IN our discussion of the chronology of Paul’s life, his initial ministry in Macedonia was dated between September 48 and April 50, the two years being equally divided between Philippi and Thessalonica.1 There I emphasized that one year in each place was the absolute minimum; it is entirely possible that Paul stayed longer. The two Macedonian churches were perhaps the communities that gave Paul the greatest happiness. The divisions which marred other foundations were virtually non-existent. More importantly, the quality of their communal life made them stand out as beacons of life and hope (1 Thess. 1: 6–8; Phil. 2: 14–16). They were apostolic in precisely the way he wished, and generous to a fault (2 Cor. 8: 1–4). If they had assimilated his teaching so well, he must have spent a considerable time among them.

This fact is the decisive refutation of Luke, for whom Paul spent only three weeks in Thessalonica (Acts 17: 2) before being hounded out by Jewish agitators (Acts 17: 5–10). In addition to the considerations just mentioned, such a short visit is explicitly contradicted by the character of his initial letter (1 Thess. 2: 13–4: 2). The profound affection and confidence therein displayed argues unambiguously for a prolonged acquaintance.2 This is confirmed by Philippians 4: 16 in which Paul thanks the Philippians for the financial aid they sent him more than once after he had left them to minister in Thessalonica.3 His gratitude for such subsidies, despite the fact that he had found work (1 Thess. 2: 9; 2 Cor. 3: 8), indicates an extended and successful ministry. The hours he had to devote to new converts eroded his income, and to live he needed financial support from elsewhere.

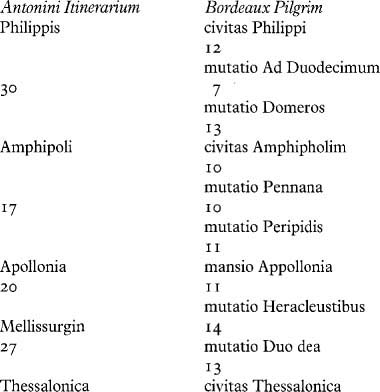

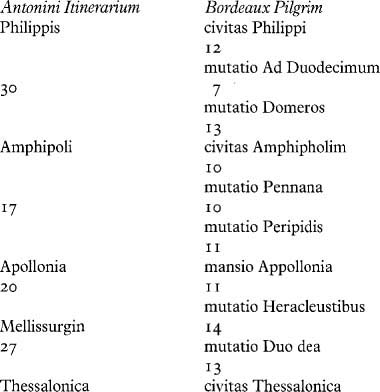

Philippi and Thessalonica were linked by the Via Egnatia, which ran from the Adriatic Sea to the Bosphorus (see Fig. 7).4 Leaving Philippi Paul followed it to the west, as did the Bordeaux Pilgrim on his way back from the Holy Land in AD 333. The latter gives the distances in Roman miles, as does the Antonini Itinerarium, but in the opposite direction.5 The following list summarizes their data:

Manifestly the list of the Bordeaux Pilgrim is the more complete, because it told the dispatch riders where they could change horses (a mutatio) and ordinary travellers where they could find lodging for the night (in a civitas or a mansio). His distances are also more realistic.6 Normally one would expect to get from one civitas/mansio to another in one day’s march. As a general rule only one mutatio intervenes. In this section there are two, giving stages of 32, 31, and 38 Roman miles. These are unusually long, as are three others going west out of Thessalonica, and may suggest that travellers were expected to make good time on this part of the road. The Philippians, therefore, were only three days’ good walking away from Paul in Thessalonica. To stay in touch and and to respond to his needs was not difficult. A round trip could be made in a week.

With Paul’s ministry in Thessalonica I shall deal in a moment, because it is known only as reflected in letters written later. Here the question of why Paul left Thessalonica demands attention. Luke blames it on the hostility of the Jewish community there, but this cannot be taken at face value. It could be true, but Luke elsewhere invokes it as an explanation when it is demonstrably false, e.g. Paul himself tells us that the Nabataeans caused his hasty departure from Damascus (2 Cor. 11: 32–3), but for Luke the Jews were responsible (Acts 9: 23–5).7 Moreover, the only hostility documented by Paul in Thessalonica came from Gentiles. The majority of the community was of pagan origin (‘you turned to God from idols’, 1 Thess. 1: 9), and the persecution they suffered originated with ‘your own countrymen’ (1 Thess. 2: 14).8 The implication of 1 Thess. 3: 1–3 is that this persecution had begun before Paul left, and it is the simplest explanation of his departure.

It is not impossible, as some have argued, that when Paul moved west along the Via Egnatia from Philippi to Thessalonica his plan was to follow the great highway to its terminus on the Adriatic coast where it would have been easy to find a boat for Italy and Rome (Rom. 15: 23).9 Had he to flee because of trouble with the municipal authorities in Thessalonica, however, it would have been most imprudent to stay on the main road. He needed to get to an area where the municipal writ did not run, particularly if the authorities had invoked Roman assistance.

Strabo’s description of Macedonia in book 7 of his Geography is preserved only in fragments, in one of these (frag. 10) the Via Egnatia is identified as the southern border of the Roman province. This is certainly wrong. A whole array of indicators combine to fix that border on average some 70 km. south of the Via Egnatia.10 The most efficient escape route for Paul would have been a ship to bring him south into a different Roman province, Achaia. Thus there may be a historical reminiscence in Luke’s note that Paul headed for the coast after further trouble in Beroea (Acts 17: 14).11 Be that as it may, Paul safely made it to Athens (1 Thess. 3: 1; Acts 17: 15), where he was able to take breath and to reflect on the situation of his converts at Thessalonica.

The New Testament contains two letters to the Thessalonians. Some scholars, however, claim they were originally one missive, whereas others detect four letters.12 I am obliged, therefore, to try to justify my own view of the letters because it underpins my historical reconstruction.

A characteristic feature of all Pauline letters is the thanksgiving; it immediately follows the address and subtly and indirectly introduces the main themes of the letter.13 1 Thessalonians stands out among the letters of Paul in that it contains two thanksgivings.14 Even a quick reading reveals the close similarities between 1: 2–10 and 2: 13–14. Schubert disputes the fact that there are two thanksgivings, maintaining that formally the one thanksgiving of 1 Thessalonians runs from 1: 2 to 3: 10, and in fact constitutes the body of the letter.15 Not only is his argument from form confused and implausible, but it has been contradicted on both formal16 and rhetorical grounds.17 Moreover, the vast majority of commentators, who divide the letter on thematic principles, limit the first thanksgiving to 1: 2–10.18 Finally, if 1: 2 to 3: 10 was in fact intended to be an unusually long thanksgiving, one would expect Paul to heap up different reasons for gratitude. This is not the case, which doubles the abnormality of the reiterated thanksgiving form.

Schmithals also discerned two conclusions in 1 Thessalonians, namely 3: 11 to 4: 2 and 5: 23–8.19 In fact the former contains a number of elements normally found in the concluding portion of a Pauline letter. The desire to see the recipients (3: 11) is found in 1 Cor. 16: 5; 2 Cor. 13: 10; and Philem. 22. The prayer in 3: 12–13 has a very close parallel in 5: 23. The phrase ‘finally believers’ (4: 1) is evocative of 2 Cor. 13: 11; Phil. 4: 9; 2 Thess. 3: 1; cf. Gal 6: 17.

