Judith Mudriczi, Budapest Business School

In Quest of ‘Uncommon Nonsense’: The Hungarian Translations of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Abstract: The paper contrasts the Hungarian translations of Alice in Wonderland in the 20th and 21st centuries. Studying the different renderings of the Mock Turtle motif in the four most prominent Hungarian versions illustrates why Hungarian readers do not find this work as amusing as the English text.

1. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland as a Key Cultural Text

The cultural significance of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, first published in 1865, is undeniable. In the past 150 years, it has been published in 7,600 editions and translated into 174 languages (Lindseth 2015, 13). From a theoretical point of view, this work exemplifies what translation studies scholar Kirsten Malmkjaer calls “key cultural text” (2015, npn.) This term covers texts that play a significant role in the representation of a particular culture and in defining its cultural others. The culture-bound elements of these texts pose a challenge to translators, who cannot ignore their implication of and embedding in the source culture even if they are rather difficult to transfer to the target language. Cultures substantially differ, for instance, in their understanding of basic notions like childhood and adulthood or freedom and personal identity, which has its consequences for the wording of the target language versions of translated texts. Translation scholars benefit from studying these versions as they reveal the reasons behind the difficulties of translation and also offer explanations for the linguistic and social dynamism of the need for retranslations of key cultural texts.

This paper offers an overview on the most prominent Hungarian translations and retranslations of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, then contrasts the different renderings of a particular culture bound element, the motif of the mock turtle, to illustrate why Hungarian readers find this work less amusing than its English original.←163 | 164→

2. Hungarian Translations and Retranslations in the Twentieth Century and Today

Since the first Hungarian translation of the book published in 1927, 61 Hungarian versions and adaptations have appeared in print (Kérchy 2015, 294.). 15 of these were translated before 1989, while 46 were published afterwards, which reflects a growing interest in this work in Hungarian intellectual circles even today. Studying all these versions would move beyond the scope of this paper, which narrows its interest to the four most significant ones.

One of the earliest translations, Alisz kalandjai Csodaországban [Alisz’s Adventures in Wonderland] published in 1929, has been almost completely deleted from the cultural memory of Hungarian people. This lack of recognition is partly due to the fact that the books of its translator, Andor Juhász, were prohibited for being ideologically dangerous to the Soviet regime according to a 1945 government decree. Nevertheless, based on the catalogue entries of the National Széchényi Library, he was a prolific translator of English, German, French and Russian literary works in the 1920–30s but the circumstances and historical setting of his translation of Carroll’s book are unknown.

Évike Tündérországban [Evie in Fairyland], the 1936 translation by the renowned author Dezső Kosztolányi, has also had an unfortunate reception history, but in this case it was due to the strong domesticating tendencies of the Hungarian version. The translator was a member of the literary circle known as the Nyugat generation whose translation practice did not demand a strong correspondence between the source text and the target text. To recall Kosztolányi’s wording: “It is not possible, and not allowed, to demand faithfulness to the letter from the literary translator. Because faithfulness to the letter is unfaithfulness as languages differ in their material” (Szilágyi 2012, 92). Hungarian scholar András Kappanyos explains Koszolányi’s domesticating practices in their social context and rightly claims the following:

There is a comprehensive and specific system of cultural assumptions in the Alice books: […] the world of Alice is the well refined and strongly localized cultural universe of a sophisticated and wealthy 10-year old girl in the Victorian era. The book is based on the customs, social types, linguistic turns and, most relevantly, literary texts that the idealized Alice knew […] Kosztolányi in fact replaced this system of cultural references by substituting Hungarian counterparts for the external references to an assumed piece of knowledge in the source culture (2013, 208–209). [my translation]

This approach is manifest for instance in his translation of the title as Évike Tündérországban; Alice is given a popular Hungarian name and “wonderland” becomes fairyland, a term completely comprehensible for juvenile readers. Kosztolányi’s←164 | 165→ domesticating creativity was so strong that John Tenniel’s illustrations had to be replaced by Dezső Fáy’s drawings so that they could match the specific wording of the Hungarian translation.

