WHEN Paul finished writing 1 Corinthians and dispatched it with the returning delegation, he evidently considered that he had done all that was necessary for the moment. The care he had expended on the letter, he felt, justified a high degree of optimism as to its successful impact. A leisurely swing through the churches of Macedonia which, for all their problems, were as angels compared with the Corinthians, would refresh his spirit. It would be sufficient to reach Corinth at the end of the summer (of AD 54), and he could pass the winter there, if a long stay was indicated (1 Cor. 16: 5–7). These plans were completely disrupted by the need to make an unplanned visit to Corinth.

Whether or not Paul made a visit to Corinth between writing 1 Corinthians and 2 Corinthians—the so-called Intermediate Visit—depends on the interpretation of two difficult texts in 2 Corinthians.1 The first is 2 Corinthians 12: 14 which can be translated in two ways: (a) ‘Behold! This is the third time I am making preparations to come to you’ and (b) ‘Behold! I am ready to come to you for the third time.’ The former means that Paul had planned to come to Corinth on several occasions but never succeed in accomplishing his purpose. The latter indicates that Paul had visited Corinth twice already. The same ambivalence plagues 2 Corinthians 13: ia, which can be rendered: (a) ‘this third time I am coming to you’ (in opposition to two previous times when he tried but could not make it), or (b) ‘this is the third time I am coming to you.’

Everything, therefore, hinges on the meaning of 13: 2, which may be translated very literally as ‘I have said previously and I say beforehand, as being present the second time and being absent now, to those having sinned previously and to all the others that if I come again I will not spare.’ The complexity of the sentence is due to the fact that Paul is thinking in two different time frames. Once this is recognized, it is easy to separate and link the elements which go together:2

(a) ‘I have said previously’ = ‘being present the second time’

(b) ‘I say beforehand’ = ‘being absent now’

The prefix pro- in the verbs does not have the same point of reference in each case. In (a) it looks back to a time before the present, whereas in (b) it looks forward to a moment in the future. The latter—in the perspective of (a)—can only be a third visit. The ambiguity of 13: 1 is thereby removed; the only translation possible is: ‘this is the third time I am coming to you’, which in turn determines the sense of 12: 14. Paul’s point is to repeat something—‘If I come again I will not spare’3—which he once said in the presence of the Corinthians on the occasion of a second visit, and which he now repeats in anticipation of a third visit. The two statutory warnings having been given, he will be free to act as soon as he arrives.4 The hint that the second visit was not a pleasant one is unmistakable. What happened?

We have no direct information as to what brought Paul to Corinth not long after he wrote 1 Corinthians. The data available, however, permit only one hypothesis. Timothy carried back news which galvanized Paul into action.5 1 Corinthians inadvertently betrays the latter’s anxiety regarding how Timothy would be received at Corinth (4: 14–21). Paul’s fear is not expressed in so many words, but the sudden shift in tone from the serene introduction of Timothy (4: 17) to the heated outburst, ‘Some are arrogant, as though I were not coming to you’ (4: 18), reveals Paul’s emotional response to his sudden vivid image of what Timothy might be going through.

The possibility continued to worry him, and he made his concern explicit at the end of the letter. He did not want Timothy to be frightened or despised (1 Cor. 16: 10–11). Paul suspected that the spirit-people, who looked down on him for his lack of religious sophistication, would tend to adopt a similarly dismissive attitude towards his delegate. And Paul did not know how much support Timothy would find elsewhere in the community. Fear is often the concomitant of isolation. The agitated affection of Paul for his younger colleague culminated in a veiled threat, ‘I am awaiting him with the brethren.’ Commentators have made it clear that ‘the brethren’ cannot be either the three Corinthians mentioned in 16: 15 or other Corinthians supposed to come with Timothy. They must then be the members of the church at Ephesus. Timothy’s fate would be a matter for the whole community—with possible repercussions for the business relations between the two churches.

The simplest explanation of Paul’s surprise visit to Corinth is that it was motivated by Timothy’s report.

Much of what happened when Paul got to Corinth is shrouded in obscurity. He knew what had occurred and so did his readers. He did not have to rehearse the details. We have to try to work backwards from what is incidentally revealed of the aftermath in 2 Corinthians 2: 1–11 and 7: 6–16. The available clues must first be tabulated, and then assessed individually, if the reconstruction is to have any claim to objectivity.6 The established facts concern both the offence and the response of the community: (1) a single Christian (2: 6; 7: 12) made a serious attack (2: 1, 3, 4) on Paul personally (2: 5, 10); (2) the members of the church did not manifest the personal loyalty and enthusiasm that Paul had expected (7: 12). They were sufficiently at fault to experience the need for repentance (7: 9). Yet they managed to convince Titus of their innocence in the matter (7: 11).

Barrett eases the palpable tension between the last two elements (7: 9 and 11) by suggesting that the offender, though a Christian, was only a visitor and not a member of the Corinthian community.7 This inference is refused by Wolff on the grounds that the church could have disciplined only one of its own members (2: 6–7).8 However, the most severe penalty that the community could inflict was to withdraw from all contact with an individual (cf. 1 Cor. 5: 11), and it was perfectly feasible for it to refuse the hospitality which the visitor had hitherto enjoyed. Hence, unless we are prepared to assume that Paul was telling a lie in order to exculpate the Corinthians (7: 11), we must conclude that the incident was provoked by an intruder.9

Why would an intruder challenge Paul’s authority? This question is an invitation to unbridled speculation, and hypotheses have proliferated. It is much more profitable to ask: how could the intruder act in such a way that Paul would feel himself profoundly insulted and personally injured, but that the community would consider the issue to be none of its business? The answer, which builds on what we have already discovered, and which reveals the seeds of subsequent developments, is that the visitor was a spokesman of the delegation which Antioch had sent to exercise its rights over the churches that Paul had founded in its name.10

While still a prisoner in Ephesus, Paul had become aware of the ambitions of the Judaizers to follow him into Europe, and wrote to Philippi to alert the church there of its danger (Phil. 3: 2–4: 1).11 Presumably, the reason for his planned visit to Macedonia (1 Cor. 16: 5) was to check whether the situation he feared had in fact developed. In these circumstances, the worst possible news that Timothy could have brought back to Paul was that the Judaizers were far ahead of him, and had already penetrated Corinth. Paul’s sense of shock and outrage would have been exacerbated by the realization that they must have passed through Macedonia to get there. He would not have been caught so unawares had they passed through Ephesus. Philippi and Thessalonica, in consequence, were also at risk.

What was Paul to do? The first option was to continue with his original project, to go first to Macedonia and then to Corinth. This plan had little to recommend it. To follow the Judaizers around put him at a psychological disadvantage. They were making the running, and he was only playing catch-up. Moreover, Paul’s relations with Thessalonica and Philippi were good. The problems of these churches with which he had to deal had not affected the affection in which he was held. At Corinth, on the contrary, he was not universally admired. The spirit-people, at least, were against him. And on reflection in this moment of crisis he may have realized that the strategy he had adopted in 1 Corinthians would not have made them any friendlier.

Recognition of this fact was decisive. Just because the Judaizers were opposed to Paul, they were more likely to get a favourable reception at Corinth than in Macedonia. Hence, it was imperative for Paul to go in person to Corinth. But something had to be done about Macedonia. Even though Philippi was aware of Paul’s views on Judaizers (Phil. 3: 2 to 4: 1), a personal visit could only be beneficial. Even without the evidence of Acts 19: 22, it would have been natural to assume that the responsibility was entrusted to Paul’s most valued co-operator, Timothy, particularly since his visit to Philippi had already been announced (Phil. 2: 19).

Timothy’s heart must have been heavy as he headed north with Erastus (Acts 19: 22) to take ship from Troas. The impact of his news from Corinth on Paul had dismayed him, and he did not know what hostility he might face among the believers in Macedonia, where the Judaizers had had the time to establish a firm base. The burden he carried, however, could not be compared to that borne by Paul. As the ship swooped over the waves en route to Cenchreae, the eastern port of Corinth, it is easy to envisage the depressed state in which his imagination created one scenario worse than the other, while he mulled over different possible strategies. If he lost Corinth, his enemies would have completed their encirclement, and Ephesus at the centre could not long survive. The whole future of the Gentile church was at stake.