Such data permits only one conclusion. An originally independent letter, 2: 13 to 4: 2 with its own thanksgiving and conclusion, has been inserted into another letter constituted by 1: 1 to 2: 12 and 4: 3 to 5: 28. In other words, 1 Thessalonians as it now stands is a compilation of two letters. This phenomenon is not unique among the Pauline letters, it is also to be observed in Philippians (three letters) and 2 Corinthians (two letters).20 Inevitably when two letters are combined one or both are truncated, because the beginning and/or ending become superfluous, if the fiction of a single letter is to be preserved. Thus it is not surprising that 2: 13 to 4: 2 lacks both the address and the elements which constitute the normal ending of a Pauline letter, namely, the peace wish, the greetings, and the grace-benediction.21

Before appealing to the contents of the two letters for confirmation of this conclusion, a preliminary question must be dealt with. Why was 2: 13 to 4: 2 inserted into the middle of 1: 1 to 2: 12 and 4: 3 to 5: 28 rather than being attached to the end of the letter, as 2 Cor. 10–13 was appended to 2 Cor. 1–9? The similarity between 2: 11–12 and 4: 1–2 guaranteed that 4: 1–2 would integrate perfectly with the list of directives (4: 3–12) which originally followed 2: 11–12. The match was even better between 2: 12 and 2: 13 because the ‘call’ of God in the former is taken up in the latter by ‘the word of God which you heard from us’. At both ends, therefore, the harmonization was too neat not to be capitalized upon. Hence, the impression of a single letter.

If I Thessalonians is in fact two letters, which came first? Here the judgement is necessarily much more subjective, but I think that a serious case can be made for the priority of 2: 13 to 4: 2, which in consequence I call Letter A.

This letter is permeated by a profound sense of relief. Paul had been deeply worried (2: 17) that persecution (2: 14) would force the Thessalonians to abandon Christianity (3: 2–3, 5, 6, 7). He had wanted to come to their aid personally, but had been prevented (2: 17). Instead he sent Timothy (3: 2), and the good news the latter brought of the steadfastness of the Thessalonians (3: 6) was the cause of the joy Paul now experienced (3: 9), and the occasion of this letter.

The whole tone of Letter A suggests that it was Paul’s first communication with the Thessalonians since his flight. It originated in his need and was not a response to any communication from the Thessalonians. The persecution, which had begun prior to Paul’s departure, remained his major preoccupation. His uncertainty with regard to the outcome is the sole explanation of the emotionally charged language of virtually every verse. Letter A is precisely the sort of letter one would have expected Paul to write in reaction to Timothy’s good news, whereas 1 Thessalonians in its present form definitely is not. Some commentators see an allusion to persecution in 1: 6. This is not at all certain.22 If it were, however, it is psychologically impossible that such a detached reference to persecution should belong to the same letter as the desperate involvement implied by the allusions in Letter A. Paul, it should be emphasized, dealt immediately with what was uppermost in his mind, e.g. the defection of the Galatians (Gal. 1: 6) and the lack of unity among the Corinthians (1 Cor. 1: 10). That he should here restrain his emotional response to the fidelity of the Thessalonians for two whole chapters would be totally out of character. Moreover, his vision of them is so rosy that their steadfastness became sufficient evidence of their moral probity. The euphoric optimism of Letter A’s ‘just as you are doing’ (4: 1) stands in vivid contrast, not only to the tone of Letter B but to its list of ethical directives in 4: 3–8, and especially to its hints that all is not well in the community (5: 13–14). Other differences will come to the fore when we discuss Letter B in detail.

What time-interval should we postulate between Paul’s leaving Thessalonica and writing Letter A? The time he spent worrying before sending Timothy into danger cannot be computed with any precision, but Paul’s ardent temperament repudiated procrastination, and I doubt that more than two weeks should be allowed. The distance between Thessalonica and Athens is roughly 500 km. (320 miles).23 This figure must be tripled in order to include Paul’s flight south, and Timothy’s round trip to Thessalonica and back. Sixty days would be necessary to cover 1,500 km. (960 miles) at an average of 25 km. (16 miles) per day. Hence a minimum of some ten weeks must have elapsed before Paul got Timothy’s good news. His anxiety certainly had plenty of time to intensify.

In the interval Paul preached at Athens. His ministry was not a success. His silence regarding any converts confirms the basic thrust of Luke’s account in Acts 17. It is not impossible that Paul’s distracted state—his preoccupation with the fate of Timothy and the Thessalonians—contributed to his failure at Athens. His anxiety inhibited the wholeheartedness that effective preaching demands.

1 Thessalonians 3: 1 is usually understood to imply that Paul had already left Athens when the letter was written,24 but this is in no way demanded by either formulation or context. The interpretation is inspired by a conscious or unconscious desire to harmonize Letter A with Acts 17: 15 and 18: 5. Common sense, on the contrary, suggests that Paul’s profound anxiety obliged him to remain where Timothy would be able to find him without any difficulty. Were Timothy’s return route known (he could have come by land or sea), Paul’s reaction would have been to move north to meet him as soon as possible, as he did on another occasion, when he was equally anxious for news brought from Corinth by Titus (2 Cor. 2: 12–13). It is out of the question that Paul should have delayed his reunion with Timothy, by going in the opposite direction, towards Corinth, a strange city in which Timothy would have had enormous difficulty in finding him.25

There is no doubt that Paul eventually moved from Athens to Corinth, but only after he had been joined by Timothy. The move is noted by Luke (Acts 18: 1), and confirmed by 2 Corinthians 1: 19 which puts the three co-authors of Letter B (Paul, Timothy, and Silvanus) in Corinth during Paul’s founding visit there. It is difficult to say with certitude why he made the move. Two linked reasons, however, can be suggested. Corinth offered advantages which Athens lacked, and these facilitated Paul’s missionary planning.

Up to this point Paul gives the impression of merely wandering west, with Rome perhaps as the vague long-term objective. Once he had established a community he felt free to move on, leaving its development to the guidance of the Holy Spirit. The situation at Thessalonica, however, forced him to recognize the need (both his and theirs) to stay in contact with his foundations. Thus for the first time he had to think in terms of a base, which, at the minimum, had to fulfil two conditions; it must be relatively easy to establish a church there, and communications with the surrounding area must be excellent.

In the mid-first century these conditions were met much more satisfactorily at Corinth than at Athens. The latter was an old sick city whose past was infinitely more glorious than its present.26 The implications of the delicately nuanced description of the city by Strabo27 are spelled out succinctly by Pausanias, ‘Athens was badly hurt by this war with Rome, but flowered again in the reign of Hadrian.’28 The contrast drawn by Horace between the quiet of Athens and the tumult of Rome highlights its lack of vitality.29 Athens was no longer either productive or creative. Essentially a mediocre university town dedicated to the conservation of its intellectual heritage, it viewed new ideas with reserve. Tradition, enshrined in a rigid hierarchy, was its one safeguard against the threat of novelty. As a centre of learning it had been surpassed even by Tarsus.30 The poverty of its economy is shown by the dearth of new buildings.