The translation that has proved to be the most influential in Hungary was published in 1958. The book entitled Alice Csodaországban [Alice in Wonderland] was in fact Tibor Szobotka’s revision of Dezső Kosztolányi’s translation but even today many people believe that this version is Kosztolányi’s work. The need for retranslation of the 1936 version could have emerged for many reasons. Ildikó Józan believes that Szobotka found the revision necessary not only because the characters and the story had been culturally modified but also because the poems had been considerably different in the English and Hungarian versions (2010, 225). Another plausible explanation is based on the fact that in accordance with the strongly centralized cultural policy of the era, many popular translations had to be reassessed and reworked in the 1950s. These retranslations were ideologically supervised and even the translators themselves were carefully chosen as “being a translator was considered a privilege and as such only the best – or the most prestigious – could partake of it as far as state-controlled publications were concerned” (Szilágyi 2012, 96–97). Tibor Szobotka obviously belonged to the favoured ones, since his career skyrocketed after 1957, the year when the “policy of the three P’s” (prohibited, permitted or promoted) was announced (Kontler 1999, 445). Not only was Szobotka offered a permanent position at the World Literature Department of Budapest University but both he and his wife, Magda Szabo, also started enjoying all the benefits of “being promoted” in literary circles. However, due to the lack of historical records, it is still unknown why he was asked to revise Kosztolányi’s translation. Regardless of its reasons, the outcome of his work has been reasonably criticised by many scholars. András Kappanyos summarizes the changes as follows:

While Kosztolányi consistently followed an undoubtedly disputable concept in his translation, Szobotka’s revision with its numerous contradictions hindered the reception of the book in Hungary; its macrostructure on the whole reflects an foreignizing ranslation strategy, but in the case of smaller details, Kosztolányi’s wording, which had been in accordance with the domesticating strategy applied in the 1936 text, were left unchanged (214). [my translation]

Ildikó Józan fiercely attacks Tibor Szobotka’s revision, which, in her opinion, intends to give a more literal translation of the work at the expense of its dramaturgy and the flow of Kosztolányi’s Hungarian adaptation (Józan 228). She also highlights that Szobotka, besides harming Kosztolányi’s image as a translator, also made the text of Carroll’s book incomprehensible and puzzling for many←165 | 166→ generations of Hungarian readers (236). Regardless of its content and quality, this translation has gained the widest recognition since its publication in 1958 due to the fact that it has been reprinted 18 times and also used for many theatrical and audiovisual adaptations.

As the interpretive strategies and the readers’ expectations have changed, a new Hungarian version of the book entitled Aliz kalandjai Csodaországban és a tükör másik oldalán [Aliz’s Adventures in Wonderland and on the Other Side of the Looking-glass] was published in 2009. This translation by Dániel and Zsuzsa Varró was made upon the publisher’s request so that the new Hungarian text considers biographical references in the source text and more properly matches John Tenniel’s illustrations to appeal even to younger readers. The translators, of course, knew the existing versions of the text but thought that the mistakes and mistranslations in the Kosztolányi-Szobotka versions derived from the fact that these translators did not seem to take the English source text seriously or simply did not respect the source text at all. Therefore the Varró brother and sister disregarded all previous Hungarian versions and produced their own translation of the text with historical, literary and philological considerations in mind (Elekes 2011, npn.).

3. The Mock Turtle and its Hungarian Counterparts

There are many scenes in the book where Alice encounters some forms of nonsense but one of the most memorable is her meeting with the Mock Turtle. It is the Queen of Hearts that asks her whether she has seen the Mock Turtle, the thing from which Mock Turtle Soup is made. Then the Gryphon takes her to meet the Turtle and listen to his story, which, in fact, is an account of the subjects he learned at school. The scene also includes the performance of the lobster quadrille and ends with Alice and the Gryphon running off to a trial while the Mock Turtle is singing the Turtle Soup song. The Queen of Hearts’ reference to the soup and the Turtle Soup song itself provide a frame of culinary references to the presence of the turtle motif in the plot. Mock turtle soup is a thick greenish soup that is made with beef instead of turtle. John Tenniel’s illustration visualizes this ambivalence by hiding a calf’s head, legs, hooves and tail in a turtle shell. Translating his name as well as his story in the book provides Hungarian translators and readers with an enormous challenge as Hungary is not a seaside country. Thus Hungarian culture and language do not abound in an extensive vocabulary of oceanography, which makes the translation of the names and puns of sea animals extremely difficult in the target language. Nevertheless, the culinary reference is a bit more fortunate, as the famous Hungarian goulash has a special version called “hamis gulyásleves”←166 | 167→ [mock goulash soup], which is made with vegetables instead of beef. Nevertheless, only the 1929 and 2009 Hungarian translations seem to reflect the use of this culinary counterpart in the target language. The following table summarizes the presence of the turtle motif in the Hungarian translations discussed above.

