Erik Angelone, Kent State University

Perspectives of Students and Professionals on Translation Theory: During Training,

After Training, Without Training

Abstract: This paper reports on the results of a corpus-based study of discourse rendered by student and professional translators in relation to fundamental aspects of translation theory and practice. Patterns of variation and overlap are outlined as grounds for optimizing translator training.

1. Introduction

In the 1990s, several scholars posited convincing reasons for the formal study of translation theory, largely in an attempt to establish a more direct connection between theory and practice. Gile, for example, emphasizes how theory can facilitate the translator by providing frameworks for analyzing alternative actions and their respective repercussions (1995, 13). Nord stresses theory as a means for justifying one’s translation choices (1997, 118). Nevertheless, many professionals continue to regard the study of theory as a “waste of time”, while students might see a course in theory as “an academic hoop they are required to jump through” (Shuttleworth 2001, 498).

Whether embraced, written off as superfluous, or met with ambivalence, theory has directly or indirectly shaped the academic discipline of Translation Studies, not unlike the manner in which practically any formal academic discipline is theoretically informed. Integration of theoretical content into the Translation Studies curriculum can take a number of different forms, including specific translation theory courses, theoretically-guided translation practice courses, and interdisciplinary courses in applied linguistics. Regardless of the extent to which theory is emphasized in translator training, as Katan highlights, translation theory and professional practice are far from symbiotic, instead dialectically representing a “great divide” (2009).

The study presented in this paper follows up on preceding survey-driven research on the relationship between theory and practice, as rendered through the respective discourses of translation students and professionals. Three different populations took part: 1) M.A. students who completed the survey while enrolled in a Translation Theory course in their first semester of the program at Kent State←67 | 68→ University, 2) B.A. and M.A. students currently completing coursework in Translation programs at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences who do not take a specified course in Translation Theory per se, and 3) professional translators who earned an M.A. in Translation from Kent State University, took the Translation Theory course, and have now been working in the field for a minimum of three years. Survey questions (outlined in the methods section) gauged participant perspectives on several pertinent dimensions of applied theory. In a very broad sense, this study explores the “great divide” between theory and practice from the perspective of deviations and overlaps in discourse. At a more granular level, it is hoped that discourse patterns will shed light on the following questions: How are notions of theory conceptualized when students do and do not formally take a translation theory course? Do conceptualizations regarding theory change after students graduate and enter the world of work? If so, to what extent and in which regards?

2. Gauging perspectives

In following up on recent studies that gauged the perceptions of students and professionals regarding the place and function of theory in training and on-the-job contexts (Orozco 2000; Katan 2009), the study described in this paper also examines what these two populations of translators have to say about issues related to translation theory. In this case, the discourse representing “students” comes from two different groups, namely M.A. students at Kent State University who took a theory course at the time of survey completion and B.A. and M.A. students at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences who are not required to take a formal course in translation theory, but rather are introduced to theoretical concepts in text analysis and practice translation courses. The professional translators who responded to the survey are graduates of the M.A. in Translation program at Kent State University. They took a formal course in Theory and have been working as professional translators for a minimum of three years.

2.1. Methods

The three aforementioned populations of translators were asked to respond to the following three survey questions:

1) What do you feel is the most important reason for studying translation theory?

2) Which competency (from a list of provided competencies) would you emphasize the most during an interview for an in-house translator position and why?←68 | 69→

3) What, in your opinion, distinguishes the expert translator from the professional translator?

To establish a sense of quantitative balance, the surveys of 27 participants were included as a representative sample for each of the three populations. Using WordSmith Tool’s1 WordList application, lexical frequency data was retrieved in order to document what participants tended to talk about on a consistent basis.

2.2. Results and Discussion

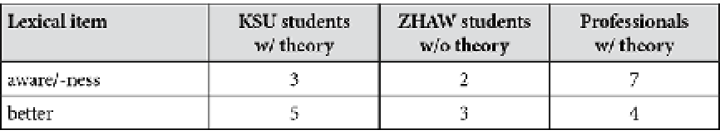

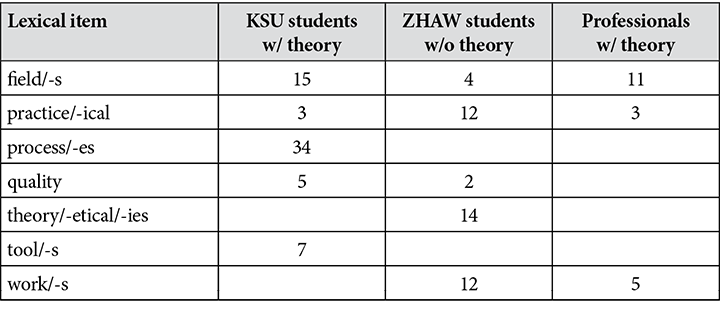

Table 1: Collective discourse patterns involving collocates for ‘theory’.

