3

WHEN DID LIFE BEGIN?

Although we are therefore mightily constrained in our efforts to document, and decipher, the Precambrian history of life, we can take one more step toward understanding—we can make an educated guess. This is not as wild and woolly an exercise as it might first appear because a really good guess might cause us to ask new questions that lead to increased knowledge.

WILLIAM SCHOPF, 1991

Much of what we know about the origins of life is based on educated guesses, but a few things are reasonably certain. For instance, with some confidence I can state that the solar system is 4.57 billion years old, and Earth is about 4.53 billion years old. Easy to say, but how can we know for sure? And why isn't Earth as old as the solar system? The reason we have a certain amount of confidence in such numbers is that over the past century, physicists discovered radioactivity and began to understand how radioactive elements could change into other elements over time. We take this knowledge for granted now, but only in the last 50 years have we discovered how to use natural radioactivity as a precise time-keeping method.

A time interval of four billion years is almost incomprehensible. However, we can get a feeling for what this really means by imagining that time passes at 1,000 years per second. At that rate, all of recorded history would zip by in 5 seconds, and prehistoric cave drawings in France were being made 30 seconds ago, when Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis were still competing for territory. (The Neandertals lost.) Extensive glaciation (ice ages) occurred every 100 seconds, with warmer interglacial periods lasting 30 seconds. (The last ice age ended 11 seconds ago, so enjoy the interglacial warmth while you can.) The first human beings appeared in Africa about 3 minutes ago (200,000 years), and the first human-like primate ancestors about an hour ago (4 million years). Then there is a big jump in time back to the giant impact of a small asteroid that killed off the dinosaurs 18 hours ago (65 million years). Dinosaurs first appeared 200 million years ago and ruled the biosphere for 37 hours of our accelerated time frame. Compare this to the 3 minutes that the humans and their ancestors have been around! But after the giant impact, small, rodent-like mammals had a chance to try their luck, and human beings are the result of that opportunity.

For the next time interval, we need to use days instead of seconds, minutes, and hours. About 7 days back in time we reach the Cambrian Era, 543 million years ago, with the appearance of marine organisms large enough to leave recognizable fossils. Now we can appreciate the largest time span of all, called the Precambrian Era, which goes back to the origin of life. Again in our accelerated time frame, this occurred 43 days ago, equivalent to 3.8 billion years.

For me, at least, this gives a sense of the immense time interval between the origin of life and today's biosphere: 43 days for life to begin and evolve to fill every niche in the biosphere, with just 5 seconds of human history tacked on at the end. Why did it take so long (3 billion years) for single-celled life to evolve into larger multicellular organisms? And after all that time, how could multicellular plants and animals appear so quickly in the evolutionary time scale, about half a billion years ago? There are several reasons, but the availability of oxygen was probably a major factor. Bacteria remained as single cells when light and low-energy chemical reactions were the only energy sources. But photosynthesis by cyanobacteria began to produce oxygen soon after life originated, and little by little, the oxygen accumulated in the atmosphere. When oxygen reached a certain level, about two billion years ago, another kind of bacteria learned to use high-energy oxidative metabolism as an energy source. This fundamental split between cells that use light energy and cells that use oxygen marked the turning point in evolution that eventually led to plants and animals.

A GEOLOGICAL TIME SCALE

Scientists don't think about time scales in terms of 1,000 years per second. Instead, we give names to specific time intervals, and after you get them memorized, they become as familiar as a map of your home town. Some of the names refer to specific points in the geological record, and others to specific points in the biological record. For our purposes there are only a few that need to be kept in mind because these are associated with the origin and early evolution of life. The longest time intervals, or eons, are called the Hadean, Archaean, and Proterozoic. Chapter 2 described evidence from ancient zircons that liquid water was present as oceans more than four billion years ago, in the Hadean Eon, and the first faint traces of life appear about 3.8 billion years ago, in the Archaean Eon. Microfossils of bacterial life have been reported in ancient rocks that are 3.5 billion years old, although there is a certain amount of controversy because nonbiological explanations have also been proposed to explain the structures. Unmistakable microfossils of bacteria become abundant in the Proterozoic Eon, which began 2.5 billion years ago.

