In this chapter, we present an overview of the file system formats supported by Windows. We then describe the types of file system drivers and their basic operation, including how they interact with other system components, such as the memory manager and the cache manager. Following that is a description of how to use Process Monitor from Windows Sysinternals (at http://www.microsoft.com/technet/sysinternals) to troubleshoot a wide variety of file system access problems.

In the balance of the chapter, we first describe the Common Log File System (CLFS), a transactional logging virtual file system implemented on the native Windows file system format, NTFS. Then we focus on the on-disk layout of NTFS and its advanced features, such as compression, recoverability, quotas, symbolic links, transactions (which use the services provided by CLFS), and encryption.

To fully understand this chapter, you should be familiar with the terminology introduced in Chapter 9, including the terms volume and partition. You’ll also need to be acquainted with these additional terms:

Sectors are hardware-addressable blocks on a storage medium. Hard disks usually define a 512-byte sector size, but they are moving to 4,096-byte sectors. (See Chapter 9.) Thus, if the sector size is 512 bytes and the operating system wants to modify the 632nd byte on a disk, it must write a 512-byte block of data to the second sector on the disk.

File system formats define the way that file data is stored on storage media, and they affect a file system’s features. For example, a format that doesn’t allow user permissions to be associated with files and directories can’t support security. A file system format can also impose limits on the sizes of files and storage devices that the file system supports. Finally, some file system formats efficiently implement support for either large or small files or for large or small disks. NTFS and exFAT are examples of file system formats that offer a different set of features and usage scenarios.

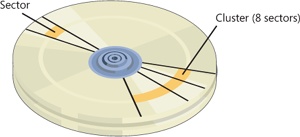

Clusters are the addressable blocks that many file system formats use. Cluster size is always a multiple of the sector size, as shown in Figure 12-1. File system formats use clusters to manage disk space more efficiently; a cluster size that is larger than the sector size divides a disk into more manageable blocks. The potential trade-off of a larger cluster size is wasted disk space, or internal fragmentation, that results when file sizes aren’t exact multiples of the cluster size.

Metadata is data stored on a volume in support of file system format management. It isn’t typically made accessible to applications. Metadata includes the data that defines the placement of files and directories on a volume, for example.