Naoko Kito, University of Vienna

The Role of Personal Pronouns and Forms of Address: Implicature in English and Japanese

Abstract: The aim of this paper is to demonstrate how pragmatics-based translation could contribute to traditional translation studies by investigating personal pronouns and forms of address in English and Japanese. My research shows a significant interaction between language and culture.

1. Introduction

The world has been extended and globalized, and accordingly the role of translation has become more and more significant and complex. Nowadays language users expect more than just surface meanings which have always been the focus of traditional linguistic disciplines. We are now aware of intercultural differences, which make us realize the limits of language-based translation. The importance of pragmatics, a study of language in use, has been emphasized by many scholars (Grice 1975; Leech 1983; Mey 2001; Verschueren 1999) and the field of translation is no exception.

Personal pronouns and forms of address have been regarded as a simple phenomenon in language. Yet, in terms of translation, they sometimes show a great difficulty due to their complex culture-specific features and it is particularly significant when languages representing different language systems and cultural backgrounds are compared.

The aim of this paper is to demonstrate how pragmatics-based translation could contribute to traditional translations studies by investigating personal pronouns and forms of address in English and Japanese.

2. Personal Pronouns in English and Japanese

Personal pronouns in English, among many Indo-European languages, are basically categorized into 1st, 2nd, and 3rd persons which have singular and plural forms. As many grammar books show, the Japanese translations are as in Table 1.←263 | 264→

Table 1: Comparison of English German and Japanese Personal Pronouns.

The Japanese may, however, realize in everyday conversation that these Japanese personal pronouns are not exactly equivalent to neither the English nor German pronouns. The use of a second person pronoun is particularly limited different from those in the other two languages. Anata is regarded as the translation of the formal form of you in English or Sie in German. Nevertheless, although it sounds polite in isolation, it sounds impolite in everyday utterance. That is to say, although it semantically has a polite property, anata pragmatically triggers an impolite implicature. Moreover, as regards kimi, its use is not the same as you in English nor du in German. Kimi is likely to be used by a superior when addressing an inferior, but not between friends, for example. The use of personal pronouns in Japanese is therefore highly dependent on the situation and the context. In other words, in an utterance in Japanese, it is highly important for the addresser to know whether the addressee is superior or inferior, distant or close, or older or elder. Only under these conditions, the Japanese can properly communicate.

In English, the center of the system of personal pronouns is I as Karl Bühler (1934) insists with his theory of ORIGO. First and second person pronouns in English only show the abstract roles of interlocutors, such as I am a speaker and you are a hearer. They do not present concrete features, such as age, social status or gender. In Japanese, on the other hand, I can first be defined only with help of the others.

3. Forms of Address in English and Japanese

Forms of address in Japanese are much wider than in English. John Smith, for example, can be referred as shown in Table 2.←264 | 265→

Table 2: Forms of Address in English and Japanese.

|

English |

Japanese |

|

Mr. Smith, John, nickname, social role (e.g. Doctor) |

Smith, John, nickname, family name + -san (e.g. Smith san), first name + -san (e.g. John san), first name+ -chan (e.g. John chan), Smith + social role (e.g. Smith sensei), Social status (e.g. sensei) |

Now, I would like to have a closer look at social roles as forms of address.

(1) Matsumoto-san ha dou omoware masu ka? (very formal)

[Matsumoto Pol. how think Pol. Pol.Que.]

“What does ‘Mr./Mrs. Matsumoto’ think?”

(2) Sensei ha dou omoware masu ka? (very formal)

[Teacher how think Pol. Pol. Que.]

“What does ‘teacher’ think?”

(3) O-kyaku-sama ha dou omoware masu ka? (very formal)

[Pol.customer Pol. how think Pol. Pol. Que.]

“What does ‘customer’ think?”

(4) O-nei-chan ha dou omou? (informal)

[Pol.elder sister Inf. how think]

“What does ‘elder sister’ think?”

Examples (1)–(4) illustrate different ways of addressing. In English, names are only used to refer to the third person and not to the addressee. In Japanese, on the other hand, names are basically used for both the third person and the addressee. When the superior social status of the addressee is obvious, referring to him/her by his/her name is regarded as impolite and people prefer to use social roles as forms of address to show respect. For example, when (1) Matsumoto-san ha dou omoware masu ka? (What does ‘Mr./Mrs. Matsumoto’ think?) is directed to a teacher, it can evoke implicature, such as “I don’t accept that you are a teacher, so I don’t want to call you a ‘teacher’”.

