1

A FIREBALL OVER AUSTRALIA

In the summer of 1981, a small black stone wrapped in aluminum foil changed the course of my life. About the size of a marble and indistinguishable from any other rock that might be found on a beach, this stone had traveled from southeastern Australia to NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California, where researcher Sherwood Chang showed me the specimen and gave me a small sample to test. But the stone had traveled even farther. It was a piece of a meteor that had lit up the night sky over the town of Murchison, Australia, in September 1969. The fall began with a bright orange fireball and rolling thunder, followed minutes later by a shower of black stones strewn over five square miles. During the next few weeks, townspeople and scientists collected more than 100 kilograms of meteorites ranging in size from marbles to bricks.

Why would a marble-sized rock be so significant that it can change one's life? The reason is that before traveling 7,000 miles from Australia to California, this tiny bit of rock traveled to Earth from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, a distance of 250 million miles, or even billions of miles if we take into account all of the rock's orbits around the sun before reaching Earth. The rock was produced when a smaller asteroid happened to collide with a larger one, knocking off fragments of the surface and leaving behind a crater resembling those that we can see in photographs of asteroid surfaces (Figure 1).

I held in my hand a genuine rock from outer space. But there was more to this meteorite than just the mineral content typical of other stony meteorites. When the original boulder-sized object exploded over Murchison, the surfaces of the smaller fragments were heated by atmospheric friction to white-hot temperatures. In a few seconds, the friction slowed the fragments from an initial velocity of 20 kilometers per second, and they finally fell to the ground at the same speed they would reach if they were dropped from an airplane. The first stones to be discovered were still emitting a smoky smell from their hot surfaces, a distinctive aroma that I would later notice while extracting organic compounds from the meteorite. Whenever I give talks about this work, I evaporate a drop of Murchison extract into a wine glass and pass it around for audience members to sniff, joking that 4,570,000,000 BCE was a very good year.

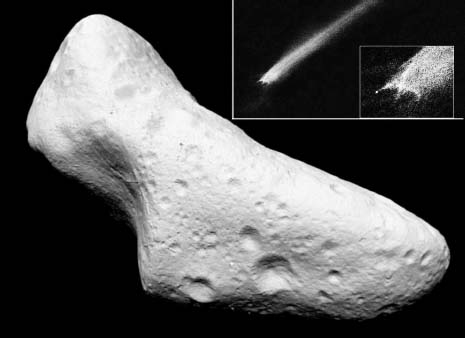

FIGURE 1

The asteroid Eros shows numerous craters resulting from collisions with smaller objects in the asteroid belt. Each impact has the potential to produce fragments of the asteroid surface that can reach Earth as meteorites. The inset shows an actual collision between two asteroids that happened to be photographed, and the shower of fragments can be clearly seen.

That age, 4.57 billion years, is the reason why certain meteorites have changed scientific lives. The Murchison meteorite belongs to a relatively rare group of meteorites called carbonaceous chondrites. Their aroma is produced by organic compounds older than Earth itself, some of which were present in the vast molecular cloud of interstellar dust and gas that gave rise to our solar system 4.57 billion years ago. Most of the organic material—nearly 2% of the total mass of a typical Murchison sample—is in the form of a tarlike polymer called kerogen, but there are also hundreds of different compounds that sound like a chemist's laboratory: oily hydrocarbons, fluorescent polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), organic acids, alcohols, ketones, ureas, purines, simple sugars, phosphonates, sulfonates, and the list goes on. Where did all this stuff come from? Did it have anything to do with the origin of life?

THE MURCHISON METEORITE AND SELF-ASSEMBLY

With a sample of a carbonaceous meteorite in hand, I was ready to do an experiment I had been dreaming about. Ten years earlier, shortly after the Murchison event, Keith Kvenvolden and a group of researchers at NASA Ames had analyzed a sample of the meteorite and convincingly demonstrated that amino acids, one of the essential organic compounds composing all life on Earth, were present in the meteorite. And these were not just the kinds of amino acids found on Earth (which might have been contamination), but more than 70 other kinds that were clearly alien to biology as we know it. This study, and many that followed, established that amino acids, the fundamental building blocks of proteins, can be synthesized by a nonbiological process. From this, it seems reasonable to think that amino acids, at least, would have been available on prebiotic Earth.

