PAUL does not inform us who prevailed in his dispute with Peter at Antioch. His silence, however, tells its own story. Had he won, he could hardly have failed to mention it in Galatians.1 To have been able to assert that Peter had eventually sided with him rather than with James on Jewish practices would have been an important argument against the Judaizing tendency of the churches of Galatia.

The fact that Barnabas had aligned himself with the delegation from Jerusalem left Paul completely isolated. He no longer felt at home in Antioch. The new pattern of its community life reflected an understanding of the gospel with which he could not identify. Its faith was no longer his because, as he saw it, Christ had been moved from his position of absolute centrality. Moreover, Antioch had in effect become a Jewish church. It now mirrored the radical separation between Gentile and Jewish churches, which was the ambition of the nationalistic Jewish Christians, but which was anathema to Paul. He wanted freedom for the Gentile church, but not at the expense of its historical roots in Judaism. He also feared for the Jewish church. His experience as a Pharisee enabled him to foresee what legalism would do to a religious community.

Since the church at Antioch no longer embodied the power of grace, he could not in conscience continue to be its representative in the mission fields to the west (Acts 13: 1–3). We must assume that this troubled Paul on the human level, but it did not paralyse him. From the beginning he had understood his conversion to be a call to preach among the Gentiles. Even if he was no longer the emissary of a church, the divine commission, which had inspired his abortive mission among the Nabataeans, would validate his subsequent career. He was ‘an apostle, not from men or through a man, but through Jesus Christ and God the Father’ (Gal. 1: 1).

Sometime in the spring of AD 52, therefore, when the gorge through the Taurus mountains known as the Cilician Gates was passable, and most of the snow had melted on the plateau, Paul left Antioch. He was never to return.

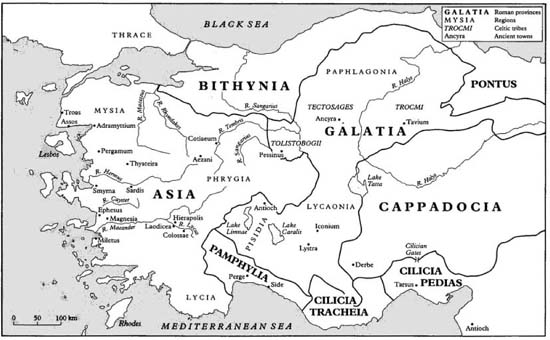

Paul had crossed Asia Minor at least once before, on the journey that brought him to the coast of the Aegean Sea, which he crossed to land at Neapolis the port of Philippi (Acts 16: 11). When dealing with that journey earlier in Chapter 1, my concern was with the time it would have taken him.2 Since the distances were substantially the same, it was not necessary to choose among the routes he might have followed. Only at this stage does the precise route become important because it determines the identity of the converts who most disappointed him, the churches of Galatia (see Fig. 1).

Where was Galatia? Paul tells us only that there was such a place (Gal. 1: 2; 1 Cor. 16: 1), that the inhabitants not surprisingly were called Galatians (Gal. 3: 1), and that his first visit there was the result of an accident (Gal. 4: 13).

We know that Augustus created a Roman province of Galatia. Dio Cassius notes in his report for the year 25 BC, ‘On the death of Amyntas he [Augustus] did not entrust his kingdom to his sons but made it part of the subject territory. Thus Galatia together with Lycaonia obtained a Roman governor, and the portions of Pamphylia formerly assigned to Amyntas were restored to their own district.’3 Amyntas was the last in a series of Celtic rulers stretching back to the third century BC when tribes from the Pyrenees pushed their way into Anatolia.4 The Roman province, however, was greater than the tribal territories. Its southern border englobed Pisidia, Isauria, Lycaonia, and part of Pamphylia.5 In effect, the province was a strip averaging some 200 km. wide running almost the full way across the centre of Asia Minor from north-east to south-west. This means that four towns evangelized by Paul and Barnabas on what Luke presents as the first missionary journey, namely, Antioch in Pisidia, Iconium, Lystra and Derbe (Acts 13: 13 to 14: 28) belonged to the province of Galatia. 2 Timothy 3: 11 confirms that Paul did in fact minister in these towns.

Opinion is divided as to whether by ‘Galatians’ Paul intended converts from these towns (the South Galatia, or province, hypothesis) or from the tribal areas (the North Galatia, or territorial, hypothesis). At one stage it was thought that Paul could not have been so crude as to use the essentially ethnic names of Galatia and Galatians of those who were not Celts.6 Respectable citizens of Pisidia and Lycaonia, it was implied, would not appreciate being identified as wild barbarians! More recent studies, however, have removed this apparently plausible argument from contention. ‘There are even some hints, contrary to views often repeated, that the term “Galatian” was a correct and honourable title especially acceptable to the more Hellenized or Romanized people in the province.’7 As far as linguistic usage is concerned, therefore, Paul’s letter to the Galatians could have been written to a group of communities anywhere in the Roman province.

Fig. 1 Asia Minor at the Time of Paul (Source: Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients, BV7 (1983))

This point is developed very adroitly by Burton, ‘if the churches addressed [in Gal.] were those of Derbe, Lystra, Iconium and Antioch, which he [Paul] founded on his first missionary journey, he could not address their members by any single term except Galatians.’8 We are invited to admire how cleverly Paul glosses over the differences between these churches by finding a common denominator in their belonging to the same Roman province. But is it really likely that Paul would have written a single letter to so many and so diverse churches? The improbability is accentuated by their dispersion. Derbe is 286 km. (172 miles) from Antioch in Pisidia.9 In Macedonia, even though Thessalonica and Philippi are only half that distance apart (166 km., 100 miles), and even though the same type of Judaization was a threat (Phil. 3: 2), Paul deals with each church individually.

Moreover, according to Galatians 4: 13, Paul’s first visit to the Galatians was hot planned. It was the result of an accident; he fell sick and they nursed him back to health. This fact has not escaped the partisans of the North Galatia hypothesis. But they develop it into an argument only by contrasting Paul’s account of his condition with Luke’s presentation of missionaries so dynamic that they are taken for gods (Acts 14: 12). While it is easy to imagine reasons why Luke would have passed over an illness in discreet silence, it is much more difficult to explain why Paul himself would omit such a trial in his list of the difficulties he experienced in South Galatia (2 Tim. 3: 11). The way in which he speaks of the problems occasioned by an intensely active ministry there excludes a period of illness so serious that he was a grave burden to the Galatians (Gal. 4: 14).