Corinth, on the contrary, was a wide-open boomtown. San Francisco in the days of the California gold rush is perhaps the most illuminating parallel. The decision of Julius Caesar in 44 BC to re-establish the city, which his precedessors had sacked a century earlier, was motivated by the legendary character of the city as ‘wealthy’.31 The new colony quickly justified his expectations, and within two generations it had become the most important trading centre in the eastern Mediterranean. All its wealth was new money. Even those who in Paul’s time had inherited riches were close enough to their origins to know where it came from. In opposition to the complacency of Athens, Corinth questioned. It was still a city of the self-made, and lived for the future. New ideas were guaranteed a hearing, not necessarily because of intellectual curiosity, but because profit could be found in the most unexpected places.

This atmosphere was to Paul’s advantage. He must also have been aware that the establishment of a church at Corinth would carry weight elsewhere as an argument for the value of Christianity. The proverb ‘Not for everyone is the voyage to Corinth’ was widely known.32 The bustling emporium was no place for the gullible or timid; only the tough survived. What better advertisement for the power of the gospel could there be than to make converts of the preoccupied and sceptical inhabitants of such a materialistic environment (cf. 2 Cor. 3: 2)?

Over and above such advantages, Corinth offered Paul both outreach and superb communications with all points of the compass. It was one of the great crossroads of the ancient world and, even if we discount the flowery language, the praise lavished on Corinth by Aelius Aristides contains a great deal of truth, ‘[Corinth] receives all cities and sends them off again and is a common refuge for all, like a kind of route or passage for all humanity, no matter where one would travel, and it is a common city for all Greeks, indeed, as it were a kind of metropolis and mother in this respect’ (Orations 46. 24).

Traffic in, out, and through the city was intense. It stood on the land bridge linking Greece to the Peloponnese. Boats shuttled between Asia and Europe. Paul had the possibility of influencing people from a great variety of different areas, and converts could carry the gospel back to their own people. Travellers going in all directions offered some security for Paul’s messengers.

Paul tells us nothing about his founding visit to Corinth, with the exception of the fact that he was accompanied by Silvanus and Timothy (2 Cor. 1: 19; cf. Acts 18: 5). All that can be deduced from his letters regarding his relations with the church there belongs to a later period and will be dealt with in the context of the Corinthian correspondence, which is also the appropriate place to deal with the information provided by Luke in Acts 18: 1–22. It must suffice here to note that he lodged with Prisca and Aquila, from whose home he wrote his next letter to the Thessalonians, namely, Letter B.

This letter (1: 1 to 2: 12 and 4: 3 to 5: 28) makes no allusion to persecution. A calm didactic tone replaces the effervescent warmth of Letter A. Compliments are doled out carefully instead of being scattered broadside. More importantly, Paul’s attention is no longer entirely concentrated on the Thessalonians. His image among members of the community has become a major preoccupation, if we are to judge by its position in the letter immediately after the thanksgiving (2: 1–12). When his focus again shifts back to the Thessalonians, it is to spell out the demands of Christian living (4: 3–12; 5: 12–22), and to deal with issues concerning the Day of the Lord (4: 13 to 5: 11).

Particularly noteworthy in Letter B is the complete evaporation of Paul’s desire to see the Thessalonians. This is easily explained if his affectivity has acquired a new object. Evidently he has become progressively more absorbed in the nascent Corinthian community. He recognizes his continuing responsibility for the church at Thessalonica, but it is no longer his primary concern. The emotional distance between Letter A and Letter B implies that some considerable time separates them.33

This inference is confirmed by indications in Letter B that there have been contacts between the churches of Thessalonica and of Corinth independently of Paul. The existential witness mentioned in 1: 7–8 (‘you became an example to all the believers in Macedonia and in Achaia … your faith in God has gone forth everywhere, so that we need not say anything’) demands direct contact. Thessalonians who came south could only speak of the exemplary quality of their community life (cf. 4: 9); it became visible only to Corinthian believers who went north.34 It is these latter who reported to Paul how favourably he was still remembered at Thessalonica (1: 9; cf. 3: 6). Presumably it was they who also brought the information with which he deals in the body of the letter.

Whereas the authenticity of 1 Thessalonians is accepted without question, that of 2 Thessalonians is still a matter of debate. For a significant number of scholars it was written, not by Paul, but by one of his followers towards the end of the first century.35 They invoke differences of style and vocabulary, but in a highly selective way which prejudges the conclusion. When used objectively, however, such evidence proves that 2 Thessalonians is more at home in the Pauline corpus than 1 Thessalonians or 1 Corinthians.36 The cold impersonal tone of 2 Thessalonians is often contrasted with the warmth of 1 Thessalonians. In reality, however, there is a much greater difference in tone between Letter A and Letter B (see above) than there is between the latter and 2 Thessalonians.

Ever since the synoptic presentation of 1 and 2 Thessalonians by W. Wrede,37 it is generally agreed that the strongest argument against the authenticity of 2 Thessalonians is its identity of structure and often of language with 1 Thessalonians. Such an extensive overlap, we are told, is unlikely in a single author, but a forger would tend to copy the framework and vocabulary of 1 Thessalonians in order to enhance the credibility of a different eschatological vision of which 2 Thessalonians is the vehicle. The validity of this conclusion and the observations on which it is based have not gone uncontested.

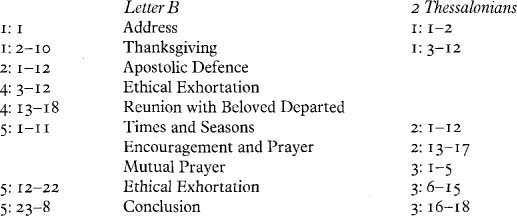

The argument from the sequence of material is drastically weakened by a glance at the actual arrangement of the two letters, even when Letter A, which has no parallel in 2 Thessalonians, is removed:

If we exclude the address, thanksgiving, and conclusion, which are the most stereotypical features of all Pauline letters, the argument from sequence boils down to the fact that ‘Times and Seasons’ is followed at some point by ‘Ethical Exhortation’.38

The arguments against the authenticity of 2 Thessalonians are so weak that it is preferable to accept the traditional ascription of the letter to Paul. In this case, the most natural explanation of the similarity of order is that circumstances forced him to return to the same subjects, and we know that it was his custom to deal with doctrinal points before turning to exhortation. It should be unnecessary to emphasize that in treating identical issues it is inevitable that the same language should reappear.

At this point we must confront the question of the order of Letter B and 2 Thessalonians. It has been argued that 2 Thessalonians antedates 1 Thessalonians,39 but once again the reasoning is anything but apodictic; dubious observations are given forced interpretations.40 2 Thessalonians, on the other hand, contains one objective argument showing that it is posterior to Letter B. In 2 Thessalonians 2: 15 Paul writes, ‘So then, believers, stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught either by word of mouth or by letter.’ The meaning is unambiguous; the preaching of Paul has been supplemented by a previous letter.41 Since Letter A contains nothing that can be described as ‘traditions’, there can be little doubt that the allusion is to Letter B. Confirmation of this conclusion is provided by 2 Thessalonians 3: 17, ‘I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand. This is the mark in every letter of mine.’ The implication is that the Thessalonians had at least one other letter from Paul. Even though the Apostle does not identify himself in 1 Thessalonians 5: 27, the sudden appearance of the first-person singular suggests the handwriting of the author guaranteeing the work of his secretary.42 By drawing attention to this feature of his letters Paul gave the Thessalonians the criterion to distinguish his authentic letters from forgeries.