I had spent much of my earlier research career studying lipids, which, along with proteins, nucleic acids, and carbohydrates, represent the four major kinds of molecules that compose living organisms. “Lipid” is a catch-all word for compounds like fat, cholesterol, and lecithin that are soluble in organic solvents. In earlier research I had extracted triglycerides (fat) from the livers of rats, phospholipids such as lecithin from egg yolks, and chlorophyll from spinach leaves. All of these procedures used an organic solvent mixture of chloroform and methanol to dissolve the lipids, and I wanted to try the same thing with the Murchison material. The surface of the meteorite certainly had surface contamination from being exposed to the laboratory atmosphere, so I broke it into smaller pieces and carefully obtained an interior sample weighing about 1 gram. Then I ground the sample in a clean mortar and pestle with a mixture of chloroform and methanol as the solvent, and decanted the clear solvent from the heavier black mineral powder. The chloroform solvent had a yellow tint, which meant that it had dissolved some of the organic material in the meteorite. I dried a drop of the solution on a microscope slide, added water, and then examined it at 400 X magnification. It was an extraordinary sight. Lipidlike molecules had been extracted from the meteorite and were assembling into cell-sized membranous vesicles resembling microscopic soap bubbles (Figure 2). Could it be that similar compartments were present when the first liquid water appeared on Earth more than four billion years ago? Maybe, just maybe, if we studied the Murchison meteorite we might know what kinds of molecules made up the membranous boundaries of the first cellular life.

But a huge question remained: Where did the stuff come from? For that matter, where does anything come from? To set the stage for telling that story, let's begin with stars, where everything begins.

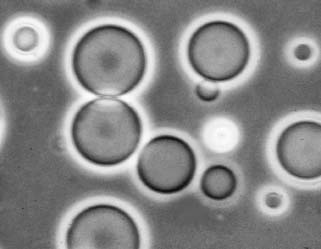

FIGURE 2

Cell-sized vesicles form by self-assembly of lipid-like compounds extracted from the Murchison meteorite.

WHERE DOES EVERYTHING COME FROM? THE LIFE AND DEATH OF STARS

Forty years ago, when a boulder-sized meteorite blazed through the skies above Murchison, Australia, we had only a few speculations about when our universe began and how galaxies, stars, and planets come to be. Now, within a single lifetime, we have definite answers to fundamental questions that have been pondered throughout recorded history. The first hint of such an answer was put forward in 1946 by Fred Hoyle, at the time a young, brash British astronomer. Born in 1915 in Yorkshire, England, Hoyle displayed a creative genius that is a wonderful example of how ideas become grist for the mill of science, and how bad ideas disappear into dust, while the rare gems of good ideas survive scientific grinding to become touchstones for future generations of scientists. Fred Hoyle was full of ideas and was bold enough to publish them. Here are some examples:

- The fossil archaeopteryx (a small, feathered, birdlike dinosaur) in the British Museum of Natural History is a fake.

- Vast molecular clouds in outer space are loaded with microorganisms which brought the first forms of life to Earth.

- Viruses that cause flu epidemics are brought to Earth when it passes through the tails of comets.

- All the carbon required for life to exist is synthesized in the interior of stars.

- The universe has no beginning or end. The idea that the universe has a beginning is nonsense, and it deserves a silly name: the Big Bang.

- The requirements for the synthesis of carbon are so precise that life could not have accidentally arisen. There must have been an intelligence at work to make it happen.

Of these ideas, only one has survived the experimental and theoretical tests that are characteristic of the scientific enterprise. It is now the consensus that all the carbon circulating throughout the universe, including every carbon atom in your body, was synthesized in extremely hot interiors of dying stars (100 million degrees!) and then blasted out into space when the star reached the end of its lifetime in a nova or supernova explosion. To understand this process, we need to recall a little high school chemistry. All matter is composed of atoms, and all atoms have a tiny nucleus composed of elemental particles called protons and neutrons, which are surrounded by orbital clouds of much lighter electrons. (Protons and neutrons are approximately 1,800 times more massive than electrons.) But in stars, the temperature is so high that the electrons cannot be held in place, so basically, stars like our sun are composed of a gas of naked atomic nuclei, mostly in the form of hydrogen and helium. Hydrogen is the lightest element, with a single proton and no neutrons in its nucleus. Helium is the second lightest element, with two protons and two neutrons in its nucleus, and is the product of the initial hydrogen fusion reaction that makes stars shine. If we could somehow grab a 1-gram sample of the universe and use it to fill a balloon on Earth, the balloon would float away because the visible material in the universe is mostly hydrogen and helium.

What Hoyle brilliantly realized is that, at sufficiently high temperatures, two helium nuclei can fuse to form a nucleus of the lightest metallic element, beryllium, which then fuses with a third helium nucleus to produce carbon. Because three helium nuclei combine to make one carbon, this reaction is called the triple alpha process. (Helium nuclei are also called alpha particles when they are emitted from a radioactive element.)