HOW TO MEASURE 4.5 BILLION YEARS

To get back to the original question, how can we determine the age of something that is several billion years old? One of the most important methods depends on a remarkable relationship between lead and uranium. There is an interesting history related to these two metallic elements. Uranium the metal and Uranus the planet are both named after the Greek god Uranus, who in mythology ruled the sky. Uranus was the father of Saturn and grandfather of Jupiter, names chosen very appropriately for two other major planets. Uranus was discovered by William Herschel in 1781, and eight years later, Heinrich Klaproth isolated uranium the element, naming it in honor of the new planet. The abbreviation U is obvious, but what about lead and its abbreviation Pb? The metal lead was discovered thousands of years ago, and the word “lead” comes from an early form of the English language. The Latin word for lead is plumbum, from which the word “plumber” and the abbreviation Pb are derived. (Lead is a soft metal that is easily shaped and molded, so it was used in Roman times to make pipes for plumbing.)

There is more to the story, which shows how major advances in science are often revealed by a chance observation. In 1896, the French scientist Antoine Henri Becquerel was trying to figure out why certain minerals were phosphorescent (glowing in the dark after exposure to bright light). He thought it might have something to do with X-rays, which had recently been discovered. X-rays were able to penetrate opaque materials and produce an image on film, so Becquerel wrapped photographic plates in black paper and placed different phosphorescent minerals on them for several days. When he later developed the plates, all but one of the plates were completely blank. The exception was the plate exposed to a mineral containing uranium, and Becquerel was astonished to find that an unknown form of energy had penetrated the black paper and produced a smudgy image where the uranium ore had been placed.

This is an example of how a single scientific observation can change the course of human history, both for better and for worse. The penetrating energy attracted the interest of other scientists, including a young Polish woman named Marie Sklodowska, who was fascinated by physics. It was impossible at the time for a woman to get an advanced degree in Poland, so she enrolled at the Sorbonne University in Paris. Marie had heard about Becquerel's results, and she decided to isolate the mysterious component that produced the effect. During the course of her studies, one of Marie's professors, Pierre Curie, noticed her deep intellect and caring personality. Marie, in turn, was impressed by his passion for science. As is said today, they were soul mates. After only a few meetings, Pierre wrote to Marie asking her to marry him:

It would, nevertheless, be a beautiful thing in which I hardly dare believe, to pass through life together hypnotized in our dreams: your dream for your country; our dream for humanity; our dream for science. Of all these dreams, I believe the last, alone, is legitimate. I mean to say by this that we are powerless to change the social order. Even if this were not true we should not know what to do…. From the point of view of science, on the contrary, we can pretend to accomplish something. The territory here is more solid and obvious, and however small it is, it is truly in our possession.

So Marie Sklodowska became Marie Curie, and together the young couple went on to isolate the radioactive elements polonium and radium. Marie, in fact, invented the term radioactivity to describe their unique properties. To honor their discoveries, in 1903, the Curies were the first husband-and-wife team to be awarded Nobel Prizes.

The Curies isolated tiny amounts of polonium and radium from many kilograms of an ore called pitchblende, but the major radioactive component of pitchblende is uranium. Many tons of uranium have now been produced by extraction from pitchplende, and the metal has a number of uses other than in nuclear reactors for power generation. For instance, on a shelf in my lab sits a small glass bottle filled with a yellow powder, uranium acetate, that we use to stain biological materials to be examined by electron microscopy. The uranium acetate is mostly composed of the uranium isotope U238, which is present virtually everywhere in Earth's mineral crust. But if I take off the lid and hold a radiation counter above the powder, the buzz from the speaker tells me that the powder is weakly radioactive. Uranium metal is the heaviest naturally occurring element, with 92 protons in its nucleus, and as many electrons in orbit around the nucleus. The technical abbreviation is 92U238. The 92 is the atomic number (92 protons in the uranium nucleus) and 238 is the atomic weight (92 protons added to 146 neutrons in the nucleus). U238 composes 99.3% of natural uranium, while U235 (143 neutrons) is about 0.7%.