Whether Paul consciously envisaged the possibility of forgery is not absolutely certain. Some have deduced it from 2 Thessalonians 2: 2,43 but Bruce’s observation on this verse deserves to be quoted,

The particle hôs does not definitely deny the writers’ authorship of the epistle in question: the misunderstanding may or may not have arisen from an epistle, and if it has so arisen, the epistle may or may not be authentic. If the reference is to an authentic epistle (and the genuineness of 2 Thessalonians itself be accepted), we should have to think of a misunderstanding of 1 Thessalonians.44

This insight has been exploited most effectively by Jewett.45 He discerns a series of five passages in 1 Thessalonians, which he considers were susceptible of misinterpretation by the Thessalonians. Three of them (1 Thess. 2: 16, 18; 3: 11–13) appear to me to be rather implausible, and moreover belong to what I have called Letter A. He has perceptively recognized, however, that two texts from Letter B easily lend themselves to misunderstanding.

The first is ‘You yourselves know that the day of the Lord comes as a thief in the night’ (1 Thess. 5: 2). Manifestly Paul intended his words to be understood in a future sense, but the present tense ‘comes’ could be read by those in a fever of intense eschatological expectation as meaning that the day of the Lord had already arrived but secretly. This interpretation would be facilitated by a diminution or cessation of persecution which, in opposition to Letter A, is not mentioned at all in Letter B. Those who wanted to believe could have seen a momentary halt in persecution as a sign of Christ’s all-powerful presence among them. This line of reasoning, or something very similar, is necessary to explain why the Thessalonians believed that the day of the Lord had come (2 Thess. 2: 2).

Paul also laid himself open to misunderstanding by writing ‘God has not destined us to wrath but to obtain salvation through our Lord Jesus Christ who died for us so that whether we wake or sleep we might live with him’ (1 Thess. 5: 9–10). The main clause is ‘God has destined us for salvation’. What God decides, however, will necessarily take place. The Thessalonians could legitimately conclude, therefore, that their salvation was guaranteed. The corollary was equally obvious. How they lived was irrelevant, because nothing that they did could modify the divine decision. They could even find explicit justification for this further deduction in the phrase ‘whether we wake or sleep’. Paul intended this to mean ‘whether we are alive or dead’ (cf. 1 Thess. 4: 13–15). But just previously in this context he had used the same words in a different sense, ‘Let us not sleep as others do, but let us keep awake and be sober’ (1 Thess. 5: 6), which encouraged the interpretation ‘whether we are vigilant or careless’, namely, with respect to moral observance.

Those whose words have been misunderstood will have little difficulty in identifying with the mystified irritation with which Paul would have reacted to such reports of what he was supposed to have said in Letter B. Whatever the explanation—honest misunderstanding, deliberate distortion, forgery—it was not something that he could afford to let pass. He had to react, and did so with somewhat icy clarity in 2 Thessalonians. As Jewett has noted,

The addition of new material in 2 Thessalonians, designed to clarify the nature of the eschatological signs that must precede the parousia, does not indicate a changed eschatological perspective on the author’s part but rather the urgent need to demolish the belief that the parousia could be present while this evil age is still so clearly in evidence.46

It would have been natural for whoever brought the news of the situation at Thessalonica to Paul (2 Thess. 3: 11) to stress the increased potential for disorder in the community. Such unruliness had already concerned Paul in Letter B (1 Thess. 5: 14); a second and more vigourous admonition (2 Thess. 3: 6, 11) would have been entirely appropriate.

This scenario is admittedly speculative, but it has the merit of dealing adequately with all the relevant aspects of Letter B and 2 Thessalonians. In weighing its value, its intrinsic plausibility must be contrasted with the utter improbability of the scenarios sketched to justify 2 Thessalonians as a pseudepigraphic construction.47 It is easy to ascribe motives to a post-Pauline Christian author, but impossible to explain how and why the newly created letter was accepted as Pauline.

We are now in a position to sum up. Paul wrote three letters to the Thessalonians. The first, Letter A, was written from Athens, some ten weeks or so after Paul had fled from Thessalonica, hence, in the spring of AD 50. Letter B was written next, but from Corinth. The interval between these two letters is difficult to calculate, because an unspecifiable length of time has to be allowed for Corinthian converts to visit Thessalonica and return. This could have happened during the summer of AD 50.48 How and when news of the misinterpretation of Letter B, which created the need for a third communication, 2 Thessalonians, reached Paul is impossible to determine, but nothing demands that a great interval separated them. 2 Thessalonians, therefore, could have been written in the late summer or early autumn of AD 50 or, at the latest, the following spring.

Thessalonica owes its name to Thessalonike, a half-sister of Alexander the Great.49 Her husband, Cassander, founded the city in 316 BC by amalgamating a number of villages on the best natural harbour in northern Greece at the head of the Thermaic Gulf.50 It is frequently mentioned in the war which concluded with the conquest of Macedonia by Rome in 167 BC; its shipyards were important.51 When Macedonia was made a Roman province in 146 BC, Thessalonica became the capital. Its economic prosperity was greatly enhanced in 130 BC when the Via Egnatia was constructed, linking it to Neapolis in the east and the Adriatic Sea on the west (see Fig. 7).52 Strabo called Thessalonica ‘the mother city of what is now Macedonia’ because it had the biggest population.53 A native son, Antipater, addressed it as ‘the mother of all Macedonia’.54

Thessalonica was not permitted to stand aloof from the confusion of the Roman civil wars. Cicero spent six miserable months in exile there (May-November 58 BC) but none of the eighteen letters he wrote in this period tell us anything about the city. From the spring of 49 BC to August 48 it became a second Rome.

For not only the consuls, before they had set sail, but Pompey also, under the authority he had as proconsul, had ordered them all [the senators] to accompany him to Thessalonica, on the ground that the capital was held by enemies and they themselves were the senate and would maintain the form of government wherever they should be. For this reason most of the senators and the knights joined them, some at once, and others later, and likewise all the cities that were not coerced by Caesar’s armed forces.

(Dio Cassius, History 41. 18. 4–5; cf. 41. 43. 1–4.; trans. Cary)

Julius Caesar put paid to such ambitions as effectively as his own were demolished by Brutus and Cassius. These latter in turn fell to Octavian and Antony. Thessalonica so admired Antony that its rulers created a new era in his honour. The degree of embarassment this caused after his defeat by Octavian at Actium in 31 BC is evident in the erasure of the dates from inscriptions.55 Octavian, however, held no grudge, and the honours accorded him by the city were reciprocated by an acknowledgement of Thessalonica’s status as a free city.56

The vitality of the population eventually would have repaired the damage of the civil wars, but Augustus speeded up the process by establishing Roman colonies ‘at Dyrrachium, Philippi and elsewhere’.57 This development could only have benefited Thessalonica, given its port at Neapolis and its position on the Via Egnatia. A brief report of Tacitus that in AD 15 ‘since Achaia and Macedonia protested against the heavy taxation it was decided [by Tiberius] to relieve them of their proconsular government for the time being and transfer them to the emperor’58 is significant on two counts. The fat pickings expected by the governors underlines the increasing prosperity of the province, but this is perhaps of less importance than the inference that the financial élite, which must have been concentrated in the capital, Thessalonica, had enough clout in Rome, not merely to have one or two rapacious governors disciplined, but to have the system changed. This meant intimate and continuous contact with Rome, in addition to access at the highest level. In AD 44 Claudius made Macedonia independent once again by detaching it from Moesia and restoring it to senatorial control.59