Hoyle had his revelation about the origin of carbon in 1946, but earlier theoretical models had already shown that if carbon is somehow made available, nitrogen and oxygen can be formed in a process called the carbon-nitrogen-oxygen (CNO) cycle, which turns out to be the primary source of fusion energy in large, hot stars on their way to oblivion as novas and supernovas. Descriptions of the CNO cycle were independently published by Carl von Weizsäcker and Hans Bethe in 1938 and 1939. They did not know how the carbon was made, and this is where Hoyle filled in a significant gap in our knowledge a few years later.

Hoyle published his idea in 1946 but did not include a mathematical analysis, although he hinted at it. In 1957, Hoyle joined William Fowler, and Margaret and Geoffrey Burbidge at Cal Tech to publish an article in Reviews of Modern Physics, which became a classic. The article was a brilliant analysis of nucleosynthesis of elements in stellar interiors, and should have won a Nobel Prize for someone. It did, but not for Hoyle. Discovering the treasures hidden in the scientific landscape is a chancy business, but getting credit for your discoveries is even chancier. The Nobel Prize in 1983 went to Fowler, who certainly deserved it for his many contributions, and the prize was shared with Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, who studied stellar evolution. Sir Fred had to be satisfied with a knighthood.

To sum up, we can now account for all the major elements of life in terms of nuclear reactions in stars, a process called stellar nucleosynthesis. The atoms of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and phosphorus that comprise all life on Earth were once in the center of stars more massive than our sun, forged at temperatures hotter than any hydrogen bomb. And what about hydrogen? Even more astonishing, most hydrogen atoms are as old as the universe, which somehow burst into existence 13.7 billion years ago when time began. As living organisms, we are not in any way separate from the rest of the universe. Instead, we simply borrow a tiny fraction of its atoms for a few years and incorporate them into the patterns of life. The hydrogen and oxygen atoms are in the water that flows through our cells, and the carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and phosphorus are linked together in the proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids that are the stuff of life. This is why we call them biogenic elements.

STEADY STATE AND BIG BANG FACE OFF

We have a fair understanding of how the elements of life are made, but what about the universe itself? This story has been told many times, but it is such a good story that I can't resist telling it again. This means that I must first tell you about George Gamow, who has been part of my life for as long as I can remember. As a teenager, all I knew about the person whose name I mispronounced (it's “Gamoff,” not “Gamau”) was that I could actually understand what he wrote about cosmology. A tattered paperback copy of his book One…Two…Three…Infinity! has a place of honor on my library shelf.

Gamow and Hoyle, both energetic personalities, full of good and bad ideas, came to loggerheads over one of the great questions of all time: Did the universe have a beginning? One answer had already been suggested by Monsignor Georges Lemaître, a remarkable Catholic priest whose lifetime (1894-1966) corresponded closely with Gamow's (1904-1968). In 1931, Lemaître published a paper in Nature in which he proposed that the universe was expanding, and must therefore have begun as a “primitive atom.” This was not just an idea but was based on a substantial mathematical foundation. When Albert Einstein met Lemaître a few years later, he told the priest, “Your calculations are correct, but your physics is abominable.”

Lemaître was vindicated two years later when Edwin Hubble presented direct evidence that the light from distant galaxies had a longer wavelength than nearby galaxies, a phenomenon called the red shift. Hubble's observation led to a revelation about our universe, so it deserves a bit of explanation to underline its significance. The simplest way to understand the red shift is by analogy to sound produced by a vibrating structure. Sound travels through air as a vibration of a certain frequency, with lower tones having lower frequencies measured as vibrations per second. For instance, the note A in the middle of a piano keyboard vibrates 440 times per second. Light also has wavelike properties, but its frequency is a trillion times that of sound. The thing to keep in mind is that red light has a lower frequency than blue light.

Most of us have stood near a road when a car passes with its horn blaring. We hear a higher horn tone when the car is approaching, then lower in tone after it passes. This is called the Doppler effect, in honor of Christian Doppler, who first proposed an explanation in 1842. Now imagine that the car passes by at nearly the speed of light, and that we are seeing the headlights rather than listening to the horn. As the car approaches, the headlights would look blue, and as it speeds away from us, they would look redder. This is the effect that Hubble observed, now called the red shift. The most plausible explanation is that galaxies are moving away from us and that the farthest objects have the greatest apparent velocities, some in fact approaching the speed of light.

