”

As every parent has heard, it is never too early to get kids off to a healthy start, including keeping them away from most salty packaged foods and restaurant meals. As every parent knows, that is easier said than done, but it starts by having plenty of fresh fruits, vegetables, and other low-sodium foods in the house and then cooking irresistibly delicious low-sodium meals for the whole family. Eating out does not help.

Final Pieces of the Sodium Puzzle

Health experts have long agreed on two critical and uncontested facts based on massive evidence: (1) sodium boosts blood pressure and (2) the higher the blood pressure, the greater the risk of heart attacks and strokes.59 Based on those findings, most hypertension experts have concluded that diets higher in sodium cause cardiovascular disease. But the sodium skeptics have demanded proof that lowering sodium lowers disease risk, not just blood pressure. A small, but important, body of research shows just that.

One piece of evidence comes from observational studies, which follow hundreds or thousands of people over several years. The researchers then correlate how much sodium people consumed at the beginning of the studies with disease rates at the end. This kind of research is informative, but it cannot prove cause and effect.

European Union scientists combined the results of more than a dozen observational studies into one meta-analysis.60 Each of the studies had limitations, but the meta-analysis technique, by greatly increasing the number of people studied, can oftentimes increase the ability to detect associations between different lifestyles and various diseases. In this case, the researchers found a consistent relationship between sodium and cardiovascular disease. Higher sodium intake was associated with a 23 percent higher risk of stroke and, when one low-quality report was excluded, a 17 percent higher risk of total cardiovascular disease. However—and all too often there is a “however” or “but” when discussing nutrition research!—observational studies and meta-analyses of them (as I discuss in chapter 3) have serious weaknesses, especially regarding the accuracy of measuring sodium intake and the possibility that people consuming less sodium may have overall healthier diets and lifestyles, which can undermine their reliability.

The biggest observational “study” involved the entire British population. In 2003, the British government began a serious campaign, which I describe more fully in chapter 7, to encourage consumers to choose lower-sodium foods and encourage industry to lower sodium levels in their products. The goal was to cut sodium consumption by more than one-third, from 3,800 to 2,400 mg per day. By 2008, daily sodium intake fell by 360 mg per person, or about 9 percent.

The British National Institute for Health and Care Excellence estimated that the campaign, “which cost just £15 million [$30 million at the time61], led to approximately 6,000 fewer [cardiovascular disease] deaths per year, saving the UK economy approximately £1.5 billion [$3 billion] per annum.”62 By 2011, the Department of Health reported a 15 percent reduction in sodium, from 3,800 to 3,240 mg per day63 (the government later revised the reduction down to 11 percent64). A 15 percent reduction was estimated to have contributed to an 11 percent reduction in stroke mortality and a 6 percent reduction in fatal heart attacks, preventing 9,000 non-fatal cardiovascular events and 9,000 deaths per year.65 The health department estimated that getting sodium down to 2,400 mg per day would lead to 14,000 to 20,000 fewer deaths annually.66 Note that those were computer-based estimates of health benefits, not direct observations of actual deaths.

Impressive as the British experience and the meta-analysis of observational studies might appear—along with the undisputed fact that higher sodium intakes raise blood pressure—they still did not prove in a single controlled trial that higher sodium levels cause disease, or that lowering intakes to the recommended 2,300 mg per day (let alone to the 1,500 mg that some authorities recommend for many people) would prevent disease. Sodium skeptics, including those who argue that lowering sodium intakes could be harmful, continued to insist that RCTs must be conducted before consumers should sharply reduce their sodium intakes and before governments should force industry to produce lower-sodium foods. But that’s easier said than done. RCTs sensitive enough to detect differences in rates of stroke and heart disease are tough to do and expensive. They necessitate following large groups of people consuming similar diets except for sodium content over a long period of time. No perfect study has been done, but several controlled trials that lowered sodium intake did demonstrate a lower risk of cardiovascular disease.