The confrontation at Corinth with the leader of the Judaizers was undoubtedly dramatic.12 The line taken by the latter must have been very similar to the one he took in Galatia.13 Paul, he asserted, was a dishonest representative of the church which had sent him out to proclaim the common faith. A traitor to his commission, Paul preached his own ideas, not the common gospel. The dismissive tone in which the slanders were pronounced added insult to injury. Paul leaves us in no doubt that he had been deeply humiliated, and his authority challenged in the most radical way possible.

Yet what perturbed him most was the attitude of the Corinthians. Their failure to come to his support cut him to the quick. From the perspective of an outsider this is not as disconcerting as Paul found it. The attitude of the church of Antioch was irrelevant as far as the Corinthians were concerned. They were confident of their own identity, and they had absorbed Paul’s teaching on the autonomy of the local community. The idea of a claim based on a genetic connection with another church would have seemed rather unrealistic to them. The success of Jerusalem in imposing its ethos on Antioch was no concern of theirs. It might matter to Paul, but in that case he could fight it out with the intruder on a purely personal level.14

Naturally Paul did not see the episode in this light. Not only was there the matter of his wounded vanity—those whom he had engendered through the gospel (1 Cor. 4: 15) should have preferred him above all others—but the ‘neutrality’ of the Corinthians induced the suspicion that they were prepared to listen to the Judaizers. In fact the Corinthians might have replied, when Paul asked them to reject the intruder, that no one should be condemned without a fair hearing. This, of course, was precisely what Paul wanted to avoid. The report from Galatia had revealed to him the seductive character of the message of the Judaizers. One might reasonably suspect that the spirit-people were behind the refusal to let Paul lord it over their faith (2 Cor. 1: 23); the wounds caused by his treatment of them in 1 Corinthians were still open and bleeding.

The obstinacy of the Corinthians put Paul on the horns of a dilemma. On the one hand, he wanted to stay in Corinth to counter the arguments of the Judaizers, but on the other hand he believed himself to be necessary in Macedonia, where they were also active. He could not stay indefinitely in Corinth, and perhaps he recognized that his presence was only exacerbating the situation. The beneficial effects on everyone of a breathing space may have been a factor in his decision to leave. Where did he go?

A number of commentators assume that Paul returned directly to Ephesus, on the grounds that 2 Corinthians 1: 15 plans a voyage with the following components: to visit Corinth first, from there to go to Macedonia and to return to Corinth, whence he would leave for Judaea.15 In writing thus, however, Paul was attempting to justify not one but two changes of plan. The first he had announced to the Corinthians in 1 Corinthians 16: 5–6; he would come to Corinth via Macedonia. In fact, the circumstances discussed above forced him to go to Corinth first. It is this revised plan that he tries to present in the most attractive way possible by implying that he had changed his mind because of the unique importance of Corinth in his eyes; it would get two visits instead of one (2 Cor. 1: 15). At the time of writing he had in fact visited Corinth—the so-called intermediate visit—but subsequently changed the travel plans he had announced there, namely, to go to Macedonia and then return to Corinth (2 Cor. 2: 1). He went straight from Macedonia to Ephesus (2 Cor. 2: 12–13).16

This interpretation is reinforced by the inherent probabilities of the situation. If anything, Paul’s reason for going to Macedonia (1 Cor. 16: 5–6) had been reinforced by his painful experience at Corinth. Since he himself had found it impossible to control the Judaizers, what chance would the less authoritative Timothy and Erastus have had? Even without 2 Corinthians 1: 15, we would be obliged to deduce that, from Corinth, Paul went to Macedonia in order to check on the situation there.

It is most improbable that Paul sailed north from Corinth. Not only was the voyage long and dangerous, but the Etesian winds began to blow strongly from the northern quadrant in mid-June and continued for three months, making northward navigation difficult if not impossible.17 The overland route from Corinth to Thessalonica is 580 km. (363 miles).18 At an average of 32 km. (20 miles) per day the journey would have taken roughly three weeks. Whether Paul would have been able to maintain this average is another matter. He had to cross the great double plain of Thessaly, which in summer is one of the hottest places in Europe.19 The mountains that ring it still contain the bears, wolves and wild boar, which are mentioned by Apuleius.20 These, he feared, were awaiting him in the passes to the north, and apprehension must have intensified the exhaustion of the trek across the sun-seared plain.

There can be little doubt that Paul’s physical state was an accurate reflection of his dispirited frame of mind as he walked slowly into Thessalonica sometime around mid-July AD 54. The trouble he anticipated, however, did not materialize. There is no hint that he had to confront the Judaizers either there or in Philippi. On the contrary, the commitment of the Macedonians to his cherished project of the collection for the poor of Jerusalem reveals them to have been entirely on his side (2 Cor. 8: 1–4). The short shrift given to the Judaizers by the Macedonians explains how they reached Corinth so quickly. The contrast between their fidelity and the mocking neutrality of the Corinthians intensified the bitterness that Paul felt towards the latter.

Perhaps under the influence of Timothy, who is likely to have stayed on in Macedonia, Paul had the good sense to realize that it would be unproductive to return to Corinth with bile seething within him (2 Cor. 2: 1). It could only lead to another explosion and even greater damage. Hence, he decided to change his plans, even though this would give the Corinthians another stick with which to beat him. He found a ship sailing from Neapolis to Troas. From there it was a 350 km. (210 mile) walk to Ephesus. He could have been home in early August.

Even though he had decided not to return to Corinth, Paul felt that he owed it to himself and to the Corinthians to explain how he felt about what had happened during his visit. It was not an easy letter to write. ‘I wrote you out of much distress and anguish of heart and with many tears’ (2 Cor. 2: 4). The letter has been lost and cannot be reconstructed in detail.21

From the way Paul speaks of the reception of the letter in 2 Corinthians 2 and 7, it is clear that the letter was in no way similar to the one he had written to the Galatians. He did not deal with the arguments of the Judaizers, but focused exclusively on his own relations with the Corinthians (2 Cor. 2: 9; 7: 12). His strategy was to win their sympathy by revealing their treachery through the description of his hurt. The letter was designed to tug at the heartstrings, while at the same time administering a severe shock. The missive had to be strong enough to shake the Corinthians, but not so brutal as to alienate them. Effective reproof had to be blended with the assurance of his affection. The delicacy of the decisions made the writing an agonizing business. Even after it had been dispatched, Paul fretted about the impact of the letter. It might do more harm than good. It might have stood a better chance of achieving his goal, had he said this rather than that. The uncertainty weighed upon him terribly.

The letter was entrusted to Titus (2 Cor. 2: 13; 7: 6). It would not have been tactful to send Timothy, who at the least had been the occasion of the blow-up between Paul and the Corinthians. No matter what other assistants may have been available, Titus had a special qualification. He had been with Paul at the Jerusalem Conference (Gal. 2: 1–3). What this meant, is well formulated by Barrett,

There is thus the strong probability that Titus emerged from the Jerusalem meeting the uncircumcised Gentile he had always been, and that he would retain from this gathering a keen awareness of the peril of legalistic Judaism and of the activities of false brothers; also he would be aware of the quite different (even if not wholly satisfactory) attitude of the main Jerusalem apostles.22

Titus, in other words, made an admirable foil to the Painful Letter, in which Paul had poured out his anguished deception. He was in a position to report authoritatively on the agreement between Paul and the Mother Church and thereby to refute any claims, or highlight any distortions, of the Judaizers.23

In 2 Corinthians 2: 13–14 Paul gives the impression that his departure from Ephesus was motivated by his affection for the Corinthians and his desire to have news of them.24 In order to encounter Titus as soon as possible he moved north to Troas and then aborted a fruitful ministry there in order to cross over to Macedonia.

The first question raised by this scenario is: why did Paul settle down to minister in Troas? If he failed to find Titus there, would his concern not have driven him to sail to Neapolis, and then backtrack along the route he had taken only a month or so earlier?

The scenario also raises a second question: how did Paul know which way Titus would return to Ephesus? The obvious answer is that Paul had instructed him to return through Macedonia.25 But this only generates another question: why would he have limited Titus’ options in this way? If Paul were as anxious for news as he makes it appear, it would have been more sensible to let Titus make the decision. Under bad conditions a boat could make the transit from Corinth to Ephesus in two weeks. Under optimum conditions the land route of 1,082 km. (676 miles) could not be done in less than five weeks; the average time was probably a couple of weeks longer. It should have been left up to Titus to decide whether the risk of a late crossing was reasonable. Captains did not risk their ships and livelihood stupidly. And Paul was well aware that safety on the roads could not be taken for granted.26 Either way there was danger, and only the person on the spot could weigh the pros and cons.