Gamow loved the idea of an expanding universe. In 1948, he published a superb paper with his student Ralph Alpher entitled “The Origin of Chemical Elements.” The main point of the paper is that hydrogen and helium compose most of the matter of the universe, and they are present in a certain ratio: 92% hydrogen to 8% helium, in terms of the number of atoms. Gamow also included in the paper an important prediction: When it popped into existence, the universe must have been very hot, hotter than the hottest stars today. But with the passage of time, and the expansion of the universe, the cosmic temperature must decrease, just as a compressed gas cools off when it is allowed to expand. Gamow predicted that if we could somehow listen to the universe, we should still be able to “hear” this energy as a kind of low rumble of radio waves.

When he submitted the paper for publication, Gamow could not resist adding the name of his friend and colleague Hans Bethe, who had nothing to do with the work. Gamow expected his joke to be caught before publication, but no one noticed. The paper was published in Physical Reviews, appropriately on April 1, 1948, and the authors listed were Alpher, Bethe, and Gamow. If you don't get Gamow's joke, don't feel bad, because his editor and peer reviewers—all professional physicists—missed it, too. The first three letters of the Greek alphabet are alpha, beta, and gamma, which also refer to the primary particles released by radioactive decay.

Hoyle did not agree that the universe had a beginning. In 1948, he published an alternative hypothesis with his colleagues Hermann Bondi and Thomas Gold, which came to be known as the steady state theory. Perhaps the universe was expanding, they reasoned, but instead of beginning as Lemaître's primitive atom, matter was continuously created out of a hypothetical source of energy to replace the matter lost to expansion, thereby maintaining the steady state we seem to observe today. Hoyle ridiculed Gamow's ideas, referring to them in jest during a radio show as the “Big Bang.” The name stuck.

The opposing ideas of Hoyle and Gamow are an example of science at its best, when two alternative hypotheses are available for testing. The influential philosopher of science, Karl Popper, proposed that even the most creative ideas cannot be classified as science unless they are “falsifiable,” or testable by experiment or observation. In 1962, Thomas Kuhn wrote a book called The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, in which he proposed that on rare, exciting occasions, the accumulation of such evidence will cause one paradigm, or consensus view, to crumble while an alternative paradigm rises to take its place. The goal, then, is to find a critical experiment, usually in the form of a prediction, that will permit us to choose between alternative hypotheses. Sometimes this happens by an accidental observation that we call serendipity, after the folk tale about the three princes of Serendip (an old name for Sri Lanka) who constantly found things by accident that happily fulfilled a future need. In the case of the universe, it was two Bell Labs scientists who stumbled across the answer, and a Princeton physicist who recognized the significance of their discovery.

The prediction had already been made in Gamow's 1948 paper, which was also independently proposed by Yakov Zel'dovich working in Russia, but not much attention was paid to it until Robert Dicke at Princeton had a similar idea. In 1964, two other faculty members at Princeton, David Wilkinson and Peter Roll, began to construct an antenna and amplifier specifically designed to look for cosmic background radiation, which was predicted to exist as a consequence of the explosive birth of the universe. That is, if the Big Bang idea was correct, the energy level of the universe was expected to have cooled to a temperature just a few degrees above absolute zero, a temperature that could be detected as a specific radio frequency in the microwave region of the radio spectrum. By a remarkable coincidence, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson at the Bell Labs were testing a similar instrument that was originally used for bouncing radio waves off satellites. It worked, but there was a strange problem. No matter what direction in the sky they pointed the long metal horn that collected radio waves, it picked up a microwave radiation equivalent to a temperature just a few degrees above absolute zero. This was crazy! Penzias and Wilson had expected to see a certain amount of noise from a variety of sources, and had adjusted their instrument so that ordinary radio waves and errant radar pulses were tuned out. They cooled the receiver with liquid helium, and even cleaned out pigeon droppings that had been deposited in the metal horn over the years. Then they happened to hear about a paper being written (but not yet published) by Dicke and his associates in which it was made clear that a suitable detector should be able to hear the cosmic microwave background, now abbreviated CMB. Penzias and Wilson had inadvertently constructed just such an instrument, and they suddenly realized the importance of their result. Penzias called Dicke and invited him to drive 40 miles from Princeton to the Crawford Hill Bell Labs and literally listen to the CMB, which they could hear as a kind of rumbling static in their headphones.

Everything fit. In a nice example of scientific generosity, in 1965 the two groups published joint papers in the Astrophysical Journal. The first was authored by Dicke, Peebles, Roll and Wilkinson, and outlined the theoretical background of the prediction. The second paper described the detection of the CMB by Penzias and Wilson, for which they were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1978.