In one of the best-known experiments, researchers in Taiwan used as their “laboratory” a large retirement facility for veterans, where the men’s diets could be carefully controlled.67 In two of the facility’s five kitchens, they replaced half the regular salt with potassium chloride, which is somewhat salty and lowers blood pressure. But they were not able to replace soy sauce and the flavor enhancer monosodium glutamate (MSG), both big sources of sodium, with potassium-containing versions. The change in salt lowered sodium consumption by about one-third and almost doubled potassium intake. The sodium and potassium intakes of veterans who ate meals from the three other kitchens remained the same. After two and a half years, deaths due to cardiovascular disease dropped a remarkable 41 percent among the veterans who ate the lower-sodium, higher-potassium meals. The study also demonstrated reduced medical costs. Those are remarkable effects that resulted from simply replacing less than half the salt in the men’s diets with potassium chloride.

Notwithstanding its clear-cut results, the Taiwan trial still does not settle the dispute about whether lowering sodium intake to the recommended 2,300 mg decreases disease rates. That is because the “low” level of sodium in the Taiwan study was actually pretty high—about 3,800 mg per day, far more than what elderly American men consume.68 (The control group consumed about 5,200 mg of sodium per day.) So the study could not establish the effects on health of consuming the recommended intake, nor could it determine whether the veterans’ improved health was due to consuming less sodium, or more potassium, or (probably) both. (I have more to say about potassium later in this chapter and in chapter 9.)

Other key research on sodium and cardiovascular disease was done in the United States. Appel and his colleagues conducted two Trials of Hypertension Prevention (TOHP I and the much larger and longer TOHP II).69 The 3,000 participants were 30 to 54 years old and had prehypertension. The researchers trained about half the participants in the first trial to lower their sodium intake for 18 months and in the second trial for three to four years. The other half served as a control group in each trial. The intervention groups lowered their average sodium intake by about 1,200 mg per day, or one-third. As expected, the lower intakes were associated with slightly lower blood pressure. The declines were small (systolic blood pressure was reduced by less than 2 mm Hg) though not a surprise, considering that the participants were only 30 to 54 years old and did not have hypertension. Still, in TOHP II the incidence of hypertension was 18 percent lower in the sodium-reduction group; no change was seen in the briefer, smaller TOHP I. (Another part of the studies found that weight loss led to somewhat greater reductions in blood pressure than consuming less salt.)

The TOHP researchers continued to track the participants for 15 years after the controlled part of TOHP I ended and 10 years after the controlled part of TOHP II ended. Their major finding was impressive. The participants who had cut their sodium intake enjoyed a 25 to 30 percent lower risk of cardiovascular events compared to the control group: the researchers emphasized that TOHP “provides some of the strongest objective evidence to date that lowering sodium intake, even among those without hypertension, reduces the risk of future cardiovascular disease.”70 The follow-up was an uncontrolled extension of the controlled parts of the studies. If anything, participants in the lower-sodium group probably gradually increased their sodium intake, which would have lessened the reduction in cardiovascular events.

The authors recognized that the substantial reduction in cardiovascular disease might seem unrealistically large considering that blood pressure was just a bit lower in the people who reduced their sodium intake. But they speculated that in addition to boosting blood pressure, consuming more sodium might be causing harm in other ways, such as stiffening tiny arteries or thickening the heart muscle. They said that such “mechanisms may explain the sizeable reduction in cardiovascular disease, despite the relatively modest effects on blood pressure seen during the TOHP trials.”71

Fiona Godlee, the editor of the BMJ (formerly the British Medical Journal), where the paper was published, applauded the TOHP follow-up study, saying it “may be the final bugle call in the battle of the evidence.”72 But alas, bugles kept calling, as we’ll see in chapter 3.

To add some statistical muscle to the TOHP and TONE trials, a committee of the NAM combined them into a meta-analysis. It found that people eating the lower-sodium diets had a 26 percent reduction in the incidence of any form of cardiovascular disease (including angina, strokes, heart attacks, and others).73 A somewhat broader meta-analysis published in 2020 found a statistically significant 20 percent decrease in disease for every 1,000-mg decrease in sodium.74

A British group that conducted a similar meta-analysis found a similar result with borderline statistical significance. It emphasized the need for more effective ways than just cajoling people—the approach that has failed for several decades—to lower sodium consumption.

