Chapter Two

The Great War

There was nothing great about the Great War.

Over 4 years the armies of the Entente – France, Britain, Russia – and the Alliance – Germany, Austria, Turkey – waged war, killing nearly 10 million combat troops. Nearly 7 million civilians died in the fighting or from starvation and disease because of the destruction. Another 5 million died in a mass influenza epidemic just after the war, so that the total lives lost is around 20 million. Around 23 million troops were wounded in the war, many disabled for the rest of their lives. As men were killed in the trenches and detention camps they left their mothers and fathers, widows and orphans, family and friends bereaved. Most of the men in the armies of the Entente and the Alliance did not want to fight. They were dragooned into the ranks, by conscription, under threat of imprisonment or execution; or they were bullied into volunteering. Some chose to sign up, but many of those regretted that choice later on – if they were lucky.

The course of the war

The two main theatres of war were the Western Front and the Eastern Front.

The Western Front was formed with the ‘Battle of the Frontiers’ – many battles in which Germany overran Belgian, and then French towns in August 1914, including battles at Lorraine, the Ardennes, Charleroi and Mons – in the Battle of the Frontiers casualties were 329,000 French, 25,597 British, 4500 Belgians. German casualties were 215,594.

The Battle of the Marne was the turning point of the Battle of the Frontiers: an army of just over 1 million mostly French troops stopped the advancing German army of nearly 1.5 million. France’s casualties (wounded and dead) were 85,000 and German casualties 67,700. Britain had a smaller force in the battle and suffered 1701 casualties.

The Battle of Ypres ran from 19 October to 22 November. German and Entente forces fought over the Belgian city at the cost of 145,000 Entente casualties and 47,000 German casualties (though other operations in Belgian cost many more German casualties).

The Battle of Verdun went on from 21 February to 18 December 1916. In the hills over the French city of Verdun, Germany and France fought an inconclusive battle for control that lasted nearly a year – ‘a lengthy period of general insanity’, Field Marshall Lord Allenby called it. Germany’s army was 1.25 million, of whom 350,000 became casualties (143,000 of whom were killed). France’s army was 100,000 fewer, and their casualties were 400,000 (of whom 159,000 were killed).

The Somme offensive was launched on 1 July and ran till 18 November 1916. A joint British-French force (with the support of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa) attacked German positions on the River Somme. Planned before the German attack at Verdun it was supposed to be a general assault that would push the Central Powers back – but on the eve of the battle Chief Intelligence Officer Brigadier John Charteris admitted, ‘we do not expect any great advance’, and, ‘we are fighting primarily to wear down the German armies and nation’.1

At the end of the day on 1 July, in the Battle of the Somme, British forces suffered 60,000 casualties – 20,000 were killed outright. The 36th (Ulster) Division had suffered over 4900 casualties: 86 officers and 1983 other ranks killed or missing; 102 officers and 2626 other ranks wounded. On the same day the Accrington Pals, 700 strong, were sent into combat for the first time: 238 were killed immediately and 350 wounded. ‘The powers that be are getting a little uneasy with regard to the situation,’ wrote Sir William Robertson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, as the battle ground on: ‘the casualties are mounting up and ministers are wondering whether we are likely to get a proper return for them’.2 The Somme was the largest battle of the war and cost more than 1 million wounded or dead: 420,000 British casualties, 200,000 French casualties and around 470,000 German casualties.

Nivelle Offensive, 16 April-9 May 1917, was based on an ambitious plan to ‘break through’ the German line. French casualties were 118,000-187,000, and British 160,000; Germany suffered 163,000 casualties. The high cost of the attack led to mutinies in the French Army, and Nivelle’s replacement by Petain.

Messines Ridge, 7-14 June 1917: A British Empire force of 216,000 attacked a force of 126,000 in German positions at Messines-Wytschaete Ridge, which they re-took after setting off 21 tons of explosives dug under the enemy trenches. The explosion was so great that it was heard in Dublin. The Empire forces suffered casualties of 24,562 and the Germans 25,000 – 10,000 in the explosion.

Looking over the 45-metre crater left by the Messines explosion

Passchendaele, July to November 1917: The battle was fought for control of the ridges south and east of the Belgian city of Ypres between a British Empire force, with support from some French and Belgian Divisions, and a large German army. Estimates of casualties are contested, varying from 200,000-450,000 Entente troops and 200,000-400,000 German troops. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George called it ‘one of the greatest disasters of the war’ and said that ‘no soldier of any intelligence now defends this senseless campaign’. Commander Hubert Gough was blamed for going ahead before the American Expeditionary Force had arrived.

To understand what these millions of lives lost were worth, look at a map and see where the towns of Ypres, Messines and Passchendaele are. Today it would take you half an hour to drive through all three. Another 3 hours would take you down to Verdun in northern France. The Western Front barely moved more than a mile either way for the greater part of the war.

Meanwhile, on the Eastern Front

Where the Western Front was, by the winter of 1914, fixed, the Eastern Front was endlessly churned up. The Austrian Army was not well led, but German forces cut through Russia’s plans and territory. Total losses for the spring and summer of 1915 amounted to 1,400,000 killed or wounded, while 976,000 had been taken prisoner. On 5 August, with the Russian Army in retreat, Warsaw fell. According to one engineer:

It is hopeless to fight with the Germans, for we are in no condition to do anything; even the new methods of fighting become the causes of our failure.