With an actual measurement of the predicted CMB, Hoyle's steady state hypothesis had been refuted, and the Big Bang hypothesis became an accepted theory. Gamow must have relished the shift in his favor, but he lived for only three more years. He spent his last years as a faculty member at the University of Colorado, dying in 1968 from liver disease. Gamow Tower at the Boulder campus is a memorial to his time there. But, like Sir Fred, Gamow was never honored with a Nobel Prize. Michio Kaku, a theoretical physicist best known for his contributions to string theory (the “theory of everything”) and his radio show Explorations, once commented that Gamow's willingness to write children's books, like the one that had fascinated me as a teenager, probably influenced the Swedish committee members who choose Nobelists every year. Kaku wrote that “people could not take him seriously when he and his colleagues proposed that there should be a cosmic background radiation, which we now know to be one of the greatest discoveries of 20th-century physics.”

HOYLE, WICKRAMASINGHE, AND PANSPERMIA

Hoyle lived on another 35 years. Although he was never able to match his earlier triumph of carbon nucleosynthesis, he certainly tried. Together with his colleague Chandra Wickramasinghe, now at Cardiff University in Wales, Hoyle coauthored a series of books and papers in which they speculated about how life could have begun on the Earth. The most widely accepted hypothesis is that life began as a chance event in which just the right mix of organic compounds was acted upon by an energy source so that growth and reproduction could occur. The earliest life would not resemble today's highly evolved version, but more likely it was a kind of scaffold that had the essential properties of life. The scaffold was then left behind when more efficient living systems evolved.Hoyle and Wickramasinghe did not subscribe to this view. Instead, they elaborated an older idea championed in 1903 by Svante Arrhenius, the great Swedish chemist. Known as panspermia, this idea proposes that life exists everywhere in the universe and that life began on Earth when frozen extraterrestrial bacteria or spores, drifting as interstellar dust through the galaxy, happened to land here four billion years ago and found it to be habitable. Hoyle took it a step further when he claimed that this was still happening, that epidemics such as the flu pandemic of 1918 were actually caused by extraterrestrial organisms in the tails of comets.

I once met Wickramasinghe in 1986 at the Tidbinbilla radio telescope observatory near Canberra, Australia, and asked whether he and Hoyle really thought that interstellar space was infested with bacteria. He was quite certain of it, he said, noting that the infrared spectrum of interstellar dust closely matched that of dried, frozen bacteria. I mentioned that I was working with the astronomer Lou Allamandola at NASA Ames Research Center, who had demonstrated that the infrared spectrum could be reproduced by ordinary compounds called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). This seemed a much more plausible explanation than a galaxy full of bacteria. Wickramasinghe had a ready retort: “It is up to you to prove that they are not bacteria.”

I have found that a few of my colleagues are not swayed by plausibility arguments, or Occam's Razor and the weight of evidence. In general, scientists are like investors, but instead of money, they invest time—limited to roughly 40 years of active research. Scientists are continuously making judgment calls to decide how to invest their time. They hope their investment will be profitable, not necessarily in monetary terms (that rarely happens) but rather in revealing significant new knowledge. A few scientists spend their lives seeking unusual explanations that others would immediately discard as implausible. Some of my colleagues avoid interacting with these mavericks, but I enjoy listening and reacting to their ideas. Most often the ideas turn out to be not just implausible but wrong. Yet once in a while, a wild idea is beautifully, wonderfully correct. George Gamow had one such idea, and later in this book, I will tell you about Peter Mitchell, another maverick whose implausible idea taught us how metabolic energy is captured in ATP in all life today.

STARS, DUST, AND SOLAR SYSTEMS

The current consensus regarding the time scale of events following the beginning of our universe represents an absolute revelation in the history of science, made possible only when we had a mix of data from radio astronomy and images from the orbiting Hubble Space Telescope that captures light from galaxies at the edge of the visible universe, light that is over 12 billion years old. Using this data, and applying well-established laws of physics, cosmologists can conceive internally consistent scenarios of events that occurred within the first second, minute, hour, and day after the Big Bang, and then the billions of years that followed. The most recent surprise is that the universe seems to consist mostly of “dark matter” and “dark energy” with ordinary matter comprising only a small fraction of its mass—just 4% by one estimate. Furthermore, the expansion is not slowing down, as might be expected, but instead is speeding up. We still have much to learn about the universe we live in, a universe so remarkable that its laws allow life to begin on a tiny planet circling an ordinary star, then to evolve into conscious human beings who can wonder where it all came from.What in this model is relevant to the origin and distribution of life? One thing to realize is that there were no stars for the first 400 million years. The hydrogen fusion reactions necessary for stars to exist could only begin after the universe had cooled sufficiently for hydrogen to collapse by gravitational attraction into dense structures such as stars. Because the Big Bang distributed hydrogen unevenly, the first stars to form clumped together by the billions into immense galaxies. We call our own galaxy the Milky Way, and the word “galaxy” is in fact derived from the Greek and Latin words for “milk.” If we could view our galaxy from above, we would see not only hundreds of billions of stars, but also dark clouds of dust throughout the spiral arms.