The special relationship between Thessalonica and Rome is graphically illustrated by the city’s acceptance of the divinity of Julius Caesar, which subsequently found expression in the establishment in Thessalonica of a temple of Caesar directed by a priest and agonothete of the emperor Augustus.60 Roman benefactors were already being honoured by a priesthood early in the first century BC. Sometime later the goddess Roma was associated with them; the benefactors were the channels through which her bounty reached the city.61 Inscriptions reveal a consistent hierarchy of cults; the priest of Augustus, the priest of ‘the gods’ (the tutelary deities of the city), and the priest of Roma.62 The pre-eminence of Roman-oriented cults is a clear indication that civic life was dominated by those whom the native inhabitants of the city considered outsiders. This is confirmed by the fact that official decrees of the city were sometimes enacted in conjunction with the association of Roman traders.63

Even though Romans exercised political and ideological control, they were only one component of the city’s élite. There was also a municipal cult of the Egyptian gods, whose functionaries created a dining club of some social pretensions under the patronage of Anubis.64 An inscription records a divine imperative to propagate the cult of these gods in the interior of the country.65 If Thessalonica had such contacts with Egypt, one can be sure that it entertained equally intimate relations with the other trading cities of the eastern Mediterranean, whose pantheons are well represented.66 Profit was the unifying factor in a merchant class whose membership was drawn from everywhere but the city in which they made their living. The local indigenous population found itself blocked by foreigners from access to the decision-making process, and cut off from the sources of real wealth, in which they participated as salaried employees or even more remotely as slaves.67

The letters indicate that the Thessalonian Christians were drawn from this latter group. The admonition ‘to work with your [own] hands’ (1 Thess. 4: 11) assumes that the community was recruited essentially, if not exclusively, from the working class.68 The hint that manual labour was the normal occupation is confirmed by 2 Thessalonians 3: 12, where those who have ceased to practice their trades are advised to return to working and earning a living. The same conclusion emerges from another line of argument based on the poverty of the Thessalonian church. The ‘extreme poverty’ of Macedonian believers (2 Cor. 8: 2) explains why, despite unusually intensive labour (1 Thess. 2: 9; 2 Thess. 3: 7–9),69 Paul needed to be subsidized more than once by the Philippians (Phil. 4: 16). In the letters there is not the slightest trace of the wealthy patrons—the householder Jason and certain prominent women—who dominate the scene in Acts 17: 1–10. It has also been pointed out that the injunction ‘If anyone does not want to work, let him/her not eat’ (2 Thess. 3: 10) is most at home in a situation where everyone in the community was expected to make a contribution to the common meal.70 In the absence of an individual capable of hosting the community (Rom. 16: 2, 23), the members had to entertain themselves. Thessalonian Christians met in tenements, not in villas.

Correspondingly, the workshop was the scene of Paul’s ministry in Thessalonica.71 It is not known who employed him,72 or whether the workshop was part of his patron’s residence, or how big the establishment was. It is clear, however, that there must have been a considerable demand for tents and other leather articles in a city which had so many travelling merchants. We should envisage a setting which provided Paul with both a stable base and a web of ready-made contacts focused on his patron, the clients, and his fellow-workers.73 All three groups had family and friends, and unless the patron was a very wealthy person, which does not seem probable for this type of business, there must have been continuous interchange on a variety of different levels, all of which Paul could put to use (‘working we proclaimed’, 1 Thess. 2: 9). Such a workshop would be in a busy street or market, another world which made demands upon Paul’s energies.

The average artisan had to work twelve hours a day seven days a week in order to barely make ends meet.74 How did Paul manage to make converts in this bustling preoccupied milieu? The only serious attempt to answer to this question is Jewett’s hypothesis that Paul’s preaching of Jesus filled a spiritual vacuum.75 Earlier scholars had noted the importance of the mystery cult of Cabirus at Thessalonica, its distinctive features, and its progressive development into an official religion, but Jewett is the first to exploit the consequences for the labouring class from which the first Christians were recruited.

The Cabirus legend tells of a young man, murdered by his two brothers, who was expected to return to aid the powerless and the city of Thessalonica.76 His symbol was the hammer, and his blessings were invoked for the successful accomplishment of manual labour. He was the god to whom the Greek working class looked for security, freedom, and fulfillment. For some unknown reason in the Augustan age Cabirus was taken up by the ruling élite and incorporated into the official cult. This left the artisans and workers of Thessalonica without a benefactor. They naturally assumed that he, like other gods, was more responsive to the appeals and gifts of the wealthy. The sense of alienation was intensified by the fact that the members of the ruling élite were perceived as outsiders. Not only did they deny to the indigenous population the democratic equality which Greeks felt to be their birthright, but they had monopolized the sources of profit, and now they had taken away the one traditional divine friend of the poor.

Given these circumstances, it is easy to see how attractive Paul’s preaching would be to the dispossessed; it reproduced the broad lines of a theology which they had thought lost.77 He proclaimed a murdered young man, who had in fact risen from the dead, and who, in consequence, had the power to confer all benefactions in the present. Moreover, he would assume all his followers into a very different world.

It is not difficult to surmise, as Jewett has emphasized,78 that the hint of a new ‘god’, who would radically transform the situation of the underprivileged, would have been perceived by the municipal authorities as subversive. Were the movement to take root and grow, it would threaten the fabric of society. However ridiculous the crucified Jesus of Nazareth might appear as a ‘god’ to sophisticated Romans or Greeks, the ruling class was politically astute enough to recognize the danger of an uncontrollable ‘god’ outside the structures of civic religion. He could serve as a rallying-point for a proletariat which by definition was unsatisfied. His message could be the magnifying glass to give inflammatory focus to frustrated ambitions. Under his inspiration, stirrings of unease could become revolutionary action.

Paul was used to being misunderstood and to being abused for it, and this was the type of persecution about which he warned his converts (1 Thess. 3: 4). He must have been as astounded as his converts when the authorities moved against them for very different reasons. He knew his message to be no threat to the security of the city. His converts, on the other hand, had assumed that in their new state they would be exempt from the violence that was endemic to their previous existence. Their reaction to persecution was not fear or cowardice but mental perturbation (1 Thess. 3: 3).79 Recognition of the potentially disastrous consequences of such disorientation, namely disappointment so profound as to lead to the abandonment of the faith, explains why Paul was so anxious about the steadfastness of the Thessalonians. If they felt that they had been deceived, all was lost.

We have seen above the exuberant relief expressed by Paul in Letter A after Timothy informed him that the Thessalonians, though bewildered, had remained faithful. We do not know whether Timothy’s report went beyond the single issue which had been the raison d’être of his mission to alert Paul to other features of church life at Thessalonica. If it did, the latter’s euphoria at the survival of the community effectively blocked assimilation of other details of their life. Only in Letter B do we find out what was really going on in the community, as Jewett has so brilliantly demonstrated. What does the way Paul handled the situation tell us about him at this stage of his career?

