Pawel Sickinger, Universität Bonn

The Root of All Meaning: Embodied,

Simulated Meaning as the Basis of Translational Equivalence

Abstract: This paper discusses cognitive equivalence, a new attempt at defining translational equivalence in a substantiated, psychologically realistic fashion, exemplified by an empirical study triangulating expressions in German, English and Japanese via their perception-based conceptual representations.

1. Revisiting equivalence from a cognitive perspective

The issue of equivalence is one of the classic problems in translation theory, and it has always been at the core of debates about both the nature of translated texts and a potential basis for translation quality assessment (see Pym 2010 for a detailed overview; cf. Pym 2009). Over the last decades, however, the very concept of equivalence has fallen into disgrace with various strands of translation theoreticians, either in the form of a downgrade to a minor factor, as proposed e.g. in Skopos theory (Reiss / Vermeer 1984), or in more extreme cases as a call for abolishing the concept altogether (see e.g. Snell-Hornby 1988; Holz-Mättanari 1990). A common theme underlying these critiques is the accusation that the concept is ill-defined, or even entirely vacuous (see Snell-Hornby 1988), and that it has so far failed to advance translation studies as a whole and should be abandoned in favor of researching other aspects of translation. Rising to the challenge, a number of translation scholars have attempted to defend the concept, often from the viewpoint of comparatively traditional, text-focused approaches to translation analysis – Juliane House’s work is especially relevant in this context (see e.g. House 1997). Overall, however, interest appears to have shifted away from the equivalence debate in favor of more recently introduced topics and frameworks (see Pym 2009).

I would argue, though, that there is a solid case to be made for reconsidering equivalence and the role it can play in translation theory now. New incentives for readdressing this issue have emerged, not from inside translation theory, but rather coming from other areas of research on language, communication and mind that yet have to be properly introduced to the relatively self-enclosed world of translation studies. Developments in fields external to the traditional reach of←245 | 246→ translation studies, namely in cognitive linguistics, cognitive psychology, theories of embodied cognition and embodied meaning, have brought exciting new approaches and methods that in my view can substantially alter the playing field for translation theory. What has changed in these fields over the last three decades is important to virtually all issues discussed in translation studies, primarily because it entails new perspectives on the nature of language, its representation in human minds and the way it is processed by human beings.

It may not be surprising that translation studies has by and large ignored these developments, given that its major theoretical ‘turns’ have shifted the attention towards socio-cultural and poststructuralist perspectives on translation (see Snell-Hornby 2006 for an overview). Early attempts to merge translation theory with a cognitive perspective, initially based on relevance theory (Gutt 1991), have failed to achieve a lasting impact with the majority of translation scholars (cf. Smith 2002). And while the formation of a cognitive translation studies has been foreshadowed by the work of a small number of researchers more recently (see e.g. Halverson 1999; Risku 2000), so far their efforts appear to lack a coherent direction as well as a shared basis, apparent e.g. in major discrepancies about what is meant by the label “cognitive”.

Working in both translation studies and cognitive linguistics, I think that the innovations in the scientific areas mentioned above could substantially advance translation studies as a field, and particularly help us finally come to terms with the Gordian knot that the concept of equivalence turned out to be. In the following, I will briefly describe an experiment that I have conducted in the context of my PhD thesis, and then show how it relates to some of the fundamental questions in translation theory. I will then proceed to introduce my concept of cognitive equivalence, which is a revised variant of Nida’s dynamic equivalence (Nida 1964), and argue that it is compatible with both classic notions of equivalence and more recent theoretical innovations in translation studies, namely House’s concept of translation as a “third space” (House 2008).

2. The meaning of “bald” – an empirical study on triangulating lexical meaning across languages

In the empirical study that I want to briefly describe here, I have looked at translational equivalence from a slightly different angle, asking whether it is possible to establish degrees of equivalence across languages in a way that goes beyond the intuitive knowledge of multilinguals and professional translators. Most importantly, my goal was to establish equivalence relations between expressions in different languages without relying on linguistic data in the process, so that circularity is←246 | 247→sues could be avoided. In as much as competent speakers of two given languages ‘know’ whether an expression in language A can be considered equivalent to another expression in language B, this cannot serve as the methodological basis of scientific inquiry, as it is the very phenomenon in need of scientific explanation. Relying on linguistic intuition in this fashion – as contrastive approaches such as Wierzbicka’s NSM (see e.g. Wierzbicka 1992) arguably do – merely reifies these intuitive judgments using scientific terminology, but fails to identify the underlying mechanisms responsible for producing these judgments.