If Paul ordered Titus not to come by sea, it can only be because he suspected that he might not be in Ephesus when Titus arrived. Paul, in other words, was aware of some danger and had prepared a fall-back position.27 If forced to leave Ephesus, he could be found at Troas, through which Titus would have to come on the overland route. Only when Titus had not appeared, and the sailing season was drawing to a definitive close around mid-September AD 54, did Paul take ship for Macedonia. If he missed the last boat, he would be separated from Titus for the winter, and he would have to wait for news until spring opened the seas to travellers.

Paul’s sojourn in Ephesus had not been without its problems. He was opposed by certain members of the community (Phil. 1: 15–17). He had been imprisoned while under investigation, but whether that is what he meant by the reference to fighting with wild beasts (1 Cor. 15: 32) is an open question. The phrase has to be taken metaphorically,28 but the precise form of the confrontation cannot be discerned. All of that, however, was in the past when he wrote 1 Corinthians, even though he still had enemies in the city (1 Cor. 16: 9).

Presumably it was these latter who were at the root of the ‘affliction we experienced in Asia’, a trial so grave that ‘we despaired of life itself; indeed we felt that we had received the sentence of death’ (2 Cor. 1: 8b–9). The formulation suggests less a juridical condemnation than Paul’s conviction that his days were numbered. The introduction to this episode, ‘we do not want you to be ignorant’ (2 Cor. 1: 8a) indicates that it happened fairly recently and that the Corinthians are being made aware of it for the first time.29 It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that it took place after Paul’s return from the intermediate visit.30 The hints coalesce into a coherent picture. At the time when Titus was despatched to Corinth, opposition to Paul in Ephesus was growing. A sudden intensification of hostility forced Paul to leave the city. He moved north to Troas, where he began a new mission.

In Acts a violent episode—the disturbance instigated by Demetrius, the silversmith (Acts 19: 23–40)—is narrated just prior to Paul’s departure (Acts 20: 1). If this narrative, which is all from the hand of Luke,31 is assumed to be historical and subjected to close analysis, we find ourselves confronted with a whole series of unanswered questions and internal contradictions. The story can only be understood as a vehicle created by Luke to present, in a vivid scene, the rehabilitation of Paul by the authorities of the city, and the victory of Christianity over paganism.32 Luke’s care to anticipate Paul’s departure by noting, in terms which appear to be based on Romans 15: 23–6, that it was planned before the riot, looks like a deliberate attempt to persuade the reader that Paul was not driven out of Ephesus.33 Immediately one suspects that this is exactly what happened!

Two factors influenced Paul’s choice of Troas as the area of his new apostolate. The first was personal; the city had to be on Titus’ return route from Corinth. The second was strategic. The missionary expansion of the church of Ephesus had previously been limited to places within a week’s walk of the city, the capital of Asia.34 Now Paul decided to go further afield, and the two occasions on which he had already passed through Troas had shown him the value of a community there, which could serve as a link between the churches of Asia and those of Europe. Moreover, it would provide him with the large urban environment in which he worked most effectively.

At the time of Paul, Troas was ‘one of the most notable cities of the world’, a Roman colony founded by Augustus and encircled by a massive wall 8 km. (5 miles) long.35 It resembled Corinth in its strategic location as a transit point for trade between Asia and Europe, and was very prosperous.36 Its population has been estimated at between 30,000 and 40,000.37 Paul’s ministry there can hardly have lasted more than a month, but he hints that it was successful—‘despite the opportunity I took leave of them’ (2 Cor. 2: 12–13)—and a Christian community at Troas is presumed by Acts 20: 7–12.

The use of the first-person plural, ‘when we came into Macedonia’ indicates that Paul was not travelling alone. Certainly Timothy was with him (2 Cor. 1: 1). Once the Apostle reached Neapolis, one source of anxiety evaporated; he would not be cut off from Titus for the winter. But, as the days slowly passed, the stress of the delay began to wear him down. He mentions a period characterized by ‘every kind of affliction, disputes without and fears within’ (2 Cor. 7: 5), which was brought to an end only by the arrival of Titus. The strain of the uncertainty of how the Corinthians would react was exacerbated by his fears for the safety of Titus, now seriously overdue, and by squabbles of various sorts.38 Paul by now was in a state of extreme tension where everything was an irritation. His emotional state inflated questions into accusations, and discussions into disputes.

It would have been impossible for Paul to have passed through Philippi without stopping to visit the believers. Were Titus not there, his stay would have been short. It is entirely possible that he had walked the 150 km. (90 miles) to Thessalonica before Titus appeared. The joyful reunion could have taken place anywhere. Now that winter was setting in, Paul and his companions settled down in the nearest community until good weather returned in the spring.

All we have of Titus’ assessment of the situation at Corinth is the version reported by Paul to the Corinthians (2 Cor. 7: 7–16). The presentation is euphoric. Titus had been received in a way which justified the high report which Paul had given him of the Corinthians. The letter he bore, which had been written with such anguish, had achieved its purpose perfectly. The sincerity of the Corinthians’ deep contrition for letting Paul down was underlined by the action they took against the intruder. Now they were totally on his side, and as far as Paul is concerned, ‘I have every confidence in you’ (7: 16).

In view of the shocking explosion which subsequently occasioned 2 Corinthians 10–13, it would be easy to accuse Titus of seeing what he wanted to see, and/or to indict Paul for an overly optimistic interpretation of what Titus told him. This, however, would be a little naïve and fails to do justice either to the intelligence of Titus or to the subtlety of Paul. In 2 Corinthians 7: 7–16, Paul says precisely what the Corinthians expected to hear. They had made an effort, and it was appropriate for Paul to recognize it in the most glowing language possible, particularly since he was going to introduce the topic of the collection for the poor of Jerusalem, with respect to which the Corinthians had not been very energetic (2 Cor. 8–9). There are many hints earlier in 2 Corinthians 1–9 that Titus had been sharply observant, and appropriately critical of what was going on at Corinth,39 and that he reported very accurately to Paul. We must now attempt to reconstruct the gist of what he said.

Once Titus had assured Paul of the affection of the Corinthians, he produced evidence of their change of heart by detailing the action they had taken concerning the individual who had insulted Paul. The nature of the punishment is not specified, presumably because there was but one possibility, namely, complete ostracization. The believers simply refused to have anything to do with him. He was thrown on the mercies of a society which did not care whether he lived or died. Paul had sufficient imagination to feel the impact of such isolation. If he could be thin-skinned and prickly, he could also be generous, and his immediate concern was for the well-being of the offender. The penalty should be lifted and he should be taken back into the community (2 Cor. 2: 6–8).

It seems likely, however, that Paul’s response was not entirely altruistic. It can be seen as an olive branch held out to a group that was still opposed to him, and about which Titus had brought disquieting information. We saw above that the individual who insulted him was in all probability an emissary from Antioch. This is confirmed by the nature of Paul’s response in 2 Corinthians 1–9 to Titus’ news; the intruders were Jewish Christians.40 Only one church would send letters of recommendation to another (2 Cor. 3: 1), and they presented themselves as ‘servants of the new covenant’ (2 Cor. 3: 6). They chose this title in order to harmonize their belief that the eschaton had been inaugurated in Christ with their conviction, inspired by Jeremiah 31: 33, that the Law enjoyed enduring validity.41 Their insistence on the role of the Law is highlighted by the abrupt introduction of ‘on tablets of stone’ (2 Cor. 3: 3) in place of the expected ‘on parchments’.

The Judaizers, however, were not alone in opposition to Paul. There are also hints that point to the spirit-people.42 The accusation that Paul’s gospel was veiled (2 Cor. 4: 3) can only come from those who considered Paul to have an unimpressive personality and lacklustre presentation (2 Cor. 10: 10), i.e. those who preferred the more speculative approach inculcated by Apollos on the basis of Philo. The sophisticated multilayered use of ‘life’ and ‘death’ in 2 Corinthians 2: 16 is adequately paralleled only in Philo (e.g. Fuga, 55), as is the language of 2 Corinthians 6: 14 to 7: 1. The attitude towards the body in 2 Corinthians 5: 6b is typically Philonic.