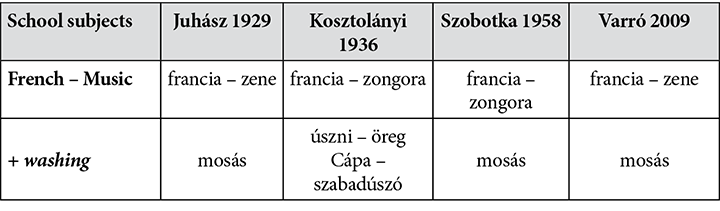

This table clearly shows even for those who do not speak Hungarian that Kosztolányi’s version disregards most references to the turtle and the soup and simply deletes this puzzling cultural element. Readers who speak Hungarian will also notice that in the 1936 version the culinary reference completely disappears since “Tengeri Herkentyű” means ‘some weird sea creature’, which epitomizes how Kosztolányi’s domesticating translation strategy turns the nonsense pun into a less amusing and semantically flat Hungarian expression. This simplification is also present when the Mock Turtle lists the subjects he learned at school. The next table shows the English puns and their Hungarian counterparts in the different translations.

Except for the word “angolna”, the Koszolányi and Szobotka versions do not apply any water-related terminology but in most cases simply look for words of movement that are homophonous with the names of school subjects. The table also shows that among the four versions, the one from 2009 is the most faithful to the English original and also the most amusing one. What many readers may find a bit surprising is that Andor Juhász’s translation from 1929 reflects an attitude←168 | 169→ that is very similar to our present-day understanding of translation norms. Had it not been unavailable for so long, Hungarian readers most probably would find Carroll’s book more amusing and interesting even today. Although the cultural memory of Hungarian people has established the 1958 version as the most canonical, which firmly created an image of Carroll’s book as a difficult and strange piece of writing, the most recent translation by the Varró sister and brother has the potential of modifying and replacing this impression.

The contrastive study of the available Hungarian translations of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland highlights that the target language versions strongly depend on the different views of translation and also on the expectations of the historical and social context in which they are produced. At the same time, the overview of the reception history of the book in Hungary also proves that regardless of the extent of textual correspondence between the source and target language versions, the judgment and reception of a key cultural text primarily depends on the particular social and cultural forces that dominate the target culture in a particular historical period.

References

Carroll, L. (1958): Alice Csodaországban, trans. Kosztolányi, D. rev. Szobotka, T. Budapest: Móra.

Carroll, L. (1929): Alisz kalandjai Csodaországban, trans. Juhász, A. Budapest: Béta Irodalmi Rt.

Carroll, L. (2009): Aliz kalandjai Csodaországban és a tükör másik oldalán, trans. Varró, D. / Varró, Zs. Budapest: Sziget.

Carroll, L. (1936): Évike Tündérországban, trans. Kosztolányi, D. Budapest: Gergely.

Elekes, D. (2011): A gyerekek is szeretik a jó szöveget, a jó mondatokat. Meseutca. Available at http://meseutca.hu/2011/12/13/a-gyerekek-is-szeretik-a-jo-szoveget-a-jo-mondatokat-2/ (Retrieved March 2015).

Józan, I. (2010): Nyelvek poétikája. Alice, Évike, Kosztolányi meg a szakirodalom és a fordítás. In: Filológiai Közlöny 2010/3, 213–238.

Kappanyos, A. (2015): Bajuszbögre, lefordítatlan. Műfordítás, adaptáció, kulturális transzfer. Akadémiai doktori értekezés, Budapest: Balassi.

Kérchy, A. (2015): Essay on the Hungarian Translations of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. In: Alice in a World of Wonderlands: Translations of Lewis Carroll’s Masterpiece. Vol. 1. Lindseth, J. / Lang, M. (eds.). New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, USA, 2015. 294–299.←169 | 170→

Kirsten Malmkjaer, K. (2015): Key Cultural Texts in Translation. Unpublished manuscript.

Kontler, L. (1999): Millennium in Central Europe. A History of Hungary. Budapest: Atlantisz.

Lindseth, J. (2015): Editorial Note. In Alice in a World of Wonderlands: Translations of Lewis Carroll’s Masterpiece. Vol. 1. Lindseth, J. / Lang, M. (eds.). New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, USA, 2015. 13–14.

Szilágyi, A. (2012): Invisible Authors and Other Illusionists: Hungarian Translation in the First Half of the Twentieth Century. In: eSharp 19, 78–100. Available at http://www.glasgowheart.org/media/media_247025_en.pdf (Retrieved March 2015).←170 | 171→