A. J. Malherbe has very astutely used texts from the philosophical tradition to bring to light the emotional state of the members of the nascent church at Thessalonica.80 Founders of philosophical sects were very explicit about what their recruits were going through. The commitment to a new vision of life brought in its train ‘social, as well as religious and intellectual dislocation, which in turn created confusion, bewilderment, dejection, and even despair in the converts.… This distress was increased by the break with the ancestral religion and mores, with family, friends, and associates, and by public criticism.’81 Malherbe also draws attention to the concern of a sect to define its specific identity and to the efforts made by the group to assimilate new members. His detection of similar features in 1 Thessalonians leads him to the conclusion that ‘Paul consciously used the conventions of his day in attempting to shape a community with its own identity, and he did so with considerable originality’.82

Given the quality of Paul’s secular education, it is not at all impossible that he should have been acquainted with the philosophical tradition, but I find it difficult to concede that he deliberately adopted its techniques. Even if he knew of them, he must have considered them inappropriate, because the community he desired to create was different from all other groupings in that an indispensable feature was mutual love (1 Thess. 4: 9).83 Is it not much more probable that Paul drew on his own experience? He needed no one to tell him what the Thessalonians were going through. He had been converted twice, the first time to Pharisaism, and the second time to Christianity.

Thus when Paul speaks of the Thessalonians as ‘having received the word in much affliction and joy inspired by the Holy Spirit’ (1 Thess. 1: 6), we catch a glimpse of his own initial ambivalence on two occasions. The profound satisfaction of doing what he believed to be God’s will was mixed with a gnawing sense of loss. The past still bound him emotionally, while the future had not yet established its claim. What got him through this stressful period was the support of the community he had joined, Pharisaic in Jerusalem,84 and Christian in Damascus. This is the obvious source of the kinship language which Malherbe has highlighted as one of the features of 1 Thessalonians.85 As both ‘father’ (2: 11) and ‘nurse’ (2: 7), Paul relates to his converts as ‘children’, whose bonding is evoked by the unusually frequent use of ‘brethren’ (eighteen times). He tries to create for them the calm rooted in a sense of security, which he had himself experienced.

Role models had been an important factor in promoting Paul’s own stability. The conviction that led him to a new life had nothing to do with rational evidence. It was a leap of faith rooted in an unknowable impulse. Yet he would not have been human had he not felt the need for some justification. This he found in those whose lives exhibited, not only the fruits of the effort he was making (and perhaps considered inadequate), but the pattern of behaviour appropriate to the new mode of existence he had chosen. It was because he knew the importance of the satisfaction of his own need to see the gospel vindicated by comportment, in other words to see grace at work here and now, that he recognized his responsibility to be a model to the Thessalonians (1 Thess. 1: 6; 2: 9; 2 Thess. 3: 7, 9).86

Malherbe is certainly correct that this is the fundamental perspective in which Paul’s presentation of his ministry in I Thessalonians 2: 1–12 must be read, but he is unrealistic in divorcing it entirely from the situation at Thessalonica.87 It would be totally out of character for Paul to waste time depicting himself to believers as the ideal philosopher (cf. 1 Cor. 1: 19–20). Were he convinced that his example was being followed, why should he justify in detail his conduct when among the Thessalonians?

On what ground was Paul attacked? One cannot simply assume that each statement he makes is the refutation of a specific charge. That would imply a condemnation of the Apostle so thorough and radical that a completely different and much more vigourous response along the lines of 2 Corinthians 10–13 would be expected. A narrowly focused hypothesis is provided by Jewett who, following the lead of Lütgert and Schmithals, argues that Paul was reacting to an accusation that he had failed to display the ecstatic behaviour which would mark him out as a true ‘spiritual’.88 This view, however has no foundation in the text.89 Others have suggested that Paul was criticized for having decamped when the persecution began, leaving the Thessalonians to face the music alone. Again this is unfounded. Not only does Paul make no effort to justify his departure, which would be the only adequate response to such an accusation, but any such resentment on the part of the Thessalonians is excluded both by Letter A (1 Thess. 3: 6) and by Letter B (1 Thess. 1: 9) which note the respect in which Paul is held at Thessalonica.

The tension between the sweeping defence and the passionless tone suggests that Paul had become aware that he was the object of criticism, but knew none of the details. Only this explains his concern to refute all possible accusations without giving weight to any one in particular. His insistence in response to what must have been a hint rather than a report betrays a sensitivity to criticism, which is rather curious in a man of 50 who has been an active missionary for over ten years. This may have been a personality trait, but it was also the other side of his identification with his message. If he exemplified the gospel (2 Cor. 4: 10–11), then any attack on him was an affront to the word of God, which justified—necessitated?—a response.

The most probable source of criticism of Paul on the part of the Thessalonians is associated with his teaching on the eschaton. Their reading of Letter B (see above) is incomprehensible, unless they were convinced that they had been taught a realized eschatology. A predisposition to millenarianism is not an adequate explanation for their systematic transposition of all Paul’s future statements into present ones. They were hard-headed working people with little time for idealism, and a very limited capacity for self-deception. No doubt they heard what they wanted to hear, but for them to have continued listening to Paul, there must have been some relation between his teaching and their desires. For their tinder to have caught flame, he must have proposed fire, not water. There is, of course, the possibility that they misunderstood the Apostle. Even in that case it is most probable, as we shall see in other letters, that the seeds of such misunderstanding were sown by Paul himself. He tended to assume that his audience would know what he meant, no matter what he actually said, and his impetuous temperament often led him to overstatement and the use of ambiguous language.

The possibility of such misinterpretation can be illustrated by the traditional fragment which Paul cites in 1 Thessalonians 1: 9b–10, and which is commonly accepted as reflecting the basic tenor of his preaching. The creed is composed of two strophes, each containing three lines:

[We] turned to God from idols

to serve the living and true God

and to wait for his Son from heaven

Whom he raised from the dead

Jesus who delivers us

from the wrath to come.90

At first reading the meaning appears unambiguous, but a little reflection reveals that a simple shift of emphasis can change the interpretation radically. To put the stress on ‘to wait for his Son from heaven’ yields a future eschatology, but to highlight ‘Jesus who delivers us’ leads to a realized eschatology. One could even argue, on the grounds that the second strophe is designed to bring out the meaning of the first, that the latter interpretation is the dominant one. The waiting must be over, because Jesus is here and now delivering us; the coming wrath has been side-tracked. Thus even if Paul contented himself with reciting traditional doctrine—it is much more probable that he enthusiastically embroidered it—the Thessalonians could have heard him proclaiming a realized eschatology, intensified by his own fervour.

Whether Paul was in fact preaching a realized eschatology, as C. L. Mearns maintains,91 or whether he was merely thought to be so doing, developments at Thessalonica forced him to recognize the dangers of such a world-view when applied literally to daily life. The death of some members to whom a glorious assumption had been promised created intolerable problems for those left behind (1 Thess. 4: 13); it was something that should not have happened.92 Others, there is no indication of how many, exhibited a typical millenarian disregard for the demands of normal living, perhaps indulgence in sexual excesses, certainly the cessation of productive labour (1 Thess. 4: 11; 2 Thess. 3: 6–12).93

Charity demanded that Paul provide an answer for the bereaved, and his concern for the witness value of the community (1 Thess. 1: 6–8; 4: 12) made it imperative for him to exclude practices which would bring the church at Thessalonica into disrepute. Even if he had previously understood the creed (1 Thess. 1: 9b–10) as implying a realized eschatology, the need to move the gaze of the Thessalonians from the present to the future forced him to recognize that the creed does not necessarily proclaim a realized eschatology. The function of the second strophe could be merely to identify the Son whose advent is expected. He is none other than the Jesus who is now at work in the community through his Spirit (1 Thess. 1: 5–6; 4: 8; 5: 19). Be that as it may, Letter B contains a series of allusions to a future Parousia (1 Thess. 1: 10; 5: 2, 23), at which, Paul assures his readers, the beloved dead will not be left behind abandoned but, once raised from the dead, will be assumed with the living (1 Thess. 4: 13–18).

