Chapter Six

A Century of British Militarism

It was the ‘war to end all wars’ – but what was Britain’s record of keeping the peace since 11 November 1918?

When the war against the Central Powers was over, the British Army launched a number of military operations across the world.

Who were the targets of those actions?

First and foremost it was those countries who had been allies of Britain during the war of 1914-18 that were subject to military intervention in the years that followed. In the period 1919-23 the British Army waged war against the following countries: Russia, in the ‘War of Intervention’; India, in a series of policing operations; Ireland, the former British colony that declared its independence in 1916, and reaffirmed it in 1919; Iraq, the Arab nation that had sided with Britain and the Entente to fight against the Ottoman Empire in the ‘Arab Revolt’; and Egypt, Britain’s ‘veiled protectorate’. A report in the The Worker for 6 September 1919 pointed out that ‘at the time of writing the British troops on the various war fronts amount to over 300,000.’ They broke that down as follows:

North Russia 20,000 or more, Siberia 1400, Black Sea and Caucasus 44,000, Egypt and Palestine 96,000, Mesopotamia 21,000, India, 62,000, Ireland 60,000, besides at least 100,000 guarding German prisoners in France.

Each one of these allies and former allies was subject to the most punitive attacks, immediately after the Great War was concluded. In each case the demands of fighting a war alongside Britain, or under British command, had raised expectations of just rewards only for them to be dashed, provoking such a reaction that the Court of St James felt it necessary to crush those rebellious former allies. The wars and policing operations that Britain fought in the immediate aftermath of the Great War visited terrible hardship on those very peoples who had been rallied to support the Entente in their fight against the Central Powers.

British intervention in Russia

British general F. C. Poole landed at Archangel on 1 August 1918. Britain’s excuse was that since the Russians had left the war under the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that March, up to 70 German divisions were free to be moved to the Western Front. Quickly it became clear that the British were not there to fight the Germans at all, but to fight the Russians. Straight away Major-General Poole ‘believed that he could effectively act on initiative with impunity’ and saw himself from the start ‘as a viceroy ruling over a dependant people’. Poole saw the North Russian Government under the Social Revolutionary Nicholas Chaikovsky as ‘a purely administrative authority and preferred to deal with Commander Chaplin of the pre-revolutionary Russian Navy and his followers’. With Poole’s connivance, Chaplin overthrew Chaikovsky’s civilian administration, and Poole’s forces pushed 300 miles south of Murmansk. The Bolsheviks halted the allied advance around 150 miles inland on the river Dwina by the railway link to Volodga. On 10 August, the War Office told Poole to ‘take the field side by side with the [White Russian] Allies for the recovery of their country’.

The war was undeclared and savage. Corporal V. F. King remembered:

When you got into a village you had to clear the village out as soon as you ever came across any men. They weren’t Bolsheviks. They were loyal Russians they used to tell you but as soon as your back was turned they were Bolsheviks again.1

‘We used gas shells on the Bolsheviki,’ Ralph Albertson, a YMCA official who was in North Russia in 1919, wrote in his book, Fighting Without a War:

We fixed all the booby traps we could think of when we evacuated villages. Once we shot more than thirty prisoners… And when we caught the Commissar of Borok, a sergeant tells me he left his body in the street, stripped, with sixteen bayonet wounds. We surprised Borok, and the Commissar, a civilian, did not have time to arm himself…I have heard an officer tell his men repeatedly to take no prisoners, to kill them even if they came in unarmed…I saw a disarmed Bolshevik prisoner, who was making no trouble of any kind, shot down in cold blood…Night after night the firing squad took out its batches of victims.

General Poole had to explain himself in a leaflet: ‘We are not fighting Russia or honest Russians,’ he wrote. ‘We are fighting Bolsheviks, who are the worst form of criminals.’2

By the early part of 1919 the British forces in Archangel and Murmansk numbered 18,400. Fighting side by side with them were 5100 Americans, 1800 Frenchmen, 1200 Italians, 1000 Serbs and approximately 20,000 White Russians.3

Lieut.-Colonel Sherwood-Kelly, VC, back in England from commanding a battalion of the Hampshire Regiment in North Russia, wrote to a newspaper that:

the troops of the Relief Force which we were told had been sent out purely for defensive purposes were being used for offensive purposes on a large scale, and far in the interior, in furtherance of some ambitious plan of campaign, the nature of which we were not allowed to know...

Worse, ‘the much-vaunted “loyal Russian Army”, composed largely of Bolshevik prisoners dressed in khaki, was utterly unreliable, always disposed to mutiny, and...constituted a greater danger to our troops than the Bolshevik armies opposed to them’. Sherwood-Kelly concluded, perceptively, that ‘the puppet Government set up by us in Archangel rested on no basis of public confidence and support and would fall to pieces the moment the protection of British bayonets was withdrawn’.4

In the east the anti-Bolshevik General Kolchak at Omsk in the Urals was being supplied by Britain on the advice of British General Alfred Knox: ‘Between October 1918 and October 1919, Britain sent to Omsk 97,000 tons of supplies, including 600,000 rifles, 6,831, machine guns, and over 200,000 uniforms.’ He also had two British Army battalions.5

Britain also supplied General Denikin’s forces in the south sending:

full British army kit for half a million men, 1,200 field guns with almost two million rounds of ammunition, 6,100 machine guns, 200,000 rifles with 500 million rounds of ammunition, 629 lorries and motorcars, 279 motorcycles, 74 tanks, six armoured cars, 200 aircraft, twelve 500-bed hospitals, 25 field hospitals and a vast amount of signal and engineer equipment.6

The post-war government in Britain was fearful that the public would find out that they were fighting a war against Bolshevik Russia and kept up the charade that they were only providing support. Still, ‘the officers of the Royal Tank Corps started to act as tactical commanders of Denikin’s armoured corps also to take part in fighting as vehicle commanders and crewmembers’. Major Bruce’s tank detachment’s role in taking Tsaritsyn was used as a model in British military training. Similarly, the British Cabinet was told that the Royal Air Force support to Denikin was in a training role, though in fact the 47th Squadron, a combat division, was sent, and in the battle of Tsaritsyn – ‘British planes bombed and strafed the Red positions and lines of communication on a daily basis’. Under public pressure over its undeclared war in Russia, the Cabinet announced that the 47th Squadron was disbanded – though in fact just the name was changed and the bombardments carried on.7

Despite the British, French and American allies’ attempt to distance themselves from direct responsibility for the ‘White Army’ and their campaign, it became clear that without western support Denikin, Kolchak and the rest had no real appeal to the mass of Russian people. Rich in British arms, their troops melted away. The barbarism of the White Armies, though, was legendary. A letter written by one White Army executioner on the Don gives a flavour of their approach:

The harvest was pretty good and every evening, apart from the tribunal, numerous Bolshevik prisoners were disposed of – sometimes a hundred, sometimes three hundred, and in one night 500 were dispatched. The mode of procedure was as follows: fifty men dug their own common grave, then they were shot and the other fifty men would cover them up and dig a new grave, side by side, and so on. There are so many of them that we have decided to their great discomfiture to turn Red Guards into slaves.8

Red Army commander Leon Trotsky protested:

the women and children of Archangel and Astrakhan are maimed and killed by English airmen with the aid of English Explosives. English ships bomb our shores...