General Ruszky agreed:

The present-day demands of military technique are beyond us. At any rate we can’t keep up with the Germans. (August 1914)

In July 1915 the ministers chanted:

Poor Russia! Even her army, which in past ages filled the world with the thunder of its victories...Even her army turns out to consist only of cowards and deserters.3

In answer to alarmed questions from his colleagues as to the situation at the front, the War Minister, Polivanov, answered in these words: ‘I place my trust in the impenetrable spaces, impassable mud, and the mercy of Saint Nicholas Mirlikisky, Protector of Holy Russia.’ (Session of 4 August 1915).

The Russian Army lost in the whole war more men than any army which ever participated in a national war – approximately 2.5 million killed, or 40 per cent of all the losses of the Entente. According to Aleksandr Pireiko:

Everyone, to the last man, was interested in nothing but peace...Who should win and what kind of peace it would be, that was of small interest to the army. It wanted peace at any cost, for it was weary of war.

Minister of the Interior Nikolay Maklakov feared that the soldiers on leave in Moscow were trouble:

That’s a wild crowd of libertines knowing no discipline, rough-housing, getting into fights with the police (not long ago a policeman was killed by the soldiers), rescuing arrested men, etc. Undoubtedly, in case of disorders this entire horde will take the side of the mob.

Russia’s defeats and its own inner turmoil meant that by 1917 it was struggling to keep up the fight, and in October of that year it withdrew altogether.

The final battles on the Western Front

The Spring Offensive, 21 March to August 1918: Following the Russian treaty at Brest-Litovsk settling the war in the east, Germany put all its major forces into the Western Front, in an effort to break the deadlock. The push was also known as the Spring Offensive and the ‘Kaiser’s War’, or ‘Kaiserschlacht’. German advances into Entente positions were extensive but made at great cost.

There were 688,341 German casualties, 418,374 British and 433,000 French losses. By its end the German predominance on the Western Front was at an end, through its own losses and by the arrival of the American Expeditionary Force. In Germany the Kaiser’s War was seen as a last throw of the dice.

The Hundred Days Offensive, 8 August to 11 November 1918. With the arrival of US troops in the summer of 1918 the balance of power shifted to the Entente, the battles that followed saw Germany pushed back out of Belgium and France. The Battle of the Argonne Forest was a major part of the final Allied offensive of the First World War that stretched along the entire Western Front. It was fought from 26 September 1918 until the Armistice of 11 November 1918, a total of 47 days. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive was the largest in US military history, involving 1.2 million American soldiers. The battle cost 28,000 German lives, 26,277 American lives and an unknown number of French lives.

That autumn, the German Army was defeated – but not by the troops of the Entente or the United States of America.

A World War

The Western Front and the Eastern Front were not the only theatres of War. Britain backed Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, in his revolt against Ottoman rule, with the forces of the British-Indian Army. The war cost the lives of tens of thousands of Turkish troops, and also plunged Syria, the Lebanon and Palestine into famine.

People were found in the streets, unconscious, and were carried to hospitals. We passed women and children lying by the roadside with closed eyes and ghastly, pale faces. It was a common thing to find people searching the garbage heaps for orange peel, old bones, or other refuse and eating them greedily when found. Everywhere women could be seen seeking eatable weeds among the grass along the roads.

It was estimated that between 60,000 and 80,000 had died of starvation in northern Syria.4

In Africa Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck led a force of European and native troops from German East Africa in a prolonged guerrilla war against British and Portuguese colonial forces. The greatest loss of life was among the native bearers – the ‘carrier corps’ that both Lettow-Vorbeck and the British were dependent upon.

They waged war against their own men

The conditions of war were onerous and brutalising. On the Western Front men fought from trenches that were often flooded. The bodies of their comrades were often rotting nearby, lost in ‘no-man’s land’. They were plagued by rats, flies and lice.

All around me the most gruesome devastation. Dead and wounded soldiers, dead and dying animals, horse cadavers, burnt out houses, shell-cratered fields, devastated vehicles, weapons, fragments of uniforms – all this is scattered around me, in total confusion.

Most of all the filth ground men down.

My sacks dangled in the water, the contents became sodden and a tremendous weight. My overcoat (thick) did the same. My upper half became plastered with mud, with constantly slipping against the side of the narrow trench. My rifle, wrapped in sandbags became the same…

German infantryman Paul Hub5

Men in the army were brutalised and dominated by violent and autocratic commanding officers. The military is not a democracy. It runs on orders. Basic training was all about breaking men’s spirits and getting them to obey orders without question.

They began to flog soldiers for the most trivial offences; for example, for a few hours’ absence without leave. And sometimes they flogged them in order to rouse their fighting spirit.

Aleksandr Pireiko

The first clue about the bond between the men and the officers was that the men in the trenches were armed with rifles, the officers with small arms. The officers had pistols to shoot men who would not advance.