The simplest and most natural explanation of the mixture of hints pointing to two very different groups is that Titus in his report had linked them as opponents to Paul’s ministry. The mode of reference, moreover, suggests that they did not function as separate groups, but had formed an alliance against him. At first sight an alliance between free-thinking Hellenistic pseudo-philosophic believers, the spirit-people, and Law-observant Jewish Christians seems rather improbable. History, however, abounds in instances of minority groups with radically different aims uniting in order to overthrow a common enemy. When the Judaizers arrived in Corinth, their first act would have been to probe for weaknesses in the community which Paul had built up. In order to work from within, they had to be received by someone, and prudence would have indicated that they search out a group that was already at odds with Paul. In principle it should be more receptive than others to an alternative form of Christianity.43

The spirit-people had been brutally and publicly humiliated by 1 Corinthians. Naturally their pride sought revenge. Had Apollos remained in Corinth, they might have formed an alternative church, but he had left them to join Paul and apparently was not particularly interested in returning (1 Cor. 16: 12). Such betrayal, for which they might have blamed Paul, could only have intensified their bitterness. In this frame of mind, they would have been fair game for any of the Apostle’s opponents. The alliance, in consequence, was one in which both parties gained something. The Judaizers found a welcome among the élite of the Corinthian community, and the spirit-people were given the means of damaging, if not destroying, Paul’s achievement.

In addition to such negative common ground, both groups shared an interest in Moses. For the Judaizers he was the great Lawgiver, whose words had enduring value. For the spirit-people nourished on a form of Philonism, he was much more. Philo regularly presents Moses as the ‘the perfect wise man’ (Leg. All. 1. 395), who epitomized all Hellenistic virtues as ‘king and lawgiver and high priest and prophet’ (Vita Mosis 2. 3; cf. Praem. 53–6). Having alienated himself from the body (Conf. 82), Moses entered into the mysteries of God which, in consequence, he was able to reveal and teach (Gig. 54). In a word, Moses was everything that the spirit-people aspired to be.

It is easy to see how the Judaizers could have exploited this advantage in the interests of their mission. Philo insists on the honour in which all nations hold the Law of Moses (Vita Mosis 2. 17–24), and highlights the providential character of its availability in Greek (Vita Mosis 2. 25–44). The Law has a universal appeal because its statutes ‘attain to the harmony of the universe and are in agreement with the principles of eternal nature’ (Vita Mosis 2. 52), a perspective that is developed in De Decalogo and De Specialibus Legibus. Moses himself was the living embodiment of the Law (Vita Mosis 1. 162); the Lawgiver could not but act in accordance with the revelation he communicated. Others could reach the same heights of religious speculation by accepting the demands of the Law (Mig. 89–94). It is easy to see what attraction this approach would have had for the spirit-people. And once they were committed to Moses, the Judaizers were halfway home.

In order to enhance their appeal to the spirit-people, the Judaizers had to make some concessions. They would have become aware very quickly that the basis of the hostility to Paul among the spirit-people was rooted in his failure to meet their expectations concerning religious leadership. Thus the intruders were led to stress their superior qualifications. They proclaimed their credentials (2 Cor. 4: 5; 10: 12) by advertising their visions and revelations (2 Cor. 12: 1), and their miracles (2 Cor. 12: 12). If they did not know them already, they would have adopted conventions of Hellenistic rhetoric. Themes developed at some length and with a spice of mystery would have flattered the sensibilities of the spirit-people.44

The situation in Corinth, therefore, was anything but happy. The danger was much more insidious than at Galatia. The Judaizers had realized that their frontal attack on Paul had backfired. They were now consolidating their base among disaffected elements in the community. Once that had been achieved they would move into other sectors of the church, in which the ground had been prepared to some extent by Paul’s own attitudes.

Titus had also picked up criticism of Paul’s inability to keep his word. Paul’s vacillation regarding his travel plans was an easy terrain on which anyone with a grievance could score points. Paul had told them one thing (1 Cor. 16: 5–6), and he did not do it. He then promised them something else (2 Cor. 1: 15–16), and failed to do that. What finally he actually did had no resemblance to either; he merely wrote them a letter. The impact of such changes on the Corinthian church was minimal. Paul was not essential, either in theory or practice, to any aspect of its functioning. Why, then, did the changes become an issue?

The way in which Paul replies—‘Do I make my plans like an opportunist, ready to say “Yes, yes” and “No, no”?’ (2 Cor. 1: 17)—clearly indicates that he was being charged with the inconstancy of the flatterer, whose criterion of behaviour is the momentary pleasure of the listener. This is perfectly illustrated by the self-description of a flatterer in Terence’s play, The Eunuch, ‘Whatever they say I praise; if again they say the opposite, I praise that too. If one says no, I say no; if one says yes, I say yes’ (lines 251–3).45 There were people at Corinth saying that Paul was entirely untrustworthy; his word could not be relied upon. In consequence, he could neither be a true friend nor, in this context, an authentic leader. The atmosphere in the community at Corinth was being deliberately poisoned, by continuous sniping at Paul. Titus must have warned him that his every word and gesture was liable to deliberate misconstruction (2 Cor. 1: 12–14). On the basis of what we know already, only the spirit-people had reason to justify such malice.

The same snide attitude surfaces in criticism of Paul’s financial relations with the Corinthians. This had already been an issue at the time of writing of 1 Corinthians, and the spirit-people, who were also the ones most directly involved, now had even greater incentive to use it as a weapon against Paul. It gave them an opportunity to highlight a different aspect of Paul’s inconstancy, and to elevate a hint of untrustworthiness into a charge that Paul did not practise what he preached. He had refused, and continued to refuse, a gesture of love.

The social cement which bound the inhabitants of the Graeco-Roman world together was the reciprocity of benefactions. Seneca in a work devoted to the topic, De Beneficiis, called it ‘the chief bond of human society’ (1. 4. 2). Mere possession of wealth was nothing. It was transmuted into status and power by being distributed.46 A gift was a public gesture laying claim to superiority, and calling for honour from others. For the recipient, ‘no duty is more imperative than that of proving one’s gratitude.’47 The gift had to be reciprocated. If the return was superior in value, the original recipient took the advantage. If of equal value, both remained level. If, however, the return was of less value, the recipient became a client, with an unrequited obligation to the giver. Refusal of a gift, though theoretically possible, was not a real option.

Few were prepared to face the possible or likely hostilities inherent in a refusal. Rather, it was easier to accept an unwanted friendship and let the relationship take its unhappy course. The obligation to receive, then, was generally honoured, even though in many instances, carelessly, foolishly and begrudgingly.48

At Corinth those capable of conferring benefits on Paul were the élite, among whom he had made his first converts.49 Their bid to assist him could be justified, not only by the conventions of the period, but also by the fact that he had benefited them. In Corinth they were his oldest ‘friends’.50 The terminology used by Paul does not permit us to decide whether they offered a gift or a salary.51 The distinction, however, is as irrelevant as any discussion of their motive, because Paul refused. Why did he take a step so much at variance with an honoured custom of his age?52

Paul tells us only that ‘we endure anything rather than put an obstacle in the way of the gospel of Christ’ (1 Cor. 9: 12b). This rather vague justification can be translated into specific reasons only on the basis of what we have seen to be the general principles on which Paul operated. His concern for existential witness guaranteed that he did not want to be compared to those philosophers and religious teachers who expected a return for their teaching. His refusal to conform to their comportment was intended to reinforce the difference in his message. His preoccupation with the unity of the community excluded any action whose result would be to make him a client of one segment of the community.

This latter point becomes clearer if Paul’s refusal of Corinthian support is contrasted with the welcome he accorded subsidies from Philippi, both in Thessalonica (Phil. 4: 16), and at Corinth (2 Cor. 11: 9). The variation in practice has been commented on at length, but the essential point has not been highlighted. While one gift could be presumed to be communal, the other was necessarily individual. Distance made a crucial difference.

The Philippian gift represented a community effort. The church created a common fund to which all could contribute. The sum of money was brought by an official delegation, and presented in the name of the church. The implication, as far as Paul was concerned, was that all members of the church had participated, even though some may have given more than others. The individuality of each contribution was assumed into a whole, which symbolized the unity of the community. Thus the subsidy could be accepted by Paul as an offer of abiding friendship. His response was directed to the whole church (Phil. 4: 10–20).