If the Galatians to whom Paul writes are unlikely to be the believers in the southern part of the Roman province, where did they live? Luke provides a possible answer. With regard to Paul’s journey to Ephesus, he tells us that ‘he went through the region of Galatia and Phrygia strengthening all the disciples’ (Acts 18: 23).10 The impression given is that he retraced the route he and Timothy (at least) had taken previously from Lystra, ‘they went through the region of Phrygia and Galatia having been forbidden by the Holy Spirit to speak the word in Asia’ (Acts 16: 6). The inversion of the words Phrygia and Galatia and the fact that both can be used as adjectives strongly suggests that Luke has in mind territory which was both Phrygian (by language and culture) and Galatian (by Roman administrative fiat).11

The description applies perfectly to the territory in which Antioch in Pisidia and Iconium were located, but it is unlikely that this is what Luke had in mind. Paul must have reached Antioch in Pisidia, the last major town in Galatia, when he realized that he was not going to be able to cross over into Asia. The alternative he chose was to go through Phrygio-Galatian territory, namely, the border area between Asia and Galatia north of Antioch in Pisidia, which would bring them to a point east of Mysia and south of Bithynia (Acts 16: 7).12

What is known of the routes, however, indicates that it would be more natural to travel on the Phrygian side of the border.13 Only south-east of Pessinus (modern Balahisar) would it have been easy to make a diversion to the east, which would have brought him within Galatian tribal territory. But why would Paul make a turn diametrically opposed to his planned journey to the west? It is impossible to find motivation for a change of plan. Something must have happened to force Paul to abandon temporarily his project to work his way around Asia. The illness he mentions (Gal. 4: 13) is such an explanation, but to speculate on what it was and how it changed his plans is fruitless. Hence it seems most probable that the Galatians to whom Paul wrote were inhabitants of the north-eastern corner of Galatia, the almost square territory bordered on three sides by the immense bend of the river Sangarios (modern Sakarya).

We have seen that the letters suggest that after Galatia Paul evangelized Macedonia.14 The Apostle gives no hint of the route he took. Luke, however, tells us that ‘passing through Mysia they came down to Troas’ (Acts 16: 8).15 Even though Mysia was part of Asia, its relation to the province paralleled that of Judaea to the province of Syria; it was treated as a separate district and ruled by a procurator.16 Thus Paul and his companion(s) could go through Mysia without encountering any official obstacles, if it were such which prevented them from entering Asia. The route they took can only be a matter of speculation, even if one were sure that they were heading for Troas.17 From Luke we know only that this is where they ended up. There were three possible western routes from Galatia.

A northern route from Cotiaeum followed the valley of the Rhyndacos to reach the Sea of Marmora east of Cyzicus whence there was a road to the west linking the little harbours along the Hellespont.18 If Paul’s intention was to cross over to Macedonia, his reason for bypassing these ports can only have been lack of shipping and/or contrary winds. The least probable is a postulated central route also starting in Cotiaeum and running almost due west through what later became Hadriania, Hadrianutherae, and Scepsis whence it followed the valley of the Scamander to Illium and the coast road.19 The terrain is very difficult and the eastern part was notorious for its brigands.20 The best route apparently was the southern one. From Cotiaeum it ran south-west to Aezani and then across to the headwaters of the Macestus, which the traveller followed to Hadrianutherae, whence there was a good road to the port city of Adramyttium.21 Both it and Assos (Acts 20: 13) would have been convenient only for a sea voyage south along the coast of Asia. Anyone wishing to sail north or west would have made for Troas.

Some years later when Paul was concerned about news from Corinth which he expected to come through Macedonia, he went to Troas; when the messenger was delayed, he crossed from there (2 Cor. 2: 12–13). Evidently both Paul and Luke knew that Troas was the normal departure point for Europe, and the port of entry into Asia for those sailing from Neapolis the eastern terminal of the Via Egnatia, which crossed northern Greece. The absence of any letters to churches in Mysia suggests, either that Paul made no attempt to evangelize that area, or that he failed disastrously. Only his lack of success at Athens confers any plausibility on the latter hypothesis. That failure, however, was completely atypical, and was due to a combination of circumstances, the arrogance of the Athenian closed mind and Paul’s anxiety concerning the Thessalonians.22 We should assume, therefore, that Paul marched through Mysia without stopping to preach. If this is correct, it necessarily implies that when he left Galatia he had decided to go to Troas precisely in order to take ship for Europe.23

If at first sight shocking and inexplicable, on reflection Paul’s decision to leave Asia Minor reveals a deliberate missionary strategy and provides confirmation of the accuracy of the basic thrust of Luke’s narrative (Acts 16: 6–12). The communities at Antioch in Pisidia, Iconium, Lystra and Derbe were well established. Paul had high hopes for his new foundations around Pessinus. The faith, in his estimation, was well planted in Galatia, the central province of Asia, whence it could radiate out in all directions. And he was convinced it would. Imbued as he was with his own profound sense of mission, he could not but take it for granted that his converts would be aggressively apostolic. The best course for him, therefore, was to move west beyond the furthest missionary reach of the Galatian churches.

Paul’s strategy in Greece, it will be recalled, was essentially the same. There, however, instead of capturing the middle, he established bases at the extremities, in Macedonia (Thessalonica and Philippi) and in the Peleponnese (Corinth). Even though he walked the length of the country several times, he made no attempt to evangelize Thessaly. In his view, central Greece was the missionary responsibility of the churches which bracketed it on the north and south. At a later stage, when he had done all he could for Corinth, Paul planned to leap-frog over Rome to preach in Spain (Rom. 15: 24), the western edge of the known world.

The optimism of this vision was not justified by events. Paul’s experience of the growing pains of the church of Thessalonica had made him conscious that founding churches was not enough. They had to be nurtured. Children in the faith needed time to grow, and in the process ‘proclamation’ had to be complemented by ‘teaching’. What had happened at Antioch-on-the Orontes brought it home to him even more clearly that the development of a church could not be taken for granted. Thus when he crossed Asia Minor for the second time maintenance had become more important than outreach, at least for the time being.

Luke’s economy with the truth as regards Paul’s reason for leaving Antioch gives way to perfect accuracy when he depicts him as meticulously visiting each place in Galato-Phrygia where a community had been established (Acts 18: 23).24 We know from the letters that Paul passed through Galatia at least twice (Gal. 4: 13) prior to writing Galatians. He founded churches there prior to the conference in Jerusalem (Gal. 2: 5) and subsequently organized the collection for the poor of Jerusalem which was agreed on at the conference (1 Cor. 16: 1).