In any case, while the meta-analyses included just a handful of studies with modest numbers of participants, the positive findings were certainly supportive of the conclusion that lowering sodium intakes reduces the risk of heart disease and strokes, but were not decisive enough to end the controversy.

Health and Economic Benefits from Lowering Blood Pressure

Many studies have quantified the decreases in blood pressure when sodium consumption is lowered. Many others have quantified the reduction in cardiovascular disease when blood pressure is lowered. Based on those two bodies of information, health economists have used computer-based methods to estimate the population-wide benefits—in terms of illnesses, deaths, and dollars—of lower sodium consumption. Their findings are eye opening:

- • The first estimate I am aware of was made in 2004: Stephen Havas (from University of Maryland School of Medicine), with Edward Roccella and Claude Lenfant (both from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI], which researches cardiovascular disease) estimated that cutting sodium by 50 percent in packaged and restaurant foods would save 150,000 lives per year.75

- • Kartika Palar and Roland Sturm at the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, California, using more sophisticated methods, estimated that reducing sodium intake from 3,400 mg per day to 2,300 mg would reduce the prevalence of hypertension by 11 million people and save $18 billion in healthcare costs each year.76

- • Researchers at Harvard and elsewhere estimated that sodium consumption in excess of 500 mg per day, which they considered the theoretical minimum intake (but impossible for Americans to attain), was causing about 100,000 premature deaths annually.77 Reducing sodium less would have proportionately smaller benefits.

- • In 2010 a team led by Stanford University researchers estimated the effects of a small, 9.5 percent reduction (only about 350 mg per day) in sodium.78 Reducing sodium by that amount would translate into a seemingly tiny 1.25 mm Hg decrease in the systolic blood pressure of people aged 40 to 85. But the researchers estimated that the small decrease would avert about a million strokes and heart attacks, as well as save more than 1.3 million years of life and an estimated $32 billion in direct medical costs, over the people’s lifetimes.

- • Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo of the University of California, San Francisco, and her co-authors calculated that reducing sodium intake by 1,200 mg per day (about one-third) would prevent 44,000 to 92,000 deaths per year.79 They also estimated that a reduction of 1,200 mg per day would save $10 billion to $24 billion in healthcare costs annually—similar to Palar and Sturm’s estimate. The researchers said that such an intervention would be more cost-effective than using medications to lower blood pressure in everyone with hypertension.

- • Subsequently, Bibbins-Domingo and fellow researchers estimated that current sodium intakes were causing 110,000 more deaths per year than if average intake was 1,500 mg per day.80 They also estimated that gradually decreasing intakes by 4 percent (145 mg) a year for 10 years, or from 3,600 mg to about 2,160 mg per day, would save an average of 28,000 to 50,000 deaths per year over 10 years (many more in the tenth year than the first year). In the understated lingo of medical journals, the authors concluded that the “magnitude of health benefit for the US population will be substantial.”

- • Researchers led by Dariush Mozaffarian, the dean of the Gerald J. and Dorothy R. Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University, estimated that lowering sodium to 2,000 mg per day would save more than 50,000 lives per year.81

- • European and American scientists estimated that gradually lowering sodium in food over 10 years until diets included only 2,300 mg of sodium per day would save 83,000 lives and $57 billion in health-related costs over 20 years (and even more over lifetimes).82 Differences in methodology led to lower estimates than in the other studies, but the scientists found that even much smaller reductions in sodium still would be highly cost-effective.

- • Analysts at the US Department of Health and Human Services (FDA’s parent agency) calculated that a one-third reduction in sodium consumption (1,264 mg per day) would save $10 billion a year in medical expenses and $142 billion over 20 years.83 Unlike the other studies, they estimated the value of having longer, healthier lives: $239 billion in one year and $3.556 trillion over 20 years. “A total value of about $3,699 billion over 20 years.” (Because sodium would not be reduced instantaneously, the actual benefits would be less. Also, based on previous research they valued a healthy year of life at $400,000, higher than what other government agencies have assumed. On the other hand, they only considered benefits flowing from lower blood pressures and not other possible benefits of reduced sodium intakes.)