At Corinth, on the contrary, because Paul lived there, all gifts were highly personal. Benefactions were necessarily particular. Not only because they were handed over by specific individuals, but because they were in-kind. Lodging meant someone’s house, a meal someone’s kitchen. How was Paul to react to a multitude of individual gifts? According to the ethos of society, he would have had to portion out his time and energy in such a way that that those who had contributed the greatest amount received the most. The needy poor would have had little chance against the resources of the élite. Even with the best motives in the world, the wealthy would have monopolized Paul’s attention to the detriment of the real needs of the community. Before he arrived in Corinth Paul must have seen that to accept a single gift would put him in an impossible situation. It is hardly surprising that he repudiated all.

Since the arrival of a delegation from a sister church could hardly be kept secret, there can be little doubt that Paul was forced to explain to the Corinthians why he refused their gifts while accepting that of the Philippians. In the light of 1 Corinthians 9: 1–12a it would appear that he prefaced his explanation with an assertion of his authority by drawing attention to his right to be subsidized. Such a paradoxical approach is unlikely to have enhanced the clarity of his presentation. To those of good will, the distinction between themselves and the Philippians would have made perfect sense. There may even have been some who thought of creating an organization similar to that in place at Philippi, whereby Paul could be helped and the identity of the donors blurred. Others among the élite, however, considered themselves slighted. Their quest for eminence in the community had been frustrated. It was easy for them to ignore the explanation, and to hammer at the facts. Paul refused them while taking from others. The discrepancy then became an opportunity for alternative explanations, none of which was favourable to Paul.

Titus must have been made aware that criticism of Paul had become habitual. His report to Paul, therefore, must have contained some mention of the way the latter’s attitude towards support was being more and more seriously misrepresented.

The reason why Paul did not take up the issue of his personal finances in 2 Corinthians 1–9 was that the question of the collection for the poor of Jerusalem had come up during the visit of Titus to Corinth. The Corinthians had never been informed officially of the collection. They heard of it by accident, presumably from Chloe’s people (1 Cor. 1: 11). Only this explains (a) how Paul could compliment them on taking the initiative as regards participation in the collection (2 Cor. 8: 10); and (b) why they had to request detailed organizational instructions, which Paul provided in 1 Corinthians 16: 1–4. Since Paul’s one concern at the time of writing the Painful Letter was his relationship with the Corinthians, it is most unlikely that he instructed Titus to complicate an already tense situation by raising the question of the collection, particularly since Paul’s attitude towards money was already under fire.53

In discussions with the Judaizers, however, the collection would have furnished a perfect ad hominem argument. The effort that Paul put into it demonstrated in the most practical way possible his love and concern for the Mother Church, which the Judaizers claimed to represent. They could not refuse the gift of the Pauline churches without endangering the survival of their compatriots in Jerusalem, and without putting themselves in precisely the position which the Corinthians found objectionable in Paul. Once Titus was convinced that the Corinthians had accepted the reprimand of the Painful Letter, it would have been natural for him to remind them gently of their commitment to the collection, a gesture which the Judaizers could only second (2 Cor. 8: 6)! In that instant at least, Paul, the Corinthians, and the Judaizers would have been at one, and an enthusiastic note in Titus’ report becomes more understandable.

Paul was fortunate that winter had begun by the time Titus returned from Corinth. Since there was no question of the latter going back there immediately, the possibility of a hasty reaction to the situation at Corinth, similar to 1 Corinthians, was excluded. Paul had time to write and tear up many drafts, before a messenger could get through to Corinth the following spring. At the earliest, the letter was sent in March or April AD 55. Climatic conditions, therefore, forced on Paul a period of reflection on the best strategy to deal with a very complex situation. This time he had the additional advantage of having at his side Timothy, who proved to be a much better co-author than Sosthenes had been for 1 Corinthians.

The contribution of Sosthenes to 1 Corinthians was limited to 1: 18–31 and 2: 6–16. He appears to have been one of those individuals who are briskly insightful in conversation, but who prove to be complicated and overly subtle in formulating a text. Paul gave him two chances, and then in irritation abandoned him; appended to the co-operative sections is Paul’s own frank formulation of what he was trying to get across (2: 1–5; 3: 1–4).54 Timothy was much closer to Paul, and thus had greater influence on him. Manifestly he played a much more significant role in the composition of 2 Corinthians 1–9.

Whereas 1 Corinthians is a first-person singular letter in which it is necessary to explain the irruption of the first-person plural, 2 Corinthians 1–9 is precisely the opposite; 74 per cent of the letter is expressed in the first-person plural, and only 26 per cent in the first-person singular. All the latter passages deal with situations in which Timothy was not involved, namely, the consequences of the intermediate visit (2 Cor. 1: 15–17; 1: 23 to 2: 13; 7: 3–12), and the issue of the collection at Corinth (2 Cor. 8: 8–15; 9: 1–15). The precise reference of the first-person plural can vary,55 but in no case is it necessary to exclude Timothy. He and Paul worked consistently and well together, notably in the major section on the apostolate (2 Cor. 2: 14 to 7: 2), but the nature of some of the material obliged Paul to be highly personal. Such interventions tended to run on a little too long. Each time, however, Timothy was able to get Paul back to the cooperative task, which eventually produced the most extraordinary letter of the New Testament.

In opposition to 1 Corinthians, where Paul jumps straight into the most difficult problem after a rather perfunctory thanksgiving (1: 4–9), which shows his tongue to have been firmly in his cheek,56 2 Corinthians 1–9 begins very cautiously and with a subtlety which sets the tone of the letter. The extremely careful craftsmanship betrays the refinement that is the product of long thought and numerous drafts.

The introductory paragraph begins with a blessing (1: 3) and the idea of thanksgiving appears only at the very end of the paragraph (1: 11). The hint that Paul has deliberately diverged from his customary practice is borne out by a close analysis,

Ordinarily, Paul is the subject of the verb action, here it is the Corinthians; ordinarily, the addressees are referred to in the adverbial phrases, here it is Paul (hyper hêmôn—twice; eis hêmas); ordinarily the principal eucharistô—clause is followed by a final clause, here eucharistô is the verb of the final clause; ordinarily, the eucharistô—clause forms the beginning of the proemium, here it forms the conclusion; ordinarily, the verb is used in the active, here it is used in the passive.57

The Corinthians can hardly have been unaware of the systematic way in which Paul inverted his usual pattern. Many in the community flattered themselves on their intelligence, and they had one if not two letters with thanksgivings in their possession for comparison, namely, the Previous Letter (cf. 1 Cor. 5: 9) and 1 Corinthians. It would have been difficult to avoid the (correct) inference that Paul was sending them a subtle message. First, there is a suggestion that he cannot be unequivocally grateful for the state of the Corinthian church. A breach has been repaired (2 Cor. 7: 5–16), but difficulties remain, and Paul’s subversion of the normal thanksgiving prepares for similar sleight of hand with Philonic terminology in the body of the letter. Secondly, Paul’s unusual focus on his own experience prefigures the major theological theme of the letter, namely, that suffering and weakness, not power and eloquence, are the distinctive signs of the true apostle.

Paul’s two-pronged approach was designed, not only to re-establish his authority, but to drive a wedge between the spirit-people and the Judaizers. If he could rob the latter of their base at Corinth, they would be rendered impotent. Thus, he had to wean the spirit-people away from their guests. To this end he offers a critique of the Mosaic dispensation in terms to which the spirit-people would be particularly sensitive, while at the same time presenting the Christian dispensation in a light which they should find attractive.58

In 2 Corinthians 3: 7–18 Paul focuses on the figure of Moses, which was the lever used by the Judaizers to pry their way into the favour of the spirit-people. The polemic edge of his exposition of ‘When Moses had finished speaking with them he put a veil on his face’ (Exod. 34: 34–5) becomes explicit in the contrast he establishes between his own behaviour and that of Moses, ‘we act with confident boldness, not like Moses who put a veil over his face’ (3: 12–13). The implications are well brought out in a passage from Philo, for whom the theme had special importance:

Let men who do injurious things be put to shame, and seeking hidden places and recesses in the earth, and deep darkness, hide themselves, veiling their lawless iniquity from sight so that no one may behold them. But to those who do such things as are for common advantage, let there be confident openness, and let them go by day through through the middle of the market-place where they will meet with the most numerous crowds, to display their own manner of life in the pure sun. (Spec. Leg. 1. 321; trans. Yonge adapted; emphasis added)

By presenting himself simply as he was, without any pretensions, Paul implicitly claimed a whole range of other qualities, which Moses must have lacked because he dissimulated by veiling himself.