Churchill’s undeclared war against Russia was deeply unpopular in Britain. The Press called it Mr Churchill’s Private War. A ‘Hands Off Russia’ campaign was very successful. One of its organisers, William Paul, wrote that ‘If labour in this country can exert itself to protest effectively in every field of activity, then it may compel the British Government to abandon its armed expedition in Russia.’ London dock workers refused to coal the SS Jolly George, a munitions ship on its way to Russia. Rail workers also tried to disrupt the munitions going to the intervention forces.9

1919-21: The War of Independence in Ireland

More than 200,000 Irishmen fought for Britain in the Great War, and around 40,000 lost their lives. But from 1916 to 1922 Britain fought a war against a risen Irish people, determined to be free. In 1916 the British forces put down the Easter Rebellion executing its leaders. But the country was still in open defiance. Mass meetings outside churches committed the faithful to refuse conscription and in much of the country the Irish Republican Army was the acknowledged law. The United Kingdom’s General Election of November 1918 saw Sinn Fein candidates elected in 73 of the 101 constituencies in Ireland. The Sinn Fein MPs would not sit in Westminster, but declared themselves representatives of an Irish Parliament, the Daíl.

The Auxiliary ‘Black and Tans’ wreaked havoc in Ireland

From among its demobbed soldiers Britain recruited an ‘Auxiliary’ force of 14,000 to back up the Royal Irish Constabulary, known, because of their mix of black police and khaki military uniforms, as the ‘Black and Tans’.

The auxiliaries and the RIC imposed ‘a state of government terrorism’ according to the New Statesman. In September 1920 they sacked Balbriggan, terrorising the citizens of that town, murdering two Irish nationalists, beating many others and burning many shops and houses. On 21 November – Bloody Sunday – the auxiliaries and the Royal Irish Constabulary opened fire on the crowd at a Gaelic football match at Croke Park. Fourteen were killed and at least 60 wounded.10

India: 1919

The contribution of the British-Indian Army to the war was profound. With an army of more than a million men India’s army was as many again as those who fought in the British Army. Indian troops fought courageously at Ypres, Neuve Chapelle and Gallipoli. In the Middle East and North Africa, Indian troops shouldered the lion’s share of British efforts. At the end of the war they had a real expectation that they would be rewarded with self-government, comparable to that enjoyed by Canada, Australia and New Zealand. But they were betrayed. The ‘Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms’ of 1918 offered no substantial role to Indians in their own government beyond the lowest local questions (less than half of the legislative council members were to be elected, and power retained by the governor). British MP Vickerman Rutherford declared that:

Never in the history of the world was such a hoax perpetrated on a great people as England perpetrated upon India, when in return for India’s invaluable service during the War, we gave to the Indian nation such a discreditable, disgraceful, undemocratic, tyrannical constitution.

Denying any meaningful self-government, the British administration went one step further, when the puppet legislative council passed the ‘Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act of 1919’, known as the ‘Rowlatt Act’ after the judge Sir Sidney Rowlatt, whose committee drew up its provisions. Under the Rowlatt Act, suspects could be detained indefinitely, tried in camera and allegations made anonymously – all adding up to a fearsome set of measures to silence and intimidate Indian nationalists.

In March and April of 1919 a number of stoppages – hartals – were made to protest against the Rowlatt Act. On 9 April the government responded by jailing two nationalist leaders in the Punjab: Dr Saifuddin Kithclew and Dr Satyapal. There were riots in the town of Amritsar. The police opened fire on the crowd killing ten, and in the rioting that followed five Englishmen were killed. The town was shut down by Brigadier General Reginald Dyer. On the 13 April a religious festival, Baisakhi, drew crowds of 10,000 or more, who were gathered in the walled gardens called Jallianwala Bagh. Dyer ordered his men to surround the garden and open fire on the crowd, until their ammunition was spent. Three hundred and twenty-nine people were killed outright and 1179 were wounded after 1650 rounds were fired.

Despite sending more than a million soldiers to fight for Britain in the Great War, Indians were refused self-government afterwards

Shocking as it was, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre was only the culmination of Dyer’s reign of terror. He arrested students and teachers and made them crawl on their bellies in the street. He had hundreds of people flogged and built an open cage in the town centre to detain people. He had Sadhus painted with quick lime and left to dry in the sun. And he had aircraft bomb villagers as they worked in the fields.11

Iraq: 1920

An uprising of Arabs and Kurds against the imposition of the Sykes-Picot division of Arabia came quickly after the end of the war. In May of 1920 they rose against the 100,000 British and Indian troops that were holding the territory.

The Royal Air Force:

flew missions totalling 4,008 hours, dropped 97 tons of bombs and fired 183,861 rounds for the loss of nine men killed, seven wounded and 11 aircraft destroyed behind rebel lines. The rebellion was thwarted, with nearly 9,000 Iraqis killed.12

The Air Minister, Lord Thomson, wrote about one district of ‘recalcitrant chiefs’ in the Liwa region on the Euphrates in November 1923: ‘As they refused to come in, bombing was then authorised and took place over a period of 2 days. The surrender of many of the headmen of the offending tribes followed.’13

The bombardment of Iraq was a big step for the Royal Air Force. The government congratulated them on achieving air superiority to hold land that even thousands of troops could not. The RAF felt they had learned that aerial bombardment could cow populations. British military leaders broke the taboo against aerial bombardment in Iraq. One of the squadron leaders there was Arthur Harris who, in 1942, would organise the campaign to destroy Dresden and other German cities by air power.

In 1939 Britain and Germany were once again at war, and once again the war became a world war. (We have written about this before in the 2011 book Unpatriotic History of the Second World War). In total 60 million lost their lives. Today we look at the Second World War as a struggle between democracy and Fascism. But at the time much of what the British Army did was to fight over who controls the colonies. Between 1940 and 1944 the contest between Germany and Britain was fought over possession of North Africa – without any thought for the people who lived there. Elsewhere, too, the British Army fought for the possession of strategic territories.

Iran: 1941

In 1941 Britain invaded Iran, deposing Reza Shah and putting his 21-year old son Reza Pahlavi on the throne. The British-Indian Army occupied the oilfields at Mosul. The action was coordinated with the Soviet Union, which invaded the north of the country as the British-Indian Army invaded the south. Maintaining order in occupied Iran proved a disaster for the Iranians. Making it the supply hub between the Soviet Union and British India skewed the economy dangerously. The allied forces buying power contrasted with the low wages of Iranians led to a spiral of inflation that pushed bread out of most people’s price range. Hunger led to rioting. On 8 December 1942 British troops fired on protesting students, killing scores and wounding hundreds.

India: 1942

On 7 August 1942, frustrated at the decades of British opposition to self-rule, the All-India Congress Committee meeting in Bombay passed a resolution demanding that Britain ‘Quit India’. Within 36 hours the entire leadership of the Congress Party was jailed. In the first wave 60,222 protestors were arrested and 18,000 jailed under the Defence of India Rules. The total eventually jailed rose as high as 90,000.

Britain’s suppression of the Quit India movement drew British troops away from the conflict with Germany, and troops fired on Indian protestors. At the time the numbers killed were acknowledged to be hundreds but estimates today put the total at around ten thousand. To impose order, the British brought in a ‘whipping act’.