Because the health economists used different statistical methods, different reductions in sodium, and different estimates of the effects of lowering sodium on blood pressure, their estimates of benefits are not directly comparable. Some of the projected cost-savings may be exaggerated, because the people who lived longer would have additional medical expenses and greater Social Security costs. Also, some critics question whether lower sodium intakes always translate proportionately into lower blood pressure and whether lower blood pressure always means lower death rates.84 On the other hand, the benefits might be underestimated, because they did not include any of sodium’s possible detrimental effects other than the contribution of blood pressure to heart attacks and strokes (as I discuss later in this chapter). Finally, when researchers refer to deaths prevented, they really mean deaths postponed.

The CDC director Tom Frieden and his colleague Peter Briss were certainly emphatic when they told physicians in 2010 that about 100,000 deaths a year could be attributed to excess sodium. After all, that is more deaths than are caused by alcohol consumption85 and two-and-a-half times as many as are caused by motor vehicle crashes.86 “After tobacco control,” Frieden and Briss wrote, “the most cost-effective intervention to control chronic diseases might be reduction of sodium intake.”87

The bottom line is that America is suffering an astounding tens of thousands of unnecessary deaths and wasting many billions of dollars annually simply because we are consuming too much sodium. That kind of toll would cause a national furor if the deaths were immediately obvious after eating a salty meal. But the harm from overly salted foods accumulates quietly and invisibly over the decades. No one writing obituaries or filling out death certificates attributes premature deaths to “salty diet.” So, instead of being outraged and taking action, people continue to dine obliviously on high-sodium foods, most food manufacturers and restaurants do little to slash sodium levels in their products, and the federal government, largely because of industry pressure, has not made lowering sodium a high priority.

Giving Drugs Their Due

While it is far better to avoid high blood pressure in the first place than to get it and then try to treat it, we need to give drugs their due. After all, most people with high blood pressure would much rather just take a few daily pills than undertake the chore of improving their diets, losing weight, and exercising more. And taking drugs is certainly the fastest, most convenient, most effective way to reduce blood pressure quickly. Antihypertensive medications, such as diuretics and ACE inhibitors, deserve much of the credit for the plummeting incidence of stroke since the 1960s.88 (The reduced need for salt-preserved foods, thanks to greater use of refrigerators and freezers, might also have played a significant role in the decline in stroke rates since 1925.)89

As extraordinary as drugs are, though, they have their limitations. A Canadian study found that half of newly diagnosed patients stopped taking their hypertension medications within three years.90 European investigators found that about half of the patients stopped taking the drugs within one year.91 People stop taking the drugs because of cost, or because hypertension has no symptoms and is easy to ignore, or because taking drugs every day is an easily forgotten nuisance. Drugs may cause side effects, such as disturbed sleep, headache, muscle cramps, a cough, and an increased need to urinate. Another concern emerged in 2018 and 2019 when companies had to recall from the marketplace some widely used hypertension drugs containing valsartan, irbesartan, and losartan, because they were contaminated with cancer-causing chemicals.92

But let’s look again at cost. With hypertension being the single most commonly treated health condition, antihypertensive drugs cost Americans upwards of $20 billion per year.93 That is about six times the entire annual budget of the NHLBI.94 Beyond drugs, Americans spend an additional $27 billion for doctor visits, emergency room costs, and other care related to hypertension. That is about eight times the annual budget of NHLBI.