The second clue about the bond between the men and the officers was the great many desertions, and later mutinies that wracked the armies of the Entente and the Alliance. Around 100,000 British and German troops called an unofficial ceasefire on Christmas Eve 1914, to the anger of their commanding officers (and again on Christmas Eve 1915). In Singapore, in 1915, the Muslim Rajput soldiers of the 5th Light Infantry, angered by constant discrimination, mutinied, killing their officers and taking control of the territory. The Russian Army was beset by desertions as troops abandoned the line in their thousands, and in February of 1917 their protests triggered a revolution in Russia – its key demand was an end to the brutalisation of troops by their commanding officers, and also for an end to the war.

The Grumble, Leon Henri Ruffé’s engraving of French troops after the Nivelle offensive

In April 1917, after the failure of the ‘Nivelle Offensive’, and having heard of the Russian mutinies, thousands of French troops mutinied refusing orders to fight – they elected leaders and called for an end to the war. Twenty-seven thousand deserted. Around a thousand men mutinied in the British training ground at Etaples, the ‘Bull Ring’, in September 1917. In October 1917 the Russian Army again mutinied and again this was part of a larger revolution that took the country out of the war altogether. In the autumn of 1918 the German Navy at Kiel began a mutiny that turned into a revolution, effectively bringing the whole war to an end. Troops deserted and mutinied because they had been pushed to the point of endurance and beyond, and often they turned their bayonets on their commanding officers.

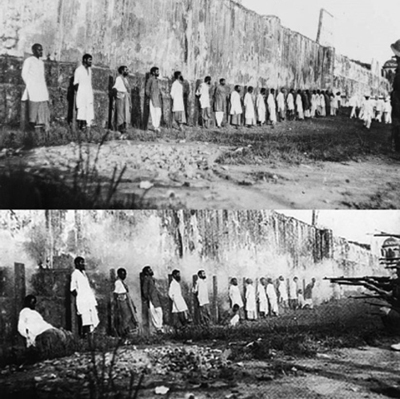

Execution of the Fifth Light Infantry at Singapore

The third clue as to the bond between the officers and the troops is that thousands of men were shot at the orders of their officers for not fighting, either for ‘cowardice in the face of the enemy’, desertion or mutiny. British court martials had 306 soldiers shot at dawn, of whom 266 were convicted of desertion and 18 of cowardice. Among them were 25 Canadians, 22 Irishmen, 5 New Zealanders and 21 of the Chinese labour corps. French officers executed 600 men for desertion, cowardice in the face of the enemy and other offences. Of the mutineers of the British-Indian Army in Singapore in 1915, 47 were killed by firing squad and a further 64 exiled for life. The German Army records just 18 executed.

‘Total War’

Germany’s military leader Erich von Ludendorff called the Great War a Total War. He meant that not just the soldiers, but everyone had to do their part, that all society would give to the war effort. That was true. Before the soldiers could be sent over the top into no-man’s land all the nations’ collective efforts had been mobilised in civilian life as they were in military life.

The war cost lives, and it cost money.

| Dead | |

| British Empire | 947,000 |

| French Empire | 1,400,000 |

| Germany | 1,800,000 |

| Austria-Hungary | 1,200,000 |

| Russia | 1,700,000 |

| USA | 116,000 |

| Italy | 65,000 |

Not only were lives lost to those countries, but the billions spent on the war were wasted too. The cost of the entire war was estimated at £80 billion (five and a half trillion in 2018 sterling) – or enough to give ‘every family in America, Canada, Australia, Great Britain and Ireland, France, Belgium, Germany and Russia’, estimated Dr Nicholas Butler of the Carnegie Foundation, ‘a five-hundred pound house, two hundred pounds worth of furniture, and a hundred pounds worth of land’.6 A lot of government spending was borrowed money, debts which after the war would sap the European recovery and cause more conflict over who would pay the bills. All that government spending, even if it was on credit, still had a terrible impact on society before the debts were repaid. Every penny spent on munitions and guns commanded resources that otherwise would have been going towards really useful things, like cutlery, bicycles and bread. War spending soaked up all of society’s good endeavours and put them instead to waste and destruction. Factories making engines and tools were turned to making bombs and barbed wire. People who were farming the land were sent off to fight. A massive shift took place from producing things that would help people, like food and other consumer goods, and also tools and machines, to working at making things that would kill people.

The amount of food and other necessaries of life was cut right back. Though war industries put more people to work, meaning that more people had a wage packet at the end of the week, the shift from making goods to making weapons meant that all those wage packets were chasing fewer and fewer consumer goods. That mean that inflation shot up, making basics so expensive that people could not afford them; the extra cash in their pockets was worth less. From July 1914 to July 1916, wrote labour economist Maurice Dobb, the official cost of living index rose 45 per cent, where wage rates had only risen some 15 to 20 per cent. In Glasgow, where workers flooded into new munitions factories, no new dwellings were built, so that rents went up.