It is, of course, possible that he invited the Galatians to participate in the collection by letter, but it is much more probable that he did so in person.25 The wind pattern during the sailing season made it preferable to cross Asia Minor from east to west by foot rather than sail round it by ship. The long dusty roads might be wearying, but one could make steady progress. Ships dispensed the traveller from personal effort, but the winds were predominantly adverse for those coming from the east, and headwinds forced boats to anchor for days, if not weeks, on end as they inched their way along the south coast of Asia Minor.26 It was the opposite for those going from west to east, which is why Paul always returned home by ship (Acts 18: 18–22; 20: 6 to 21: 3).27

It is virtually certain, therefore, that since Paul had been in Galatia (1 Cor. 16: 1) prior to his arrival in Ephesus (1 Cor. 16: 8) his route to the west took him through the anôterika merê. Literally ‘the upper parts’,28 this unparalleled expression may simply be a way of speaking about the Anatolian plateau, which is also the interior of Asia Minor, but Hemer follows Ramsay in giving it a more specific sense as evoking ‘the traverse of the hill-road reaching Ephesus by the Cayster valley north of Mt. Messognis, and not by the Lycus and Maeander valleys, with which Paul may have been unacquainted’.29 This route becomes plausible only if it is assumed that Paul was coming, not from Antioch in Pisidia, as Hemer’s South Galatia hypothesis requires, but from somewhere much further north, such as the region around Pessinus.

What has been said above regarding Paul’s missionary strategy prohibits adopting Hemer’s confirmatory argument, namely, that Paul could not have passed through the Lycus valley because he had not preached there (Col. 2: 1). At this point in his career, Paul was concerned with stabilizing established existing communities, not with founding new ones. Thus even if he had taken the great common highway to the west via the Lycus and Meander valleys,30 he would not have stopped along the way to evangelize. His goal was to reach Ephesus.

Paul’s choice of Ephesus for his second long-term base was as well thought out as his earlier selection of Corinth. The centrality of this city on the western coast of Asia Minor with respect to churches he had previously founded is well illustrated by some simple statistics. As the crow flies, Ephesus is equidistant from Galatia and Thessalonica (480 km., 288 miles). Corinth (400 km., 240 miles), Philippi (445 km., 267 miles), and Antioch in Pisidia (330 km., 198 miles) fit easily within the same circle. Paul himself does not tell us how long he stayed in Ephesus. Luke gives two figures, first two years and three months (Acts 19: 8–10), and later three years (Acts 20: 31). The latter is a round figure, but the specificity of the former inspires confidence. If Luke’s information were not available, a similar figure would have to be postulated in order to allow time for the activities of Paul which can be deduced from the letters.

The oldest remains of the city date from the mid-second millenium BC. Its antiquity is confirmed by the mythical origin of its name. According to Pausanias, it was called after Ephesos, who was believed to be the son of the river Cayster.31 Around 286 BC the city was given its present location (between the hills now named Bülbül Dagh and Panayir Dagh) by Lysimachus (360–281 BC), a companion and successor of Alexander the Great. The majesty of the wall he built (7 m. high, 3 m. wide, and 9 km. long) was accentuated by its position on the crests of the hills; sections still exist. His purpose in moving the city to the west was to compensate for the silting up of the river valley.32 He did not solve the problem which, according to Strabo,33 was exacerbated by one of his successors, who, by ordering a badly placed breakwater, intensified the silting up of the harbour called Coressos.34 There was another harbour named Panormus further to the west.35 A functioning port was essential if Ephesus was to realize its full economic potential, and inscriptions36 confirm that the proconsul Barea Soranus in AD 61 was not the only one to have seen the necessity of periodically dredging the harbour.37

In 133 BC by the testament of Attalus III (170–133 BC) Rome acquired the kingdom of Pergamum, which became the province of Asia.38 It had a stormy history until Octavian succeeded in establishing control. Even though Pergamum remained the titular capital, Ephesus was in fact the more important city.39 This undoubtedly influenced the decision of Augustus to make it the seat of the proconsul. He also saw the opportunity to enhance his own glory by ensuring that Ephesus blossomed with magnificent buildings.40 The Attalids had made Pergamum one of the most beautiful of Greek cities, whereas the possibilities of the grid plan of Lysimachus at Ephesus had never been fully exploited.41

A number of notable buildings are dated to the reign of Augustus,42 and were a dominant feature of the city at the time of Paul (see Fig. 2). One complex in the southern part of the city contained the town-hall, the double temple dedicated to Rome and Julius Caesar, and a 200 metre-long open basilica which filled the northern side of the State Agora. Ceremonial gates gave dignity to the south entrance of the Square Agora (112 × 112 m.) and to the west end of the great street running from the theatre to the harbour. Three new aqueducts, the Aqua Julia and the Aqua Troessitica, to which the emperor contributed, and the aqueduct of C. Sextilius Pollio both improved the quality of life in the city and provided for an expansion of the population.43 They also facilitated the construction of baths cum gymnasia (six are known), in which the social life of the Roman city was concentrated.

The stage area of the great 25,000-seat theatre (Acts 19: 31) was expanded not long before Paul’s arrival.44 The only other monument to rival it in size was of course the temple of Artemis (Acts 19: 35). Rebuilt many times since its foundation in the seventh century BC,45 it quickly found its place in the earliest lists of the seven wonders of the world.46 In the early second century BC Antipater of Sidon wrote,

I have set eyes on the wall of lofty Babylon, on which is a road for chariots, and the statue of Zeus by the Alpheus [at Olympia], and the hanging gardens [of Babylon], and the colossos of the Sun [at Rhodes], and the huge labour of the high pyramids [in Egypt], and the vast tomb of Mausolus [at Halicarnassus], but when I saw the house of Artemis that mounted to the clouds, those other marvels lost their brilliancy, and I said, ‘Lo, apart from Olympus, the Sun never looked on aught so grand’. (Greek Anthology 9. 58; trans. Paton)

FIG. 2 Central Ephesus c. AD 50 (Sources: W. Alzinger, PW Sup. XII; W. Alzinger, ANR W II, 7/2 (1980))

This temple measured 115 × 55 m., and the 98 colums in the double row surrounding the building were 17.65 m. high.47 The pilgrims it attracted to Ephesus were an important factor in the economy. It survived until the third century AD.