About 1 out of 10 people with hypertension experience “resistant hypertension” that cannot be sufficiently reduced even by taking as many as three antihypertensive medications.95 A healthier diet can be lifesaving for them. In one tightly controlled study of a dozen such patients, switching from a high-sodium (5,750 mg/day) to a low-sodium (1,150 mg/day) diet dramatically reduced blood pressure within one week from 152/85 mm Hg to a much safer 131/75 mm Hg.96 Those results suggest that many people with resistant hypertension are “exquisitely salt sensitive.” The American Heart Association called that study “compelling.”97

While consuming less salt is important, it is not the only way to reduce blood pressure and its deadly consequences. Maintaining a healthy weight is a top priority. And, as DASH demonstrated, so is consuming plenty of foods rich in potassium—such as bananas, sweet potatoes, salmon, lentils, peas, cooked spinach, and many more, as shown in chapter 11 (table 11.2)—to counteract the blood pressure–raising effect of sodium. It is equally important to refrain from smoking cigarettes and to limit alcohol consumption to no more than two drinks per day. Last but not least, remember that getting plenty of physical activity is associated with healthier blood pressure and many other benefits. But in theory—and without requiring each individual to make lifestyle choices many times a day—perhaps the easiest, most efficient way to improve blood pressure would be for companies to lower sodium levels substantially throughout the food supply.

More Damage Due to Hypertension

High blood pressure takes its toll on the kidneys and the eyes; it challenges some of our normal bodily functions and exacerbates the role that aging plays in others. In the sections below I offer several more reasons to switch to a low-sodium diet.

Cut the Salt . . . for Your Kidneys

High blood pressure is a major risk factor for chronic kidney disease (CKD). The CDC estimates that some 30 million adults have CKD, and most are undiagnosed. Kidney disease is the ninth leading cause of death and enormously expensive. Medicare paid $114 billion in 2016 to treat chronic and end-stage kidney disease (in which patients need dialysis or a kidney transplant),98 with private insurance and patients paying tens of billions more. Across the globe, kidney disease kills as many as 5 to 10 million people every year.99 Because most people who have chronic kidney disease do not even know it, the National Kidney Foundation calls kidney disease “the under-recognized public health crisis.”100

Kidneys are key workhorses in the human body. To keep the body functioning optimally, kidneys maintain healthy levels of calcium, sodium, potassium, and other minerals that circulate in the blood. To filter extra water and wastes (including sodium) out of the blood, they make urine. The kidneys also release hormones that help make red blood cells, regulate blood pressure, and keep bones strong.

But elevated blood pressure makes it harder for kidneys to excrete water. That leads to fluid build-up and even higher blood pressure—and the cycle continues, possibly leading to kidney failure (also called end-stage renal disease), the often-deadly end result of CKD. Diets high in sodium, potassium, phosphorus, and water can be especially harmful to the kidneys of elderly, obese, diabetic, or black patients with kidney failure.101

Numerous experiments have tested diets high or low in sodium in patients with various stages of chronic kidney disease. A meta-analysis of good studies (all used 24-hour urine collections to measure sodium excretion) found that a low-sodium diet not only reduced blood pressure, but also the amount of protein in urine, a hallmark of kidney disease.102 The researchers, based at the University of Campania in Naples, Italy, said that the big challenge is overcoming the food environment and making it easier for patients to eat a lower-sodium diet over the long term.

The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC), a major, seven-year-long study involving more than 3,700 people with kidney disease, explored the effect of sodium, not just on blood pressure and markers for kidney disease, but on rates of heart disease. It found that patients consuming a high-sodium diet—more than about 4,500 mg of sodium per day—had a 50 percent greater risk of cardiovascular disease than those who consumed under 2,900 mg.103 The high sodium levels (based on multiple 24-hour urine collections) seemed to be harmful in ways in addition to boosting blood pressure, possibly by interfering with blood vessels’ ability to expand and contract. CRIC should inspire people suffering from kidney disease to stick to a lower-sodium diet.

. . . for Your Eyesight

High blood pressure can affect the eye in several ways. A stroke (or even a TIA) can damage the part of the brain that processes visual images. It can also damage the optic nerve, which carries information from the retina—the light-sensitive part of the eye—to the brain.104 Those effects cause partial loss of vision, blurred vision, or droopy eyelids. Such symptoms should trigger an immediate trip to the emergency room.

High blood pressure also can thicken or stiffen tiny blood vessels in the retina, a condition called retinopathy. The retina is the light-sensitive part of the eye that receives light and sends the information to the brain. An “eye stroke” occurs when the flow of oxygen-rich blood to the retina is blocked.105 That could lead to permanent blurred vision or even blindness. Diet and drugs need to be used to prevent or reverse the damage.