Where does the dust come from? When the first stars and galaxies appeared, close to 13 billion years ago, there was no dust, instead only hydrogen and helium were produced during the Big Bang. There were no planets or solar systems because elements heavier than hydrogen and helium were still buried in the hot nuclear gas composing the first generation of stars. How did they escape? The answer to this question comes from yet another revelation of modern astronomy. Even though stars seem unchanging during a human lifetime, on the immense time scale of the universe, stars burn for millions or billions of years and then die in spectacular explosions called novas or supernovas. This is how the heavier elements produced in the first generation of stars escaped into space, finally becoming available to form new stars and solar systems.

In 1054 CE, Chinese astronomers recorded the appearance of a new star as one of the first observations of a supernova, so bright that it shone even during the day. It disappeared after a few weeks, but 700 years later, Charles Messier discovered something strange in the night sky: not a sharply defined star, not a moving comet, but instead a stationary blur of light. Messier had spent his life using a primitive telescope and made a catalog of anything he saw that was not a star or a comet. This faint, blurry object was the first to be described in his catalog, so it is referred to as Mi. The catalog was published in France in 1774, and 100 years later, telescopes had improved to the point that Mi could be seen as more than a faint blur. An early drawing of it showed a crablike structure, so Mi became known as the Crab Nebula.

Recent images taken by the Hubble orbiting telescope (visual light), the Spitzer orbiting telescope (infrared light), and the Chandra orbiting telescope (X-rays), show this amazing object in multiple colors. (See “Sources and Notes” for Chapter 1 at the end of this book for a collection of Crab Nebula images.) Just in the center you can see a small star, which is all that is left of the original star that was about 10 times more massive than our sun. Now it is an extremely dense ball of neutrons about the size of a small city, spinning 30 times per second and emitting a low-frequency “hum” that is detectable with a radio telescope. We refer to such stars as pulsars because of the pulsing radio waves produced as they spin. Pulsars are not smooth spheres, but instead have a region that sends radio frequency energy into the surrounding space, much as a lighthouse sends a beam of light out from a rotating lamp. If you would like to hear some of these literally unearthly stellar noises, search for “pulsar sounds” on the Internet.

The reddish glow of the Crab Nebula is due to dust particles that are illuminated by its central star. This stardust will later accumulate into vast clouds in the galaxy and give rise to new stars and solar systems, composed of ashes from the Crab and other exploded stars. To give some idea of the scale, the nebula is 6,500 light-years distant and 12 light-years across. Our entire solar system out to the orbit of Pluto is only 10 light-hours across, so approximately 10,000 of our solar systems lined up edge to edge would fit into the diameter of the Crab Nebula.

Supernova explosions are rare. In our galaxy, which contains 400 billion stars, a supernova occurs on average once every 50 years. They are produced by stars larger than our sun that are very hot and rapidly burn through their hydrogen fuel. In contrast, ordinary stars have lifetimes of several billion years, thousands of times longer than the stars that end up as supernovas. A consensus age of the universe is 13.7 billion years, which means that we are only just now seeing a generation or two of ordinary stars reach the end of their 5- to 10-billion-year lifetime. When stars like our sun deplete the hydrogen that fuels their fusion furnace, they swell into enormous, cooler red giants, then collapse to become white dwarfs. Our sun is middle aged, with perhaps five billion years to go, but when its red giant phase begins it will expand as far as the orbit of Mars and the four inner planets of our solar system will become baked cinders.

STARDUST AND THE ORIGIN OF SOLAR SYSTEMS

When a red giant collapses, more than half of the remaining mass is propelled into the interstellar medium, often producing beautiful structures called planetary nebulas that slowly expand from the central star. Observational astronomers seldom have a chance to exercise their imaginations, so whoever first sees such images appearing on his or her photographic plates (or computer screens these days) gets to say what they look like, something like a stellar Rorschach test. Examples include the Ant, the Eskimo, and the Cat's Eye nebulas.These stunning images can be viewed in the Hubble Heritage website (see “Sources and Notes”), and only became possible after the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) was launched into orbit April 24, 1990. We are the first generation of human beings ever to see the true beauty of our galaxy and universe. The Hubble cost $2.5 billion to launch, two dollars per year for every US taxpayer, about what I spend in the morning for an espresso coffee. The return on this modest investment has been an immense expansion of our knowledge about the origin and evolution of the universe we live in. We can also see the structure of molecular clouds in our galaxy and get a glimpse of new stars and solar systems in the process of formation. We can see nearly to the edge of the universe, and the HST has captured perhaps 1,000 distant galaxies in a single image as it peered into the depths of space.