The main properties of elements are associated with their atomic number, but like uranium, most elements can have different atomic weights due to varying numbers of neutrons. The atomic weight defines an isotope of the element, and often one of the isotopes is radioactive. For instance, there are two natural isotopes of hydrogen in water (H2O). The first is ordinary hydrogen with a single proton and no neutrons in its nucleus, and the second is called deuterium, which has both a proton and a neutron in its nucleus. There is also a radioactive isotope of hydrogen called tritium, which has two neutrons in its nucleus, but this is made artificially in a nuclear reactor. Another example is carbon, in which the most common isotope is C12, followed by C13, with one extra neutron. There is also a radioactive isotope of carbon with two extra neutrons—C14—which can be used to determine the age of organic, carbon-containing material.

Uranium is surprisingly abundant in Earth's crust—in the same range as tin, mercury, and arsenic. It is common knowledge that if enough U235 can be gathered together in one place (about 7 kilograms, the size of a tennis ball), a chain reaction occurs that releases a fraction of the stored energy according to Einstein's famous equation: E = mc2. If the energy is released slowly under controlled conditions, it is available as useful heat in a nuclear reactor. If it is released in a few milliseconds, it produces the massive explosion of an atomic bomb.

The isotope U238 cannot sustain a chain reaction, but still undergoes radioactive decay at a certain, very slow rate. If a sample of pure U238 metal could somehow be analyzed 4.47 billion years later, precisely half of the U238 would have turned into an isotope of lead (Pb206). U235 undergoes radioactive decay about six times faster so that a sample of pure U235 would only take 704 million years for half of it to turn into a second lead isotope (Pb207) by radioactive decay. This time interval is called the half-life, and is one of the most important ways to establish the age of the solar system and Earth.

THE URANIUM-LEAD CLOCK

How do we determine ancient age by measuring uranium and lead composition? The actual technique is moderately complicated because it involves a method called mass spectrometry. This method allows us to separate all of the isotopes of uranium and lead that are present, plug the results into an equation, then solve the equation to get the age of the sample. But to put it simply, if I knew that a mineral started out long ago with pure U238 in it and then determined that the amount of lead in the mineral equaled the amount of uranium, I could conclude that the mineral was 4.47 billion years old. Small amounts of lead are everywhere, so we need to start off with something that contains only pure uranium. It was discovered that zircon, the same mineral that led us to determine that oceans were present over four billion years ago, can incorporate uranium atoms, but not lead atoms into its crystal structure. This means that if we isolate a zircon from a mixture that we want to date, we can assume that only uranium was present when the zircon formed, and that lead atoms would be the result of radioactive decay of U238 and U235.

What samples should we analyze with this powerful technique? Why not try to find the oldest rocks on Earth? Earth has undergone extensive geological changes since its birth as a planet, as new continental crust emerged from the underlying mantle and floated on the relatively fluid rock beneath. The continents today are relatively recent features. If you could view a map of the continents only 200 million years ago, when dinosaurs ruled Earth, most of the land mass would comprise a single supercontinent called Pangaea. Over the ensuing millennia, Pangaea separated into a series of plates that support continents today. We also know that new ocean floor forms by an upwelling of magma through a series of cracks in the sea floor that then dives back down by subduction at the edges of continents. The cracks produce the hydrothermal vents described in the previous chapter, and the subduction process along the edges of continents also permits molten magma to reach the surface to produce volcanoes. The Pacific “Ring of Fire,” which runs along the coasts of North and South America, extends through Alaska, and then stretches down through Kamchatka, Japan, and Indonesia, is the best known example of volcanism due to subduction.

As a result of tectonic turnover, most of Earth's original crust has disappeared in the past four billion years. Fortunately for geologists, tiny remnants remain in Greenland and northern Canada, in parts of South Africa, and in Western Australia. In 2003, John Valley, a geologist at the University of Wisconsin, traveled to Australia with a team of his students and took samples from a group of rocks that had already been dated by the uranium-lead method at 3.4 billion years old. The rocks, like many such geological formations, were produced from a conglomerate of mineral components that had been mixed by erosion into a thick layer. John's team toted many kilograms of sample material back to their laboratory and laboriously ground the samples into a coarse powder. Then they sorted through the material with a microscope, looking for rare zircons the size of pinheads.