If such majestic structures contributed to the ethos of the city, they were not where the inhabitants lived. Private dwellings tell us much more about the conditions under which Paul operated. Two complexes have been excavated on the slope of Bülbül Dagh, south of the street linking the Square Agora and the State Agora.48 First built in the first century BC, the quality of construction was such that they were still in use 600 years later, though often repaired. The ground floor of the eastern complex spread over 3,000 sq. m. and was the house of a single very wealthy family.49 Its spacious and numerous public rooms would have been a boon to the nascent Christian church, but such magnates were rarely if ever to be found among its members.

Those who could afford to host the liturgical assemblies of the community were much more likely to have lived in a house similar to one of the seven two-storey dwellings in the western complex (see Fig. 3). The ground floor area of House A is 380 sq. m.50 From the right of the vestibule a door leads to the Roman bath, which also heated the house. Directly ahead is the atrium (7.5 × 5 m.) with its impluvium (3 × 3.75 m.). A small room on one side gives access to the dining room (3 × 5.5 m.); the kitchen is nearby. A much larger room (6.5 × 4.25 m.) is entered directly from another side of the atrium through a large arched doorway.

These were the public rooms; the rest of the house was off limits to casual visitors. The size of the rooms meant that once the Christian community reached a certain size complications were inevitable. When it became impossible to get everyone into the same room, there was a danger of creating first-and second-class members, which in fact happened in Corinth (1 Cor. 11: 17–34).51 Inevitably there was a tendency to meet in smaller groups, such as the house-church which assembled in the home of Prisca and Aquila (1 Cor. 16: 19).

The heterogeneous character of the population of Ephesus needs no emphasis. It was the door to the west for the Anatolian hinterland, and the opening to Asia for Greece and Rome. Many went no further. It was as much a melting-pot as Rome itself.52 The population is estimated at a quarter of a million. Citizens in the strict sense (i.e. with voting rights) were perhaps a quarter of that figure. In the light of our present knowledge, it seems that there were nine ‘Tribes’ each with six ‘Thousands’.53

FIG. 3 Ephesus: Private Houses (Source: S. Erdemgil et al., La maisons du Plane à Ephese (Istanbul, 1988))

When Paul headed for Ephesus in the summer of AD 52,54 he was not venturing into the unknown. According to Luke, he had made a brief stop there en route to Palestine, after founding the church at Corinth (Acts 18: 19). More importantly he had prepared his welcome by leaving there Prisca and Aquila (Acts 18: 24–8), the couple who had provided him with a base when he first went to Corinth (Acts 18: 2–3). This means that they had been there for a year prior to Paul’s arrival after the Jerusalem Conference. It is extremely improbable that they had devoted all their energy exclusively to re-establishing their tent-making business. They had been Paul’s partners in the evangelization of Corinth, and preaching the gospel would have become second nature to them by now. Even while at work, they would have availed of every opportunity to proclaim the good news. Prisca, and Aquila, therefore, were the real founders of the church at Ephesus.

The reliability of Luke’s information regarding the precedence of the couple in Ephesus is confirmed by the fact that it embarassed him. This is clear from the curious note, ‘They [Paul, Prisca and Aquila] came to Ephesus, and he left them [Prisca and Aquila] there, but he himself went into the synagogue and lectured to the Jews’ (Acts 18: 19); the reason for the emphatic ‘he himself can only be to drive home the fact that it was Paul who delivered the first missionary sermon in Ephesus.55 Such insistence, however, hints that the real situation may have been rather more complex.

Were Luke free to create, he would have made Paul directly responsible for the evangelization of Ephesus. Luke’s concern, it will be recalled, was to tie the foundation of the church there into a pattern of controlled expansion, and Paul’s missionary role had been formally accepted by Jerusalem (Acts 15). It was definitely not in Luke’s interest to invent the activity of people such as Prisca and Aquila. It was a fact that he had no choice but to integrate. And he did so in a way which probably corresponds to reality. The couple, he insinuates, were acting in collaboration with Paul.

The letters confirm this inference. We can deduce from 1 Corinthians 16: 19, not only that Prisca and Aquila had moved from Corinth to Ephesus, but that they were very close to Paul. This verse is the most complex closing greeting in the Pauline epistles. The first of the three sources of greetings is the churches of Asia, which is perfectly appropriate in an official letter written from the first city of Asia (1 Cor. 16: 8). The second is Prisca, Aquila and their house-church, and the third is all the believers. The order is intriguing. Manifestly it was Paul’s intention to mention only the churches of the province of Asia, for the reason given above. The abrupt shift from this impersonal level to the intimate level of a particular couple suggests that Aquila and/or Prisca were present as Paul ended the letter, and felt close enough to him to ask to be mentioned. The most plausible motive for such an interjection, namely a previous connection with the Corinthians (cf. Acts 18: 1–3), is confirmed by the qualification of their greeting as ‘hearty’; it was not a mere ceremonial gesture.56 The mention of their house-church in turn stimulated Paul to include a reference to ‘all the believers’, i.e. the ‘whole’ church (1 Cor. 14: 23).

No sooner had the Christian mission in Ephesus begun than an unusual phenomenon occurred. To their immense surprise the missionaries came into contact with people who already knew Jesus! The discussion of Acts 18: 24 to 19: 7 has given rise to a lively debate,57 which has been perfectly characterized by Käsemann in his best mordant style, ‘This conspectus has brought before us every even barely conceivable variety of naivete, defeatism and fertile imagination which historical scholarship can display, from the extremely ingenuous on the one hand to the extremely arbitrary on the other.’58

Such confusion, I suggest, is due to a false perception of the problem. At the risk of some simplification I think it fair to say that all interpretations wrestle with the question: how could ‘followers of John’ be classified as ‘disciples’ and ‘believers’, i.e. as Christians? Research has been side-tracked by this formulation of the problem, which is inaccurate. Despite the title of so many articles, it is neither said nor suggested anywhere in the text that Apollos and the others were disciples of John. They had received the baptism of John, and the real question is: who administered it?

In the light of John 3: 22 the obvious answer is that it was administered by Jesus when he was preaching John’s baptism of repentance in Judaea. The language of John 3. 22 contradicts R. Schnackenburg’s gratuitous assumption that the period must have been very short.59 On the contrary, the success of Jesus is explicitly emphasized (John 3: 26). There were many, therefore, who thought of themselves as followers of Jesus and in consequence were accepted as ‘believers’ at Ephesus (and elsewhere) until somehow their baptism and/or the content of their belief was questioned. They were disciples of Jesus of Nazareth (in the sense of having been converted to repentance by him), but had known him only while he was still associated with John, and had lost contact with him subsequently. They had vivid memories of Jesus as the assistant of a prophet, but knew nothing of the Passion, Resurrection, or Pentecost. It is most unlikely that they thought of Jesus as the Messiah.