In order to avoid this methodological pitfall, I designed an experiment centered on visualizations of a selected exemplary concept, in this case the concept (or mental model) of MALE BALDNESS. The method itself combines ideas from William Labov’s famous study of cup-like objects (Labov 1973) and more recent work by Dirk Geeraerts and colleagues concerned with semasiological and onomasiological variation (Geeraerts et al. 1994). In a reversal of Labov’s original approach, I used expressions from the lexical field of MALE BALDNESS (which I refer to as baldness terms) as linguistic stimuli, based on which informants were asked to design matching visual representations. To give an example, English speaking informants e.g. would read the sentence “He has a receding hairline.” and be asked to produce a visual representation that best matches the meaning of this expression as they understand it. To ensure that the resulting visual data would be comparable between informants, their design activity had to be rigidly controlled, in this case by having informants perform the task in a specifically created online environment that allowed the manipulation of the amount of hair on a schematically depicted male head via a simple user interface. The visual model manipulated by informants was directly based on an established chart used for medicinal diagnosis (Norwood 1975) to ensure that informants’ design efforts would produce realistic, natural results, whereas the pool of baldness terms used as stimuli was gathered in a series of interviews with native speakers of all three languages tested in the experiment.

This method was intended to provide insight into ordinary language users’ conceptual representation of MALE BALDNESS and the way that specific sub-regions of it are selectively activated by baldness terms in different languages. More specifically, I was interested in the internal structure of the conceptual category and its linguistic activation routes compared between English, German and Japanese, all of which have their respective means of referencing baldness phenomena via their language-specific inventory of baldness terms. The concrete aim was to capture the activation routes for a given language’s baldness terms in a non-linguistic←247 | 248→ format, resulting in a ‘mental map’ for the concept that, due to its independence from linguistic description, can be validly compared across languages.

For data analysis, visual representations created by informants were transformed into numerical values based on underlying visual features, resulting in a data point located in a two-dimensional metric space per informant and baldness term tested. The sum of data points related to the same stimulus can be interpreted as the visual-conceptual category for the corresponding baldness term, with a centroid marking the idealized center of the category. The corresponding findings are too specific and too complex to be reproduced in the present context. Exemplary results for the term “bald patch” can be seen in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Data obtained for baldness term USA 04.

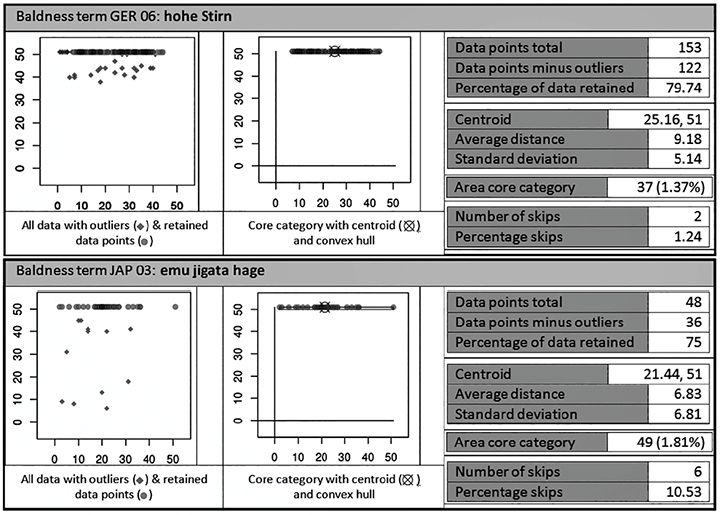

As all baldness terms tested in the experiments can be mapped onto the same metric space, their interrelations can be explicated in terms of distance functions between categories. More precisely, the relative size of an overlap between two given categories and the distance between their respective centroids function as a quantifiable measure of the overall degree of difference between their respective visual representations. In this sense the conceptual distance between two given terms becomes both visible and measurable across languages, allowing for a comparison of any pair of terms based on how conceptually similar they are to one another. A comparison of this kind can be seen in figure 2 below, showing the data obtained for a German and a Japanese baldness term that are highly similar according to this measure.