The next step was to examine each zircon with an instrument called an ion microprobe. In this device, a beam of high-energy ions, such as cesium, is directed onto the surface of the mineral so that the component atoms are knocked off into the vacuum. The atoms gain an electrical charge during this process and are called secondary ions. At first, they are a mixture of all the atoms in the sample, including trace amounts of uranium and lead, as well as oxygen isotopes having atomic weights of 16, 17, and 18. The ions are captured by a strong electrical voltage and sent down a column where they pass through a magnetic field that separates them according to their atomic mass. Heavy atoms like uranium and lead are only slightly affected by the magnetic field, but because uranium isotopes (U238 and U235) are heavier than lead (Pb206 and Pb207), all four isotopes are separated and appear as four peaks in the readout from the instrument. The oxygen isotopes are much lighter and more strongly affected by the magnetic field, but they also produce three distinct peaks. The relative heights of the uranium and lead peaks are used to calculate the age of the zircon, and the oxygen peaks are used to deduce the temperature at which the zircon was formed.

John Valley and his students were astonished when the results of their calculations first popped up on their computer screens. The zircon was 4.4 billion years old, the oldest mineral yet discovered, nearly as old as Earth itself. Furthermore, the oxygen isotope composition of the zircon indicated that it had not formed at volcanic temperatures, but instead at much lower temperatures consistent with the presence of water.

METEORITES AND THE AGE OF THE SOLAR SYSTEM

In a sealed glass container in my lab, I keep a collection of perhaps a dozen meteorite samples. People who do my kind of science know many meteorite names by heart: Murchison, Murray, Allende, Orguiel, Ivuna, and Tagish Lake. These are famous because they are carbonaceous chondrites, a name derived from the fact that they contain organic carbon compounds mixed in with microscopic particles of silicate minerals. Also scattered throughout the black mineral matrix of these meteorites are white pebbles called chondrules. These were produced when the sun first began to produce heat and light. The heat melted aggregates of dust particles, which then fused into chondrules.

Carbonaceous chondrites, along with comets, are samples of the most primitive components present in the early solar system. Other meteorites in my collection are protected in small, stainless steel containers with tightly fitting lids. These are pieces of meteorites found in Antarctica, also carbonaceous chondrites. There is one special container in the collection, and when we have visitors to the lab I shake the container to make the contents rattle. “Hear that?” I ask. “That's a piece of the planet Mars.” And it really is. It is a 1-gram sample of the Nahkla meteorite that fell in Egypt in 1906, which was carefully divided into portions and made available to researchers. There are only a few meteorites known to originate on Mars, called SNC meteorites from the first initials of the places where the first three were found. (The N stands for Nahkla, for instance.) We know they are not ordinary meteorites because their mineral composition is what one would expect of a planetary surface, rather than the asteroids where most meteorites originate. The most convincing evidence that the SNC meteorites are from Mars is that they still contain gas, and when this gas is analyzed, it closely matches the atmospheric gas composition of Mars.

The oldest zircons found in terrestrial rocks give evidence that they were produced 4.4 billion years ago, yet we said that the actual age of Earth is 4.53 billion years, and the solar system assembled from a nebular disk 4.57 billion years ago. Where do those numbers come from? The age of the solar system is determined by assuming that asteroids are leftovers from the original accretion process. As described in Chapter 1, meteorites are chunks of asteroids that have constant traffic collisions with other asteroids so that fragments of their surfaces are knocked off into space. A tiny fraction of the pieces happens to intersect with Earth's orbit around the sun. The meteors, or “shooting stars,” we see at night are produced by particles the size of sand grains, mostly the dusty remains that comets shed as they pass through the inner solar system. The word “meteor” comes from a Greek word describing aerial phenomena, so meteorology is the study of weather, and a meteor is simply something that happens in the sky. Shooting stars are common, sometimes arriving as showers like the Leonids or Perseids that occur regularly every year. More rarely, a chunk of material ranging in size from a golf ball to a small boulder enters the atmosphere and becomes a fireball as it burns up in the atmosphere in a few seconds. Fragments of the original object that survive the fireball and reach the ground are called meteorites.