Having thus sown the seeds of doubt in the minds of the spirit-people concerning the stature of Moses, Paul goes on to associate Moses’ achievement with intellectual blindness (3: 14–15). The Judaizers had played into his hands by introducing the idea of a new covenant, for this enabled him to stigmatize the Law as the old covenant, thereby making it supremely unattractive to those who thought of themselves as in the forefront of religious thought. By using ‘Moses’ alone in 3: 15, instead of ‘the book of Moses’ (Esd. 23 [Neh. 13]: 1; 2 Chr. 35: 12), Paul cleverly attaches the pejorative connotation of ‘old’ to the figure of Moses. Paul then goes on to reinforce this point by a subtle adaptation of Exodus 34: 34, which is nothing more than a simple and effective ad hominem argument. The presence of Jews in the Corinthian community showed that they had found something lacking in their previous mode of life based on the Law. They had been blind and now they see. Why then, Paul implies, would the spirit-people want to commit themselves to the darkness of intellectual sclerosis, when they could have the light of authentic glory in the gospel?

In 3: 17 Paul shifts from indirect criticism to seduction by appropriating two key terms in the lexicon of the spirit-people, namely, ‘spirit’ and ‘freedom’. If in 3: 14–15 Paul associated the Law with intellectual blindness, the vice that the spirit-people most despised, here he identifies the gospel with the values they most esteemed. ‘Spirit’ evoked the Philonic heavenly man, and for Philo ‘freedom’ carried the connotations of virtue, perfection, and wisdom.59

This brief summary only hints at the intricacy of Paul’s argumentation. But it is enough to illustrate the change from the brutal tactics of 1 Corinthians. Paul was capable of learning from his mistakes. With the assistance of Timothy, and possibly also of Apollos, he thought his way into the religious world of the spirit-people, and chipped away delicately at their convictions. His subtle denigration of Moses diminished the common ground on which the Judaizers had relied. His reformulation of the gospel was carefully calculated both to harmonize with, and gently but firmly refashion, the Philonic perspective which the spirit-people had received from Apollos. These latter, as Paul presumably realized, would have been constitutionally opposed to the restrictions imposed by the Law. It needed but little to tip the balance against the Judaizers. Paul’s discreet, indirect approach obviated the danger of a perverse reaction such as had been the outcome of 1 Corinthians.

The attitude of the spirit-people to the historical Jesus is summarized by Paul in the shocking phrase ‘Anathema Jesus!’ (1 Cor. 12: 3).60 They found the idea of a crucified saviour repugnant and preferred to think in terms of ‘the Lord of Glory’ (1 Cor. 2: 8), a super-human saviour from above. Paul could not accept this separation of Jesus and Christ, because, as one of Paul’s oldest commentators most perceptively put it, Jesus is the truth of Christ (Eph. 4: 21).61 Only a being of flesh and blood, anchored in space and time, can demonstrate the real possibility of the restored humanity proclaimed in the gospel. Unless the ideal is lived, it remains a purely theoretical possibility, beautiful to contemplate, but without any guarantee that achievement is feasible. Paul, therefore, had to insist that Jesus exhibited love, as opposed to merely talking about it.

Even though the gospels narrated how Christ died on the cross, the preaching tradition of the early church spoke only of the death of Jesus.62 For Paul, this made its reality too easy to ignore, and, in consequence, he consistently insisted that Jesus died in a particularly horrible way, even though he recognized that a crucified Christ was ‘a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles’ (1 Cor. 1: 23).63 The spirit-people preferred to avert their thoughts from this dimension; it cannot be integrated into any philosophical approach to religion. No doubt the Judaizers co-operated. They could assert, with perfect justification, that Paul’s stress on the manner of Christ’s death was exceptional. Moreover, their adaptation to what the spirit-people expected of religious leaders meant a life-style more compatible with that of the Lord of Glory than with that of a tortured criminal.

These attitudes obliged Paul to defend both his ministry and the historicity of Jesus. An integrated approach was indispensable, and the quest forced Paul’s thought into a new dimension. It was in reflecting on the conditions of Jesus’ ministry that Paul saw its relevance to his own situation. In the process he gave new depth to the understanding of Christ’s ministry reflected in the gospel tradition.

The manner of Christ’s ministry was determined by God, ‘For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin’ (2 Cor. 5: 21). In other words, God willed Christ to be subject to the consequences of sin. Jesus was so integrated into humanity-needing-salvation that he endured the penalties inherent in its fallen state. Jesus saved humanity from within by accepting its condition and transforming it. He became as other human beings were in order to reveal to them what they had the potential to become. Thus he suffered as others suffer, and died as others die, even though he in no way merited such affliction.

If 2 Corinthians 5: 21 highlights the divine plan, other texts emphasize the freedom of Christ’s co-operation, ‘he became poor for your sake’ (2 Cor. 8: 9), and the reason for his choice, ‘one died for all’ (2 Cor. 5: 14). His life and death were a deliberate sacrifice of self in order that others might benefit. The fundamental lesson of the self-oblation of Christ is that ‘those who live might live no longer for themselves’ (2 Cor. 5: 15). Prior to Christ it was taken for granted that the primary goals of human existence should be survival, comfort, and success. In the light of Christ’s radical altruism, such a life-style can only be perceived as the ‘death’ of selfishness. It is the antithesis of genuine ‘life’, which is totally concerned with benefiting the other.

The presentation of Christ as ‘the image of God’ (2 Cor. 4: 4) reveals the essence of authenticity to be empowerment, the ability to reach out to enable others.64 In the chapter of Genesis in which this formula appears (Gen. 1: 26–7), God is presented exclusively as the Creator. In consequence, creativity remains the primary referent in determining the meaning of the phrase. Humans resemble God in so far as they are creative. Christ is, like Adam before the Fall, ‘the image and glory of God’ (1 Cor. 11: 7) in the sense that he gives glory to God precisely by being what the Creator intended.

The creative power which made Christ the New Adam (cf. 1 Cor. 15: 45) was exercised in and through poverty and ignominy. His whole existence was a ‘dying’ (2 Cor. 4: 10), but he brought into being ‘a new creation’ (2 Cor. 5: 17). Once Paul had been led to this insight, it was easy for him to see it as the archetype of his own situation. He was conscious of his ‘weakness’ (1 Cor. 9: 22), yet he disposed of a ‘power’ (2 Cor. 4: 7), which created new communities of transformed individuals (2 Cor. 3: 2–3). The basis of Paul’s identification with Jesus, which is the distinctive feature of his understanding of ministry in 2 Corinthians, was their shared experience of suffering.

Hitherto Paul had accepted suffering as integral to the human condition. His experiences would not have set him apart in the ancient world. Life was harsh and survival very much a matter of luck. None of Paul’s acquaintances would have dissented from Homer’s insight, ‘The sorrowless gods have so spun the thread that wretched mortals live in pain’ (Iliad 24. 525). Now Paul saw an opportunity to give meaning to suffering. Even though he thought in terms of his own ministry, his insight is valid for all believers. Suffering can be revelatory when the unchangeable is accepted with grace. If the achievement is disproportionate to the means, the power of God becomes visible.

Paul perceived himself as one of the prisoners of war destined for execution at the climax of a Roman victory parade (2 Cor. 2: 14).65 His first insight is to see his suffering as a prolongation of the sacrifice of Christ. He is ‘the aroma of Christ’ (2 Cor. 2: 15). As smoke wafting across the city from the altar conveyed the fact of sacrifice to those who were not present in the temple, so Paul in his wanderings proclaimed Jesus to the world, not merely in words, but more fundamentally in his comportment. He speaks of himself as ‘always carrying in the body the dying66 of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may be manifest in our bodies. For while we live, we are always being given up to death for Jesus’ sake, so that the life of Jesus may be made visible in our mortal flesh’ (2 Cor. 4: 10–11).