. . . to Fight Cognitive Decline and Dementia

A landmark trial funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) found that reducing systolic blood pressure by means of pharmaceuticals from 140 mm Hg down to normal levels—120 mm Hg—led to an almost 20 percent decrease in mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI is characterized by a decline in memory and thinking skills.106 The risk of dementia itself also appeared to decline by almost as much, but the decrease was not quite statistically significant. Those results, from the SPRINT MIND study, are certainly promising but need to be replicated before they will be widely accepted. Presumably, reducing blood pressure by means of a low-sodium diet, as well as losing weight and other lifestyle changes, would also improve cognition.

Kristine Yaffe, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote about SPRINT MIND in the Journal of the American Medical Association, saying that it “offers great hope.”107 Maria C. Carrillo, the chief science officer of the Alzheimer’s Association, was a bit more exuberant, exclaiming, “to reduce new cases of MCI and dementia globally we must do everything we can—as professionals and individuals—to reduce blood pressure to the levels indicated in this study, which we know is beneficial to cardiovascular risk.”108

Research on mice supports the link between salt and mental performance. Scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City and Washington University in St. Louis found that consuming a diet several times saltier than what Americans consume for just eight weeks impaired the mice’s normal nest-building activities—they spent less time and used less nesting material than normal mice—and their memory.109 Costantino Iadecola, one of those researchers and the director of the Feil Family Brain and Mind Research Institute (BMRI) at Weill Cornell, said, “mice fed a high-salt diet developed dementia even when blood pressure did not rise.”110 Digging deeper, the scientists found that the high-salt diet reduced the production of nitric oxide, which in turn altered proteins in the brain in the same way that the proteins are altered in patients suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. Interestingly, the salty diet acted on cells in the gut to produce the molecules (interleukin-17) that reduced nitric oxide production in the brain.

. . . to Prevent Headaches

Two high-quality RCTs—DASH–sodium (involving people with normal or high blood pressure) and TONE (involving people with hypertension)—found that people who reduced their sodium intake had fewer headaches.111 The researchers speculated that the headaches might be caused either by increased blood pressure or by a direct effect of sodium.

. . . to Relieve Erectile Dysfunction

The link between high blood pressure and erectile dysfunction (ED) is so well known that doctors use the occurrence of ED as an indication that a man might have previously undetected high blood pressure or heart disease.112 High blood pressure causes ED because it stiffens and narrows arteries, reducing blood flow to the penis and making it difficult for men to have an erection. The problem becomes increasingly prevalent as men age, with the rate of complete impotence tripling from 5 percent in 40-year-olds to 15 percent in 70-year-olds.113 Exacerbating the risk of ED for men with high blood pressure are the medications used to treat hypertension: some of them, including diuretics and beta blockers, may themselves cause ED and contribute to the popularity of Viagra and similar drugs among seniors.

According to the Mayo Clinic, high blood pressure may also affect a woman’s sex life. It does so by reducing blood flow to the vagina, possibly leading to a decrease in sexual desire, vaginal dryness, or difficulty achieving orgasm.114

Potassium: Salt’s “Friendly Co-conspirator”

Potassium is an essential nutrient that helps maintain fluid and electrolyte balances and normal cell function. According to Emory University researchers, our Stone Age ancestors, with their largely plant-based diets, consumed 10,000 mg or more of potassium per day (and under 1,000 mg of sodium), a level that is unheard of in the United States.115 That was the high-potassium dietary environment in which early humans and their primate predecessors evolved. In fact, the Emory researchers observed, “Americans, like nearly all people living today, consume more sodium than potassium. Humans are the only free-living, non-marine mammals to do so.” Our bodies are not designed to function optimally when we are consuming so little potassium and so much sodium.