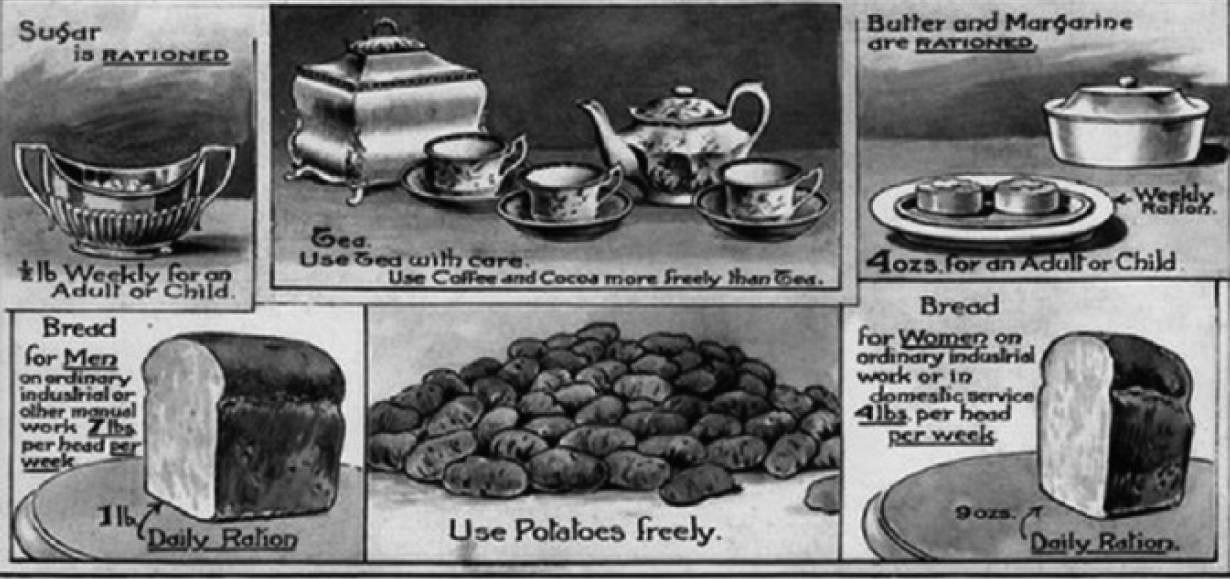

In Germany ration cards were introduced in February 1915: first bread was rationed (1.5 kg) followed by potatoes (2.5 kg), 80 grams of butter, 250 grams of sugar and half an egg a week: about a third of the calories a person needs. The next winter all food was in short supply, so that it became known as the ‘Turnip Winter’. In Russia baking white bread was forbidden as provision trains failed to reach Moscow and other cities. Rationing came later in Britain, with 2lb of meat, ½ lb of sugar and ½ lb of total fats allowed each a week.7

British rations explained

Either through inflation or rationing, consumption was held down, while more people were working in the munitions factories. Propaganda campaigns urged women to help the war effort by reusing their scraps. Local authorities, like Croydon, organised workers’ kitchens to save money on food. ‘Real wages in Britain fell sharply,’ explains historian Adrian Gregory, ‘whilst production actually rose.’8

One and a half million Indians were recruited into the British-Indian Army, no longer available for farming, and the country was taxed with feeding that army as well as occupied Mesopotamia. In 1918 the strain was too much, prices skyrocketed and people were starving. Viscount Chelmsford wrote to the Secretary of State for India that, ‘stocks of all food grain will barely suffice to meet internal demand’. In some Turkish villages only 15 per cent of those of military age returned and if it were not for the hundreds of thousands of deserters, farm output would have collapsed altogether.9

Industrial conscription

There was industrial conscription as well as military conscription. ‘We can hardly win a war without the industrial workers,’ Undersecretary of State Wahnschaffe wrote to Ludendorff. In February 1915 the ‘Committee on Production’ was set up in Britain under the Chairmanship of Sir George Askwith, with the aim of finding out how ‘after consultation with the representatives of employers and employed as to the best steps to be taken to ensure that the productive power of the employees in engineering and shipbuilding establishments…shall be made fully available to meet the needs of the nation in the present emergency’.10

British unions and the government signed a deal at the Treasury outlawing strikes; so did the German unions, on 2 August 1914. Under Britain’s War Munitions Act of 1915 munition workers were forbidden from leaving work without the permission of the Ministry of Munitions (or the Admiralty, which managed many of the factories and workshops). Under the 1915 act it was illegal in a ‘Controlled Establishment’ for anyone to ‘restrict output’. The Ministry of Munitions issued employers with ‘certificates of exemption’ meaning that workers in vital industries could not be conscripted into the army, which meant that they could not leave their work, either.

The Commissioner of the Committee of Inquiry into the Causes of Industrial Unrest found that ‘the nerves of the men and their families are raked by hard workshop conditions, low and unfair wages in some cases, deficient housing accommodation, war sorrows and bereavements, excessive prices of food’. He added that ‘the authorities were ignoring their grievances and troubles and threatening them instead with Military Service’.11

In Germany, on 2 December 1916 the German government brought in the Hilfsdiengesetz – or law of mobilisation – which ‘tied the worker to his workplace’. Every man between 17 and 60 not already in the armed forces was made to report to the authorities with a certificate of employment or a certificate from a previous employer. In that latter case he would be directed to a place of work. If he refused, or left his work, he could be imprisoned for a year.12

The workforce changed in make-up, too. Between 1914 and 1918, hundreds of British factories were re-tooled to make munitions. Over 890,000 women – teenagers, wives, mothers and grandmothers – joined the 2 million already working in factories. Trade union membership climbed from 6.5 million to 8 million. They filled the gaps left by volunteer and later conscripted servicemen.