About once a century, a much larger object enters the atmosphere and releases energy equivalent to the explosion of a nuclear weapon. One such event occurred in 1908 over Tunguska, Siberia. There is no crater, so the Tunguska explosion was produced by a large chunk of relatively fragile material similar to the Murchison meteorite that entered the atmosphere and exploded before it reached the ground. The explosion over Tunguska produced a massive shock wave, a pulse of sonic energy that traveled downward and leveled 1,000 square miles of forest. Here is an account recorded in 1926 by one of the first scientists to visit the remote area, who interviewed an eyewitness living about 40 miles south of the impact site:

At breakfast time I was sitting by the house at Vanavara trading post facing North. I suddenly saw that directly to the North, over Onkoul's Tunguska road, the sky split in two and fire appeared high and wide over the forest. The split in the sky grew larger, and the entire Northern side was covered with fire. At that moment I became so hot that I couldn't bear it, as if my shirt was on fire; from the northern side, where the fire was, came strong heat. I wanted to tear off my shirt and throw it down, but then the sky shut closed, and a strong thump sounded, and I was thrown a few yards. I lost my senses for a moment, but then my wife ran out and led me to the house. After that such noise came, as if rocks were falling or cannons were firing, the earth shook, and when I was on the ground, I pressed my head down, fearing rocks would smash it. When the sky opened up, hot wind raced between the houses, like from cannons, which left traces in the ground like pathways, and it damaged some crops. Later we saw that many windows were shattered, and in the barn a part of the iron lock snapped.

Every 100,000 years or so, something even larger plows through Earth's atmosphere in a few seconds and delivers enough energy to produce a gaping crater resembling those we see on the lunar landscape. The most recent of these crashed into the Arizona desert about 50,000 years ago. Traveling at 13 kilometers per second, it produced a crater more than 1 kilometer in diameter and 150 meters deep. The energy of the explosion is estimated to be 150 times greater than that of the atomic bomb tested in July 1945 at the Trinity Site near Alamogordo, New Mexico. When the crater was first discovered in Arizona, no one knew what had caused this weird geological feature, so it was named the Canyon Diablo Crater after a small nearby canyon, and it was generally believed to be the result of some kind of volcanic eruption. But in 1903, a mining engineer named Daniel Barringer looked at all the fragments of iron scattered around the crater and correctly concluded that it was the result of a meteorite impact. In scientific literature, it is now called the Barringer Crater in honor of the engineer's good guess, and when you drive by the site on the way to nearby Flagstaff, you will see a road called Meteor Crater that leads to the privately owned tourist attraction.

In the early 1950s, Clair (Pat) Patterson, a Cal Tech geochemist, realized that the particular composition of the iron and lead minerals in Barringer Crater provided a way to estimate its age with remarkable accuracy. The age was determined from uranium-lead isotopes, and in 1956, Patterson published a paper in which he convincingly showed that the fragments were 4.55 billion years old. Since that time, hundreds of estimated ages of other meteorites have been determined, with ages ranging from 4.53 to 4.58 billion years. This range does not arise from experimental error, but instead reflects the fact that the parent bodies of the meteorites must have formed at slightly different times in the early solar system's history. To summarize, the oldest rocks on Earth are zircons, and their uranium-to-lead age is 4.53 billion years. The current scientific consensus is that the age of the Barringer meteorite represents a reasonable estimate of the age of the solar system, slightly older than Earth at 4.57 billion years. Given those numbers, we have a context for attempting to give a date to the origin of life, but first we need to describe how giant impacts in the Hadean Eon were likely to have affected the actual time that life could begin.

LIFE AND THE LATE HEAVY BOMBARDMENT

When a few kilograms of lunar rocks were returned by the Apollo astronauts in the 1970s, geologists were delighted to have actual samples of the moon to study. They found that virtually all of the rocks could be classified as igneous, meaning that they had formed at temperatures of molten magma, but they also found that some of the rocks were obviously pieces of the lunar crust produced by giant impacts of asteroid-sized objects. Anyone with a pair of binoculars can still see the enormous lunar craters that resulted from these impacts. But a puzzle soon arose. When the rocks were dated, they had a range of ages all the way back to 4.5 billion years old, as expected. However, an unexpected abundance of rocks were found with ages around four billion years ago. It was as though something stirred up the solar system during that time interval and sent millions of objects ranging up to hundreds of kilometers in diameter falling toward the sun, where they collided with the inner planets. Some of the craters we see on Mars, Venus, Mercury, and our moon are a permanent record of the bombardment.