All three populations frame theory as important, albeit for different reasons. The two student populations establish a direct connection between theory and practice based on documented collocate patterns. The professionals, on the other hand, make no direct mention of ‘practice’ as an immediate collocate for ‘theory’. Perhaps they are simply less inclined to regard their source of income as ‘practice’, particularly in the academic sense likely implied by the students. The KSU M.A. students, through their use of the lexical items ‘proper’ and ‘science’, would seem to foreground theory from a Translation Studies “academic” lens.

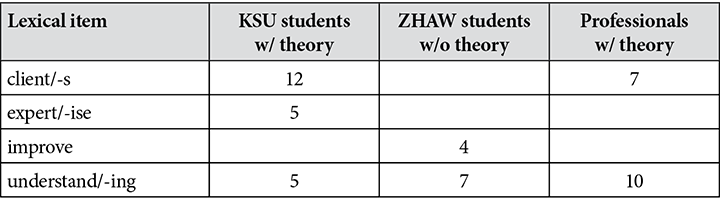

Table 2: Discourse patterns for survey question #1: Why study theory?

In their discussions of the important reasons for studying theory, the KSU students made frequent mention of ‘client’, suggesting their conceptualization of theory as a mechanism for client education in general and as grounds for explaining and justifying their work. The professionals also make mention of ‘client’ relatively frequently, suggesting that this, in fact, a real-world trend within the language industry. Discourse patterns also indicate that the KSU students regard theory as a means for reaching ‘expertise’. The professionals do not seem to see any potential correlation between theory and expertise, as the two are not mentioned in conjunction with each other in their discourse. All three populations seem to be of the opinion that studying theory is inherently advantageous based on the documented frequencies for ‘better’ and ‘improve’.

The three populations, and the professionals in particular, repeatedly mention ‘understand/-ing’ and ‘aware/-ness’ in the context of important reasons for studying theory, pointing towards a certain level of enhanced cognizance of the translation task at hand brought about by theoretical understanding.

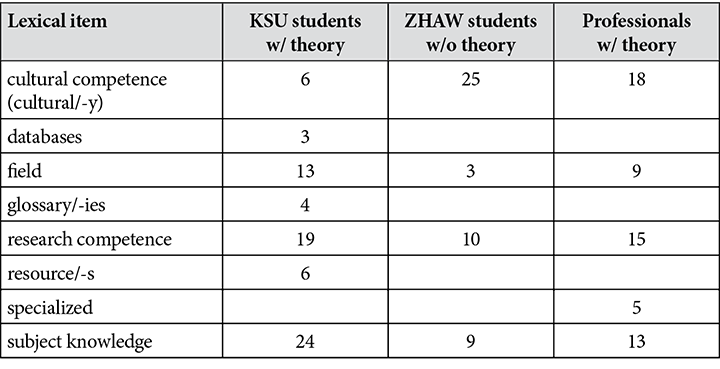

Table 3: Discourse patterns for survey question #2: Most important competence?

All three populations consistently stress research competence, perhaps as a means for filling gaps in other competency areas. The importance placed on sound information retrieval is reverberated through frequent mentioning of ‘resource’, ‘glossary’, and ‘databases’ in the KSU student discourse. Subject competence, or lexical items that are semantically associated with it (‘subject knowledge’, ‘field’, ‘specialized’), is much more pronounced in the discourse of KSU students and professionals. This may be the result of the still-pervasive mentality in mainstream U.S. society that bilingual subject experts are on equal footing with formally trained translators. ‘Terminological competence’ and ‘terminology’, at a combined frequency of 49, is by far the most represented competence in the KSU student discourse, yet hardly appears in the other two discourse sets. This may reflect what the KSU students find to be particularly challenging when translating texts, and, in turn, a tendency to process texts at more of a sub-sentential level. ZHAW students call attention to ‘textual competence’ instead of terminological competence, suggesting a more firmly-rooted understanding of the importance of supra-sentential aspects like genre and text-type conventions. The ZHAW students and professionals stressed the importance of ‘cultural competence’ and ‘cultural/-y’ in their responses to the second survey question. From the professional’s perspective in particular, this would seem to highlight the fact that culturally-relevant content is a rich point even in the most technical of fields.

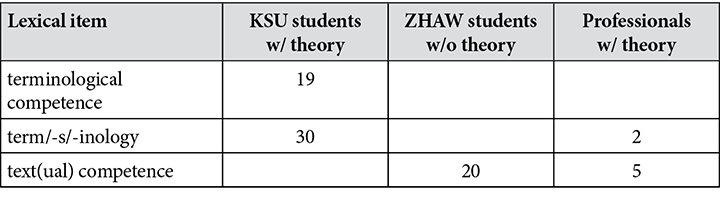

Table 4: Discourse patterns for survey question #3: What distinguishes the expert from the professional?

Perhaps not surprisingly, all three populations made frequent mention of ‘experience’, ‘practice’, and ‘work’ in their discussion of parameters that distinguish the expert from the professional. The KSU students and professionals, in particular, emphasize knowledge in a given ‘area’ or ‘field’ as a pre-requisite for expertise. The professionals are more than likely specialized in a given domain, whereas the KSU students only had a few classes in specialized translation (as opposed to non-translation oriented coursework in a particular field). Interestingly, the latter also holds true for the ZHAW students, yet their mentioning of a given field or area in conjunction with expertise was much lower in frequency.