Higher potassium intakes reduce blood pressure.116 For example, researchers at the World Health Organization (WHO) and elsewhere conducted meta-analyses of clinical trials that looked at potassium’s effect on both blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. The meta-analyses found that people with hypertension who consumed 3,500 to 4,700 mg of potassium per day ended up with a 7 mm Hg lower systolic and a 4 mm Hg lower diastolic blood pressure than those in control groups who consumed less.117 The scientists also combined observational studies into another meta-analysis that found about a 25 percent reduced risk of stroke in people who were consuming at least the recommended amount of potassium. But they did not see a decrease in heart attacks. And neither did they (nor did others) detect much, if any, benefit for people without hypertension.118

Another meta-analysis of observational studies, this one performed by Italian scientists, found similar results. Consuming more potassium (1,500 mg more per day) was associated with a 20 percent reduced risk of stroke in the general population.119 In addition, they saw smaller reductions in coronary heart disease and total cardiovascular disease, but those were not statistically significant. The researchers estimated that increasing potassium intake by 1,500 mg per day throughout the world could prevent a million stroke deaths per year.

Because consuming less sodium and more potassium both reduce blood pressure, the ratio of sodium to potassium in the diet appears to be a better indicator of the risk of hypertension than the amounts of sodium and potassium looked at individually.120 According to the American College of Cardiology and other health groups, “A lower sodium–potassium ratio [is] associated with a lower level of [blood pressure] than that noted for corresponding levels of sodium or potassium on their own.” A high potassium intake could help lower the risks related to a high sodium intake.121 Likewise, a low sodium intake could reduce the need for potassium. But the bulk of research suggests that lowering sodium has more impact than raising potassium.122 My advice is to both reduce sodium and increase potassium to maximize your health benefit.

The NAM recommends that women should consume at least 2,600 mg of potassium per day and men 3,400 mg per day, with no concerns about consuming more.123 The WHO recommends an intake of at least 3,500 mg per day.124 The American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, and other health groups consider higher potassium intakes to be one of the best non-pharmaceutical means of lowering blood pressure.125 They recommend that people with hypertension, whether they are taking medications or not, should consume 3,500 to 5,000 mg per day. While the average person may consume an adequate amount of potassium,126 it could only be helpful—particularly for people with high blood pressure—to consume more, especially from healthy diets. Potassium supplements are not a great option because they rarely contain more than 99 mg of potassium per pill, which is only about 3 percent of a day’s recommended intake. (The FDA requires a warning label on pills with more potassium out of fear that the higher dose might cause ulcerative lesions in the small intestine.)127 To get more potassium, consumers should eat more potassium-rich foods (see chapter 11, table 11.2); they could also use a potassium-containing salt substitute when they cook or at the table (see chapter 9).

Beyond Blood Pressure: Other Potential High-Salt Risks

Higher blood pressure and the ensuing higher risk of cardiovascular disease are the most serious and common harmful effects of salty diets. But salty diets also may undermine health in other ways. Measured in terms of lives and dollars, the harm caused by high-sodium diets may be much greater than the estimates discussed earlier, because those estimates were based only on salt’s effect on blood pressure and blood pressure’s effect on cardiovascular disease. Let’s explore briefly some of the other ways that high-sodium diets appear to affect health.

Stones and bones

“Kidney stone pain is not subtle,” says Dr. Gary Curhan, a professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.128 It is often described as being worse than childbirth. High intakes of sodium stimulate the body to excrete calcium, while potassium has the opposite effect.129 The extra calcium in the kidney can crystallize into stones, which range in size from a grain of sand to a ping-pong ball. The evidence on sodium and calcium excretion led He and MacGregor to conclude that salt intake is an important cause of kidney stones.130 Almost everyone who has had a kidney stone would urge people to do everything imaginable—including lowering sodium intakes, drinking plenty of fluids, and eating a DASH diet—to avoid them.

Whether salty diets not only increase calcium excretion but also lead to osteoporosis is still an open question.131 One trial found that high sodium intakes were not detrimental to older women’s bones.132 But those women were given calcium supplements to boost their average intake to about 1,400 mg per day, roughly 50 percent higher than women in the general public. Similar trials need to be conducted with women who have marginal calcium intakes, as is the case for all too many people.