With the Congress leaders in jail, India was dangerously unstable. Britain was holding the country by force, but still dependent upon India’s tax base and its soldiers to fight the Second World War. Bengal’s grain was being used to feed the Ceylon rubber workers. Churchill had been warned that the state was dangerously undersupplied, but the War Cabinet ignored the prospect of famine. They were not just indifferent, but hostile to Bengalis, many of whom were sympathetic to the Indian National Army, which was working alongside the Japanese to overthrow British rule. As the Japanese forces advanced towards Bengal, the British authorities set about making sure that the province was inhospitable, wrecking boats, bicycles and even cooking pots as the remaining grain stores were relocated out. The famine was drastic. Eventually as many as 3.5 million died. Subhas Chandra Bose, leader of the Indian National Army, offered aid to Bengal from the grain surplus in Burma, but fearing a propaganda coup, the British administration refused the offer.

‘Dekemvriana’: 1944

ELAS resistance fighters liberated much of the inland of Greece taking on the Italian and German occupation forces between 1940 and 1944. They were on paper British allies. But in 1942, the exiled Greek Army in Egypt had rebelled against their Royalist officers in favour of the new partisan leadership. The British responded by turning their guns on the Greeks and putting them in camps without water or food to break their will. Churchill knew how determined the Greek resistance fighters were, but he also had an agreement with Stalin that Greece would be part of Britain’s ‘sphere of influence’ after the war. In 1944 as the German forces were on the retreat, and without telling the Cabinet, Churchill ordered General Scobie ‘to act as if you were in a conquered city where a local rebellion was in progress’. ‘We have to hold and dominate Athens,’ he added.

The 2nd Parachute Brigade and the 5th (Scottish) Parachute Battalion were among those used to suppress the victorious Greek resistance. In Syntagma Square a parade of national liberation was fired upon leaving scores dead. In Greece these came to be known as the Dekemvriana, the ‘December Days’. By the end of December the British forces were 75,000 strong. To defeat the ELAS resistance the British recruited also the same ‘Security Battalions’ who had been organised by the German occupation. The Security Battalions were known for their violence and barbarism. To show their success rate they handed sacks of the severed heads of Greek ELAS fighters to their British handlers.

Britain’s allies in Greece, the Security Battalions assassinated the leaders of the wartime resistance to Nazi rule

Malaya: 1948-58

In the Second World War the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army had fought to free the country, with the support of the British. They were led by Chin Peng and drew on Malaya’s large ethnic Chinese population. After the war the British backed decolonisation but under a constitution that disenfranchised the Chinese. To enforce the new constitution Britain sent troops to suppress dissent. Mostly the dissenters were ethnic Chinese, rubber and tin workers and squatters in the forests, but the British branded them ‘Communist Terrorists’ and set about a brutal campaign against them. The same Chin Peng who had been honoured by the British for fighting against the Japanese was now branded ‘Enemy Number One’. High Commissioner Gerald Templer developed a policy for isolating rebel bands by establishing ‘an outer ring of ambushes to prevent an exodus from the killing ground’. After starving the bands for a month or so, Templer’s men embarked on ‘the killing stage’.

In 1948 soldiers of the Scots Guards shot dead 24 unarmed Malaysian villagers at the rubber plantation by Batang Kali village, and then covered up the massacre. According to one of the soldiers, the sergeant told them that ‘the villagers are going to be shot and we could fall in or [opt] out’.14 One officer recalled:

we were shooting people. We were killing them…this was raw savage success, it was butchery. It was horror.

An insight into what the British Army was getting up to in Malaya came when the Daily Worker published a photograph of a soldier posing with the heads of two Chinese rebels, one in each hand.

As well as direct engagement, the Royal Air Force was called on to carry out aerial bombardment. There were 4500 air strikes in the first 5 years of the ‘Malayan insurgency’. One rebel stronghold was bombed in 1956 with 545,000lbs of bombs, at the beginning of May 1957 with 94,000lbs and then on 15 May with another 70,000lbs.

To try to undermine the popular support for the rebels the British used a policy of relocation into village camps, behind barbed wire. Half a million Chinese were relocated, usually into degrading and impoverished conditions – though the Colonial Office called it ‘a great piece of colonial development’. As well as the relocation policy, some 34,000 Malays – mostly of Chinese origin – were detained and some 15,000 exiled altogether.

Decolonisation in Malaya proved to involve even greater domination by the British Army. British strategy was to defeat the nationalist movement before withdrawing, so guaranteeing the installation of a supplicant elite, well-tutored in the terror of British fire power and implicated in the suppression. As many have noted since, the determination to dominate the national movement was also inspired by the economic needs of the British Empire, its reliance on earnings from rubber plantations and tin mines in the immediate post-war period. The anti-insurgency campaign had the advantage of silencing labour activism on the plantations and securing Britain’s extensive investments in ‘independent’ Malaya.15

1952-6: Mau Mau uprising

Around 100,000 Kenyans had joined the British forces in the Second World War. When they returned home there was no hero’s welcome. European settlers kept the best land in the Central Province uplands – known as the White Highlands – for themselves. Kenyans squatting the land the Europeans did not farm were tolerated as long as they worked as farm labourers – but kept on pitiful wages and evicted when they could no longer work. There was a nationalist campaign, the Kenyan African Union, led by Jomo Kenyatta. But many of the Kikuyu squatters despaired at the glacial pace of change.

A secret society, the Mau Mau, was formed among the Kikuyu squatters. It met at night and bound its members together with a secret oath, much like the rural followers of Ned Ludd in early nineteenth century Britain. They burnt white farms and tried to intimidate those who dealt with them badly. The British authorities reacted with fury.

Though Kenyatta had publicly disowned and denounced the Mau Mau rebels, he was tried for supporting them and sentenced to 7 years in jail. Waging war on the Mau Mau itself the British Army killed as many as 10,000 Kikuyu and other African people. Men were tortured and mutilated with ears and fingers cut off, and beaten all over, often on the soles of the feet and around the groin. The British Army kept score cards to list their ‘kills’ and paid a £5 reward for the first subunit to kill an insurgent. Apart from those killed in the field, the official execution list recorded 1015 hanged between 1952 and 1956, 297 for murder, 559 for unlawful possession of a firearm or for swearing a Mau Mau oath.