It was perhaps inevitable that the shift from a realized to a futurist eschatology should be accompanied by the conviction that the Parousia would take place within the life-span of the present generation (1 Thess. 4: 15, 17). This could be read as the implication of the creed’s choice of ‘to wait’. Those who said this creed would be alive when the waiting ended. On the subjective level, this belief facilitated Paul’s internalization of the new (or refined) perspective imposed on him by circumstances. As far as the Thessalonians were concerned, he hoped that it would minimalize the disconcerting dislocation caused by the substitution of a futurist for a realized eschatology. Paul, however, had failed to recognize the extent to which the Thessalonians had become imbued with the realized eschatology, which they believed to be his message. Their reaction was to move the proximate future, on which the Apostle now wanted to fix their gaze, back into the present (2 Thess. 2: 2). Thus another letter—2 Thess.—became necessary, in which Paul is forced to spell out the signs which will precede the in-breaking of the eschaton (2 Thess. 2: 3–12). Contrary to what he said in 1 Thessalonians 5: 2–3, the Day of the Lord will not come suddenly or quietly; it will be prefaced by major social upheavals.94

The doubt as to whether Paul actually preached a realized eschatology at Thessalonica, or was mistakenly assumed to have done so, is not resolved by the fact that he instructed converts in ethical behaviour during his initial visit (1 Thess. 1: 11–12; 4: 1, 6, 11; 2 Thess. 3: 10). Moral teaching was not an afterthought dictated by the delay of the Parousia. Even at the stage when his eschatological expectation was most intense, Paul’s perspective was radically apostolic. No matter how limited the time remaining, his mission was to convert the Gentile world. From his Jewish background he learnt that the word of God differs from all others in that it is intrinsically effective; it is laden with a power that transforms proclamation into performance.95 If the gospel really was the word of God, then it could not be ineffective. This insight was reinforced by his own experience, which taught him that the one essential apologetic argument was the demonstration of the power of the Spirit in the lives of the ministers of the gospel. They did not convince by carefully crafted persuasive arguments (1 Cor. 2: 4–5), but by revealing the effectiveness in their personalities of the word they proclaimed (1 Thess. 1: 5; cf. 1 Cor. 9: 2; 2 Cor. 3: 2).

An important factor in the imitation which Paul expected of his converts (1 Thess. 1: 6) was to be the prolongation of his apostolic mission. The Thessalonians fulfilled their duty as Christians to extend the range of the gospel (1 Thess. 4: 12) by being ‘an example’ (1 Thess. 1: 7); the existential proclamation of their lives manifested the power of the word at work within them (1 Thess. 2: 13; 2 Thess. 1: 4, 11).

While such teaching is beautiful and impressive, it is too vague to be practical. Without some specification it would be ignored. While at Thessalonica Paul had to indicate at least the broad lines of the type of behaviour he considered conducive to the diffusion of the gospel. In Letter A Paul presumes that the Thessalonians recall these directives (1 Thess. 4: 2). He is less sanguine in his next letter, and the close parallels between 1 Thessalonians 1: 11–12 and 4: 2 strongly suggest that 1 Thessalonians 4: 3–7 exemplifies the type of oral instruction he considered appropriate.

The limits of the section are clearly defined by an inclusion: ‘this is the will of God your sanctification’ (4: 3) is echoed by ‘God has called us in sanctification’ (4: 7). Best and Bruce reflect the opinion of most commentators by entitling 1 Thess. 4: 3–7(8) ‘Sex’ and ‘On Sexual Purity’, respectively. Neither title, however, accurately reflects Paul’s intention which is to draw attention to the difference between the life-style of believers and that of non-believers. The contrast is made explicit in the first and last verses.

The life-style of believers is qualified as ‘sanctification’ (vv. 3, 7), which in the first place does not denote personal sanctity but rather having been ‘set apart’ by God, and thereby ‘dedicated’ to God. Christians are ‘saints in virtue of a divine call’ (Rom. 1: 7; 1 Cor. 1: 2; cf. 2 Cor. 1: 1; Phil. 1: 1; Col. 1: 20); the complete absence of ‘saint’ in Galatians underlines that in Paul’s lexicon it is anything but a banal formula.

The alternative to ‘sanctification’ is described as porneia (v. 3) and akatharsia (v. 7). The latter means ‘uncleanness’ and is the antithesis of ‘sanctification’ used in the cultic sense just defined. Thus for a Jew it functioned as the definition of a pagan life-style.96 Rigaux’s claim that in Paul it always has a sexual connotation97 is excluded both by 1 Thessalonians 2: 398 and by the reference to the children of Corinthian parents at Corinth; their unbaptized state should make them ‘unclean’ but in fact they are ‘holy’ (1 Cor. 7: 14).99 Akatharsia, of course, can be used of sexual immorality. It is associated with pomeia ‘unchastity’ and aselgeia ‘licentiousness’ as works of the flesh in Galatians 5: 19 (cf. 2 Cor. 12: 21), and with epithymia ‘desire’ in Romans 1: 24. In both of these contexts, however, Paul is describing unredeemed humanity, and in a way which merely reflects the standard Jewish association of pagan cults and sexual debauchery (Hos. 6: 10; Jer. 3: 2, 9; 2 Kgs. 9: 22), which is made explicit here by ‘not in the passion of desire like the pagans who know not God’ (v. 5). It is in this same context that the contrast of pomeia with ‘sanctification’ is best understood; its connotation here is not specifically sexual (i.e. ‘fornication’) but symbolic, and in this sense is best rendered by ‘immorality’ (RSV).

That Paul is not thinking in terms of particular sexual problems at Thessalonica is confirmed by the admonition ‘that each of you learn to acquire his own skeuos’ (v. 4). Skeuos is literally a ‘vessel’ (2 Cor. 4: 7), and the two standard interpretations here understand it as meaning ‘body’ (NRSV) and ‘wife’ (RSV). The basic argument which has prompted the adoption of ‘wife’ is well stated by Best, ‘No one can be said to “gain his body”.’100 This, however, is to forget that, for Paul, unbelievers are not their own masters; they are manipulated by social and economic forces to the point where they are ‘under the power of Sin’ (Rom. 3: 9) or ‘enslaved to Sin’ (Rom. 6: 17).101 Thus liberation from Sin meant that one had to learn self-mastery in a much more profound and wide-reaching sense than physical self-control.102 The sexual language (‘not in the passion of desire’, v. 5) in which the antithesis is expressed should not be permitted to blur the real contrast between the chosen commitment of ‘dedication to God’ and the servitude of the unbeliever, who is the victim of socially conditioned desires, ‘Do not let Sin reign in your bodies to obey its desires’ (Rom. 6: 12).