Inevitably the relation of such people to Jesus would have been suspect to those who knew him as the Risen Lord. Some action was imperative if there were not to be two radically different types of followers of Jesus. The natural assumption is that Prisca and Aquila invited them to become full believers, and that those who accepted were baptized. The scenario of Acts is predictable in that it makes Paul the instrument of their conversion, but Luke adds a further dimension which suggests a new Pentecost (Acts 19: 5–7; cf. 2: 4).

One of those who had received the baptism of John and who had ended up in Ephesus, according to Luke, was Apollos, a well-educated Jew from Alexandria (Acts 18: 24). For their part, the letters reveal that an Apollos had ministered in Corinth (1 Cor. 3: 6) and that subsequently he was with Paul at Ephesus (1 Cor. 16: 8, 12). As we shall see when dealing with the Corinthian correspondence, this Apollos was a trained orator acquainted with the teaching of Philo of Alexandria. There is little doubt, therefore, that we have to do with the same person.60

Apart from this group, nothing specific is known about the composition of the church at Ephesus. Since the city was similar to Corinth in so many ways we can assume with some confidence that the two communities resembled each other in both size and make-up (1 Cor. 1: 26–9). Each was the city in microcosm; a few relatively wealthy members, the majority tradespeople and slaves, possibly more women than men.

The success of Paul and his collaborators in establishing a flourishing community in Ephesus had unexpected side-benefits in the foundation of churches elsewhere in the province. The hyperbole of Acts 19: 10 and 26 is lacking in the Pauline letters, but the existence of Christian communities outside Ephesus is attested by the greetings which ‘the churches of Asia’ (1 Cor. 16: 19) send to Corinth. The only names of such churches known to us from the Pauline letters are Colossae, Laodicea, and Hierapolis (Col. 4: 13), but it would be unwise to assume that this list is exhaustive. These three are mentioned only because Paul had to ensure that neighbouring churches were not infected by the false teaching which had divided the church at Colossae.

Paul himself did not found the churches of the Lycus valley (Col. 2: 1). In the thanksgiving of Colossians, he speaks of ‘the day you heard and understood the grace of God in truth as you learned it from Epaphras our beloved fellow-slave. He is a faithful minister of Christ on our/your behalf and has made known to us your love in the Spirit’ (Col. 1: 6–8). In Colossians 4: 12, Epaphras is identified as ‘one of yours’, which is reasonably interpreted as meaning that he came from Colossae. From the compliment ‘he has worked hard for you and for those in Laodicea and in Hierapolis’ (Col. 4: 13), one can deduce that he was the founder of all three churches.

Was Epaphras acting on his own initiative or as Paul’s agent when he evangelized the Lycus valley? The question is not really answered by a simple choice among the variants in Colossians 1: 7 on the basis of the manuscripts. Even if Epaphras were Paul’s deputy, the latter could still speak of him as the representative of the Colossians in expressing their affection for the Apostle. Were this Paul’s meaning, however, it does not seem likely that he would have called Epaphras ‘a faithful minister of Christ on your behalf (Col. 1: 7); the italicized genitive is not appropriate to a messenger from the Colossians (cf. Phil. 2: 25).61 It rather suggests a duly authorized missionary, i.e. one sent by Paul (cf. 2 Cor. 11: 23). This is confirmed, not only by Paul’s use of ‘minister’ and ‘slave’ elsewhere to identify his own role as an apostle, but particularly by the combination ‘faithful minister and fellow-slave’, which in this letter is applied to Tychicus (Col. 4: 7), who was certainly Paul’s emissary (Col. 4: 8). The fact that Epaphras was imprisoned with Paul (Philem. 23), whereas Epaphroditus was not (Phil. 2: 25), indicates that the authorities understood the former to be Paul’s agent. It is more probable, therefore, that ‘on our behalf should be read in Colossians 1: j.62 The warmth with which Paul speaks of Epaphras reveals his confidence in him. Epaphras could not have been responsible for whatever problems had arisen in Colossae. His relationship to Paul probably typifies that of the missionaries who were sent elsewhere in Asia.63

The fact that Paul himself did not go to the Lycus valley confirms what has been said above regarding his commitment to nurturing already existing communities. But if the demands on his time at Ephesus, and restrictions on his freedom of movement (see below), precluded missionary travel, he could commission others to preach in his name. Paul had at last learnt, not only that he could not do everything, but that he did not even have to try. It is unlikely that Epaphras was the only missionary sent out from Ephesus, and it is far from impossible that most if not all of the churches in western Asia were established as part of the planned outreach of the Ephesian community guided by Paul.

If Ephesus and Laodicea, two of the seven churches of the Apocalypse (Rev. 2: 1 to 3: 22), were Pauline foundations (the latter at least indirectly through Epaphras), then there is no obstacle to attributing the creation of communities at Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, and Philadelphia to the missionary initiative of Ephesus. To these might be added Magnesia and Tralles, whose churches are known from the letters of Ignatius. All are within a 192 km. (120 mile) radius of Ephesus, and linked by major roads. Colossae, the furthest away, could be reached in a comfortable week’s walk from Ephesus.

The absence of any letters from Paul to these churches cannot be construed as an objection to their Pauline origin. There are many possible reasons for his silence, but the simplest is that he had adopted a policy of delegation. He trusted the missionary responsible for a particular church to deal with whatever issues arose there. No doubt he was available for consultation, but he maintained direct contact only with the churches he had founded personally.

The letter to the Colossians is an exception to this self-imposed rule, but one which is easily explained. Epaphras had gone to Ephesus to inform Paul of the situation at Colossae and to develop a strategy for dealing with the false teaching which attracted some members of the church. There he found Paul a prisoner (Col. 4: 10, 18) and was himself held for interrogation by the Roman authorities (Philem. 23), which prevented him from returning to Colossae (Col. 4: 12–13). The defection of one of the leadership group there made it imperative to deal promptly with the situation.64 Paul had only two alternatives, either a messenger or a letter. The former apparently was not a viable option; none of Paul’s collaborators, who was free to undertake the task, had the authority that the situation demanded. A letter was the only option, and it was written by Paul to give it the greatest possible weight.