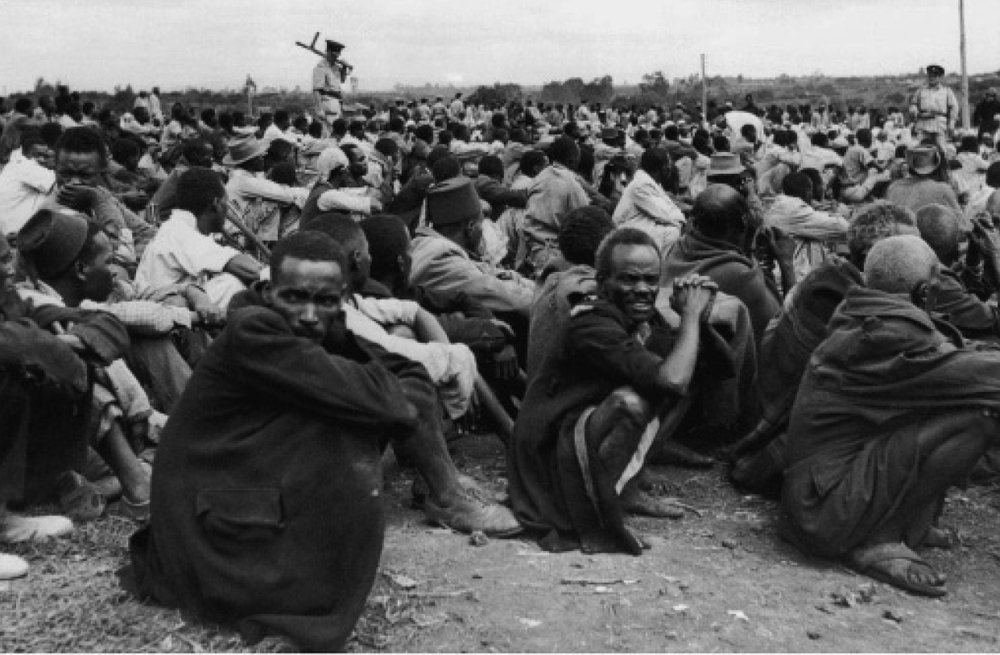

Mau Mau suspects held in a British concentration camp, 1953

The army cleared 80,000 Kikuyu from the ‘White Highlands’ and put them behind barbed wire in ‘Native Land Units’. This ethnic cleansing led to thousands more deaths. In one camp 400 people came down with Typhus and 90 of them died. One camp commandant later admitted that the Kikuyu detainees were subject to ‘short rations, overwork, brutality, humiliating and disgusting treatment and floggings – all in violation of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights’. The British governor asked the Colonial Secretary in London whether forced labour could be formally re-introduced for the Kikuyu, but he was told that this would be too difficult to manage with world opinion. In the event, the Kikuyu in the camps, as well as the Mau Man prisoners, were regularly subject to forced labour and beatings.16

1956 Suez

After the Second World War Egypt had been governed by King Farouk, with the help of the British and the Wafd party. In 1952 a coup by the Free Officers Movement, whose de facto leader was a young Corporal Gamal Abdel Nasser, promised Parliamentary elections and an end to corruption. In 1956, as President of the Revolutionary Command Council, Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal Company, owned by Britain and France. British Prime Minister Anthony Eden thought that Nasser must be ‘got rid of’, ‘destroyed’, ‘murdered’.17 With the support of Israel and France, Britain planned to invade.

In November 1956, after Israel attacked Egypt, British paratroopers landed to seize Port Said and the neighbouring area. Seven hundred and fifty Egyptians were killed in the attack. One of the paratroopers remembered ‘several Wogs appeared running down the street in front of us’: ‘we kept shooting all the time’. The United Nations forced Britain to accept a ceasefire of 6 November, at the prompting of the United States, whose leaders thought the adventure foolish and dangerous.

Cyprus: 1955-9, 1974

In 1955 a guerrilla group called EOKA (National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters) took up arms against the British colonial authorities on the island. Their goal was freedom from British rule, and ‘Enosis’, union with Greece, and they were led by Georgios Grivas. ‘I can imagine no more disastrous policy for Cyprus than to hand it over to a friendly but unstable power. It would have the effect of undermining the eastern bastion of NATO,’ said the Colonial Secretary, Oliver Lyttleton:

Eastern Mediterranean security demands that we maintain sovereign power in Cyprus.

There were around 1250 EOKA fighters arraigned against 30,000 British troops. There were 1144 exchanges recorded between EOKA and the British forces, and EOKA killed 105 soldiers and another 50 policemen. In 1959 EOKA was persuaded to lay down its arms in exchange for an independent government for Cyprus.

The victor in Cyprus’ first election – with 70 per cent of the vote – was Archbishop Makarios who had been exiled from the country by the British authorities. He proved a popular leader in Cyprus but was despised in London and Washington where he was called the ‘Castro of the Mediterranean’. In collusion with the Conservative military government in Greece, Georgios Grivas took up arms against Makarios destabilising his government. In 1974 with the connivance of the British and Americans, Turkey invaded the northern part of the island setting up a Turkish government there. The conflict led to a coup against Makarios and a brutal division of the island.

The Aden emergency: 1963-7

In 1956, a young man on his National Service bundled on to a great barge of a troop carrier that made its way lazily through the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal (when you could) with 300 other bored, sunburnt, young men on their way to fight Chin Peng’s Malaysian guerrillas.

As they approached the Arabian Peninsula, they were gathered for emergency briefings by their officers: a rebellion had broken out in Yemen – then known as the British colony of Aden and its hinterlands – and they were to land at Aden and put it down. Arriving at night, the squaddies were armed with two-foot batons, and told to put some stick about. There was fighting all through the market port, but in time the British Army prevailed and the Yemenis, bloodied and bruised, cleared the streets. Not much later, the troops were back on the barge, on their way to hunt down Chin Peng.

It was only on the boat, piecing together all their stories as they celebrated another victory for British fair play, that the men worked out that there never had been a rebellion in Yemen. The only fighting that the citizens of Aden did was in reply to the battering that they were getting from the squaddies, and that was mostly just stone-throwing here and there. The whole thing had been made up by the British officers so that their troops would be able to get some action in, let off a bit of steam, and arrive in Singapore with a bit of confidence. In Singapore the soldiers chatted with men who had been there longer. It turned out that the ‘rebellion in Aden’ was an exercise they had all been on.

In 1963, inspired by Gamal Abdel Nasser’s revolution in Egypt, there was an uprising in Yemen. British troops were sent in to put it down. In Aden, in 1966, the British officer commanding, Lieutenant Colonel Colin ‘Mad Mitch’ Mitchell’s brutal war against the guerrillas span so far out of control that he was made to resign. The officers had initiated inter-platoon rivalry by awarding Robertson’s jam golliwog stickers to units for each killing of an Arab.18

British troops in Aden

In the hinterland, the British used air power to break support for the rebels, as Captain R. A. B. Hamilton of No. 8 Squadron explained:

The Air Staff would work in the closest contact with the political officer. It was my task, equipped with a portable wireless set, to camp as close to the scene of operations as I considered possible, so as to facilitate the surrender of the tribe and to reduce the extent of the operations to a minimum, Two, and one-day warnings were dropped on the tribe, followed by an hour’s warning before the first attack, so that women and children could be taken to a place of safety and every effort was made to inflict losses to property rather than lives.

The concept of ‘proscription’ bombing meant that once the leaflets had been dropped, all humans and livestock were legitimate targets within the proscribed area.19

In 1967, Yemeni soldiers in the British-backed force were in mutiny and attacked the British troops, killing several. Having lost all support among the Yemenis, Britain withdrew and the National Liberation Front declared Yemeni independence.

Ireland, the longest war: 1969-2007

After the partition of Ireland at the end of the war of independence the six northernmost counties were kept part of Britain and ruled by the Ulster elite as ‘a protestant state for a protestant people’. Catholics in the six counties were disenfranchised by gerrymandering of constituencies, and the additional votes afforded businesses, so that all power was in the hands of the unionists. Jobs and social services, too, were kept to the ‘loyal’ Protestant community, leaving many Catholics living in overcrowded slums, with long stretches out of work.