In the absence of conclusive evidence regarding bone health, Bess Dawson-Hughes, director of the Bone Metabolism Laboratory at Tufts University’s Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, offers some sensible bottom-line advice:

Higher salt intake triggers greater calcium excretion. People with a low calcium intake would be most vulnerable to the adverse effect of sodium intake on bone. While offsetting the adverse effect of excess sodium intake by increasing calcium intake would be one strategy, the general recommendation to reduce salt intake for bone health is sound, especially since salt intake is far above recommended levels in most diets.133

Obesity

The global epidemic of overweight and obesity has many causes. Surprisingly, salt, which has no calories, may be one of them. When Feng J. He and her colleagues analyzed the diets of British children, they found that increased sodium intake correlated with both overall fluid intake and soft drink intake.134 The scientists then calculated that by cutting salt intake in half, the children would consume an average of 2.3 fewer eight-ounce servings of sugar drinks—a definite cause of obesity—per week. They further calculated that drinking that many fewer sugar drinks could reduce the number of overweight and obese children by more than 15 percent. Richard Horton, the plainspoken editor of the Lancet, offers an explanation: “Salt makes you thirsty. Without salt, our need to guzzle endless soft drinks would evaporate.”135

But there might be salt-related mechanisms other than through increased consumption of sugar drinks that promote obesity. In a study that collected 24-hour urine samples to measure sodium intake, scientists at the CDC, the National Center for Health Statistics, and NIH found a strong association between sodium consumption and overweight and obesity.136 That association remained even after they accounted for different soft drink and calorie intakes, suggesting that sodium might act directly on hormone levels or other factors. The authors concluded, “Our findings, together with others, provide important evidence suggesting that high sodium intake may play a role in obesity.”

Another recent study done by an international group of researchers looked at possible links between sodium intake and obesity in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States.137 It found significant associations in all four countries (after controlling for calorie intake, physical activity, and other factors). In the United States, every 400 mg increase in sodium consumption was associated with a 24 percent increased incidence of overweight and obesity.

That (or other) research does not prove that salty diets are a cause of obesity. But there certainly is some smoke, and further research may find a fire.

Bloating, edema

Salty foods may lead to bloating or edema. That issue is discussed more on women-oriented websites than in medical journals, but millions of women and men alike would swear to it. Edema might show up as swollen fingers, feet, or ankles. When people increase their sodium intake, their bodies retain more water to dilute out the sodium, and that may lead to feeling bloated.138 The ever-informative DASH–sodium trial provided scientific evidence that a higher-sodium diet increases bloating.139

Stomach cancer

The World Cancer Research Fund found “strong evidence” that consuming foods preserved by salt increases the risk of stomach cancer.140 The main culprits appeared to be foods like pickled vegetables and salted or dried fish as traditionally prepared in East Asia. Those foods may irritate the delicate lining of the stomach, inviting infections from Helicobacter pylori bacteria, the underlying cause of many cases of stomach cancer (and stomach ulcers). But few Americans eat that kind of diet. In addition, when researchers looked at total salt intake, not just salt-preserved fish and pickled vegetables, they did not find an association with stomach cancer.141 Cancer should be near the bottom of your list of salt-related worries.

Summarizing the Science

Copious evidence from numerous kinds of studies proves that consuming less sodium reduces blood pressure and that lower blood pressure reduces the risks of heart attacks and strokes, as well as kidney disease. In addition, some of the research indicates that lowering sodium reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease via mechanisms other than lowering blood pressure. Meanwhile, computer models based on the relationships between sodium, blood pressure, and disease have estimated that reducing sodium intakes to healthy levels would prevent tens of thousands of deaths and save many billions of healthcare dollars each year. Consuming more potassium would increase those benefits.

Notwithstanding that research, some well-credentialed critics at major universities contend that “there is not a shred of evidence whatsoever” to prove that a lower-sodium diet is healthier than the current American diet, but rather argue that lowering sodium would actually be harmful.142 In this chapter I have sought to explain that there is much more than “a shred of evidence” that lower-sodium diets would save many lives. In the next chapter let’s examine the evidence that consuming less sodium would be harmful.