In Germany, the BASF chemical factory had 900 Russian and Polish prisoners of war among its 22,000 strong workforce. When the prisoners acted up, they brought in a ‘supervising officer’ who, in the words of the internal company records, ‘introduced a strict regimen’.13

Coercion was common in war industries. When miners at West Cumberland Ore went on strike the government issued an order that those who carry out ‘any act calculated or likely to restrict the production’ of war material ‘are guilty of an offence under the Defence of the Realm Regulations, the punishment for which is penal servitude for life’. As labour activist William Paul argued, ‘every nation at present is in reality waging two wars – the national war abroad and the class war at home’.14

With their rights to leave work taken away, employees were exposed to exploitative and dangerous conditions. One worker in a small arms factory, Cook, died suddenly, and at the inquest it was found he had been working 80 hours a week. The coroner said that he ‘died for his country’. ‘There were cases of men working 100 hours a week,’ according to labour economist Maurice Dobb, ‘and 70 to 80 hours were not uncommon,’ while 56 to 60 hours a week was the norm.15

The feeling that the work had to be done to protect the men in the trenches was a powerful reason to cut corners when it came to safety. In his memoirs Lloyd George highlighted the case of the women working in munitions who often suffered ‘toxic jaundice from TNT poisoning’: ‘The ailment turned their faces a repulsive yellow’ – earning them the nickname of canaries. In 1916 there were 181 cases of TNT poisoning, 53 of which were fatal; 189 cases and 44 deaths in 1917; 34 cases and 10 deaths in 1918. In a factory at Hayes women were put to work hammering defective American shells; ‘risky work’, said Lloyd George, ‘for if a trace of the fulminate were ignited by the blow’, the shell ‘would explode and disembowel them’.16

Thirty-five women were killed in an explosion in 42 Shed, at the Barnbow munitions factory in Leeds, at 10pm on Tuesday 5 December 1916. The National Shell Filling Factory in Chilwell, Nottinghamshire was destroyed in an explosion of 8 tons of TNT on 1 July 1918. In all 134 people were killed, of whom only 32 could be positively identified, and a further 250 were injured. A total of 109 were men, 25 women. Factory manager Lord Chetwynd blamed it on sabotage, but more likely it was the poor safety standards that were to blame.

The Brunner Mond munitions factory in Silvertown exploded on 19 January 1917 – though the news of the extent of the losses was suppressed: on the memorial in the Silvertown Works, just the 16 people in the shed that exploded are listed as dead; Hector Bolitho’s biography of Alfred Mond published in 1933 says 40 were killed. Today it is acknowledged that 73 people were killed as the blast tore through the surrounding houses, of which around eight hundred were destroyed. Brunner Mond were compensated £185,000 for their loss of earnings by the UK Government.17

The African Carrier Corps were forced to work under the British Empire’s Native Followers Recruitment Ordinance

Forced labour was more naked in the treatment of colonial and foreign workers. Britain and France recruited Chinese labourers under an agreement with Finance Minister Liang Shiyi to supply 300,000. The men were contracted under indentures that lasted for 5 years. Once they had signed on they were under military discipline as the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC), and imprisoned in barracks, working 10 hours a day, 7 days a week. The work was dangerous – 752 were killed when their ship, the Athos, was hit by a German torpedo, and news of their deaths was suppressed at the time. Researcher Chen Ta for the US Bureau of Labor Statistics listed 25 riots and strikes by CLC workers between November 1916 and July 1917. Of the 140,000 labourers sent to France, 10,000 died. Twenty-one of them were executed for mutiny.18

In Africa ‘the British had in 1915 passed the Native Followers Recruitment Ordinance, a law that allowed for compulsory recruitment of men from across British ruled Africa to work as carriers’. By the end of 1917 more men in the British colonies that bordered German East Africa had served as carriers than had not. Around 250,000 men died servicing the British war effort in Africa, and another 120,000 died as carriers to Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck’s East Africa force. They died from exhaustion, infected wounds and other diseases, weakened by malnutrition. They were slaves.19

‘Prussianism’

Democracy, which was in any case limited, was largely suspended throughout the war. Governments of national unity avoided elections or any open debate about war aims. Laws were passed to silence opponents of the war, like the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) in Britain and the Military Service (No. 2) Act. Under DORA the offices of both the moderate peace campaign, the Union for Democratic Control, and the more radical No-Conscription Fellowship were raided in 1916. The laws demanded that all leaflets and papers carried the names of the publisher and author, so that they could be prosecuted.

In 1904 the British Army had set up a press bureau to monitor the newspapers, and in January 1916 ‘the press bureau had been re-established as bureau M17a (censorship) responsible to the Director of Military Intelligence, General McDonogh’. M17b, meanwhile, was hived off to work with the Foreign Office, producing foreign propaganda.20

Anti-conscription posters, the Guildford chief constable was advised, were to be torn down or defaced. Those posting them, his South Shield counterpart was instructed, should be advised that their actions would appear to contravene DRR 27, a catch-all regulation dealing with the expression of views prejudicial to the conduct of the war, and should be stopped. If necessary, legal actions were to be taken against such persons.21

Suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst, Glasgow socialists John McLean, Willie Gallacher and John William Muir, liberal philosopher Bertrand Russell were all detained under DORA. Many more less well-known activists faced prison, too, as Brock Millman explained: ‘Oxford undergraduate Alan Kaye was sentenced to 2 months’ imprisonment in 1916 for distributing “Shall Britons Be Conscripts?”’ ‘Clara Cole and Rosa Hobhouse’, who had organised a peace pilgrimage, ‘were arrested and sentenced to 5 months’ imprisonment’. R. V. Cox, another No-Conscription Fellowship member, was tried for selling their paper The Tribunal. No publisher would touch The Tribunal after the press bureau threatened them, so it was run off on a roneo machine.22 The No-Conscription Fellowship’s Fenner Brockway was arrested four times and spent most of the latter war years in Walton prison, while chairman Clifford Allen was arrested three times, his health collapsing in 1917. Meetings organised by the No-Conscription Fellowship were regularly banned, or the venue owners rung by the police and persuaded to cancel the meeting.

In Germany in the autumn of 1914, authorities banned meetings of anti-war socialists in Stuttgart, Munchen-Gladbag, Liepzig and Altona. Radical newspapers like the Rheinische Zeitung, the Volksblatt and the Echo vom Rheinfall were ordered to close. The Social Democratic paper Vorwarts was closed in September and only allowed to reopen the following month when the editors promised not to mention the ‘class struggle’.23 Leading socialists were imprisoned, including Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Ernest Meyer and Franz Mehring. Despite being an elected deputy in the Reichstag, Liebknecht was sentenced to four-and-a-half years in prison.

Before the war, Britain, Germany and France were democracies – with some pointed restrictions. But for the duration, they became dictatorships that silenced dissent with jail time, suspended Parliamentary debate, censored the Press and seized suspect literature.

Fighting back

Two years before the Great War started, the socialist parties of Europe met in Basel. There they agreed to oppose war between their states – a policy they had first set out in 1907 – and even to call a general strike to prevent the war. But on 4 August 1914 both the German and the French socialists in their respective parliaments voted in favour of war budgets. The Socialist International was shattered by the war, as the brotherhood of man gave way to German, French, British and Austrian socialists turning their guns against each other.

Many socialists, like Keir Hardie, Ramsay MacDonald and Jean Jaures were opposed to the war. Some, like Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, John McLean and V. I. Lenin were set to make a revolution against it. But the majority of the socialist leaders, men like Arthur Henderson in Britain (whose sons were in the army), railwaymen’s leader Jimmy Thomas and even the firebrand Victor Grayson backed the war; so did Belgian socialist Emile Vandervelde and Sweden’s Hjalmar Branting, and Pierre Renaudel of France. Years of lobbying their own domestic governments for reforms led these men to embrace patriotism.

In the summer and autumn of 1914 those few hold outs who were against the war were isolated, and on the defensive. But such was the strain that war placed on the whole of society, that in time the anti-war activists were speaking to large crowds of angry men and women. Over the next 3 years there were more and more protests and strikes over different features of life under war time. The war put tremendous stress on society, curbing wages, demanding more labour, threatening famine and wasting lives. All that stress provoked protests and revolts. Many of these conflicts were not in the first place protests against the war. But even where they were not, governments tended to cast them as if they were. Strikers were told that they were siding with the enemy. Protestors were put under martial law. Reacting against war time conditions, more and more people began to protest against the war itself – at which point governments lost control.

In 1915, 200,000 Welsh miners went out on strike against the Munitions Act, which they thought was dictatorship. The strike was remarkable in that it was wholly political, against the war measure, not provoked by any change in their day-to-day terms and conditions. That year Mary Barbour and Andrew MacBride organised a great rent strike in Glasgow. The rent strike led to the formation of the Clyde Workers Committee, which gathered shop stewards in the engineering plants and docks. The Clyde Workers Committee launched a number of strikes over pay and working conditions. When Munitions Minister David Lloyd George went to Glasgow to talk to the strikers, he was booed in a great public hall (nine days later, Scottish socialists John Maclean and James Maxton were jailed in revenge).

Assistant Secretary to the Cabinet William Ormsby-Gore fulminated that ‘the essence of this movement is, of course, the new form of Marxian syndicalism, revolutionary in its aims and methods, aiming at the overthrow of the existing social and economic order by direct action’. Ormsby-Gore warned that:

the leaders, whether Jew or Irish, have this common feature, they are all men with dissatisfied national aspirations, embittered against society and bent on using the results of the war to overthrow the existing order of things.24

The Times editorialised: ‘We must deal as harshly with strikers who throw down their tools as with soldiers who desert in the field.’25

On 28 May 1915 more than a thousand women demonstrated for peace in front of the Reichstag. That November women demonstrated in Stuttgart against the high cost of living, while police in Liepzig were called out to put down food riots. In Berlin there were protests and fighting outside of empty shops in February 1916. Then in May the small Internationale group of socialists called a demonstration against the ‘imperialist war’. Karl Liebknecht published a popular leaflet with the headline, ‘the main enemy is at home’ – meaning that it was the bosses that were the true enemies of the German workers, not the French and British soldiers in the trenches. Thousands rallied around Liebknecht at the Potsdamer Platz. When he was arrested, 55,000 Berlin munitions workers, led by Richard Müller, came out on strike.26

On the front line, German soldiers wrote back home, but their letters were intercepted by the censors: they called for peace, said that the war was a capitalist war, and that ‘at home they must strike and strike hard, and cause a revolution, and then peace must come’.27