4. Analysis from a Japanese Film Script

4.1. Plot: Sekai no Chūshin de, Ai wo Sakebu (2004) (Crying out Love, in the Center of the World)

In 1986, in a small town in Oita, southern Japan, two high school classmates, Saku and Aki, fall in love. However, Aki confesses that she suffers from leukemia. Leukemia weakens her and she dies after asking Shige-ji, the owner←265 | 266→ of a photo studio, to take a photo of her in a wedding dress with Saku. Young Ritsuko frequently visits her mother in hospital where she meets Aki. She brings tapes, Aki’s audio diary, to Saku for her. When Ritsuko brings the final tape to Saku, she has a car accident and the tape is not delivered. The story begins when Ritsuko, who is Saku’s fiancée by 2003, finds an old tape in Tokyo 17 years later.

4.2. Analysis

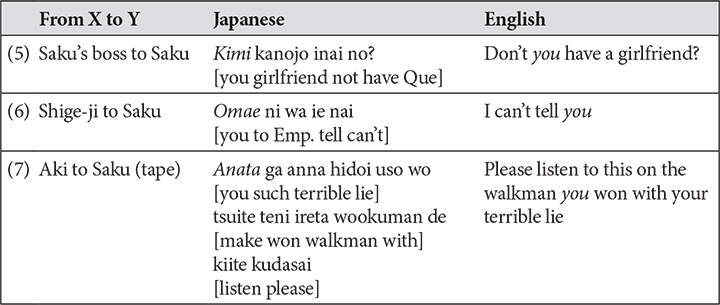

Table 3: Examples of Personal Pronouns ‘You’. Examples from Sekai no Chūshin de, Ai wo Sakebu (2004).

Examples (5)–(7) in Table 3 show a significant linguistic difference between English and Japanese. Anata (formal), kimi (less formal) an omae (informal), all ‘you’ in English, are differently used depending on the situation. Firstly, one of these pronouns is intentionally selected depending on the social role of addressee the addressee. Kimi in (5) is directed to Saku by his boss and it represents the higher social status of his boss. Secondly, pronouns are used depending on the addresser’s aim of conveying some implicature, as in (7) Anata. The speaker Aki is angry about Saku’s lie and deliberately selects anata, a formal form of ‘you’. It stands for her remoteness, which is reinforced by her speaking in a polite way. In (6), on the other hand, omae shows bluntness or curtness of the addresser. In English, all of these three pronouns are translated as ‘you’, from which the implicatures yielded in Japanese are absent.←266 | 267→

Table 4: Example of Forms of Address ‘You’. Examples from Sekai no Chūshin de, Ai wo Sakebu (2004).

In the Japanese original script, we clearly see the change of the relationship between Saku and Aki by realizing the change of forms of address from (8) Hirose, the addressee’s family name, to (9) Aki, her first name. This change proves the implicature such as “I got closer to Aki” or “Aki is my girlfriend”. In English, however, (8) Hirose is translated simply as ‘you’ and the implicature, which is clearly evoked in Japanese, is absent.

5. Analysis from an English Film Script

5.1. Plot: Sex and The City 2 (2010)

Carrie Bradshawis is the main character together with her best friends: Samantha Jones, Charlotte York Goldenblatt and Miranda Hobbes. They live in New York and each of them has problems which women are familiar with in their lives. Carrie realizes she looks at marriage from a different perspective than her husband Big, whom she has been married to for two years. Samantha is an independent businesswoman and enjoys her single life and sexual relationships. She is paranoid about getting old and indulges in a lot of youth enhancing tablets and uses a wide range of cosmetics every day. Charlotte has two children, Lily and Rose, with her Jewish husband Harry. She is eager to have an ideal family, but is worried about a sexual relationship between the cute and young nanny Erin and Harry. She is also sometimes seized with an impulse to get away from the children. Miranda is a lawyer and lives with her husband Steve, her child Brady and the babysitter Magda. She suffers from sexual discrimination at the hands of her new senior partner at the firm.←267 | 268→