What do supernovas and planetary nebulas have to do with the origins of life? The answer lies in the composition of the material that is ejected during the explosive phase, and what happens to it over time. The basic composition is not very exotic: whatever was in the original star, but cooled down as it expands into space. This includes a mixture of elements in the gas phase, such as hydrogen, helium, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur; simple compounds like water and carbon dioxide; dust particles composed of silica, the same stuff as in sand; and metals like iron and nickel. If this sounds familiar, it should, because it is what Earth—and everything alive on Earth—is made of. Over millions of years, the dust slowly gathers into enormous clumps light-years in diameter, and these clumps give rise to new stars and solar systems.

One such interstellar cloud is called the Rosette Nebula, and magnificent images can be viewed in the Hubble Heritage website (see “Sources and Notes”). Dark dusty clouds are clearly outlined against the background, which is illuminated by a group of young stars that have burst into life. The pressure of their light is blowing away the surrounding dust so that a space has been cleared around the group, leaving a hole in the center of its rosette shape. The Rosette Nebula is about 50 light-years across, 10 times the distance from our solar system to the nearest star, Alpha Centauri. Although the Rosette Nebula is particularly beautiful, the formation of new stars and solar systems occurs throughout our galaxy, wherever nebular clouds of stellar ashes accumulate.

Five billion years ago, our own solar system emerged from a cloud resembling the Rosette Nebula and it is important for our story that we understand how it happened. This brings us to planet formation, and how Earth came to be the way it is. Let's go through the steps in chronological order:

- Clouds of dust and gas ejected from dying stars gather into immense aggregates like the Rosette Nebula.

- Turbulence within a cloud (or sometimes a shock wave from a nearby supernova) causes the local density to increase to the point that gravity takes over and produces dense aggregates of dust and gas called proplyds.

- As the dust and gas collapse inward under the force of gravity, residual rotation within the proplyd speeds up, just as ice skaters spin faster when they pull in their arms.

- The rotating cloud of dust and gas forms what is called a nebular disk, which has a much higher density in its center.

- Material falls into the dense center ever more rapidly, and the heat generated begins to raise the temperature. The protostar begins to glow red.

- The temperature at the center rises to 10 million degrees, and hydrogen fusion begins. The protostar has become a true star.

- But in some cases, not all of the material in the nebular disk falls into the new star. Some of it can remain to form what is called a protoplanetary disk. This material has its own turbulence and rotating local densities, and undergoes smaller versions of gravitational collapse. The result is a series of planets circling the star, each with its own residual rotation.

- In the case of our own solar system, in the first few million years after the sun reached its full status as a new star, its light and solar wind began to exert pressure on the remaining dust and gas of the disk. The material was slowly blown outward, leaving behind four rocky planets, including Earth. But beyond the orbit of Mars, the effects of pressure became negligible so that the planets now called Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune had time to gather the remaining material and become the gas giants we see today.

Although we can never see this process from beginning to end in a single lifetime, the reason the story is so convincing is that with the help of the Hubble Space Telescope, we can now observe solar systems elsewhere in our near galactic neighborhood at various stages of evolution—from dark molecular clouds composed of dust and gas, to new stars, and even to dusty disks around new stars that have indications of planet formation. To this evidence is added the fact that the power of modern computational methods permits us to make in silico models of planet formation. In these simulations, thousands of small particles are inserted into a spinning disk around a star, and the computer program keeps track of what happens to the particles according to Newtonian laws of physics. In other words, each particle has a certain mass that exerts a gravitational force on other nearby particles, and each particle also has a velocity as it moves within the slowly spinning disk. In this way, the interactions within the disk can be followed over millions of years of virtual time.

In one such simulation, small aggregates of particles can be seen gathering into larger lumps, which ultimately grow into planetesimals ranging in size from a few kilometers to hundreds of kilometers in diameter. Due to disturbances caused by Jupiter's gravity, the asteroids in orbit between Mars and Jupiter stop accreting at this point, and are considered to be the leftovers of the planet-forming process. After objects the size of planetesimals appear, planet formation can begin in earnest. The vast numbers of planetesimals are in wildly chaotic orbits that frequently produce collisions, and each collision results in a larger body and showers of smaller fragments. In just a few million simulated years, the primary accretion is completed, leaving planets of variable size orbiting the central star. Most of the original planetesimals are swept up by the planets, and any remaining dust is driven into the outer solar system by the light and stellar wind of atomic particles emitted by the newborn star. (See “Sources and Notes” for more information about this simulation.)