The scenario just outlined assumes that Paul was imprisoned in Ephesus. According to Acts, however, his sojourn in the city was entirely peaceful, with the exception of the riot of the silversmiths, which did him no damage; the only imprisonments mentioned in Acts are those at Philippi (Acts 16: 23), Caesarea (Acts 23: 23 to 26: 32), and at Rome (Acts 28: 16). It is not surprising, therefore, that from the beginning of patristic exegesis it was taken for granted that the letters in which Paul says that he is a prisoner (Eph., Phil., Col., and Philem.) were written in Rome.65 Only in the twentieth century did Caesarea Maritima in Palestine, and Ephesus surface as rivals to the Eternal City. Caesarea has won very little support because all the arguments invoked in its favour carry greater force when applied to Ephesus.66 Moreover, we know from Paul himself that he experienced a life-threatening situation in Ephesus (1 Cor. 15: 32; cf. 2 Cor. 11: 23).67 The choice, therefore, is between the capital of Asia and Rome. Unfortunately the decision must be based on vague and often ambiguous hints in the letters.

Although very different in content, Colossians and Philemon were written in identical circumstances to groups which overlapped considerably. In both letters Paul is a prisoner (Col. 4: 10–18; Philem. 1, 9, 23). In both he is accompanied by Timothy (Col. 1: 1; Philem. 1), Epaphras (Col. 4: 12; Philem. 23), Aristarchus (Col. 4: 10; Philem. 24), Mark (Col. 4: 10; Philem. 24), Luke (Col. 4: 14; Philem. 24), Demas (Col. 4: 14; Philem. 24), and Onesimus (Col. 4: 9; Philem. 10–12).68 In both Archippus appears among the recipients (Col. 4: 17; Philem. 2). ‘These agreements do not occur in the same relationships and formulations, however, so that the thesis is unconvincing that the indubitably Pauline Philem. has been imitated by a non-Pauline writer only in these personal remarks.’69 Three facts indicate that the house-church of Philemon was at Colossae: (1) Epaphras of Colossae knows the recipients of Philemon well enough to send greetings (Philem. 23); (2) Onesimus was from Colossae (Col. 4: 9); (3) Archippus of Colossae is among the recipients of both letters. Hence information from one letter can be used to supplement that of the other.

According to the dominant interpretation of Philemon, Onesimus, one of the bearers of Colossians, was a runaway slave who, after encountering Paul in the city in which the latter was imprisoned, was sent back to Colossae. Where had he taken refuge? It is both unreasonable and unnecessary to assume that he went all the way to Rome. The long journey involving two sea voyages was an expensive undertaking, which can only be made plausible by assumptions regarding stolen funds, or a new employer who just happened to be heading for the centre of the empire, which in turn demand other assumptions. In order to be safe Onesimus did not have to go very far. There was no police force constantly on the alert for fugitives.70 Reward notices might be published,71 but, unless the authorities were pressured by someone of irresistible influence, that was the only action they would normally take, and one cannot imagine the notices being distributed outside the immediate locality. Once in Ephesus, Onesimus would have been perfectly sure that there was only the slightest chance of being discovered. A chance encounter with an acquaintance of his master was his only danger.

Was it just bad luck that brought Onesimus into Paul’s orbit? Or did he go looking for him? P. Lampe has drawn attention to a provision of Roman law which permited a slave in danger of punishment to seek out a friend of the owner to act as an intermediary in the re-establishment of good relations.72 Under such circumstances the slave did not become a fugitive in the legal sense. If he went to a friend of the owner, no intention to escape could be assumed. The situation is perfectly illustrated by a letter from Pliny the Younger to Sabinianus.

The freedman of yours with whom you said you were angry has been to me, flung himself at my feet and clung to me as if I were you. He begged my help with many tears, though he left a great deal unsaid; in short he convinced me of his genuine penitence. I believe he has reformed, because he realized he did wrong. You are angry, I know, and I know too that your anger was deserved, but mercy wins most praise when there was just cause for anger.

(Letters 9. 21; cf. 9. 24; trans. Radice)

It seems clear from Philemon 18 that Onesimus had caused some damage to Philemon.73 It must have been rather serious, because Onesimus recognized the need for not just any advocate but one with considerable influence over his master. Although a pagan (Philem. 10), he was aware that Paul had ultimate authority over the new religious group to which his owner belonged. Hence, instead of seeking out a friend of Philemon in Colossae, he went looking for Paul.

In this scenario, which does much fuller justice to the tone and content of Philemon than the hypothesis that Onesimus was a runaway, the episode must have taken place at a time when the sense of Paul’s invisible presence in the church of Colossae was strong, because he was known to be in the vicinity (cf. Col. 2: 5). This was true only when he resided in Ephesus. By the time of Paul’s imprisonment in Rome he had been out of contact with the churches of Asia for several years, and it is doubtful that they even knew where he was. Moreover, in the situation envisaged, time was of the essence. The problem had to be solved before the momentary anger of Philemon became permanent bitterness. The delay of a long journey to Rome would have made the effort of Onesimus pointless. Ephesus was at the limit of the feasible.

Only in the hypothesis of an Ephesian imprisonment does Paul’s plan to visit Colossae, which was concretized in a request for lodgings to be prepared for him (Philem. 22), become intelligible. Nothing is more natural than his desire to follow up in person the impact of his letter on communities, which had been disturbed by false teaching of Jewish origin. The churches of the Lycus valley were not quite halfway between Ephesus and Galatia. If they had exhibited a partiality for Jewish-inspired doctrine might they not fall victims to the Judaizers, whom he had had to combat in Galatia? When in Rome, on the contrary, Paul’s attention was focused not on the east but on the west, not on Asia but on Spain (Rom. 15: 24).

The slender clues in Philemon unambiguously point to Ephesus as its place of origin. In consequence, Colossians must have been written from the same prison. Attempts have been made to find confirmation from within the letter, but the results are unconvincing. Bowen, for example, argues that the fourteen direct allusions to the conversion of the Colossians suggests that the church had been in existence only a matter of weeks or of months at most.74 However, one finds the same sort of allusion to the beginning of their Christian lives when Paul is speaking to the Galatians (3: 2–3; 4: 8–9), and those churches had been founded at least six years previously.

At least two of the three letters combined to create Philippians—Letter A (4: 10–20) and Letter B (1: 1 to 3: 1 and 4: 2–9)75—speak in favour of Ephesus as their place of origin.76 As the seat of the proconsul, the city had a praetorium (1: 13). The great imperial estates in Asia demanded the presence of members of Caesar’s household (4: 22), whose sojourn at Ephesus is confirmed by inscriptions.77 The frequent contacts between Philippi and Paul’s place of imprisonment suggest that the latter was somewhere much closer than Rome.78

Finally, as soon as he got his freedom Paul planned to visit Philippi (1: 26; 2: 24). Not only is this the opposite of what he tells us his plans were after Rome (Rom. 15: 24), but it can only be the visit projected in 1 Cor. 16: 5–9, which was written from Ephesus. Philippians 1: 26 and 30 give the impression that this visit will be the first since the foundation of the church at Philippi (contrast the language of Gal. 4: 13; 2 Cor. 12: 14; 13: 1), but by the time Paul got to Rome he had already visited Philippi at least twice (2 Cor. 1: 16; 2: 13).