In 1967 the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) was set up to fight for ‘one man one vote’. Its marches were immediately the target of violent attacks by the Royal Ulster Constabulary and the ‘B Specials’. The ‘B force’ of the Ulster Special Constabulary was recruited out of Edward Carson’s paramilitary UVF in October 1920. From then it was on hand as a special sectarian squad to attack Irish nationalists.

On 5 October 1968 NICRA marched in Derry. ‘Demonstrators were beat down on the streets.’ The more radical People’s Democracy organised the next march from Belfast to Derry. The Royal Ulster Constabulary marked the student protestors closely until they came to a bridge at the town of Burntollet on 4 January 1969. A crowd of around 300, mostly off-duty B Specials, attacked the march with a truck load of stones brought from a nearby quarry and beat them with batons.

That summer loyalists planned to attack the Catholic ‘Bogside’ area of Derry under the cover of the annual Apprentice Boys march. The ‘B Specials’ were deployed to support them. To their surprise the Bogside organised itself as the Citizens Defence Committee, raised barricades across the streets, and fought the B Specials and the Apprentice Boys to a standstill. Tommy McCourt remembered, ‘we thought the cops might get in, but they stopped as they came to the barricade’: ‘That gave everyone the initial boost that we’d stopped them.’ The fighting between the Bogsiders and the RUC went on for 3 days, but Derry remained free.20

After the battle of the Bogside, British troops were sent in to ‘restore order’. The deployment was called Operation Banner, and it lasted from 1969 to 2007: 38 years. At its height the British military presence in Northern Ireland stood at a remarkable 30,000 troops. At first they were welcomed by some among the nationalist population, but the honeymoon did not last. The British Army took its cue from the politicians who were determined that Britain would not surrender authority in Northern Ireland. That meant that the army were quickly put to use enforcing the suppression of the nationalists.

The Ulster Defence Regiment was created in 1969. In Parliament the MP and civil rights leader Bernadette Devlin challenged Defence Minister Roy Hattersley: ‘Can the honourable gentleman give me one concrete statement to show that this is not the Ulster Special Constabulary under the guise of the British Army?’ Since it was formed a hundred UDR members have been charged with sectarian murder and over a thousand have reported their weapons ‘lost’ or stolen.

In 1970 the army’s overall commander in Northern Ireland, Ian Freeland, announced that people with petrol bombs would be shot. That summer Bernadette Devlin was arrested and nationalists rioted. The army imposed a curfew on the Falls Road in Belfast. The army killed four people, including a journalist covering the story.

In February 1971 the army carried out raids in nationalist Belfast leading to 3 days of rioting. In retaliation the Provisional Irish Republican Army, which had been set up the year before, shot dead Private Robert Curtis, the first serving soldier to die in the conflict.

That August the army launched Operation Demetrius, raiding the homes of those who were on the police’s list as Republican sympathisers. A total of 342 people were arrested on suspicion of being in the IRA, and, in a sinister new step, were interned in a camp in a former RAF base called Long Kesh. The policy of internment without trial was uniquely unpopular – quite apart from the fact that many of those who were picked up were plainly not any part of the IRA.

On 30 January 1972 a massive demonstration against the internment policy began. General Ford, the army’s second in command, had already prepared a memo to General Tuzo saying that ‘the minimum force necessary to achieve a restoration of law and order is to shoot selected ringleaders among the’ people he called the ‘Derry Young Hooligans’ (not a name they chose for themselves). The argument that the leaders of the Civil Rights protests ‘were enemies of the Crown and should be liable to being shot’ was made by Lord Hailsham at a Cabinet Committee the previous year. Ford’s plan was approved by the Prime Minister, Edward Heath. The general ordered a parachute regiment into Derry to challenge the protest, against advice from the RUC. Under Lt Col Derek Wilford the regiment opened fire killing 13 protestors. Ever after the day was known as ‘Bloody Sunday’.

After Bloody Sunday the Irish Republican Army challenged British rule in the six counties. There were so many volunteers they had to turn them away. The demand for civil rights within a reformed British state had given way to a revived belief that all 32 counties of Ireland could and should be united and free.

In May 1974 a clandestine unit of the Ulster Defence Regiment made up of Billy Hanna, Robert McConnell and Harris Coyle planted four car bombs in the Irish Republic, in Dublin and Monaghan, that killed 33 people and injured another 300.

Lenny Murphy led a gang of sectarian killers, the Shankill Butchers, who were prosecuted for 19 killings, and, according to author Martin Dillon, probably responsible for another 13. Murphy liked to have his victims hang on a rope while he beat and hacked at their bodies ‘much in the manner a sculptor would chip away at a piece of wood or a stone’. Among their number was a member of the Ulster Defence Regiment, Edward McIlwaine. They were assisted by John McFarland Fletcher, a sergeant in the UDR.

Britain’s dirty war in Northern Ireland terrorised the nationalist population there. But it did not limit support for the Irish Republican Army or opposition to the British presence. Rather, support for republicanism grew stronger. The numbers interned in Long Kesh grew from around 500 to more than a thousand.

In 1976 Northern Ireland minister Merlin Rees attempted to take back the initiative by reclassifying the interned as criminals, not ‘Special Category’ prisoners. They were made to wear prison uniforms, and ‘convicted’ by special ‘Diplock courts’ that sat without a jury. The prisoners protested the change demanding to be recognised as prisoners of war. After being confined to their cells and stopped from ‘slopping out’, the prisoners started a hunger strike. In May 1981 Bobby Sands, an IRA prisoner, died in Long Kesh after 66 days without food – to be followed by nine more hunger strikers. Shortly before Sands died he had been elected in absentia to the Parliamentary seat of Fermanagh and South Tyrone. More than 100,000 stood to watch his funeral cortege. Support for the political wing of the Republican movement climbed and they won elections in Derry, West Belfast and Fermanagh.

British repression only provoked greater opposition from Northern Ireland’s nationalist community

After the upsurge in republican support, British forces began an active policy known as ‘shoot-to-kill’. A military group within the Royal Ulster Constabulary called the Headquarters Mobile Support Unit carried out pre-emptive attacks on republicans. In 1982 they shot Michael Tighe and Martin McCauley after waiting for them to return to a weapons dump in a barn. The same year they shot dead Seamus Grew and Roddy Carroll at an RUC checkpoint in Mullacreavie, County Armagh.

Another undercover squad, the Forces Research Unit, ran agents within the loyalist Ulster Defence Association (UDA), including Brian Nelson. Rather than spying on the UDA, they were using Nelson and other loyalists to assassinate republicans. The Forces Research Unit also burnt down the offices of the police chief John Stevens who was called in to investigate the ‘shoot-to-kill’ policy. In 1989 the human rights lawyer Pat Finucane was shot dead in his home by Ken Barrett. The UDA claimed responsibility for the killing but later they were found to have been helped by the Forces Research Unit.

In June 1991 IRA volunteers Tony Doris, Pete Ryan and Lawrence McNally were ambushed in their car by a Special Air Service shoot-to-kill squad in East Tyrone. Two hundred rounds were fired into their car, which burst into flames. The SAS left the car to burn as a lesson to their families.