5.2. Analysis

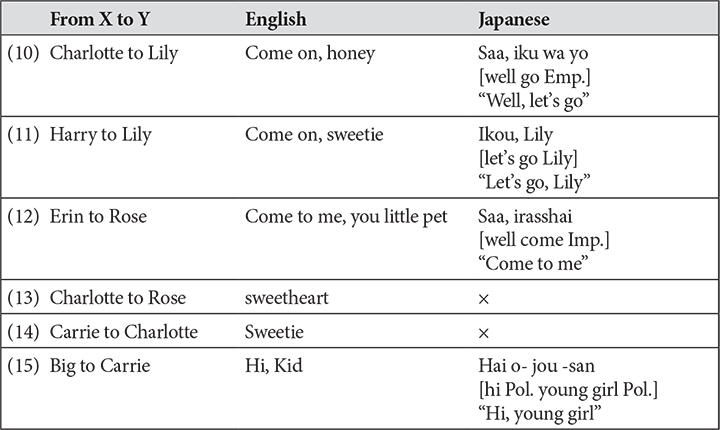

Table 5: Examples of Forms Endearment. Examples from Sex & The City 2 (2010).

Comparing the English and Japanese scripts, the most significant feature is terms of endearment. As the examples in Table 5 show, English has a rich vocabulary of terms of endearrment which implies a close relationship. (10) Honey, (11) & (14) sweetie, (13) sweetheart, and (15) kid are typical English forms of endearment which stand for closeness between the addresser and the addressee. Forms of endearment can also be creative, as in (12) you little pet. In the previous chapter, I presented that forms of address in Japanese are much wider than in English. Nevertheless, the analysis shows that forms of endearment are exceptions.

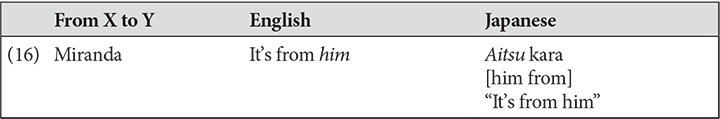

In Table 6 a personal pronoun evokes a particular meaning in Japanese.

Table 6: Example of Personal Pronoun ‘Him’. Examples from Sex & The City 2 (2010).

Him in (16) is translated into a particular pronoun in Japanese which brings about a certain meaning. Aitsu in (16) is usually directed at a person whom the addresser has a negative image of or whom the addresser dislikes. Him and aitsu, therefore,←268 | 269→ cannot be considered exact translation equivalents, even though the referential range of the two lexical items would appear to coincide. Considering the context, the Japanese translation aitsu is even better in that it conveys implicature by which we naturally understand that Miranda has a negative image of ‘him’. In English, the personal pronoun ‘him’ itself does not evoke any particular implicature and contextual knowledge is more important than in the Japanese translation in order to follow the story properly.

6. Conclusion

Personal pronouns and forms of address are one of the most significant examples in translation which shows a close relationship between language and culture and it is very important to consider a culture-specific role of personal pronouns and forms of address for a correct translation. Since pronouns exist almost in every single sentence, a pragmatically wrong translation may give the addressee completely different interpretations.

The analysis shows that Japanese is richer than English in terms of their personal pronouns while English is richer than Japanese in terms of forms of endearment. This presents that one language is richer in one category while another language is richer in another category. Therefore, a word-for-word translation is often impossible and it is important than anything that one keeps pragmatic differences in different languages in mind when translating.

It is a big challenge in translation to consider how those shared culture-specific assumptions can properly be conveyed in another language, to which a pragmatic-based translation will make a great contribution.

References

Grice, P. (1975): Logic and Conversation. In: Cole, P. / Morgan, J.L. (eds.). Syntax and Semantics 3. New York.

Leech, G. (1983): Principles of Pragmatics. London.

Mey, J.L. (2001): Pragmatics (2nd ed.). Oxford.

Verschueren, J. (1999): Understanding Pragmatics. London.

Bühler, K. (1934): Sprachtheorie: Die Darstellungsfunktion der Sprache. Jena.

Sekai no Chūshin de, Ai wo Sakebu (2004) Video. Prod. and dir. by Isao Yukisada. Toho. (Film).

Sex & The City 2. (2010) Video. Prod. and dir. by Michael Patrick King. Warner Bros. (Film).←269 | 270→ ←270 | 271→