The mention of ‘brother’ in verse 6 recalls the specific identity of the group to which the believers belong. The attitude that one should have is described negatively by two verbs ‘(not) to go beyond’ and ‘(not) to take too much’. In essence this is a warning against ‘covetousness, greed’, which caused the Fall (Rom. 7: 7), and which remains the dominant characteristic of fallen humanity (Num. 11: 34; 1 Cor. 10: 6). For most commentators the nature of the injury is limited to sexual matters (i.e. adultery) by ‘in the matter’, because the demonstrative article must refer to what has been mentioned previously. As we have seen, however, the sexual dimension of the preceding verses is merely a symbolic representation of the disordered and disorderly life-style of pagan non-believers.

The function of 1 Thessalonians 4: 8 (‘whoever disregards this, disregards not man but God who gives his Holy Spirit to you’) is to underline the fundamental importance of the distinction between the two modes of being. The gift of the Spirit as the source of sanctification is the effective implementation of the ‘call’ which articulates the ‘will of God’. It enables discernment and empowers the choice of good. The directives in 1 Thessalonians 4: 3–7 are so generic that they set a direction without imposing specific obligations. They do no more than alert the Thessalonians to the fact that they must discover a lifestyle appropriate to their new being in Christ. The function of the directives is educative. Designed to orient those who have moved from an egocentric form of existence to an other-directed mode of being, they are the counsels of a wise father to his children (1 Thess. 2: 11–12).

The assumption underlying Letter A, namely, that the Thessalonians had grasped what Paul wanted to convey, could no longer be maintained when he wrote Letter B. He found himself forced to offer more explicit guidance. The way he handled this aspect of his problems with the Thessalonians reveals him to be much more consistent and clear-minded in the domain of Christian living than in that of eschatological speculation. The directives he gives are a mixture of advice and precepts. The latter, however, are entirely generic (1 Thess. 5: 13b–22)—they concern values rather than structures—whereas the former are very detailed (1 Thess. 4: 10b–12; 5: 12–13a). Thus in Letter B Paul does not impose or prohibit any specific act. More significantly his list of commands embodies the crucial ‘test everything’ (5: 21a), which throws back to the Thessalonians the responsibility for their moral decisions. In the last analysis it is their judgement that counts. The implication that the Thessalonians themselves are responsible for the running of their own community is also significant. Paul did not consider it his role to tell them what to do.

This high-minded approach to morality came under severe pressure, when it became clear that certain members of the community continued to lead disorderly lives. Ataktos ‘disorderly’ is found once in Letter B (1 Thess. 5: 14); its cognates appear three times in 2 Thessalonians (3: 6, 7, 11). Correspondingly, the single instance of parangellô in Letter B (1 Thess. 4: 11) jumps to four in 2 Thessalonians (3: 4, 6, 10, 12). The meaning of this verb ranges from ‘to give advice, to notify, to inform’ at one end of the scale to ‘to order, to command’ at the other end.103 Which did Paul intend?

Despite a number of commentators, ‘to command’ is not required in 2 Thessalonians 3: 4 and 6; ‘to instruct’ is perfectly adequate.104 Paul is formally indicating the line of action he wants the community to adopt, namely to ostracize the unruly, thereby making it quite clear to outsiders that true Christians do not act in ways condemned. Such restraint, however, breaks down at the very end of the letter. The correlation of the imperatival infinitive ‘do not mix with’ and ‘if anyone does not obey’ in 2 Thessalonians 3: 14 unambiguously indicates that Paul expects them to do precisely what he says. To mandate a moral decision concerning the effective exclusion of a community member is a definite deviation from Paul’s practice as revealed in the two previous letters.105 His justification for the exception can only have been the hope that the punishment will effect the reformation of the erring brother (2 Thess. 3: 15). A more mature and sophisticated Paul will achieve the same result without compromising his principles in 1 Corinthians 5: 1–5, but by then he will have worked out most if not all of the implications of the incident at Antioch (Gal.2: 11–14).106

It is highly indicative of Paul’s understanding of the nature of his authority, and of how it should be exercised, that he does not install a representative at Thessalonica to report back to him, and to ensure that his wishes are carried out. This signals his recognition of the autonomy of the local church. It is responsible for itself. In consequence, it must evolve its own leadership. The most that Paul can do is to hint at what qualities he considers necessary in such leaders. The Thessalonians should ‘acknowledge those who labour among you, taking the lead in caring for you in the Lord and admonishing you’ (1 Thess. 5: 12).107 Such total dedication to the good of others can only be the fruit of love. Hence the only appropriate response is love (1 Thess. 5: 13). The leaders whom Paul hopes will emerge are not identified by social position or special skills, and the relationship of others to them is not one of obedience or deference. In this we catch a further hint of Paul’s awareness that the Christian church is radically different in nature from any secular grouping. His perception of its true identity will grow. At this stage in his career all that comes across is that it is a community of love which radiates love (1 Thess. 3: 12; 4: 9–10).

The eschatological issue at Thessalonica brought to light traits of Paul’s character which will emerge with some consistency in other situations. He was not very good at working out what was going on in other peoples’ minds. Certainly he never developed much insight into the mentality of the Thessalonians, even though the unusual problem of cessation of work had already manifested itself during his visit (1 Thess. 4: 11; 2 Thess. 3: 10). Presumably his delight at their response to his preaching—for which he would certainly have given the credit to divine power—made it impossible for him to grasp how exactly he was coming across. Inevitably he was mystified at the practical outcome of his words, and deeply hurt at criticism of his changeability, when he attempted to correct what he perceived as egregious misinterpretations of his teaching. His first attempt to rectify the realized eschatology of the Thessalonians was not successful. The alternative futurist version was not presented with sufficient vigour and clarity.

The hesitancy may be due to the belated recognition of the extent of his own responsibility. He found himself in the unhappy position of attempting to controvert well-received ideas, which the Thessalonians believed he accepted when he lived among them. In order to avoid the impression that he was making a complete about-face, he merely insinuated the new perspective by parenthetical allusions to the Parousia (1 Thess. 1: 10; 3: 13; 5: 2, 23), while at the same time giving the Thessalonians latitude to persevere in their error by phrases such as ‘But as to the times and seasons, believers, you have no need to have anything written to you’ (1 Thess. 5: 1).

Paul’s naïveté in interpersonal relations is highlighted by his shock at the failure of the Thessalonians to respond to what he saw as his gentle but firm and unambiguous invitation in Letter B. He had learnt a lesson, however, and his voice in 2 Thessalonians is clearer and much more forceful. But in order to get out of a corner he had to adopt an apocalyptic scenario (2 Thess. 2: 1–12) as an ad hominem argument. We do not know with what degree of conviction he accepted the scenario, whose meaning may have been just as obscure to the Thessalonians as it is to contemporary exegetes,108 but he never used it again.

The assurance of his moral teaching, on the contrary, is noteworthy and betrays a clear vision of the nature of the Christian community. Evidently he was much more concerned with what the community did than what it thought, and had worked out a strategy in advance. From the beginning he realized that if the Thessalonian church was to have the sort of witness value that would reinforce and prolong his mission, its members would have to exhibit an attractive, freely chosen life-style. This intuitive insight would soon be strengthened by the conviction that to impose binding precepts would be to recreate the Mosaic law for believers. To acquire that conviction, however, he had to live through a crucial meeting in Jerusalem, and an agonizing conflict at Antioch.