In May 1992 the parachute regiment based in Coalisland, County Tyrone rioted attacking local bars. Feargal O’Donnell was savagely beaten across his face. He had eight stitches to close the wound. Attacks like these were commonplace, but this time Feargal’s friends fought back. As a crowd gathered to protest the beating, the paratroopers opened fire, wounding three people. Stop and search was a daily event for the young men of the town. ‘At Christmas I got tarted up five times and never made Dungannon once,’ one man told Fiona Foster. ‘I spent two nights in Aughnacloy search centre.’21

Britain’s war in Northern Ireland wound down when a political compromise was agreed between the Irish Republican Army and the British Government in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. In exchange for a ceasefire the British guaranteed representation for Irish nationalists within a devolved assembly at Stormont Castle. One thousand and forty-nine from the Crown forces were killed in the fighting, including 705 from the army and 301 from the RUC. Three hundred and thirty-eight Republican fighters were killed, and 1193 civilians.

The Falklands War: 1982

On 2 April 1982, 600 Argentine troops landed at Port Stanley on the Falkland Islands and seized Government House. The islands are 300 miles from Argentina and 8000 miles from Britain. In 1833 Britain seized the Malvinas Islands from Argentina and renamed them. Most of the island is owned by the Falkland Islands Company, created by Royal Charter in 1851. At the time of the invasion the population was 1800.

Britain sent a task force of 100 ships and 26,000 men. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher explained that it was about prestige: ‘Since the Suez fiasco in 1956, British foreign policy had been one long retreat’ which she was determined to reverse. Thatcher declared a 200-mile ‘exclusion zone’ around the islands – extending into Argentina’s territorial waters. But when the Argentine cruiser the Belgrano was outside of the exclusion zone, it was fired upon and sunk with the loss of 323 men.

On 21 May 4000 men of the 3rd British Commando landed at San Carlos Bay on the other side of East Falkland, before moving over land to Goose Green and Port Stanley, which they reached on 11 June. After a short battle, the overwhelmed Argentine troops surrendered. There were reports of Argentine prisoners executed after surrendering. One, Corporal Oscar Carrizo, was shot through the head at Mount Longdon after giving up his weapons and jacket. Remarkably, he survived – others were not so lucky:

Also at Mount Longdon, Nestor Flores reports seeing British troops murder privates Quintana, Graminni and Delgado. Corporal Gustavo Osvaldo Pedamonte witnessed the murder of privates Ferreyra, Mosconi, Petruccelli and Maldana by British soldiers. To this must be added the confession of a British former Lance Corporal in 3 Para, who described how he and a colleague had machine-gunned three prisoners they believed to be American mercenaries (who were probably US-educated Argentinians). Ex-Captain Mason says that he told a colonel about the killings at the time. Nothing was done and the colonel has since been promoted to major-general. Similarly, Lucas Morales of Argentina’s fifth marine battalion describes being shot at by British troops after surrendering after the battle of Mount William. One British soldier killed during the battle was even found to have a bag full of severed Argentinian ears…

Even after the surrender, Argentine prisoners were executed:

Epifanio Casimiro Benítez testified to further executions of wounded prisoners on 16 July 1982 after the total surrender of Argentinian troops in the Malvinas Islands. Captain Horatio Alberto Bicain claims that he saw British troops kill Captain Artuso after his submarine Sante Fe had been captured.22

The war over the Malvinas/Falklands was first and foremost a propaganda exercise. The Falkland islanders’ rights were not important to the British Government. Only the year before they had refused an earnest plea from the islanders over the changes in the 1981 Nationality Act that made several hundred of them stateless. Two hundred and fifty-five British servicemen lost their lives in the war. Fifty-six were killed when Argentine aircraft attacked troops landing at Port Pleasant on 8 June 1982. The Royal Navy lost 86 in the Argentine attacks on the ships the Ardent, the Glamorgan, the Sheffield and the Coventry. Six hundred and forty-nine Argentinians were killed – more than half of them in the sinking of the Belgrano. The sacrifice of life, Argentine and British, was all to defend Britain’s prestige in the world.

The British Army in the ‘New World Order’

In 1991 the Soviet Union was dissolved and the geopolitical contest, the Cold War, that dominated military thinking since 1947 was at an end. US President George H. W. Bush announced a ‘New World Order’. Expectations of a ‘peace dividend’, that swords would be beaten into ploughshares, were disappointed, though. The western powers’ victory found them without an enemy, and so without a raison d’etre. Colin Powell, when chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, said: ‘the Soviet Union is gone, the Warsaw Pact is gone, you know, I’m running out of enemies’. In their search for bogeymen to frighten the populace, America went to war against Saddam Hussein and Slobodan Milosevic, but most people could see that these were minor figures, really just whipping boys for the military. As Powell said, ironically, he was ‘down to Fidel Castro and Kim Il Sung’. Arbitrary wars were launched, often against former allies from the Cold War era. Their main purpose was not to win wars abroad, but for political leaders to rediscover a sense of purpose at home. Instead of conquering territory and wealth, western leaders pumped themselves up as champions of human rights and ethical intervention.

British soldiers caught up in this new humanitarian imperialism quickly discovered that they were expendable in the struggle for moral authority at home. When military intervention went wrong, soldiers were often blamed for what their generals had commanded them to do. Civil prosecutions of troops for atrocities that were ordered from on high was a further sign of the bad faith of the new humanitarianism.

Bosnia, 1995; Kosovo, 1999

In 1995 the Royal Air Force took part in NATO attacks on the Bosnian Serb forces in the civil war. NATO flew 3515 sorties and a total of 1026 bombs were dropped on 338 Bosnian Serb targets. British forces also took part in the UNPROFOR forces’ artillery attacks. In the wake of the peace talks later in 1995 British forces took part in the ‘Stabilisation Force’ that occupied strategic points in Bosnia. The whole of the Former Yugoslav Republic was placed under a UN ‘High Representative’ with dictatorial powers to direct and suspend political government. The ‘resolution’ of the conflict was no such thing, but rather an open invitation to other forces in Yugoslavia to take up arms against their government.

The Kosovo Liberation Army was founded in 1996 to press for the separation of the Yugoslav province. The KLA took up arms against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1998 and was rewarded with a place at UN sponsored peace talks. When Yugoslav forces took action against Kosovans, NATO launched a prolonged series of air attacks in Kosovo, and against the Yugoslav capital, Belgrade. Rather than calm the conflict the intervention led to more attacks on Kosovans by Yugoslav forces. British Prime Minister Tony Blair tried to persuade US public opinion to support a ground force in Kosovo, earning the jibe that he was willing to fight to the last drop of American blood. Relying on air power, however, the allied forces were only committed to destruction. On 14 April 1999 the allies bombed a convoy of Kosovo Albanian refugees at Korisa – the very people they claimed to be helping – killing 87.

The Royal Air Force played a significant role in the bombardment of Kosovo and of Belgrade. Around 600 people were killed in Kosovo and 5000 in Yugoslavia overall. The citizens of Belgrade protected their bridges from 72 days of aerial bombardment by making themselves ‘human shields’ – standing on the bridges at night with target signs. Bomb damage to Yugoslavia was estimated at $26 billion. The USAF bombed the Chinese Embassy killing three Chinese reporters. At the time this was claimed to be a result of poor intelligence though it was later shown to be deliberate targeting.23 In the aftermath of the conflict, 7000 British troops took part in KFOR – a ‘stabilisation force’. Under its jurisdiction 20,000 ethnic Serbs were forced out of Kosovo.