This extraordinary statement is the summit of 2 Corinthians, and the most profound insight ever articulated as to the meaning of suffering and the nature of authentic ministry. Death shadowed Paul’s every step; he could die at any moment. As one headed towards a fate which seemed inevitable, he saw his life as a ‘dying’, which he identified with that of Jesus, who had also foreseen his death (e.g. Mark 8: 31). Paul’s acceptance of his sufferings created a transparency, in which the authentic humanity of Jesus became visible. By grace Paul is what Jesus was.

Paul, however, did not put himself on the same level as Jesus; what he achieved would not have been possible without Jesus. None the less he recognized that, were Jesus to have been the only one to demonstrate the type of humanity desired by the Creator, its revelation could have been dismissed as irrelevant, a unique case without meaning for the rest of humanity. Hence, his acceptance of the responsibility of being Jesus for his converts. The explicitness of this presentation of the minister as an alter Christus is unique in the New Testament. It was forced upon Paul by the spirit-people/Judaizers’ denial of the reality of Jesus’ terrestrial existence and their disparagement of Paul’s ministry.

The initial enthusiasm of the Corinthians for the collection for the poor of Jerusalem had evaporated in the heated atmosphere of the factional disputes within the community. Deeply offended by the way they had been pilloried in 1 Corinthians, the spirit-people, who were potentially the major donors, retaliated by refusing to take part in a project so dear to Paul’s heart. Titus, however, had “won the consent of their allies, the Judaizers, by a clever ad hominem argument, and Paul decided to exploit the opening.

2 Corinthians 8–9 reveals Paul at his best in terms of religious leadership. His consummate skill in the art of persuasion underlines how much he has matured in a single year. Even though he has to stretch the truth to do so, he praises what can be praised—the willingness of the Corinthians (although it was now a year old; 9: 2)—and sedulously avoids even a hint of criticism. He explicitly states that he is not ordering them to contribute (8: 8a), but merely expressing his opinion (8: 10). The example of the Macedonians is introduced in such a way as to permit the Corinthians’ self-respect to function as an internal incentive. In order to assuage any possible anxiety on their part as to the sum expected, he is at pains to emphasize that their attitude is more important than the value of the gift (8: 12). Near the end, however, a hint of the old Paul surfaces in the way he highlights the possibility that he and the Corinthians might be humiliated by the much poorer Macedonian church (9: 4). Fortunately, he immediately excludes the hint of moral blackmail, by denying that he wants to extort money from them (9: 5).

Once before, however, the Corinthians had given their assent and then done nothing. This time Paul was not prepared to rely on words alone, and decided to send emissaries to Corinth, whose presence would be a continuous reminder of his invitation. Even such discreet pressure, however, might be resented by the Corinthians as interference in the internal affairs of a local Church. Paul’s nervousness is palpable in his presentation of Titus. He emphasizes that he is not really sending Titus, as 8: 6 might imply. The latter had volunteered to return to Corinth in response to Paul’s appeal (8: 17)! This little vignette tells us something about Paul’s treatment of his associates. He does not order a subordinate, but requests ‘a partner and co-worker’ (8: 23). Naturally Titus was the bearer of the letter which recommended him so highly.

With Titus will go a brother selected by the churches of Macedonia to act as their delegate in the actual assembling of the money for Jerusalem (8: 19). It is curious that, while his qualifications are given prominence, his name is never mentioned. Many explanations have been suggested,67 but, in the light of the contacts between the Corinthian and Macedonian churches (1 Thess. 1: 7–9; 2 Cor. 11: 9), the simplest hypothesis is that he was a Corinthian Christian, who had gone to aid the spread of the church in Macedonia, and who there had established himself as an exceptional preacher of the gospel. When the Corinthians recognized him, and heard Paul’s eulogy, they would have been both flattered and relieved. Their contribution to a sister church was publicly praised, and Paul’s emissary was not a critical Macedonian (9: 4), but one of their own. His specific role was to guarantee the integrity of the collection (8: 20–1).

The third member of the party (8: 22) is also unnamed. The way he is described suggests that he was a long-time associate of Paul, who had some relationship to the Corinthians. He may have been with Paul on the intermediate visit, or he may have accompanied Titus when the latter carried the Painful Letter. It was Paul’s practice to travel with others, and it is most unlikely that he permitted Titus to go to Corinth alone. A travelling companion was indispensable, not merely to present a stronger front to robbers, but to guard whatever property they had, while the other went to the bath or elsewhere.

According to 2 Corinthians 9: 4, Paul planned to go to Corinth in the near future, i.e. during the summer of AD 55, in order to finalize the collection, on which he had now been working for four years. It would have been clear to him, however, that he could not just breeze in, make contact with the Corinthian delegation, and leave for Jerusalem. Despite his optimistic words in 2 Corinthians 7: 5–16, he was fully aware that the re-establishment of relations with the church left a number of serious problems unresolved. An extended stay was imperative. Exactly how long would depend on circumstances, but he could not risk spoiling the process of reconciliation by fixing a premature departure date. The more he reflected, the clearer it became that he would have to spend the winter of AD 55–56 in Corinth.

The Macedonians, however, might not want to delay. It would be natural to want to be rid as soon as possible of the heavy responsibility represented by the money collected for the poor. Only in summer could they travel to Jerusalem, and the round trip took several months. Any delay now would mean postponing the trip for a year. Hence, the note of hesitation, ‘if some of the Macedonians come with me’ (2 Cor. 9: 4); the matter had not been decided when 2 Corinthians 1–9 was sent.

The more Paul thought about his plans for the future, however, the more reasons he found not to hasten to Corinth. 2 Corinthians 1–9 demanded time for the subtlety of its message to be assimilated adequately. It could only be to Paul’s advantage to have his arguments discussed at length. He could be sure that Titus would nudge reflection in the right direction, and such delicate manipulation should not be hurried. Paul was prepared to find such reasons convincing, because for four years he personally had done little real missionary work. His agents had founded churches in Asia, and he had begun a new community at Troas. This latter episode was brief, and for the most part his energy had been focused on maintaining existing communities. Crisis after crisis in one church or another had demanded his attention. Now all were tranquil. A free summer was a golden opportunity to again seek virgin territory, and to be what he was divinely chosen to be, a founder of churches, who preached Christ where he had not yet been named (Rom. 15: 20). The prospect must have been irresistible. In any case Paul did not restrain himself. He went to Illyricum (Rom. 15: 19).68

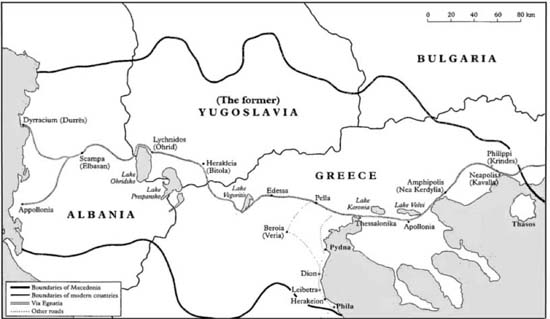

While there might be a slight theoretical doubt as to what precisely Paul meant by this term,69 there is little real uncertainty as to where he was. Wherever Paul and his associates had passed the winter in Macedonia, Paul would certainly have accompanied Titus and his two companions as far as Thessalonica, if they had planned to go south by ship, or to near Pella, if they preferred the land route. To reach virgin territory all Paul had to do was to continue along the Via Egnatia to the west, and in ten days or so he would have been in Illyricum.70 The area is described by Strabo, but in the opposite direction to that travelled by Paul (see Fig. 7):

Of this Adriatic coast, then, the first parts are those about Epidamnus and Apollonia. … From Apollonia to Macedonia one travels the Egnatian Road, towards the east. It has been measured by Roman miles and marked by pillars as far as Cypsela and the Hebrus River—a distance of 535 miles. … And it so happens that travellers setting out from Apollonia and Epidamnus meet at an equal distance from the two places on the same road. Now although the road as a whole is called the Egnatian Road, the first part of it is called the Road to Candavia—an Illyrian mountain—and passes through Lychnidus, a city, and Pylon, a place on the road which marks the boundary between the Illyrian country and Macedonia. From Pylon the road runs to Barnus through Heracleia, and the country of the Lyncestae and that of the Eordi into Edessa and Pella and as far as Thessalonica. And the length of this road, according to Polybius, is 267 miles. (Geography 7. 7. 4; trans. Jones)71

On modern roads, only part of which coincides with the Via Egnatia, the distance between Thessalonica and what Strabo considered the fringes of Illyrian territory is approximately 320 km. (200 miles).72 If Paul set off in mid-April, he would have been among the Illyrians by the end of the month and could look forward to at least three months of intense missionary work before having to head south in August in order to reach Corinth before the onset of winter.