WORLDS IN COLLISION: THE EARTH-MOON SYSTEM

The consensus view is that our own solar system originated in this way. However, there is one last event that must be taken into account in relation to the origin of life, which turns out to be the special case of our own planet, Earth. Of all the planets of the solar system, only Earth has an ocean of liquid water, and a moon that is so large in relation to its size. Where did oceans come from? Where did the moon come from? Why is the moon covered in craters produced by the impact of giant asteroid-sized bodies? Was a moon, and the tides it produces, essential for life to begin?

To follow the train of logic that led to the current model, we can first sketch out alternative proposals and show why each is problematic:

- The moon developed independently as a small planet and was captured by the Earth's gravitational field. However, according to Newtonian laws of gravity and motion, it is mathematically impossible for two moving objects to pair up this way.

- The moon is just a piece of Earth that broke away due to centrifugal force. Again, this is physically impossible because Earth's rotational velocity is too slow to generate such forces.

- Earth and its moon congealed as a pair out of the same dust cloud that produced the other planets. The problem here is that Earth has a metallic iron-nickel core, but we can calculate the density of the moon from its known gravity, and it is too light to have an iron core. If Earth and moon formed out of the same material, they should both have metal cores.

- The orbit of a Mars-sized planet (sometimes called Theia after a Greek goddess) happened to intersect the orbit of proto-Earth. The two planets underwent a cataclysmic collision in which the mineral and metallic contents of Theia were added to that of Earth, bringing it up to its present mass. The energy of the collision melted Earth's crust and sent a small fraction of the total mass into orbit, forming a ring of vaporized rock from which the moon congealed by gravitational accretion.

After much debate and argument, the fourth explanation is now the consensus view. The laws of physics can be used to devise a computational model of the process, and one can watch the formation of a simulated Earth-moon system on a computer screen. The clincher is that the model makes predictions about the mineral composition of the moon. When moon rocks were returned during the Apollo series of lunar explorations, laboratory tests of the rocks' mineral content matched the composition predicted if they were produced by a collision of planets.

What does this mean for the origin of life? The main point is that Earth's crust would be turned into molten lava by the energy released during the collision, and no organic compounds could survive this searing temperature. Most of the early atmosphere, including water vapor, would have been blasted out into space. This means that the atmosphere had to be replaced in some way. Furthermore, all the organic compounds required for life to begin needed to be replaced. But what were the sources of water and organics? And what kinds of organic material would be available?

These questions will be addressed in later chapters, but the short answer is that the minerals composing the interior of Earth still had a lot of water and carbon dioxide left over from the original accretion process, and these were continuously brought to the surface by volcanic outgassing. A smaller amount, now estimated to be about one-tenth of all ocean water, was delivered to Earth by impacting comets, which are giant conglomerates of ice and dust containing 60% to 80% water. The two primary sources of organic material were delivery from a continuing infall of comets, meteorites, and dust, and a synthesis of organic compounds by a variety of geochemical reactions.

CONNECTIONS

As a result of the revelations emerging from today's astronomy and cosmology, our understanding of life is no longer confined to the thin layer of Earth's crust called the biosphere. Instead, we have a much expanded narrative that is encompassed by the new field of astrobiology. For instance, we now know that the primary elements required for life are continuously produced by nucleosynthesis in stars. At the end of their lifetimes, when stars run out of hydrogen that supports nuclear fusion reactions, they first expand into red giants and then collapse into white dwarfs. During collapse they explosively eject much of their mass into the interstellar space, where the atoms aggregate into microscopic dust particles of silicate minerals coated by a mixture of ice, carbon dioxide, and organic compounds. The dust accumulates into dense molecular clouds light-years in diameter, and these clouds undergo gravitational collapse to form new stars, a few of which have a dusty nebular disk from which new planets form. Planets are produced by collisions between kilometer-sized aggregates called planetesimals. Sometimes much larger collisions occur, such as the one that produced our own Earth-moon system. The energy of the collision melted Earth's surface and eroded much of the early atmosphere, which was replaced by volcanic outgassing of water and carbon dioxide from Earth's interior. The molten surface cooled rapidly by radiating heat into space, and the water vapor condensed into oceans.

The continuous infall of meteorites, and their composition, strongly supports the conclusion that the elements required for the origin of life were present in the early atmosphere and oceans, together with immense amounts of energy that could drive the synthesis of ever more complex organic compounds. Chapter 2 will describe the environment of early Earth and address the next question: Where could life begin?