Interestingly, only the KSU students make frequent mention of ‘quality’ in their discourse on expertise. In striving for improvement in the formal grades they receive for their translations in an academic context, students might naturally come to regard this as a metric par excellence in any attempt to assess level of expertise. In this age where “good enough” depends on so many variables that go into a given translation project, such as deadlines, rates, and directionality, the expert translator may very well not be one who produces top-quality translations (whatever that might imply), but rather one who is the most productive given the constraints and demands of the given task at hand. This productivity, in turn, might be shaped in large part by some of the things the professionals mention in their discussion of expertise, such as ‘self-criticism’, which becomes particularly important in the real-world of translation given the fact that feedback on quality from others is often scant. The KSU students frequently mention ‘tool/-s’ in conjunction with expertise. Efficacious use of tools from the perspective of cognitive ergonomics, as currently being researched in a series of workplace studies (Ehrensberger-Dow and Massey 2014), may very well distinguish the expert from the professional.←72 | 73→

Another interesting trend that emerges is the tendency for only the ZHAW students to propose awareness of ‘theory’ as a trait that distinguishes the expert from the professional. On the one hand, this might come across as somewhat surprising given the fact that these students do not formally take a course in translation theory during their studies. However, perhaps these students see the direct impact and benefits of theoretical knowledge in the context of practice and text analysis courses, where it is introduced in a very applied manner.

3. Future directions: Optimizing theoretical training

In addition to documenting similarity and variation in discourse patterns across the three populations, a fundamental underlying objective of this research is to utilize gained insights for optimizing theoretical training. It is hoped that a preliminary examination of the following might provide trainers with food for thought in this regard.

3.1. What all three populations tend to emphasize regarding theory

One of the few things on which all populations seem to agree is the importance of theoretical awareness. The notion of using theory to enhance understanding of the translation task is a common and consistent message. In other words, theory provides a much-needed guiding light. Also interesting is the consistent focus of all three groups on both subject competence and research competence as important translation competencies. In light of this, perhaps trainers, if they are not already doing so, could make a deliberate effort to gear theoretical instruction in the direct of these competencies. For example, going over sound information retrieval skills in a concrete fashion might go a long way in theoretical discussions centered around such concepts as the translation commission, the concept of a parallel text, and, by extension, functionalist approaches to translation in a broad sense.

3.2. Aspects professionals emphasize and students do not

A central message found in the discourse of the professionals but not elsewhere is the idea of utilizing theory for purposes of making choices in translation. In their opinion, theoretical awareness would seem to foster the skill of being able to pick and choose from an array of theories based on the specific, changing constraints of translation tasks. With this in mind, trainers involved in the teaching of practice courses might want to consider setting up activities where students must select←73 | 74→ from a range of theoretical models as a pre-translation strategy for guiding their work. For that matter, it might be interesting for students to explore how the very same text can be translated in a number of different ways based on the application of various approaches.

3.3. Changes in the opinions of professionals from the time of their studies

The most noticeable departure in the discourse of the professionals from the discourse they generated as students involves a deliberate shift away from aspects of terminology and terminological competence in responding to what they feel is the most important competence. During their time as students at KSU, these individuals were definitely exposed to a great deal of terminologically-oriented training. However, perhaps the professionals are now so well-versed in the use of term bases that terminology is no longer considered to be particularly challenging vis-à-vis other challenging aspects of translation in which they are maybe not as well-versed.

In closing, it is crucial to examine what the professionals tend to discuss instead when it comes to important competences. Interestingly, it is in this context where we see overlap between the discourse of the professionals and the discourse of the ZHAW students. Both groups foreground cultural competence and textual competence as essential. Curricular change should be rooted in language industry demands that may very well deviate from ivory tower ideals. It would seem as if cultural competence and textual competence could serve as central pillars in tweaking or re-shaping theory training and translator training at large in a much-needed industry-informed fashion.

References

Ehrensberger-Dow, M. / Massey, G. (2014): Cognitive Ergonomic Issues in Professional Translation. In: Schwieter, J. / Ferreira, A. (eds.): The Development of Translation Competence: Theories and Methods from Psycholinguistics and Cognitive Science. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 58–86.

Gile, D. (1995): Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Katan, D. (2009): Translation Theory and Professional Practice: A Global Survey of the Great Divide. In: Hermes 42, 111–154.

Nord, C. (1997): Translation as a Purposeful Activity: Functionalist Approaches Explained. Manchester: St. Jerome.←74 | 75→

Orozco, M. (2000): Building a Measuring Instrument for the Acquisition of Translation Competence in Trainee Translators. In: Adabs, B. / Schäffner, C. (eds.): Developing Translation Competence. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 199–214.

Shuttleworth, M. (2001): The Role of Theory in Translator Training: Some Observations about Syllabus Design. In: Meta 46/3, 497–506.←75 | 76→ ←76 | 77→

1 For more information, see http://www.lexically.net/wordsmith/.