Iraq: 1991, 2003

Under Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990. Before then Saddam had been supported by both Washington and London, both because he was a ‘strong man’ who would face down local radicals, but also later because he was at war with Iran, which since the revolution of 1979 had been a thorn in the side of the western powers. British arms firms’ sales to Iraq were supported by the export credits guarantee department – an agency of the Department of Trade and Industry. Thorn EMI, Racal and Marconi Command and Control all made sales to Iraq valued in the millions, underwritten by the ECGD. Saddam Hussein had every reason to expect that the encouragement he got from London and Washington would continue. Broaching the possibility of an invasion of Kuwait, as Iraqi troops massed on the border, US Ambassador April Glaspie assured Saddam that:

we have no opinion on the Arab-Arab conflicts, like your border disagreement with Kuwait. …

James Baker has directed our official spokesmen to emphasize this instruction. (New York Times, 23 September 1990)

When the invasion went ahead Saddam’s move was roundly condemned. Strangely, America’s military were already prepared for a war against Saddam. While serving as Commander-in-Chief, United States Central Command, Norman Schwarzkopf pointed out that the army would have nothing to do if the Cold War with Russia was over. He worked overtime to throw out the old ‘Zagros Mountains plan’ which assumed a Soviet invasion and replaced it with ‘Internal Look’. The new plan assumed an Iraqi invasion to seize Saudi oil fields. In late July 1990, Schwarzkopf staged a mock-up of ‘Internal Look’ just 2 weeks before Iraq invaded Kuwait. As he says himself, ‘the movements of Iraq’s real-world ground and air forces eerily paralleled the imaginary scenario in our game’ – but then that was the point: the US planned and engineered the conflict from the start to the withdrawal of their troops, as an exercise in confidence-building and demonstrative performance of world power.24

President George H. W. Bush used the United Nations to rubber stamp a US-led coalition to defeat Saddam. Margaret Thatcher promised ‘to send the 7th Armoured Brigade to the Gulf, comprising two armoured regiments with 120 tanks, a regiment of Field Artillery, a battalion of armoured infantry, anti-tank helicopters and all the necessary support’. ‘It would be a completely self-supporting force, numbering up to 7,500.’ Later she also sent:

the 4th Brigade from Germany, comprising a regiment of Challenger tanks, two armoured infantry battalions and a regiment of Royal Artillery, with reconnaissance and supporting services. Together the two brigades would form the 1st Armoured Division. The total number of UK forces committed would amount to more than 30,000.25

Coalition forces dropped 88,500 tonnes of bombs in 109,000 sorties. In all 250,000 bombs were dropped, and only 22,000 of these were ‘smart-bombs’ (guided missiles). The bulk of the bombing was carried out by B52s flying at 40,000 feet. The death toll was around 180,000. British Prime Minister John Major was under pressure from some to pause the bombing, but not from Labour leader Neil Kinnock, who said, ‘to be blunt, the best time to kick someone is when they are down’.26

Under Major-General Rupert Smith, Britain’s 1st Armoured division took part in the attack on Iraqi forces retreating from Kuwait, the Battle of Norfolk, the biggest tank battle in the war, on 27 February 1991. British forces also took part in the attack on the retreating Iraqi forces on the Basra High Road on the same day. The Iraqis were bottled in when allied air forces attacked the roads out of Kuwait and destroyed them. Kill zones were assigned every 70 miles along the road. More than 2000 vehicles were destroyed and 25,000 killed. RAF Marshall David Craig said that the attack began to look ‘more and more like butchery’. Elsewhere, an RAF Tornado squadron leader ‘who bombed a suspension bridge admitted that the bridge was in the centre of a populated area’: ‘Yes there will be civilian traffic,’ the pilot said, ‘but they could well be civilian contractors working on an airfield.’27

After inflicting a traumatic defeat on the Iraqi Army and the country, British Prime Minister John Major’s proposal to create ‘safe havens’ from the air to stop attacks on the Kurdish minority laid the basis for RAF and USAF imposed ‘no-fly zones’. As BBC correspondent Mohammed Darwish explained, there were ‘continued air strikes in the south and north of the country where British and American planes are attacking under the disguise of patrolling the no-fly zones’. So, on 16 February 2001, British Tornado jets joined US F-15 aircraft bombing Baghdad on the claim that Iraqi forces were set to attack the RAF imposed ‘no-fly zone’ over northern Iraq.28

Iraq was subject to an embargo of food from September 1990 under the presciently numbered UN resolution 666. Sanctions remained in place with the modification that Iraq could – on condition it surrendered its oil exports to the UN – get food aid in return (while the UN deducted a percentage for costs). Denis Halliday, who managed the ‘food for oil’ programme, resigned in 1998, saying that he was ‘overseeing the de-development and deindustrialisation of a modern country’, and that ‘sanctions are starving to death 6,000 Iraqi infants every month, ignoring the human rights of ordinary Iraqis’.29

The conclusion to the 1991 war also put Iraq under a ‘weapons inspection’ programme, where UN officials would examine military sites in Iraq to make sure that they had no ‘weapons of mass destruction’ (WMDs). The weapons inspection was wholly insincere, and there mainly to keep the issue of Iraqi WMDs in the public eye. Britain’s MI6 had two clandestine programmes, ‘Rockingham’ and ‘Mass Appeal’, which were tasked with manipulating findings from the UN weapons inspection programme to manufacture evidence of WMDs even though the inspectorate’s actual reports were that there were none – they had been destroyed in 1991. An official in Bill Clinton’s administration explained that they counted on British military intelligence to help come up with the pretext for war: ‘we were getting ready for action and we want the Brits to prepare’.30

The final decision to resume large-scale military operations against Iraq came in the wake of Osama bin Laden’s Al Qaeda attack on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon on 11 September 2001. There was no connection between Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein other than that bin Laden had offered to take part in an Arab force against Iraq in 1991. Still, US President George W. Bush asserted that the perpetrators of 9/11 and Saddam Hussein were part of one continuous ‘Axis of Evil’ in his State of the Union address in January 2002. On 6 April 2002 Tony Blair met Bush and committed Britain to support a renewed all-out attack on Iraq.

On 19 February 2002 allied air forces flew 1700 sorties, 504 with cruise missiles in an attempt to ‘shock and awe’ Iraq. A total of 13,000 cluster bombs were dropped by the allies, 2170 by the UK. According to Human Rights Watch:

UK forces caused dozens of casualties when they used ground-launched cluster munitions in and around Basra. A trio of neighbourhoods in the southern part of the city was particularly hard hit. At noon on 23 March, a cluster strike hit Hay al-Munandissin al-Kubra (the engineers district) while Abbas Kadhim was throwing out the garbage. He had severe injuries to his bowel and liver, and a fragment that could not be removed from his heart.

Human Rights Watch went on to say that:

Three hours later, submunitions blanketed the neighbourhood of Mishraq al-Jadid about two and a half kilometres north east. Iyad Jassim Ibrahim, a 26-year old carpenter, was sleeping in the front room of his house when shrapnel injuries caused him to lose consciousness. He later died in surgery. Ten relatives who were sleeping elsewhere in the house suffered shrapnel injuries. Across the street, the cluster strikes injured three children.31

In late March 2003 Britain’s 7th Armoured Brigade fought Iraqi Army 51st Division for control of Basra. Around 500 Iraqis were killed in a tank battle fought by the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards. British losses were 11.