Although not entirely free from ambiguity, the hints contained in Colossians, Philemon, and Philippians have a cumulative force. The case for Ephesus as the prison from which they were written is much stronger than one which could be developed in favour of Rome.

Roman law at this period contained no provision for a prison sentence; detention was not used as a punishment. Individuals were removed from circulation for longer or shorter periods through being sent into exile.79 They were held under restraint in two situations, either while under investigation80 or after the death sentence had been passed and they were awaiting execution.81 Other punishments (e.g. scourging, fines) were carried out immediately. In practice, of course, detention could drag on interminably.

These theoretical possibilities of the application of Roman justice are perfectly illustrated by the Acts of the Apostles, which (without assuming the historicity of details) reflects very accurately the realities of the legal situation in the provinces. Once the magistrates accepted the charges laid against the missionaries, Paul and his companions were punished without delay; they were beaten and tossed into jail for the night before being expelled from the city (Acts 16: 19–35). While awaiting judgement on accusations made against him Paul was held first in Jerusalem (Acts 21: 33 to 23: 22), then in the praetorium of Caesarea (Acts 23: 23 to 26: 32), and finally in Rome (Acts 28: 16). Peter was incarcerated while awaiting execution (Acts 12: 1–19). Access to the outside world was dependent on the whim of the official (Acts 24: 22).

There is no hint in any of the captivity letters that Paul is awaiting execution. On the contrary, he expresses his hope of being released in the near future (Phil. 2: 24; Philem. 22). We should assume, therefore, that he was being held while under investigation. If Paul offered public lectures in the hall of Tyrannus (Acts 19: 9), someone may have tried to curry favour with the authorities by drawing attention to a new religious group, which might possibly be subversive. To arrest the leader and his agents in outlying areas pending an investigation would appear a prudent decision to any administrator (cf. John 19: 12).

Before attempting to establish a chronology for Paul’s stay in Ephesus, an important question must be answered: does Galatians have to be taken into account? In other words, was Galatians written during Paul’s stay in Ephesus?

The one clue to the date of the epistle provided by the letter itself is Galatians 2: 5 which, as we have seen, fixes a lower limit of AD 51; the letter was written after the Jerusalem Conference. The upper limit is furnished by the composition of Romans in Corinth during the winter of AD 55–56,82 because there is general acceptance of Lightfoot’s conclusion,

The Epistle to the Galatians stands in relation to the Roman letter, as the rough model to the finished statue. … The matter, which in the one epistle [Gal.] is personal and fragmentary, elicited by the needs of an individual church, is in the other generalised and arranged so as to form a comprehensive and systematic treatise.83

The success of his attempt to establish the priority of Galatians with respect to Romans led Lightfoot to use the same type of comparative terminological and thematic study to date Galatians after 1 and 2 Corinthians.84 His brief treatment, however, is more impressionistic than convincing.85 This fault was remedied by U. Borse, whose exhaustive application of the same methodology refined Lightfoot’s conclusion by dating Galatians between 2 Corinthians 1–9 and 2 Corinthians 10–13, and thus he assigned Macedonia as its place of origin.86 The strength of Borse’s approach is that he uses only contacts that are unique to Galatians and the document with which he is comparing it. Its weakness is illustrated by his treatment of the formula ‘another gospel’ (Gal. 1: 6; 2 Cor. 11: 4). The style and construction of its context in 2 Corinthians, according to Borse, is more developed than that in Galatians; hence in this respect Galatians is more primitive, and therefore earlier, than 2 Corinthians 10–13.87

The underlying principle—the later is always better—is manifestly false, and the aesthetic value judgement intrinsic to the method is always debatable.88 Moreover, there is a subtle, but unjustified, shift from priority to proximity. Borse takes it for granted that thematic and verbal agreements are always time-related, when it is much more probable in this instance that they are subject-related. The contacts he highlights reveal only that whenever Paul dealt with the same problem he tended to express himself in a similar way. It is not at all surprising that Borse finds the greatest number of contacts between Galatians and 2 Corinthians 10–13 because in these two documents Paul is not only dealing with the same issue, namely the inroads into his communities made by Judaizers, but he does so in precisely the same bitterly disappointed frame of mind. Inevitably the same words and ideas surge to his lips.

Once the hypothesis of the proximity of Galatians to 2 Corinthians and Romans is seen to be without foundation, the opening words of the letter can be read naturally, ‘I am astonished that you are so quickly deserting him who called you in the grace of Christ’ (Gal. 1: 6). There is no justification for watering down the normal sense of ‘quickly’ (cf. 2 Thess. 2: 2; Phil. 2: 19, 24) by assuming that Paul has in mind the interval since the Galatians first became Christians. He is astounded that their resistance to the intruders was so shortlived. The brevity of the time factor is uppermost in his mind; it is not as if the endurance of the Galatians had been tested by a long period of hostile pressure. Manifestly he is contrasting previous information concerning the happy situation in Galatia with what he has now been informed is the sorry state of the community.89 When and how did he learn that the Galatians ‘were running well’ (Gal. 5: 7)?

Borse, in order to maintain his Macedonian dating of Galatians, attempts to argue that 1 Corinthians 16: 1 implies that at the end of his stay in Ephesus Paul still had a good opinion of the Galatians.90 One might agree if Paul had praised the generosity of the latter and held them up as an example. But all he in fact says is that the same administrative directive regarding the collection for the poor of Jerusalem, which he now gives the Corinthians, he had given previously to the Galatians. In any case, if the Galatians had agreed to Paul’s request, he could be quite sure that they would be even more responsive to their new guides, the Judaizers, who viewed the Jerusalem church much more favourably than Paul did.

There is in fact no alternative to the only substantiated hypothesis, namely, that Paul learned of the situation of the Galatian churches when he passed through that region, and preached the collection for Jerusalem, en route to Ephesus, a journey which I have dated to the spring and summer of AD 52. It is not impossible that the Judaizers followed closely on the heels of Paul when he left Antioch, and so reached Galatia not long after he had left. If we further assume that their impact was immediate, and that Paul was warned as soon as possible, Galatians could have been dispatched before the snows closed the high country in the autumn of AD 52.