How much Paul had invested in his plans for the summer of AD 55 can be gauged from the depth of his frustration when news from Corinth forced him to change them.

FIG. 7 The Roman Province of Macedonia and the Via Egnatia (Source: F. Papazoglou, ANRW II, 7/1 (1980))

2 Corinthians 1–9, it will be remembered, had two objectives: to drive a wedge between the Judaizers and the spirit-people, and to win the latter to Paul’s side. How well this latter goal was achieved is an open question, but it appears that he did succeed in isolating the Judaizers. Having lost what they hoped would be a firm base at Corinth, the Judaizers could only redouble their attacks on Paul’s person and authority. If there was now little chance of converting the spirit-people into Law-observant Christians, there was always the possibility that they might still be receptive to criticism of Paul.

Titus, or someone sent by him, found Paul in Illyricum and informed him that the old criticism of his unimpressive presence and uninspired preaching (2 Cor. 10: 10) had been revived in a more vicious form. The Judaizers had managed to convince a number that their spiritual gifts raised them far above Paul (2 Cor. 11: 5). The latter’s failure to take strong action during the intermediate visit, they suggested, perhaps indicated that he did not have the authority. Certainly his flight, and failure to return, could only be interpreted as cowardice.

The importance which Paul attached to the collection for the poor of Jerusalem gave the Judaizers the opportunity to highlight his suspiciously ambiguous attitude towards money. He apparently refused money for himself, but solicited it for the poor. Would it all really go to Jerusalem? All the Judaizers had to do, when questioned by the Corinthians about the poverty of the Jerusalem church, was to shrug their shoulders. They did not have to deny the need for the collection. All they had to do was to insinuate that the questioners were a little naïve in taking Paul’s statements at face value. By harping on the fact that Paul had taken money from Philippi (2 Cor. 11: 9), they could make a case that Paul did not love the Corinthians whose generosity he had refused.

Paul could only take such criticisms as a malicious distortion of his motives and actions. His bitter anger was intensified by the awareness that, if he was discredited, his version of the gospel was at risk. Another gospel might take its place. In a mood of desperate anxiety for the future of the Corinthian community, he dashed off 2 Corinthians 10–13. The reasonable tone and subtle arguments of 2 Corinthians 1–9 are replaced by a wild outburst, in which Paul gives his capacity for sarcasm and irony free rein.

The language in which he excoriates the gullibility of the Corinthians is a perfect illustration of the character of 2 Corinthians 10–13, ‘You gladly bear with fools, being wise yourselves! You put up with it when someone makes slaves of you, or eats you out of house and home, or swindles you, or walks all over you, or smacks your face. To my shame, I must say, we were too weak for that!’ (2 Cor. 11: 19–21). The ‘wisdom’ of the Corinthians is to be so lacking in self-respect that they eagerly accept their own exploitation!

What is said in this text has been interpreted literally, metaphorically, and rhetorically.73 A choice between these different options is less important than an appreciation of the quality of the writing.

The style has many impressive features, such as enumeration, as five verbs are listed in succession, and in a climactic way, following the ‘law of increasing members’74 with each verb adding extra weight to Paul’s exposé. The emphasis of a string of verbs, with two hapaxes, found only here in the NT, is enhanced by the anaphorical repetition of [ei] tis five times, ‘the one who,’ and epiphoric assonance (hence the sonorous -oi, -ei, -ei, -ai, -ei).75

The quality of the writing is matched by the authority of the strategy. His opponents have forced him to compare himself with them, and what he does is to display his contempt for their pretensions by turning rhetorical convention upside down. After noting his breeding (2 Cor. 11: 22–3), he goes on to parody the self-display of the Judaizers by highlighting what should be hidden, and minimizing what should be accentuated (2 Cor. 11: 23–30).76 Churches and converts are only hinted at; the spotlight is on situations in which he has been degraded. With great dramatic flair he concludes his list of ‘accomplishments’ with a graphic account of his humiliating escape from Damascus, lowered down the wall like a helpless baby in a basket (2 Cor. 11: 32–3)! He is the antithesis of the winner of the well-known ‘wall crown’,77 which, according to Aulus Gelius, ‘is that which is awarded by a commander to the man who is first to mount the wall and force his way into an enemy town; therefore it is ornamented with representations of the battlements of a wall’ (Attic Nights, 5.6.16; trans. Rolfe).

Parody is not the only weapon in Paul’s rhetorical armoury. He deflates his opponents’ claim to visions and revelations by speaking of his own experience in the third person (2 Cor. 12: 2–4). The technique distances him from the episode, and thereby underlines its irrelevance for his ministry.78 It did not change him in any way, and did not provide him with any information he could use. The criticism of his opponents is all the more effective for being unstated. If their experience was the same as Paul’s, it contributed nothing to their ministry. If it was something about which they could talk, it was less ineffable than his!

2 Corinthians 10–13 is extraordinarily revelatory of a Paul rarely apparent elsewhere. Here the rigid control he normally imposed on his passionate nature dissolves in the heat of his anger. He gives full rein to his emotions, and in so doing betrays the quality of his education, which he usually denied (cf. 1 Cor. 2: 1–5). The fluid creativity of his thought is matched by the masterful facility and freedom with which he employs a number of the techniques of rhetoric. The assurance of his adept use of rhetorical devices can only be the fruit of long study and practice.79 There can be little doubt that Paul was brought up in a socially privileged class, which he was formed to adorn.80

Paul concludes his defence with a rhetorical tour de force, a humble admission which leads into a paradox, ‘And to keep me from being too elated by the abundance of revelations, a thorn was given me, a messenger of Satan, to buffet me, to keep me from being too conceited … when I am weak then I am strong’ (2 Cor. 12: 7–10). The nature of the thorn in the flesh has intrigued commentators from the early patristic period to the present day, and the wide variety of interpretations bears witness to the inexhaustible creativity of the human spirit.81

The vast majority of scholars consider that Paul had a physical ailment or a psychic problem. The suggestions—and they cannot be considered anything more—regarding the latter betray a very refined imagination: a real demon, who accompanied Paul on his heavenly journey, agony at the refusal of the Jews to respond to the gospel, sexual temptations, hysteria, depression. Somatic illnesses appear to have a better foundation: epilepsy (Paul fell to the ground during his conversion, Acts 9: 4), poor eyesight (he desired the eyes of the Galatians, Gal. 4: 15), a speech defect (he made a bad first impression, Gal. 4: 13 ff, and spoke badly, 2 Cor. 10: 10; 11: 6), recurring malarial fever, headache or earache. It will be obvious that the majority of these proposals depend on gratuitous and/or forced interpretations of texts, which are in no way related to physical ailments, be they those of Paul or of anyone else. Moreover, in order to have achieved all that he did, Paul must have been blessed with robust health and a strong constitution.

The only hypothesis for which a serious case can be made is that by the thorn in his flesh Paul meant opposition to his ministry.82 His mention of ‘a messenger of Satan’ implies an external, personal source of affliction, and previously he had identified as ‘servants of Satan’ (2 Cor. 11: 14–15) his adversaries at Corinth. In the Old Testament, ‘thorns’ are a metaphor for Israel’s enemies, both within (Num. 33: 35) and without (Ezek. 28: 24). This latter reference, when coupled with Paul’s use of ‘to buffet’ in 1 Corinthians 4: 11, has been taken to mean that Paul had persecution in mind. I doubt, however, that Paul would have prayed to be delivered from persecution.83 He saw such sufferings as the means whereby he was assimilated to Jesus (2 Cor. 4: 10–11).

What was a continuous source of pain to Paul was the fact that none of his churches measured up to his expectations. There was always someone, in every community he founded, who caused him grief—the idlers at Thessalonica, Euodia and Syntyche at Philippi, those paralysed by prudence in Galatia, the resentful at Ephesus, the mystics at Colossae, the spirit-people at Corinth. There was no grouping of his converts on which he could look with complacent pride. Any tendency to conceit, or even satisfaction, was immediately countered by evidence of some sort of dissent. Such divisions, however, were opposed to the plan of God, for whom the church should exhibit the organic unity of a living body. Hence, Paul could pray legitimately that they would come to an end.