Between 25,000 and 50,000 Iraqis were killed in the initial invasion of Iraq. But that was by no means the end of the conflict in the country. Though the Iraqi Army was effectively defeated in 2003, under allied rule, the country was plunged into a destructive internecine conflict, as well as several rebellions against the allied occupation that cost hundreds of thousands of lives.

Britain supplied a force of 7200 to police Basra from 2003 to 2009. Hundreds of allegations of torture, assassination and ill-treatment have been laid against the British forces, leading to the setting up of a government Iraq Historic Allegations Team. British soldiers were dismayed to find they were to be held personally responsible and prosecuted for actions they had undertaken as part of military operations. A dossier of allegations passed on to the International Criminal Court brought matters to a head. In 2017 a British lawyer who had prepared some of the cases was struck off, accused of manufacturing evidence. Errors in the preparation of some cases were seized upon to undermine the IHAT, which has now been closed down.

Afghanistan: 2001-9

In 1980 the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan and their forces were pinned down by fierce resistance from Afghan fighters – who were supported by American and British special services and $40 billion in aid. Soviet withdrawal left the country in some turmoil, and the Islamist Taliban (‘students’) emerged as the dominant – and fiercely anti-western – force. Saudi Osama bin Laden was one of the ‘Afghan Arabs’ trained by the Pakistani secret services (the ISI) and his ‘Al Qaeda’ group planned the 9/11 attack on New York and the Pentagon from the country. In October 2001 American and British forces attacked the Taliban government in Afghanistan. Under Operation Enduring Freedom B-52 bombers, Lancers (and British cruise missiles) were sent to try to destroy Bin Laden’s Tora Bora hide-out, followed by special forces, rangers and British marines.

Hamid Karzai was chosen as a western-friendly Pashtun at the Bonn Conference in December 2001, before being elected as interim president by tribal leaders the following year. Western strategists were hoping that the International Security Assistance Force could avoid alienating the local population as happened in Iraq – but with little success. The conflict has cost more than 100,000 Afghan lives, of whom two-thirds were Taliban fighters, and the rest government forces or civilians. Two thousand two hundred and seventy-one Americans have been killed in the fighting, and 456 British troops. The British operation within the ISAF is called Operation Herrick (2003-16). In the occupation and the prolonged (and ineffective) handover that followed, British forces were stationed in Helmand Province in the south west of the country between 2006 and 2009.

The British presence in Helmand lacked legitimacy. The British built Camp Bastion and sent troops to the main urban areas, the provincial capital Lashkar Gah (political HQ) and Musa Qala, Sangin, NawZad and Kajaki. As a force they were thinly stretched in an area the size of Wales.

When British forces handed over authority to local chiefs in Musa Qala, those same chiefs later asked the Taliban to enter the town peacefully, without a shot being fired. When the outside world got to hear about Britain’s humiliation, the British Army had to stage an invasion of the town they had only recently abandoned, with a force of 4500 troops after the US Air Force bombed the town. British commander Major-General Graham Binns asked: ‘If 90 per cent of the violence was directed against us, what would happen if we actually stepped back?’32

Later Afghan President Hamid Karzai protested that the British administration of Helmand Province had undermined the government’s authority, ousting the local governor, and worse bribed Taliban militias to garner support. As international relations specialist David Chandler explains: ‘The British policy of appeasing local opposition leaders, through buying their support and allowing the harvesting of opium poppies, has directly undermined the Afghan government.’33

British forces in Helmand were placed in arbitrary authority over people for whom they had no respect. Courts martial gave an insight into the day-to-day relationship. One soldier was found guilty of abusing an Afghan boy because he had pulled the boy’s hand towards his crotch announcing to his fellow soldiers that the boy should ‘touch my special place’. Another soldier admitted to having an Afghan man photographed with a sign which read ‘silly Paki’.

British ambassador Sir Sherard Cowper-Coles wrote that the Afghan War gave the army ‘a raison d’être it had lacked for years and resources on an unprecedented scale’. It is this, the unprecedented availability of resources, he says, that drove the strategy in Helmand and not an ‘objective assessment of the needs of a proper counter-insurgency campaign in the province’ – the point was just to keep the army busy. Since the British withdrawal from Helmand, Taliban forces have again contested the government for authority in Helmand and in 2017, 300 more US marines returned there.

Libya: 2011; Syria: 2018

Of all military interventions, the western coalition attack on Libya in 2011 is the most pointless. British, French and American leaders waged an air war on the government of Muammar Ghadaffi in Tripoli, in apparent support of rebel forces attacking the capital. British ships and aircraft fired Tomahawk missiles at Al Khums naval base and other targets. Defence analyst Mark Curtis explained that:

British air strikes and cruise missile attacks began on 19 March and within the first month of what became a seven-month bombing campaign NATO had flown 2,800 sorties, destroying a third of Qadafi’s military assets, according to NATO. The RAF eventually flew over 3,000 sorties over Libya, damaging or destroying 1,000 targets.34

The intervention did lead to the capture and killing of Ghadaffi, but the opposition government that replaced him had no authority and has struggled to fend off attacks by ISIS inspired militia ever since. As emerged later, the National Transitional Council, and the Libyan National Army that were recruited with British and American support, were substantially infiltrated by supporters of Islamic State. Conservative minister Alistair Burt conceded that the British security services had been meeting with ‘former members of Libyan Islamic Fighting Group and 17 February Martyrs Brigade’ in 2011. The allied attack was a show of strength, but one that only succeeded in undermining what plausible government existed in Libya and giving succour to militant Islamists.

Around the same time the US and British military were giving support to oppositionists challenging Syrian president Bashar al-Assad’s regime. The Assad dictatorship was deeply unpopular and seemed a likely target for the kind of ‘Arab Spring’ protests to western analysts. Large protests were attacked by state forces leading to a situation close to civil war.

US and British special forces gave assistance to opposition militias, in particular the ‘Free Syrian Army’, which British military advisors helped to train in camps in Jordan. Britain also financed a public relations campaign for the oppositionists paying out £2.4 million. In 2012, the British military were claiming to be at the forefront of arming anti-Assad rebels, and helped President Obama’s team to organise a 3000-ton arms airlift to opposition forces. However, as the leading Liberal Democrat Paddy Ashdown explained, those weapons were ‘going almost exclusively to the more jihadist groups’.35 In 2014 the Free Syrian Army joined with Islamic Front in an attempt to wrest control of Aleppo from Assad’s forces.

In 2015 Russian forces joined the war on the side of the Assad regime, with air attacks that severely undermined the opposition, whether Islamist or moderate. Russian victories put pressure on the US-British policy in the region, and in 2018 after an alleged chemical attack by Syrian forces on the town of Douma, Britain, France and the US launched an air bombardment on government positions. Four Royal Air Force Tornado fighters and four Eurofighter Typhoon fighters fired Storm Shadow missiles at Syrian targets. The Royal Navy’s air-defence destroyer HMS Duncan gave cover. In the bombardment the Barzah scientific research centre was severely damaged, along with two military bases. Just months before the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons had visited Barzah and declared that there were none there. The April 2018 airstrikes have been widely condemned since as gesture politics without any discernible strategic, let alone humanitarian, objective.