The most audacious blow against the war recruitment drive was struck in Ireland in Easter 1916. There the moderate Irish nationalist leader John Redmond had pledged the Irish Volunteers to the British war drive in the hope of winning Home Rule when peace came. Soon it became clear that the Irish recruits in the British Army would still be second-class citizens to their British officers (many of whom were Ulster loyalists with a special hatred for Irish Catholics). After the losses in Gallipoli and with a steady depletion of Irish men, the feeling that they were cannon fodder in a British imperial war became stronger. A group within the volunteers opposed the war and organised themselves independently. Their leaders – Patrick Pearse, Tom Clarke, Seán MacDermott, Joseph Plunkett, Éamonn Ceannt and Thomas MacDonagh, along with James Connolly’s Irish Citizens Army – launched a pre-emptive rebellion in Ireland seizing the Post Office in Dublin to announce a republic. For a week the Irish rebels fought to hold Dublin, while the might of the British Empire turned away from the Western Front to try to take back what had been a part of the United Kingdom just a month earlier. The suppression of the rebellion cost thousands of lives, and demolished central Dublin. But the execution of the leaders of the Rising only strengthened hostility to Britain, so that much of the country was in open opposition to the war, to conscription and to the continuation of British rule. The Socialist International’s hope for a general strike against the war in Europe was disappointed in 1914, but in April of 1918 Irish workers, with the support of Sinn Fein, did organise such a strike. That, along with the Anti-Conscription Protests, stopped the application of conscription in Ireland throughout the war, while it went ahead on the British mainland.

In February 1917 a women’s day protest in St Petersburg quickly escalated into an all-out general strike across the city. Textile and munitions workers joined to paralyse the city. They protested against the Tsar, against the war and against its hardships. Soldiers back from the front joined the protests. A panicked Tsar ordered the fearsome Cossack troops to clear the protests, but even those hardened reactionaries would not charge the women in the streets. The Tsar’s power ebbed but he resisted calls to abdicate until it was clear that he was no longer in charge anyway. No ruling power existed apart from the workers’ councils – ‘soviets’ – that the protestors gathered in. Without much confidence the liberal politicians who had cowered under the Tsar before called themselves a Provisional Democratic Government, under the leadership of the moderate socialist Kerensky. To win the confidence of the French and British ambassadors, Kerensky promised to keep up Russia’s part in the war, but it was a promise that would prove fatal to his government.

Over the summer the provisional government struggled to keep the initiative. Though they called themselves democrats, they avoided calling elections, for fear that they would be thrown out. By the autumn local election results gave majorities instead to the anti-war ‘Bolsheviks’. The ‘soviets’ that the workers and soldiers set up to represent their interests did not give way to the new provisional government but carried on, creating a ‘dual power’ between the masses’ and the middle classes’ rival governing institutions.

Kerensky called on the military to suppress the Bolsheviks, only to panic when it became clear that General Kornilov planned to overthrow him, too. To stop Kornilov the soviets created a Military Revolutionary Committee tasked with defending the February Revolution. Kerensky never did call an election to give his provisional government a mandate. When an All-Russian Soviet Congress was planned Kerensky again tried to use the military to stop it. Kerensky’s Foreign Minister Pavel Milyukov said:

The bourgeois republic, defended only by socialists of moderate tendencies, finding no longer any support in the masses...could not maintain itself. Its whole essence had evaporated. There remained only an external shell.

The fate of the Kerensky government was necessarily the same as that of the tsarist monarchy: ‘Both prepared the ground for a revolution, and on the day of revolution neither could find a single defender.’ The Military Revolutionary Committee overthrew Kerensky and supported a Soviet Government, led by the Bolsheviks.28

In January 1918 the Austrian government cut flour rations, and the workers at the Daimler factory in Wiener Neustadt walked out. The strike snow-balled, with 200,000 out on 17 January and by 19 January Vienna workers were joined by miners in Ostrau, Brno, Pilsen, Prague and Steiermark. In Budapest, a general strike paralysed the city. The Viennese authorities quickly gave in. The strikers’ success inspired Berlin, where 400,000 went on strike on 28 January. They were followed by strikes in Dusseldorf, Kiel, Hamburg and Cologne, with around 4 million out in total. The protests were only stopped when the German government declared a ‘state of siege’, rounding up the ringleaders to try them in courts martial. One hundred and fifty were imprisoned and nearly 50,000 sent into the army and packed off to the Western Front.29

All of these actions can be seen as if they were merely reactions to social conditions, just spontaneous or mechanical reactions. But in truth all of these protests were made by people who, in different ways, decided they had had enough. Those people were not acting in a vacuum. They could see – or read about – what was happening in the rest of the world. The French mutinies after the Nivelle offensive failed were self-consciously modelled on the February Revolution in Russia, even to the point of organising ‘soldiers councils’ to argue their case. The workers’ strikes in Germany were inspired by the Russian October Revolution. The Russian revolutionists were watching the revolts in Budapest and Germany, hoping that these would give them more support. The anti-war leaders in Britain, John Maclean and Sylvia Pankhurst, campaigned for the new Soviet Union against its enemies and were rewarded with positions as ambassadors of the New Society.