It may be doubted, however, that events moved quite so quickly, particularly since it is a question of a number of churches in Galatia. It is more reasonable to assume that the Judaizers spent the winter in Galatia, and that news of their depredations reached Paul in Ephesus only after the snows had melted and the roads were again open to traffic. We can be sure that Paul responded immediately; the use of the present participles ‘who are disturbing you and who are desiring to pervert the gospel of Christ’ (Gal. 1: 7) indicate that the troublemakers are still at work as he writes, and have not entirely succeeded (cf. Gal. 5: 10).91 Hence Galatians should be dated in the spring of AD 53.

In working out the chronology of Paul’s life, I argued that he arrived in Ephesus in August AD 52 and departed definitively in October 54.92 How Paul spent the summer of AD 54 can be deduced without difficulty from 1 and 2 Corinthians. It has been touched on above and will be considered in some detail when dealing with the Corinthian correspondence. Thus the time-frame with which we are concerned is not quite two years, the twenty-two months from August 52 to May 54. The previous discussion in this chapter gave some idea of his activities during this period. The challenge now is to arrange those activities in at least a relative chronological order.

Paul’s first year in Ephesus, it would appear, was trouble free. After having informed his churches in Macedonia and in Achaia where he could be reached, he was able to devote his energies to the development of the local community and to its missionary outreach into the hinterland.

The period of Paul’s imprisonment must fall between the composition of Galatians, which gives no hint that Paul is a prisoner, and the writing of 1 Corinthians in May AD 54, when he is free to plan a journey through Macedonia to Corinth (1 Cor. 16: 5).

This period is further limited by two factors. Communications between Asia and Greece would have been cut from the end of the sailing season in October to the following April, and Paul is unlikely to have ventured into the interior of Anatolia in the depths of winter. If he planned to ‘winter’ in Corinth (1 Cor. 16: 6), it is improbable that he left Ephesus in winter. As we shall see when dealing with the Corinthian letters, all of Paul’s attention in the spring and summer of AD 54 was concentrated on Corinth.

In consequence, the movements implied in Philippians, and the sending of two of its component letters, must have taken place between the spring of AD 53 and the autumn of that same year. Rather more latitude can be allowed for connections with the Lycus valley. Strong motivation and unseasonably good travel conditions would have made it feasible for Epaphras and Onesimus to get to Ephesus even in winter, and for Paul to travel to Colossae.

Let us look first at Paul’s relations with Philippi. Since the prevailing wind was from the northern quadrant, one would expect travellers from Philippi to Ephesus to come all the way by boat, and Acts provides figures which are eminently plausible: Philippi to Troas five days (20: 6); Troas to Ephesus four days (20: 13–16). In total, therefore, nine days, which could be extended or diminished depending on weather conditions, and on how much time the boat spent in harbour each day. Returning home it was more sensible to travel by road to Troas, in order to avoid the delays imposed by contrary winds. Those who took ship could advance only when the wind swung briefly into the south. Troas was 350 km. (210 miles) from Ephesus, a walk of two weeks at an average of 25 km. (15 miles) per day. From there it was imperative to take a boat. Under optimum conditions the crossing to Neapolis took two days (Acts 16: 11), and the better part of another day was needed to cover the 15 km. (9 miles) from Neapolis to Philippi. The round trip could be done in twenty-six days. In order to allow time for a visit on arrival, however, a month would be a more reasonable minimum estimate.

If we assume that Galatians was written in April or May AD 53, the subsequent events of that summer with respect to Philippi can be reconstructed as follows. The church there sent Epaphroditus with gifts for Paul (Phil. 4: 18). While in Ephesus he fell ill (Phil. 2: 26), which meant that Paul had to find another messenger to carry a letter expressing his gratitude to Philippi (Letter A: Phil. 4: 10–20). Naturally this emissary explained what had happened to Epaphroditus, and brought back to Ephesus the news of the concern of the Philippian community for the invalid (Phil. 2: 26). It is not at all certain that Paul was under arrest at this stage. There is no necessary connection between financial aid from Philippi and imprisonment; the Philippians had previously helped him financially at Thessalonica (Phil. 4: 16), and at Corinth (2 Cor. 11: 9), when he was certainly free. At least two months should be allowed for these contacts, which brings us to July AD 53.

This date suggests the possibility that Paul’s arrest was due to the zeal of the new proconsul of Asia (Phil. 1: 13). This official, who was appointed for one year, took up his duties on 1 July,93 and may have wanted to appear decisive and energetic, when warned of a potentially subversive group. How long his investigation of the nascent church lasted we can never know, but it was not more than nine months and perhaps considerably shorter. Paul and the others may have been released before the end of the summer. The limitations on winter travel make it improbable that Letter B to Philippi (1: 1 to 3: 1 and 4: 2–9), Colossians, and Philemon were written after October. If Paul was released in late summer or early autumn, he could have made his promised visit to the Lycus valley. Whether he spent the winter there, or returned to Ephesus, remains an open question.

According to Acts 19: 1, Apollos had left Ephesus for Corinth prior to Paul’s arrival in Ephesus. This is partially confirmed by Paul’s witness that Apollos had succeeded him at Corinth (1 Cor. 3: 6), and it is unlikely to have been invented by Luke, because it is precisely the sort of the uncontrolled expansion that Luke wanted to correct and control. Apollos had certainly moved back to Ephesus prior to the writing of 1 Corinthians in May AD 54, because he is with Paul at that moment. Since the letter brought by the Corinthian delegation in the late spring of that year requested that Apollos return to Corinth with them (1 Cor. 16: 12),94 the latter must have been in Ephesus since the previous summer. It is most economical to suppose that he brought the information which prompted Paul to write the now lost ‘Previous Letter’ (1 Cor. 5: 9).

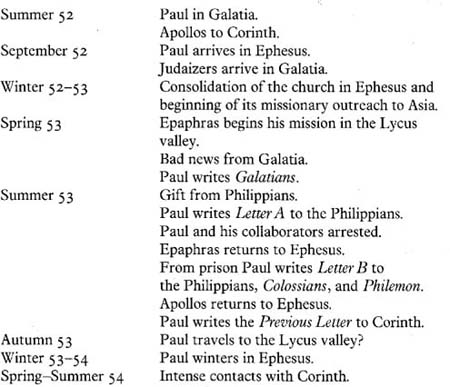

In broad outline, therefore, Paul’s schedule subsequent to his departure from Antioch in the spring of AD 52 was as follows: