Chapter Four

Remembering the War Dead

Eight and a half million soldiers died in the First World War and for the most part they were buried where they fell. In March 1915 Marshall Joffre had ordered that no bodies could be dug up. Some British soldiers’ bodies were repatriated. But that was on an ad hoc basis without a general rule. In practice that meant that officers whose families had influence were more likely to be repatriated while most were left where they were first buried. One of the last bodies to be brought back was that of Lieutenant William Gladstone, a Member of Parliament since 1911, and the grandson of the former Prime Minister William Gladstone.

In 1916 Sir Fabian Ware got the Adjutant General to ban all further exhumations and repatriations. From then on, the rule was that no bodies were to be brought back, but to be left where they were buried in northern France, Belgium or the other makeshift war graves.

The reason for the ban was explained in different ways. Marshall Joffre said that it was a health hazard. Red Cross leader Sir Fabian Ware was worried that the ad hoc repatriations would show that officers and men were not equal in death. Behind all of these claims was the fact that the British Army, like other armies in the combat, would not commit themselves to a general rule of bringing the bodies back. It was not possible, they thought, because of the logistical commitment, because of the cost, and because the mass repatriation of bodies would undermine morale, in the army and at home.

At the end of the war the British Government faced a dilemma. The grieving families had no body to bury. Their sons had given up their lives to the British Empire, but they would not even have a grave they could tend. Feelings were running high, and the government appointed an Imperial War Graves Commission to manage the problem.

The War Graves Commission decided that the rule that bodies would not be brought back should hold after the war. The commission was ‘aware of a strong desire…that exhumations should be permitted’. But they dismissed that with the argument that ‘it would be contrary to the principle of equality of treatment’, meaning that the ad hoc repatriations would favour the wealthy. In fact most of the bodies were exhumed, but only so that they could be reburied in tidy lines in France and Belgium.1

Though they were painted as selfish rich people, those who wanted their sons brought back were not. Around 90 letters a week landed in the War Graves Commission’s post box asking for repatriation.2 In 1919 the British War Graves Association was formed by Sarah Ann Smith, whose son Frederick was buried in the Grevillers Cemetery at the Somme. The association, which grew to around 15,000 strong, mostly in the north, wanted the return of the war dead to England. William Dawson had visited his son Robert in hospital in France, but when the soldier died of his wounds, William was not allowed to take his son’s body back. Dawson wrote to the War Graves Commission quoting the Versailles Treaty, that said that signatories would offer ‘every facility for giving effect to requests that the bodies of the soldiers and sailors may be transferred to their own country’ – but they did not budge.

Ruth Jervis wrote to the commission asking: ‘is it not enough to have our boys dragged from us and butchered (and not allowed to say ‘nay’) without being deprived of their poor remains?’ In a second letter she protested, ‘the country took him, and the country should bring him back’.3

The one option that the War Graves Commission never looked at was that the army should bring all the bodies back. The costs – financially and to morale – were just too high. The cost of sending the men to the front was a necessary one, but the cost of bringing them back was not to be considered.4 In 1924 Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald wrote an abrupt letter to Sarah Ann Smith of the British War Graves Association saying that it would be impossible to move 800,000 bodies ‘scattered all over the world’.5

As well as barring repatriation, the War Graves Commission decided that all graves should follow a uniform style. This was too much for some of the bereaved, who wanted to put their own headstones on their sons’ graves. In the House of Lords ‘an unexpectedly strong current of opposition’ to the policy was voiced, calling it a ‘gross and wicked tyranny’.6

The Chinese Labour Corps were made to stay on after the war to clear the battlefields

What few people were willing to admit was that a great many of the markers that were in place did not correspond to the bones beneath them. At the end of the war there were to be 580,000 identified and 180,000 unidentified graves, and 530,000 men whose graves were not known. ‘Soldiers returning wounded or on leave to England were complaining bitterly,’ warned Fabian Ware in 1917, ‘about the number of bodies still lying out on the Somme battlefield’. Edward Lutyens, the architect who designed the cemeteries, found the sites in ‘disarray’, ‘a ribbon of isolated graves like a milky way across miles of country, where men were tucked in where they fell’. Among those clearing up the battlefield were the Chinese Labour Corps, under slave-like conditions. Where the graves were gathered in larger groups, Lutyens worried that they were packed so close together that it would be hard ‘to arrange their names in decent order’. (Lutyens liked an orderly display and he took great pride in laying the graves out in endless rows, as if the bodies were still on parade.)7

The 250,000 Africans who lost their lives in the service of the British Army were treated even worse. The British governor of Tanganyika territory told the War Graves Commission that he ‘considered that the vast Carrier Corps Cemeteries at Dar es Salaam and elsewhere should be allowed to revert to nature as speedily as possible’.8 There is a generic bronze monument to native forces, including the Carrier Corp, at Mwembe Tiyari in Mombasa, but the war grave at Dar es Salaam lists only 1843 dead, mostly European soldiers and some of the King’s African Rifles. Where there were war memorials put up for non-white troops, as for the Indian Army losses in Mesopotamia, the Nigerian Regiment and the West African Frontier Force, only the officers’ names were engraved in stone.9 An official history of the War Graves Commission regretted that ‘the traditions of the Indian Army… paid great attention to the graves of expatriate Britons but little to those of Indian servicemen’. So it was that ‘by 1924 every British grave had a headstone, but nothing had been done to commemorate the Indians’, and when extra funds were released to set about that ‘it was too little and too late’.10 The Nigerian forces monument put up in 1932 in Lagos did honour the Carrier Corps along with the Hausa Regiment, but it did not carry the names of the African dead of the Great War until 2015, when it was relocated to the new cemetery at Abuja and more than 2000 names from both world wars were added.

The decision not to return the bodies of the dead troops to their grieving families left an emotional hole that had to be filled. Instead of being mourned by their loved ones individually, the dead were to be dragooned into a collective commemoration.

Official commemoration of the dead would take the families’ grief and turn it into a collective worship of the war dead, making them a sacrifice to the God of War – or more prosaically, to King George, General Haig and the other chieftains who had sent the men off to be killed in the first place.

The case against war had been strongly put. The best argument against the war was the cost in lives. What the official commemoration of the dead did was to take all the grief that might have counted against the war-mongers and turn it instead into part of the case for war. The dead were now called the ‘fallen’ (though most had been struck down). The killing was sanctified as a ‘sacrifice’ – the ‘Greatest Sacrifice’. ‘Scarcely a British family was untouched in some way or degree by the war: to hundreds of thousands came the greatest sacrifice of all’, editorialised the Daily Mail on 11 November 1919. They had been sacrificed to the greater glory of the British Empire. At the first official Remembrance Day, Prime Minister David Lloyd George laid a wreath with his own hand-written note: ‘A token of gratitude to those who died that we might live more abundantly’.11 It was true that British industrialists enjoyed a massive increase in profits in the war, and Lloyd George like most British statesmen had investments that paid good dividends. But for most of the ex-soldiers and ordinary men and women of Britain, the years after the war were not ones of abundance, but of more ‘sacrifice’.

Remembrance Day

On the day of the Armistice marking the end of the war, 11 November 1919, most people were just glad it was over. ‘There was no sense of victory, much less any hatred of the enemy,’ recalled Captain Alan Thomas of the 6th Battalion, ‘only a strong desire to get home’. In London and other English towns, the crowds celebrated through the night, but diaries and letters of the time show that many who had lost loved ones were privately grieving while the world cheered. Daisy Davies’ daughter remembered that her mother had borne the death of her husband Charles stoically, and was surprised to find her weeping over the washing on Armistice Day. ‘Well, I have no one to come home and love me,’ her mum explained.12

There were celebrations, but they did not last. Many soldiers were angry that they could not go home straight away. Marooned in demobilisation camps, waiting for trains and ferries, the men rioted. On 3 January 1919 British soldiers who were in Britain on Christmas leave were ordered to return to the continent. When they gathered at Dover and Folkestone, 9000 of them refused to get on the boats. On 4 and 5 March, Canadian soldiers in the Kinmel Camp in Wales broke out. Three of the rioters and two sentries were killed as it was put down, and 21 injured. All told around 50,000 soldiers took part in protests demanding repatriation. Also, as the No-Conscription Fellowship pointed out, ‘1,600 Conscientious Objectors are still in prison’ – many of them for their second year.13 With one eye on the mutinies of German, Russian and French servicemen, the authorities in Britain were fearful. Sir Basil Thompson, the Special Branch Metropolitan Police Commissioner, said that ‘during the first three months of 1919 unrest touched its high watermark’, and, ‘I do not think at any time in history since the Bristol Riots we have been so near to revolution’.

Official ceremonies and parades, and the building of monuments, played an important part in restoring order. The Cenotaph, Edward Lutyens’ monument to the war dead, was first unveiled not at ‘Remembrance Day’ – the anniversary of the Armistice in November – but at a Victory Parade in July – ‘Joy Day’. At the procession, Butcher Haig saluted the bust of Lord Kitchener. ‘The hosts of the dead,’ wrote the Manchester Guardian’s reporter, ‘were commemorated in the simple classical Cenotaph, tall and narrow and white.’ Sir Edward Lutyens’ Cenotaph of July 1919 was a temporary structure, made of plaster and wood, like a Hollywood set piece, that ‘had risen in a day out of Whitehall’.14

On the same day, a different assembly was held in Merthyr Tydfil, where 25,000 gathered to remember the dead, but also to demand higher pensions for ex-servicemen and their dependents. In Luton, ex-servicemen were told they could not hold their own commemoration – so they set fire to the town hall, and when the firemen turned up the soldiers held them back until the building was gutted. Luton was put under martial law for several days. In Chertsey, servicemen boycotted the victory parade, protesting over pensions, as well as the sending of the British Expeditionary Force to Russia, to attack the fledgling Soviet Union.15

James Cox, President, International Union of Ex-Service Men, said:

the whole thing is a mockery, and it is sheer hypocrisy to ask the discharged men to take part in what is officially termed ‘joy day,’ while the widows and dependents of his fallen comrades are housed in hovels and existing in a state of semi-starvation.16

James Cox could see how the armed services were being used to put down protests by working people after the war, like those in Glasgow and Belfast. ‘Just as their army and navy was used to defend their economic interests abroad,’ labour activist William Paul wrote, ‘so now are the armed forces to be used to defend the economic interests of the financiers at home.’17

There were some doubts among traditionalists about the Cenotaph. The Church Times saw ‘a cult’ of ‘Cenotapholotry’ and the Catholic Herald thought it was ‘Pagan’. Lord Alfred Mond thought it was maudlin and defeatist, and wanted it taken down after the Victory Parade. But the government needed to keep its grip on the way that the dead were remembered to make sure that they were not recruited to more radical causes, like proper pensions for ex-servicemen, or worse, against the intervention in Russia. The Cenotaph was kept up for the first anniversary of the Armistice, which was the first Remembrance Day, on 11 November 1919. On the order of the King, ‘there was made a great silence’, reported the Daily Mail:

The King was right. His minutes of silence were golden, with memory and hope and new faith that the torch received ‘from dying hands at Flanders fields’ will be carried on.18

The crowds were large, and French Premier Clemenceau joined Lloyd George at the ceremony. Across the country, reported the Daily Mail, people stopped in silence: ‘mill girls cried when the looms were stopped’; in the Nottingham Assizes Court, ex-soldier Frederick Carter stood for 2 minutes’ silence after the King’s Letter was read to the court – before he was sentenced to death by Mr Justice Greer for killing his landlady.

Once again there were protests of unemployed veterans who had to be kept back, and in Manchester a representative of the Ex-Servicemen’s Association was refused permission to address the procession there on ‘the case for the living, in honour of the dead’. The British War Graves Association held a mass rally calling for repatriation of the bodies the night before. Ex-Servicemen’s leader James Cox wrote that it would have been better to reflect ‘on how the widows and dependents of the fallen are being treated, and to what treatment the maimed and disabled men are being subjected to since their return to civil life’.19

Lutyens’ wood and plaster structure was looking tatty, and the Ministry of Works announced that it would come down in January 1920. But the Daily Mail and other newspapers started up a campaign for a permanent Cenotaph – which was unveiled by King George in November 1920: ‘The Cenotaph, its new Portland stone a pale lemon, rose before us naked and beautiful’, the Manchester Guardian trilled.20

The word ‘Cenotaph’ means an empty coffin or tomb. Sir Edward’s design for the Cenotaph at Whitehall is clearly a coffin, or sarcophagus, set high on a great pedestal that soars above the crowds. In keeping with the Art Deco style, Lutyens’ Cenotaph is spare but with non-classical proportions, many times higher than it is long or broad, like a Charles Rennie Mackintosh chair back. It has no explicit religious symbols (which is what irritated the churches). The inscriptions read, ‘the Glorious Dead’, and ‘1914-1918’. The meaning of Lutyens’ Cenotaph is that the empty coffin stands in for the war dead, who were left on the battlefield. It is a substitute for personal grief, redirected into a public ceremony. This was how the abandonment of the dead in Flanders and northern France was to be justified – with a token tomb in place of a real one.

The Unknown Soldier

To add to the meaning, the unveiling of the new Cenotaph was coupled with the burial of an ‘Unknown Soldier’ in Westminster Cathedral. The idea was that:

The burial of an unknown fighting man among the great men of history with impressive pageantry will express the honour the nation pays to the legions of fighting men who fell, whose sacrifice is commemorated in another way in the Cenotaph.

Like the Cenotaph, the price of fame was anonymity. The soldier would always remain unknown to earn his place among ‘the great men of history’: ‘Whether a soldier or an airman, a man of Great Britain or the Dominions, will never be known.’21 He could be anyone, that is, as long as he was British, or from one of Britain’s white colonies (Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Newfoundland or South Africa – which only sent white troops).

The British Cabinet read a paper that October that said that ‘it would do honour to the great mass of fighting men’. They resolved that ‘the remains of one of the numerous unknown men who fell and were buried in France should be exhumed’ to be reburied in Westminster Abbey, the ‘symbolic exception’ to the rule that no soldier was to be disinterred and repatriated.22

The Unknown Soldier, like the empty sarcophagus in Whitehall, would always remain a lifeless abstraction, while real, living ex-servicemen and the bereaved relatives were left to look on, spectators at their own symbolic interment.

The Cenotaph, as seen by Arthur Wragg for the Peace Pledge Union

‘With honours and devotion passing those given to Kings, the nameless warrior was buried in Westminster Abbey yesterday,’ reported the Manchester Guardian: ‘The body of the unknown, brought in procession from Victoria Station, reached the Cenotaph’ just as the King unveiled it and Big Ben struck 11. The Times editorialised that the Unknown Soldier was ‘the silent ambassador of the legion dead to the courts of the living’, and was ‘an emblem of the “plain man”, of the masses of the people who in every age, have borne their full share of our national wars’. That month the International Federation of Trades Unions took a different view declaring ‘that the fight against militarism and war, and for world peace, based on the fraternisation of the people, is one of the principle tasks of the unions’.23

The poets were sceptical of the official celebrations. Auden wrote:

Let us honour if we can

The vertical man

Though we value none

But the horizontal one.

Siegfried Sassoon imagined one visitor:

The Prince of Darkness to the Cenotaph

Bowed. As he walked away I heard him laugh.

With that, the Remembrance Day commemoration became part of Britain’s official, secular ceremonial.

Later Remembrance Days

On 11 November 1921 the Daily Herald published a poem by George Slocombe, The Phantom Army. Slocombe imagined the ghosts of the Great War marching up Whitehall: ‘An army of dead men, and marching before/Harry of Hackney, Commander-in-Chief.’ ‘Harry whom Hackney will see no more’ marches into Downing Street and sits in the Prime Minister’s seat writing Royal Proclamations on a pad ‘to the poor People of this Here Land’: ‘work for the workless’ and ‘bread for the starving’. When the Prime Minister finds the notepad he pushes it away: ‘The dead are dead, thank God! And they will never come back.’ ‘But woe for him,’ wrote Slocombe, ‘if the dead came back.’

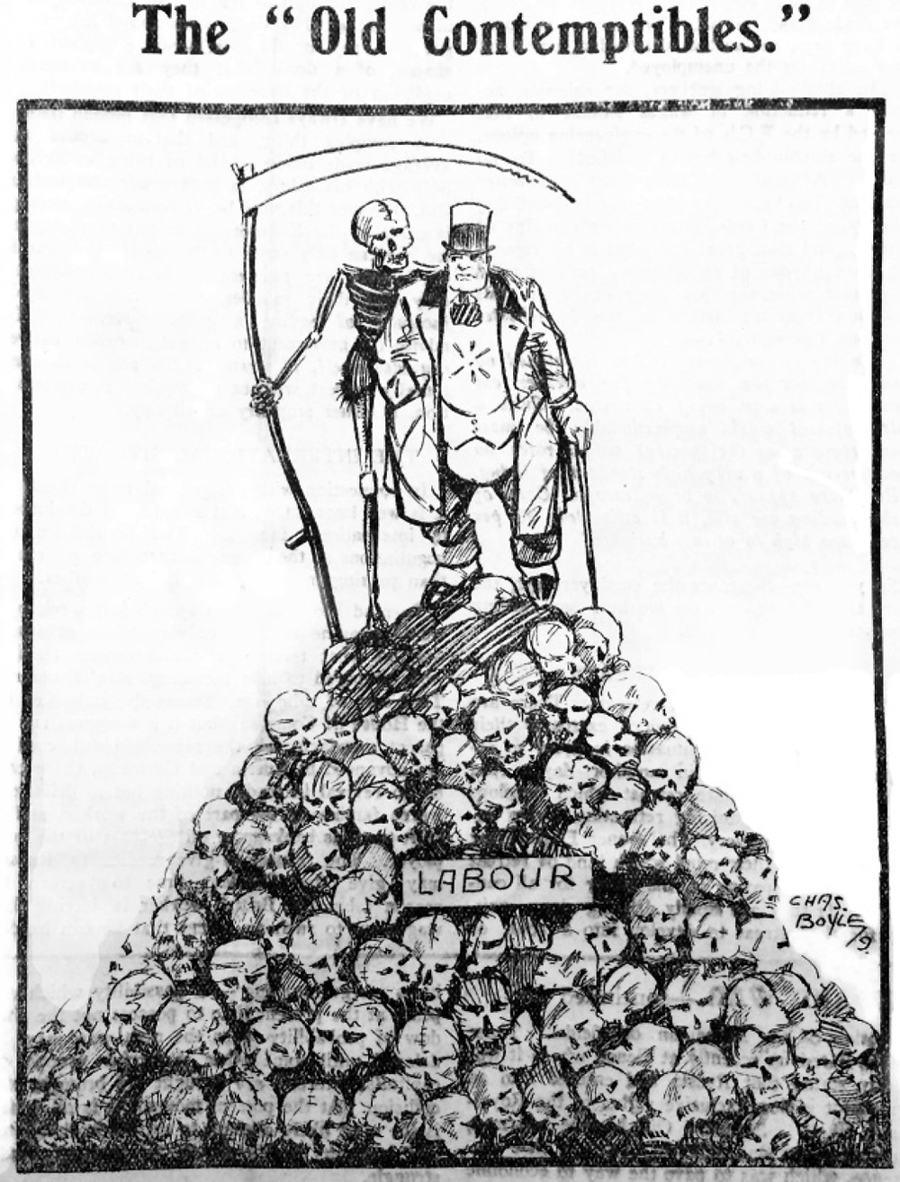

On 11 November 1921 the Clyde Workers’ Committee newspaper, The Worker, led with a cartoon by Chas Boyle, the Old Contemptibles, with death standing alongside a top-hatted capitalist embraced by death at the top of a pile of skulls. Death thanks the capitalist for his ‘magnificent achievements in my service’. The capitalist replies ‘pooh! A mere bagatelle to what I am going to do the next war for freedom.’

Alongside the cartoon, The Worker carried a poem by the radical politician Henry Labouchere, as an antidote to the imperial propaganda of the Remembrance Day Parade:

Where is the flag of England?

Seek the land where the natives rot.

And decay and assured extinction

Must soon be the people’s lot.

Go to the once fair islands

Where disease and death are rife,

And the greed of a callous commerce

Now battens on human life.

Where is the flag of England?

Go sail where rich galleons come

With their shoddy and loaded cotton,

And beer and Bibles and rum.

Seek the land where brute force hath triumphed

And hypocrisy hath its lair,

And your question will thus be answered —

For the flag of England is there.

In the lead up to the Remembrance Day parade The Worker reported that ‘throughout the length and breadth of Britain great demonstrations are being organised to declare – Never Again!’

Disillusioned and weary, disgusted and fed up with the aftermath of the Imperialist bloodbath of 1914-18, the masses are rising to declare, ‘There shall be no imperialist wars.’24

The Worker was focused on the British actions against Turkey. Under the headline ‘War! What For?’ they warned that ‘the Imperialists of Britain are preparing another massacre of the working class’, and ‘their kept Press is commencing to beat the War Drum’. British claims to stand for ‘the Freedom of the Seas’ was ‘a joke in the mouths of representatives of the power which controls the sea-trade routes throughout the world’. The Worker was sharply critical of the war-mongers’ claim that the action was called so ‘that the gains of the late war shall not be lost’.

The late war had no gains for the workers. The heroes who fought in it are all at the starvation level now, whether employed or unemployed. The unemployed serviceman is batoned ruthlessly should he try to manifest his independence. The disabled ex-serviceman is kicked from pillar to post.25

There was precious little reason to put faith in the peace negotiations to limit arms. Listen to Field Marshall Sir William Robertson, cautioned The Worker:

We should disregard all pious aspirations and shams regarding international agreement for limiting or prohibiting aerial warfare. Agreement or no agreement, when a nation has its back to the wall, it will, and ought to, use every means for bursting its adversary.26

In September 1923 the National Peace Council organised 70 demonstrations all over the country under the ‘No More War’ slogan.27 That November The Worker headlined ‘Watch War-Mongers Hypocrisy on Armistice Day’. ‘Their name liveth for evermore’, wondered The Worker, or ‘should it be “forgotten already”?’

The fifth anniversary of the world war finds the Capitalist States of the world reeling through poverty and famine towards a fresh imperialist massacre.28

Enemies of war in 1923 were horrified by the punitive reparations that the allies had imposed upon defeated Germany. The National Peace Council warned that ‘the fate not only of millions of our fellow human beings but the future peace of the world becomes more precarious every day’.29

‘I have never seen anything so dreadful in all my experience,’ Ruth Fry of the Friends War Victims’ Relief Committee told the Manchester Guardian after visiting the Ruhr:

No one has any coal. Hot meals are an impossibility. The people are living on bread and margarine.30

In 1924 the National Peace Council again held demonstrations on the ‘No More War’ theme, this time in 152 cities and towns, and followed those up with a national ‘No More War’ conference. Two thousand turned up for a meeting at the Holborn Empire. The National Peace Council also held an Emergency Meeting on the Egyptian Crisis at Essex Hall, on 2 December, after British officers massacred villagers. Philip Snowden argued that ‘a dreadful murder had been committed, a crime which should not be condoned by partial silence’. Other speakers were George Lansbury and Captain Wedgwood Benn.31

In 1928, in Parliament anti-war MPs challenged the government’s commitment to disarmament. Labour MP Rennie Smith asked the Secretary of State for Air about the air display at Hendon: ‘Is the Minister going to have a display of the bombing of a native village, as was the case last year?’

Samuel Hoare said that there would be a set piece but ‘the bombing will not be of a native village’. ‘Will it be a civilised village this year?’ asked Lt-Commander Kenworthy. At that MPs suggested ‘a replica of the House of Commons’, ‘with dummy Minister’. In the programme for the 1930 Hendon Air Display the ‘native tribesmen’ were re-named ‘international outlaws’, but the meaning, as the National Peace Council pointed out, was the same: the Royal Air Force had perfected the aerial bombardment of ‘native villages’ in Iraq between 1920 and 1924.32

Since there was a Labour government in power, peace protestors hoped that they could get them to turn away from war. Dr Alfred Salter asked Labour War Minister Tom Shaw if the Armistice Day could be turned into a peace and memorial service:

Impossible! Unthinkable! It would be opposed by the highest authorities!.

Why! We get more recruits for the Army in the fortnight following the Armistice ceremony than in any other time of year!33

In 1931 the peace movement was having an impact on the establishment’s ownership of Great War Remembrance. Nearly six thousand people went to a rally on Armistice Eve at the Albert Hall, with George Lansbury and Richard Sheppard speaking on No More War. The Women’s International League’s disarmament petition had 1.5 million signatures.34

In 1937 campaigners argued that ‘Armistice Day can be used for peace’. The official celebrations were ‘to make use of it, by association, to strengthen the war convention’: ‘There will be the poppies with their sentimental association with picturesque battlefields, instead of the reality of war.’ The ‘innumerable memorials up and down the country’ suggest ‘that heroes laid down their lives, instead of got the death they were giving others’. The peace activists were planning an outdoor meeting with the MP Isaac Foot, the novelist Storm Jameson and Canon Dick Sheppard in Regent’s Park on Armistice Day.35 Meanwhile other campaigners were planning ‘a substitution for, or counteraction of, the red poppy’ by selling white poppies, to raise money for War Resisters’ International, and for conscientious objectors in prison all over the world.

‘Year by year a greater proportion of the nation becomes tired of the military preparations held in regard to the so-called “War to end war”,’ said the General Secretary of the Women’s Cooperative Guild, calling on all to wear the white poppy. The Peace Pledge Union’s supporters planned to tackle sellers of the Haig Fund’s red poppies ‘to challenge the seller as to what she is doing to prevent war’.

They took risks, arguing with the Haig Fund’s red poppy sellers. Two clerks were sacked from their jobs for wearing the white poppy to work, told that it was ‘an absolute insult to the company’.36

When Remembrance Day was cancelled

In 1937 an editorial in Peace News asked, ‘what if a greater tragedy should occur? Would that obliterate this celebration?’ A Canadian veteran made a similar point that ‘another war would make a mockery of the solemn remembrance of the dead’.37

Artist E. E. Briscoe imagined a bombed Cenotaph in Peace News in 1937

Two years later, Europe was once again at war. What happened to Remembrance Day then?

In 1939 the government announced that, ‘The ceremony at the Cenotaph will not be held as there is a danger that the sound of the sirens may be thought to be warning of an air raid.’ In Peace News John Barclay wrote, ‘the grim irony of this bald official statement needs no comment’.38

10 November 1940 was the ‘Strangest Day of Remembrance’ according to the Daily Mail. At St Paul’s ‘two thousand people usually attend this service’, but ‘yesterday there were only 80’.

Armistice Sunday usually sees a great throng of sightseers and pilgrims...But yesterday they only came in small groups, singly, in couples...ex-Service men and women, all of them wearing a badge of service in the present struggle.

Four middle aged men placed a large wreath of Flanders’ Poppies at the foot of the monument...Occasionally there were passers-by...

The following year, the Bishop of Chelmsford wrote:

Today is Armistice Day. There will be no official observance and no organised ceremonial. But these things are not indispensable: we can each keep our Two-Minutes Silence in our own way and we shall do.

The bishop promised that the parents of the dead ‘will flush with pride as they greet their hero children in the Great Beyond’.39

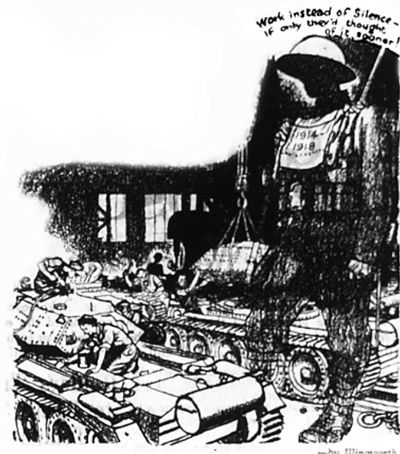

The Daily Mail, the paper that campaigned to have a permanent Cenotaph, carried a cartoon by Illingworth, applauding the decision to abandon the Remembrance Day parade and the two minutes’ silence.

‘No nation-wide silence stilled Britain yesterday – the 23rd anniversary of the 1918 Armistice,’ reported the Daily Mail on 12 November 1941: ‘Arms factories, dockers, shipbuilders, miners carried on the drive for final victory.’

Illingworth’s cartoon for the Daily Mail

Not everyone had got the government memo that grief was suspended for the duration: ‘many gathered at the Cenotaph in Whitehall to pay private homage as traffic rattling by dulled the tones of Big Ben striking eleven’.

Women, carrying shopping bags, hurried between traffic streams to lay their humble tributes.