How the war really ended

Russia’s February Revolution gave Germany’s military leaders hope, but it also inspired opponents of the war. The ‘German proletariat must draw the lessons of the Russian Revolution and take their own destiny in hand’, said Fritz Heckert of the far-left Spartacist group. The Minister of the Interior bemoaned ‘the intoxicating effect of the Russian Revolution’.30

On the cruiser Friedrich der Grosse, a stoker, Willy Sachse, and a sailor, Max Reichpietsch, started a discussion group of socialists. On shore at Wilhelmshaven they talked to other ships crews and other canteen committees were set up making a secret League of Soldiers and Sailors.

Reichpietsch went to the Socialist Party headquarters for help but was told that it was against their policy to recruit in the armed forces. ‘We ought to stand in shame before these sailors,’ party organiser Luise Zietz said, ‘they are much more advanced than we are.’

The ‘Flottenzentrale’ – a secret committee to coordinate 5000 sailors was set up on 25 July 1917. Their slogan was ‘Arise! Let us break our chains as the Russians have done!’ In August 1917 the ships the Prinz Regent Luitpold and the Pillau were in open revolt. Hundreds of men walked off. The authorities rounded up the ringleaders and Reichpietsch and Alwin Köbis were executed on 5 September. Watching these events in Russia, Lenin saw them as ‘a great turning point’ and ‘the eve of a worldwide revolution’ – words he put into deeds shortly after with the October Revolution.

The Russian revolutionaries had their own challenges, but they were committed internationalists and set about promoting a revolutionary end to the war. Karl Radek, a socialist leader in Poland and in the German SPD before leaving for Russia, became Vice Commissar for Foreign Affairs in the new government. He organised German socialists from among the prisoners of war held by the Russians, who put out a German language journal Die Fackel (‘The Torch’). German soldiers and workers should turn on their own generals and bosses to bring the war to an end was its message.

In Germany the different socialist leaders were generally sceptical – Bernstein and Kautsky (who were often the targets of Lenin’s polemics) rubbished the Russian Revolution, and even Rosa Luxemburg was unsure. But actions spoke louder than words. The Manfred Weiss armaments factory in Budapest was struck out and strikes broke out across Austria-Hungary. German workers were immediately moved by the Bolshevik Revolution. A massive strike wave broke out across Germany in January 1918. ‘Workers’ councils’ were set up in Vienna and Berlin. A Spartacist leaflet lauded ‘the workers councils of Vienna elected on the Russian model’ and announced a general strike beginning on 28 January. Five hundred thousand were on strike in Berlin, led by activists like metalworkers’ leader Richard Müller. The trams were shut down. The socialist leaders condemned the action. Ebert told the crowd at Treptow Park: ‘it is the duty of the workers to support their brothers and their fathers who are at the front and to make the best possible weapons for them’. Just to emphasise the point he added, ‘as the English and French workers are doing for their brothers at the front’. The strikers were left high and dry by the socialists they thought would lead them and they drifted back to work. Between March and November 1918 nearly 200,000 Germans were killed in the war.

Despite the collapse of the January strikes, the Bolshevik revolution continued to stand as a model of how to end the war for the mass of Germans. Veteran socialist Franz Mehring spoke out in favour of the Bolsheviks saying they were the true inheritors of the socialist tradition. The SPD leadership could not contain what they called ‘the romantic taste for the Bolshevik revolution’. The more radical Spartacist group was making headway in the major cities. The moderate socialists in the Cabinet pressed for the release of Karl Liebknecht, fearing that his imprisonment would become a cause celebre for the growing radical movement. Out of prison he went straight from the Potsdam station to a rally calling for a Russian Revolution in Germany. By October workers were setting up revolutionary councils at the Daimler plant in Stuttgart and the Zeppelin plant in Friedrichschafen. Labour activists Richard Müller and Hugo Haase fixed the date of the Revolution for 11 November.

At Kiel sailors were hearing that they were to ready for a general offensive. On board the ships, they protested, and about a thousand men were arrested and disembarked. On 1 November sailors met at the trade union centre at Kiel, led by Karl Artelt, and called a demonstration for the third. The demonstration was banned, but many went ahead. An armed patrol opened fire and nine people were killed, 29 wounded. That night Artelt set up a ‘sailors council’ on a torpedo boat which rallied some 20,000 on different ships. The officers were overwhelmed and straight away started giving in to the men’s demands – to abolish saluting, for shore leave and so on. Before long Kiel was under the command of the sailors’ council. They appealed for help, and at Wilhelmshaven a workers’ and soldiers’ council, led by the stoker Bernhard Kuhnt, called a general strike. The strikes were supported in Berlin and Hamburg. In a panic the socialist leaders reversed their position and called for the abdication of the Kaiser and an Armistice.

The November Revolution in Germany

The Great War was started by statesmen and generals, thoughtlessly and hysterically defending their honour with the waste of other people’s lives. The war was brought to an end by different people. With sober senses the opponents of the war, in Dublin in Easter 1916, in St Petersburg in February 1917, and again in October 1917 – and in Kiel, Wilhelmshaven and Berlin in November 1918 – organised the mass of the people to stop the war. On 9 November the government announced the Kaiser’s abdication. On 11 November a German delegation signed the Armistice before France’s General Foch. The war was over.