7

Less-Salty Diets around the Globe

Globally, 1.65 million deaths from cardiovascular causes . . . were attributed to sodium intake above 2,000 mg per day. . . . These deaths accounted for nearly 1 of every 10 deaths from cardiovascular causes.

—Global Burden of Diseases Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group,

New England Journal of Medicine1

Hypertension is a global problem. The condition causes more deaths than any other single factor. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the number of people with uncontrolled hypertension jumped from 594 million in 1975 to 1.13 billion in 2015. Two-thirds of them lived in low- and middle-income countries, and less than one out of five had their hypertension under control.2 The WHO and others have also estimated that raised blood pressure causes about 10 million deaths per year, or about 17 percent of all deaths.3 Although many factors such as obesity and aging populations contribute to that toll, salty home-cooked meals or processed and prepared foods are certainly a major factor.

The massive Global Burden of Disease study, which involves more than 3,600 researchers around the world and is based at the University of Washington in Seattle, has looked at the relationship between diet and cardiovascular disease in 195 countries.4 It concluded that high sodium intake was the greatest cause of diet-related deaths—about 1 million to 5 million per year—with diets low in dietary fiber and fruit not far behind. Those three dietary problems were responsible for half of all diet-related deaths. Another report pegged the number at 1.1 million to 2.2 million deaths per year, including almost 90,000 in the United States.5 In response to such evidence, a number of governments are working aggressively to lower sodium intakes, and some multinational and local companies have started to market less-salty foods.

A young nonprofit organization called Resolve to Save Lives is spurring progress in low- and middle-income countries, starting with China, Ethiopia, Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines. It is funded by major foundations and headed by Tom Frieden, the former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One of its three goals is to prevent millions of deaths by lowering sodium levels in the food supply.6

More and more governments around the world are recognizing the health problem and the cost problem. Governments and individuals spend billions of dollars a year treating hypertension and its consequences. Lowering sodium levels in the overall food supply could save a good chunk of those expenses. And a growing number of major manufacturers both acknowledge the public health benefits of lowering sodium and anticipate that if they do not voluntarily reduce sodium now, they will be forced to do so in the future.

Fortunately, the controversy over whether consuming less sodium would be good or bad that has slowed progress in the United States has not infected the rest of the world. Elsewhere, it is generally accepted that people should gradually, but greatly, reduce their sodium intake.

Finland was a salt-reduction pioneer, for instance, because of the extremely high sodium consumption of its residents (one-fourth greater than the amount Americans consume). Beginning in 1979, Finland’s government sponsored a huge public education campaign, which was supported with legislation and other measures.7 It pressured companies to market healthier products by lowering both sodium and saturated fat. Finland also allowed a heart-healthy symbol to be used on packaged foods with less than specified levels of sodium and required a warning notice on foods with excessive levels. It achieved a major reduction in sodium of at least 1,600 mg per person per day, or about one-third.8 Rates of heart attacks and strokes declined by about two-thirds, despite increases in obesity and alcohol consumption. Unfortunately, since 2002 the Finnish effort has flagged, as have further reductions in sodium consumption.

Campaigns in northern Japan, where diets were among the world’s saltiest, yielded decreases almost as big.9 Lower sodium intake coupled with medications, community-based education, and other actions combined to lower the stroke rate by more than 85 percent.10

Currently, dozens of countries, ranging from Turkey to Argentina to Thailand, are working to reduce sodium in the food supply.11 Countries have used education, regulations, and taxes to cut sodium. Hungary, for instance, slapped a small tax on salty snacks and condiments. Fiji imposed a 32 percent tariff on monosodium glutamate. Turkey, where sodium intakes averaged 7,200 mg per day, used education and voluntary limits to reduce consumption by 16 percent over four years.12 Table 7.1 lists some of the growing number of international efforts to limit sodium.13

Battles over sodium have been waged in the United Kingdom for more than a quarter century. In 1994, after much debate, a government advisory committee on food policy recommended a one-third reduction in salt intake, from 3,600 mg per day to 2,400 mg per day. How did the food industry behave? Fiona Godlee, editor of the BMJ, described it in unusually sharp language for an august medical journal:

The food industry has lobbied fiercely against the threat to its profits. . . . Rather than reformulate their products, manufacturers have lobbied governments, refused to cooperate with expert working parties, encouraged misinformation campaigns, and tried to discredit the evidence.14

Worse, Britain’s chief medical officer cast doubt on the evidence linking high sodium intakes to high blood pressure and stressed that the committee’s recommendation was not going to be accepted as government policy.

But the battle over salt was just starting. The United Kingdom has been fortunate to have a persistent, knowledgeable, passionate—and effective—physician wage a multifaceted campaign to lower sodium consumption. Literally for decades, Graham A. MacGregor, a physician trained as a kidney specialist, together with his steadfast colleague Feng J. He, a physician and epidemiologist, have chastised industry for harming consumers and chastised the government for allowing industry to do so. MacGregor might well be called the Rachel Carson of salt reduction. As a professor of cardiovascular medicine at the Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine at Queen Mary University of London, he conducts original research and is a prolific author of scientific papers. In addition to that, he is a strategist, lobbyist, and publicist dedicated to preventing cardiovascular disease in the United Kingdom and around the world. In 2019 he was honored for his long and impactful career by being appointed a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire—not quite knighthood, but close.15

Table 7.1

International actions to limit sodium

|

Argentina |

A 2013 law set modest sodium reductions for 18 categories of meats, bread products, cheeses, and soups to be achieved by 2015. For example, the law limits average sodium in hamburger meat to 850 mg and in instant soups to 352 mg per 100 grams (3.5 oz.). If achieved, such cuts would cut sodium consumption by about 350 mg per day and prevent an estimated 19,000 deaths over 10 years. Some provinces banned saltshakers from tables at restaurants, but that has not been well enforced. |

|

Australia |

Twenty sodium-reduction targets were set for nine food categories: breads, breakfast cereals, simmer sauces, soups, processed meats, savory pies, potato chips, extruded snacks, savory crackers, and cheese. Participating companies (more than 35) determine individually which products to reformulate and the extent of reduction. By 2013 the average sodium level in breads was reduced by 9%, breakfast cereals by 25%, and cured meats by 8%. |

|

Austria |

Many bakeries committed to reduce the salt content of bread products by 15% by 2015. |

|

Bahrain |

Reducing sodium in bread, most of which is produced by a government-owned bakery. |

|

Belgium |

A 1985 rule limited the sodium content in bread to 480 mg per 100 grams. In 2009 the government set voluntary goals for 13 food categories. |

|

Brazil |

In 2011, the food industry agreed to reduce sodium across 16 food categories by 2.5% to 19.5%. Full implementation is set for 2020. |

|

Bulgaria |

In 2012, mandatory limits were set for bread (480 mg of sodium per 100 grams), cheese, meat and poultry products, and lutenica (a vegetable relish product). |

|

Canada |

A Sodium Reduction Strategy was finalized in 2012, with modest results through 2018. A plan for front-of-package warning notices was proposed but not finalized. |

|

Chile |

Requires “High in Salt” warning labels on foods with more than 400 mg per 100g (or 113 mg per oz.) for solid foods and 100 mg per 100 ml (or 240 mg per 8 fl. oz.) for soups, beverages, and other liquid foods. |

|

Ecuador |

Requires prominent label notices to indicate that foods are high, medium, or low in sodium (and sugar and fat). |

|

Finland |

Since 1992, a “high in salt” notice (not very prominent) has been required on foods with more than a specified amount of sodium. |

|

Greece |

Greece limited the salt content in bread (1.7% salt by dry weight) and tomato products like juice, concentrate, and paste. |

|

Hungary |

A tax is levied on a small number of salty foods and condiments with sodium contents above specified levels. In the first four years, that tax (plus taxes on soft drinks, energy drinks, candies, and other foods) raised $219 million for public health spending. |

|

Israel |

Requires warning notices on solid foods with more than 500 mg of sodium per 100g (and 400 mg for liquid foods); those limits will drop by 100 mg in 2021. Warnings are also required on foods high in saturated fat and sugar; a voluntary healthy symbol is allowed on qualifying foods. |

|

Kuwait |

Goal was to reduce salt in bread by 10% (actual reduction was at least 20%), with other reductions in cheese, corn flakes, pastries, potato chips, French fries, sandwiches. |

|

Mexico |

Requires Chilean-like warning labels on foods high in sodium and other nutrients. |

|

Netherlands |

The maximum salt content for bread is 1.8%, with voluntary limits for other categories. Significant sodium declines were seen in some food categories. |

|

Paraguay |

A 2013 resolution mandated a 25% sodium reduction in bread, the main source of salt for Paraguayans. |

|

Peru |

Requires Chilean-like warning labels on foods high in sodium and other nutrients. |

|

South Africa |

In 2013 limits were set on sodium in bread, breakfast cereals, butter and spreads, savory snacks, potato chips, cured and uncured processed meats, dry soups, and gravies. Implementation deadlines were set for June 30, 2016, and June 30, 2019. Sodium was to be reduced from 2010 levels in bread by 28%, cereals by 37%, and cured meats by 46%. When the 2016 targets were implemented, two-thirds of products already met their targets and many more products had salt levels close to the target. Effort not evaluated. |

|

Turkey |

Limits on sodium in bread (which provides one-third of Turks’ sodium) and some processed foods like tomato paste; banned sale of chips in school canteens in 2011. Sodium intake dropped 20% from 7,200 mg/day in 2008 to 5,800 mg in 2012. |

|

United Kingdom |

Voluntary salt-reduction targets were finalized in 2006 and updated several times. The 85 targets applied to processed meats, bread, cheese, convenience foods, snacks, and other foods. Sodium consumption declined by more than 10%. |

|

United States |

In 2016 the FDA proposed voluntary sodium targets (with 2- and 10-year time frames) for more than 150 food categories, but they were not yet finalized as of spring 2020. New York City and Philadelphia require warning icons on menus for high-sodium (2,300 mg or more) meals at chain restaurants. |

|

Uruguay |

Requires Chilean-like warning labels on foods high in sodium and other nutrients. In 2015 it banned saltshakers, mayonnaise, and ketchup at restaurants in Montevideo and saltshakers from schools nationwide. Montevideo restaurants must offer at least 10% of menu items without added salt. |

MacGregor was incensed that the UK government buckled under pressure from the food industry, which had threatened to withdraw funding it gave to the ruling Conservative Party. So in 1996 MacGregor created a nonprofit advocacy group supported by leading sodium experts called Consensus Action on Salt and Health (later changed to Action on Salt).16 The group successfully pressured the British government to develop a multifaceted sodium-reduction campaign. According to MacGregor, “This required some fairly strong-arm tactics to persuade government officials to take action which they eventually did.”17 He and his colleagues supported the government campaign with efforts to “name and shame” companies that did not lower their sodium levels.18 Later, because salty diets were a problem globally, MacGregor broadened his scope by creating World Action on Salt and Health and enlisted professors from around the world.

Largely because of pressure from the activist professors, several members of Parliament and the Labour government took aim at salt. In 2003 the United Kingdom became the first major country to mount a systematic, but still voluntary, campaign to reduce sodium. In 2006 the government’s Food Standards Agency, which was relatively new and determined to make a difference, specified sodium levels for about 80 categories of processed and restaurant foods that it asked industry to achieve in the next four years.19 The government expected companies to have the average sales-weighted sodium content at or below those levels. And companies were asked to limit the sodium content of any new products to those levels. The UK followed up with three sets of tighter targets in 2009, 2011, and 2014, and proposed a fifth set in 2020 with a 2023 deadline.20 Their latest goal is to reduce Britons’ average sodium intake to 2,800 mg per day.

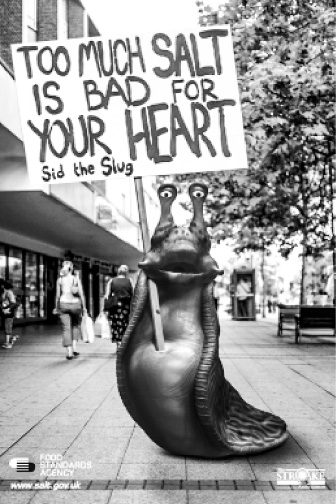

Then instead of leaving those recommendations moldering on bookshelves, where most voluntary recommendations end up, the government mounted a creative advertising campaign, featuring the memorable “Sid the Slug,” to urge consumers to choose lower-sodium foods (see figure 7.1). Salt, of course, is famously used to kill slugs. To play on that, one TV commercial showed Sid in a parking garage, where he freaked out at a woman loading grocery bags into her car. His father—“dead now,” the slug said—had once offered him some good advice: “Stay away from fast cars, loose women, and SALT.”21

But more important than the ad campaign, the UK government publicly and privately pressured companies to lower sodium levels. As I discussed in chapter 2, after five years lower-sodium diets were preventing 6,000 premature deaths per year. Several years later, further declines were calculated to be preventing as many as 9,000 deaths per year.22

Figure 7.1

Sid the Slug was a key spokescharacter in the UK’s salt-awareness campaign.

Unfortunately, after a 2010 election that put the Conservative Party in charge, a reorganization moved responsibility for the salt campaign from one department to another, and interest flagged. Instead of pressuring industry to use less salt, the government and industry created a weak Public Health Responsibility Deal, and the campaign lost momentum.23 The government contended that the looser arrangement would be more effective and less costly. But the pace of declines in sodium consumption stopped declining, with researchers estimating that thousands more people each year between 2011 and 2025 would suffer cardiovascular disease.24

The effectiveness of the British campaign to reduce sodium is indicated by a survey of major fast food restaurants (Burger King, Domino’s, KFC, McDonald’s, Pizza Hut, Subway) in six countries.25 In 2012, researchers examined company nutrition information for more than 2,000 fast foods in Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Sodium levels across all the companies’ offerings averaged 25 percent higher in the United States than in the UK and 36 percent higher than in France, where the government also was pushing companies to cut the salt. For instance, in late 2019, Chicken McNuggets in McDonald’s home country had 150 percent more sodium than in the UK. Burger King Onion Rings had over six times as much sodium in the United States. And Subway’s Italian B.M.T. sandwich had 17 percent more sodium in the United States than in the UK.26 Yet some fast foods had more sodium in the UK while others, such as the Big Mac, had equal amounts.

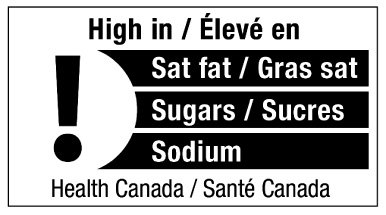

More than 70 countries have followed Britain by setting targets—usually voluntary, a few mandatory—for sodium levels in certain foods (table 7.1).27 But several countries are taking a different approach. They are requiring foods with more than a specified level of sodium (and calories, sugar, and saturated fat) to bear prominent warning labels on the fronts of packages (see figure 7.2).28 Chile was the first country to require warning labels as part of a broader program to encourage healthier diets beginning in childhood. Its labels are stop sign–shaped and state simply “high in sodium” or other nutrient. If a food is high in more than one of those nutrients, the label must show two, three, or four warning notices. Also, Chile has banned unhealthy foods from school cafeterias, limits cartoons on packaging, taxes sugar drinks, and restricts junk-food advertising on television.

Peru, Mexico, and Uruguay adopted labels like Chile’s. Israel has required similar warning icons to steer consumers away from foods high in sugar, salt, or saturated fat (though not calories), and also created a voluntary “healthy food” icon to attract people to healthier foods. Brazil is considering warning labels,29 as is Colombia.30 In 2018, Health Canada proposed four options for a warning notice, but that measure has been at least temporarily shelved.

Front-of-package warning notices can be much more effective than the Nutrition Facts labels used in the United States—which (for starters) are not placed on package fronts with recognizable icons but rather appear in small print on the side or back, and usually list more than a dozen nutrients. But numbers alone do not highlight problem nutrients in terms people can easily grasp, such as “high in sodium.” The Chilean health minister Carmen Castillo said the new law has had “a tremendous impact on public health.”31 Before the legislation took force, she said, businesses rushed to reformulate one-fourth of processed foods. A study published in 2020 found that sales of beverages high in sugar or other problem nutrients declined by 24 percent after the labeling and advertising law was passed, but the net change in calories from all beverages purchased was only 7.4 per day (that study did not include beverages sold at restaurants).32 In another recent report from Chile, University of Chile researchers found that sales of sugary breakfast cereals dropped by 11 percent and sugary juices by almost 24 percent.33

Figure 7.2

Front-of-package warning labels. Top: Chile’s labels for foods high in sugar, calories, saturated fat, and sodium; middle: Israel’s “healthy food” symbol and warning labels for foods high in sugar, sodium, and saturated fat; bottom: one of several formats that Canada has considered.

Lowering salt in packaged foods, by fiat or bolder labeling, may work in countries like Britain and Finland where most people rely on packaged foods and eating out. But several billion people around the world still cook most of their meals from scratch at home. In India, about 85 percent of salt comes from salt used in cooking and at the table.34 In contrast, Americans get only about 10 percent of salt that way. Health officials in cook-at-home countries need to devise novel ways to reduce sodium consumption. Because people buy packages of salt, one promising approach is for stores to offer products in which one-third or so of the sodium chloride is replaced by potassium chloride, a salt not quite as salty as table salt (see the section titled “Potassium Salt and Other Tricks of the Lower-Sodium Trade” in chapter 9). A drawback is that “lite salt” is more expensive and would have to be subsidized by the government in order to encourage people to choose it.

While other countries from Turkey to Chile are using a variety of means to lower sodium levels, until recently it has been talk and argument, not action, in the United States. We can only wonder how warning labels on foods, strict limits on sodium, or even voluntary limits, if adopted years ago, might have prevented thousands of strokes and heart attacks. I discuss in the next chapter how tough it has been to improve American salt policies.