Admittedly, this method of establishing translational equivalence is relatively crude, not least because it is fully reliant on visual representations and deliberately disregards more complex, cultural layers of meaning that may play an important role in concrete translation problems. Furthermore, the exemplary concept in←248 | 249→ question was specifically selected due to its strong reliance on sensory data, and generalization from this case to other conceptual domains is not guaranteed to succeed. In my view, however, it nonetheless serves to show that establishing a measure of equivalence across languages is possible without recourse to linguistic description. Moreover, I do not consider this measure of equivalence an artifact of the experimental method used in my study. On the contrary, I have made specific efforts to design the experimental setup so that it reflects a basal cognitive process involved in comparing meaning across languages in multilinguals, including professional translators. Without going into detail about my model of translation processes here, the relevant premise is that the reception of source language material triggers conceptual activity in the translator that is, at its core, non-linguistic (i.e. a situation model or simulation, see e.g. Zwaan and Radvansky 1998; Barsalou 1999). Associative links from this conceptual level of text reception to linguistic units in the target language then invoke translation options to be contemplated by the translator in producing the target text. For this rendering of the translation process to make sense, however, embedding it in an embodied account of (linguistic) meaning is necessary.

Figure 2: Baldness term GER 06 and JAP 03 in comparison.

3. Embodied meaning and cognitive equivalence

The question at the heart of this issue is where we should look for the locus of linguistic meaning, both in the epistemological and the methodological sense. Adopting an embodied, cognitive perspective, I suggest that there is no independent, ‘Platonic’ realm in which the meaning of words, sentences or texts resides, but that these meanings are produced in the minds of human beings processing the linguistic units in question. Furthermore, this generation of meaning cannot take place in a linguistic domain, lest we risk running into the same circularity issues that I have cited above as a methodological problem. According to a number of renowned cognitive scientists and psychologists, language becomes meaningful when linguistic input activates conceptual structures based on sensory information and embodied experience, whether we call these structures simulators (Barsalou 1999), ICMs (Lakoff 1987) or mental models (Johnson-Laird 1983). Conversely, linguistic output is generated from activating such conceptual structures, scanning their contents and associatively co-activating corresponding linguistic units (see Barsalou 2012, 241). The conceptual domain forms the necessary background against which language can become meaningful, either as the source or the product of language processing (cf. the discussion of ‘grounding’ in Glenberg / Robertson 2000).

The question remains how this relates to translation theory, and particularly how it impacts on the question of translational equivalence. Firstly, I suggest that this general notion is not new to translation studies at all, but has been discredited for potentially invalid reasons. We can find a suggestive if somewhat flowery variant of it in Danica Seleskovitch’s theory of sense (see Seleskovitch / Lederer 1989), arguing for the existence of a language-independent layer of conceptual meaning that links source and target text. The central theme of linguistic meaning as residing in psychological processes of language reception is also clearly present in Eugene Nida’s famous concept of dynamic equivalence. Equivalence as defined by Nida and Taber is “the degree to which the receptors of the message in the receptor language respond to it in substantially the same manner as the receptors in the source language” (1969, 24). Nida’s approach has been criticized for various reasons, but I think it should be re-evaluated as a psychologically realistic account of the translation process that was ahead of its time in its focus on the cognitive effects of texts in reception.

What is missing from Nida’s account of equivalence, however, is the pivotal role that processes within the translator’s mind play in constituting the resulting translation, as opposed to reception processes in readers of translated and original texts. The latter only exert an indirect influence on actual translation decisions, whereas the translator’s cognitive processing is the locus of these decisions and should therefore be at the center of translation studies’ inquiries. This is why I propose the con←250 | 251→cept of cognitive equivalence instead (adopting the label and part of its meaning from earlier work by Nili Mandelblit, 1997). The central idea is that translators do not base their translation decisions on the reception effects in real-life recipients’ minds, but rather engage in the cognitive simulation of the effects of source and target text on imagined recipients. This is where equivalence in the procedural sense can be found: in the translator’s attempt to counterbalance differences between (virtual) source and target text recipients to establish equivalence between their respective conceptual effects. I am convinced that cognitive equivalence in this sense is the basic mechanism behind all decision making in translating (cf. Wilss 1990).

Support for this approach to translation and equivalence can, surprisingly, be found in more recent work by Juliane House, even if it takes a few interpretative steps to bridge the two perspectives. While House has traditionally been known to champion purely text-focused approaches to translation studies (cf. House 1997), the latest addition to her framework has a strikingly psychological tone to it. Her revised approach is centered on the notion of translation as a “third space phenomenon” (House 2008), which refers to a psychological domain where translation processes take place. In this realm

[…] the realization of a discourse out of a text available in writing then involves imaginary, hidden interaction between writer and reader in the mind of translator, where the natural unity of speaker and listener in oral interaction must be imagined in the face of real-world separateness in space and time of writer and reader (2008, 156).