The meaning of Remembrance Sunday was that it squared the circle, connecting the grief and unhappiness of the war with the case for the military. Grief was repackaged as ‘sacrifice’. Militarism was dressed up as ‘honouring the dead’. The great upsurge of anger at the human cost of the war was acknowledged by those that sent the men to their deaths, then it was twisted and turned until it could be redirected into a solemn adoration of the God of War.

Anzac Day

Australia and New Zealand have their own commemoration day, ‘Anzac Day’, for the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, on 25 April. The date is that of the opening of the Battle of Gallipoli, when 65,000 ‘Anzacs’ joined the Entente force that took on the Ottoman troops under Mustafa Kemal. Eight thousand, seven hundred and nine Australians were killed at Gallipoli and 2721 New Zealanders. The first commemoration of Anzac Day was the following year, 1916, in many towns in Australia and New Zealand. Since 1920 Anzac Day has been an official holiday in New Zealand, and since 1921 in Australia, to commemorate the 60,000 Australians and 18,000 New Zealanders who were killed in the war.

But while Australians and New Zealanders remembered the sacrifice of their young men, the commemoration was intermingled with bitterness towards Britain and the Entente war-mongers.

The main flaw in the Gallipoli landing was that it left the troops stuck on a narrow beach, below a great cliff, from which Mustafa Kemal’s forces could bombard them at will. Churchill – as so often – was carried away with the idea of a coup de grace that would hand him the war in a single stroke. It was a piece of magical thinking brought on by the intractability of the Western Front, but it turned out to be a terrible human sacrifice to Churchill’s folly. Admiral John Fisher wrote to Churchill warning him that his plan would lead to disaster: ‘you are bent on forcing the Dardanelles and nothing will turn you from it – nothing’.40 Worse still, Churchill made sure that Fisher’s doubts were kept from the Cabinet. In 1917 the Dardanelles Royal Commission reported that the First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill, was ‘carried away’ by ‘his sanguine temperament and his firm belief in the success of the undertaking which he advocated’.

The 1917 report condemned Lord Kitchener, too, finding that he was unable to delegate, leading to ‘confusion and want of efficiency’, that because of him there was no meeting of the War Council between 19 March and 14 May 1915, and that Kitchener ‘held back additional troops for three weeks without telling Churchill’. Peace activist Len Fox, who wrote a pamphlet The Truth About ANZAC in 1937, concluded that ‘these were the two men who led the Anzacs to their death – an over-imaginative politician and an under-imaginative general, who blundered on as their fancy dictated, without and even against the advice of experts, and even of each other’.41

Faces of the men of the Anzac as they approached the shore

The misery of the men pinned on the beach was made worse by the military’s failure to supply them with water so that ‘several men went raving mad with thirst’. More, ‘the provision for the evacuation of the wounded’, admitted the commission, ‘proved insufficient’.42 On 11 March 1926 Labour MP Hugh Dalton pointed out that the Turkish Army was firing on the men below the cliff with armaments supplied by the British firm Vickers. He asked the House of Commons:

Did it matter to the directors of these armament firms, so long as they did business and expanded the defence expenditure of Turkey, that their weapons mashed into a bloody pulp all the morning glory that was the flower of Anzac, the youth of Australia and New Zealand, yes, and the youth of our own country?

Anzac Day was important to Australia and New Zealand’s ruling elites. But for the ordinary people it always had a different meaning, since it stood for the way that they had been treated as cannon fodder by the Westminster government. The radical historian James Rawling wrote in 1937: ‘Anzac Day commemorates one of the foulest crimes that has ever been committed against the working class of this country’, and yet ‘thousands still surround the day with dreams of glory and accolades of honour’. Still, Rawling was confident that ‘once the masses of Australia understand fully the horror of that crime at Anzac, the obscenity of the offering to God Capital, then their indignation will be so much greater for all the bombast and talk of glory that surround its celebrations’.43

Rawling was prophetic. In the 1970s and 1980s, anti-war and feminist protestors took their cause to the Anzac Day Parade. So scandalised was the Australian Government that anyone should be off-script that they decided to ‘make it an offence for persons to disrupt an Anzac Day Parade or an observance or ceremony at or near the Australian War Memorial’.44 In 1981 peace protestor Lyn Lenox was prosecuted, but the jury would not convict.