I read this as a cognitive account of translation, where the less vivid interaction with purely linguistic entities is, in the mind of the translator, transformed into a communicative interaction with imagined recipients, allowing for a feedback loop that in reality does not exist. This is exactly what I aim for with the concept of cognitive equivalence: In my view the translator is engaged, incrementally, in two such imaginary communicative interactions, one with source text readers and one with target text readers. The act of establishing equivalence between target and source text then becomes the act of balancing divergences in the reactions of these two groups, aiming towards an ideal equilibrium that in reality will probably not be attained. And as the source text is already fixated and cannot be sensibly manipulated to optimize this balance, the natural solution is to consider different target text options until a satisfying degree of similarity is reached. This is the kind of equivalence that my empirical study is supposed to make visible, and this is the kind of thinking about translational equivalence and translation processes that I suggest translation studies as a whole needs to become attuned to. None of this will be possible without adopting a psychological realistic, cognitive perspective on translating, even if this in turn means breaking with some respected traditions and convictions.←251 | 252→

References

Barsalou, L.W. (1999): Perceptual Symbol Systems. In: Behavioral and Brain Sciences 22, 577–660.

—.(2012): The Human Conceptual System. In: Spivey, M. / McRae, K. / Joanisse, M. (Hgs.): The Cambridge Handbook of Psycholinguistics. New York, 239–258.

Geeraerts, D. / Grondelaers, S. / Bakema, P. (1994): The Structure of Lexical Variation. Meaning, Naming, and Context. Berlin/New York.

Glenberg, A.M. / Robertson, D.A. (2000): Symbol Grounding and Meaning: A Comparison of High-Dimensional and Embodied Theories of Meaning. In: Journal of Memory and Language 43, 379–401-

Gutt, E.-A. (1991): Translation and Relevance: Cognition and Context. Oxford.

Halverson, S. (1999): Conceptual Work and the ‘Translation’ Concept. In: Target 11/1,

1–31.

Holz-Mänttärri, J. (1990): Funktionskonstanz – eine Fiktion? In: Salevsky, H. (Hg.): Übersetzungswissenschaft und Sprachmittlerausbildung: Akten der ersten internationalen Konferenz Übersetzungswissenschaft und Sprachmittlerausbildung. Berlin, 66–74.

House, J. (1997): Translation Quality Assessment: A Model Revisited. Tübingen.

—.(2008): Towards a Linguistic Theory of Translation as Re-contextualization and a Third Space Phenomenon. In: Linguistica Antverpiensia 7, 149–175.

Johnson-Laird, P.N. (1983): Mental Models: Towards a Cognitive Science of Language, Inference and Consciousness. Cambridge, MA.

Labov, W. (1973): The Boundaries of Words and their Meanings. In: Bailey, C.-J.N. / Shuy, R.W. (Hg.): New Ways of Analyzing Variation in English. Washington D.C., 340–373.

Lakoff, G. (1987): Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. Chicago.

Mandelblit, N. (1997): Grammatical Blending: Creative and Schematic Aspects in Sentence Processing and Translation. Dissertation, University of California, San Diego. Online: http://www.cogsci.ucsd.edu/~faucon/NILI/contents.html.

Nida, E.A. (1964): Toward a Science of Translating: With Special Reference to Principles and Procedures Involved in Bible Translating. Leiden.

Nida, E.A. / Taber, C.R. (1969): The Theory and Practice of Translation. Leiden.

Norwood, O.T. (1975): Male Pattern Baldness: Classification and Incidence. In: Southern Medical Journal 68/11, 1359–1365.

Pym, A. (2009): Western Translation Theories as Responses to Equivalence. Unpublished. Innsbrucker Internationale Ringvorlesung zur Translations←252 | 253→wissenschaft, Universität Innsbruck, March 12, 2008. N. pag. Online:

http://usuaris.tinet.cat/apym/on-line/translation/2009_paradigms.pdf.

—.(2010): Exploring Translation Theories. London/New York.

Reiss, K. / Vermeer, H.J. (1984): Grundlegung einer allgemeinen Translationstheorie. Linguistische Arbeiten 147. Amsterdam.

Risku, H. (2000): Situated Translation und Situated Cognition: ungleiche Schwestern. In: Kadric, M. et al. (Hg.): Translationswissenschaft. Festschrift für Mary Snell-Hornby zum 60. Geburtstag. Tübingen, 81–91.

Seleskovitch, D. / Lederer, M. (1989): Pédagogie raisonnée de l’interprétation. Bruxelles-Luxembourg.

Snell-Hornby, M. (1988): Translation Studies. An Integrated Approach. Amsterdam/Philadelphia.←253 | 254→ ←254 | 255→