Earth could not escape, and the only reason its surface lacks a similar number of craters is that the combination of erosion, plate tectonics, and geological processing has almost completely resurfaced the planet. Nonetheless, there is now a consensus that another bombardment of comets and asteroid-sized objects pelted Earth between 4.1 and 3.8 billion years ago. This period is called the Late Heavy Bombardment (often abbreviated LHB). By extrapolation from the lunar cratering record, it has been estimated that during the LHB, impactors the size of the dinosaur-killer asteroid hit early Earth every 100 years or so. In the same time interval, there were about 40 giant impacts that would have left craters around 1,000 kilometers in diameter, the size of the largest craters on the moon. There would also have been a few impactors that delivered enough energy to produce ocean-sized craters, vaporizing whatever oceans existed at the time and sterilizing Earth's surface. Kevin Maher and David Stevenson at Cal Tech were first to point this out and coined the phrase “impact frustration of the origin of life.” In other words, life could have originated on multiple occasions, but only after the last major impact event would it be able to survive to begin the long evolutionary pathway to life today.

If this scenario is correct, we can predict that the first evidence of life will not be older than 3.8 billion years, just about the time the LHB ended. But obvious fossils did not appear in rocks until the Cambrian explosion three billion years later. What evidence could there possibly be for the existence of life that long ago? This question brings us to the concept of biomarkers and biosignatures, which is also central to our search for possible life on Mars or other habitable planets.

FOSSILS, BIOSIGNATURES, AND BIOMARKERS

Most people are familiar with one kind of biosignature called fossils, which are impressions or mineralized structures in sedimentary rocks that are produced by the hard shells and bones of early animal and plant life. Such fossils can be found in Cambrian rocks half a billion years old, then suddenly disappear in older pre-Cambrian rocks. But there is another kind of biosignature which only became apparent when instruments called gas chromatographs and mass spectrometers became available. When living organisms go through the chemical reactions needed to support life, they leave behind traces of their chemistry. There is a good reason why coal and oil are called fossil fuels. During the Carboniferous Period 300 million years ago, the climate was very warm, and immense masses of plant life thrived in the swampy, tropical jungles of the world. This plant life formed deep layers of peat-like deposits, which over time, were buried by layers of mineral sediments. Heat and pressure progressively altered the peat, finally producing the hard energy-rich substance we call coal. Fossil petroleum has a different, less welldefined history. The oil we pump out of the ground was originally produced from the remains of abundant marine microorganisms that fell to sea floors as sediment. Like all life, the phytoplankton cells stored energy in droplets called fat, and the droplets were deposited along with the cells as layers of sediment. Again under heat and pressure, the organic fat was “cracked” and hydrogenated, producing the long-chain hydrocarbons we call oil. To give some idea of the scale of oil deposits, every gallon of gasoline we use today required approximately 100 tons of phytoplankton to turn into fossil fuel.

The reason for explaining all this is to make the point that the most convincing evidence for a biological source of petroleum is that oil contains a set of hydrocarbons that can only have been synthesized by living organisms. These are called terpenes, hopanes, and steranes—the tough remnants of molecules that were once part of cell membranes.

As paleobiologists began to realize in the 1960s that it might be possible to find actual microscopic fossils of the earliest life, they began to search for remnants of Archaean Earth, which could preserve such biosignatures. By chance, certain rock formations in Western Australia, South Africa, Greenland, and Canada escaped the extensive tectonic processing that altered most other rocks at Earth's surface. Geologists had already found several such areas, giving them exotic names that are now famous, at least among origins of life researchers: Isua (Greenland), Gunflint (Canada), Fig Tree (South Africa), Spitzbergen (an island off the Norwegian coast) and Pilbara, Warawoona, and North Pole (in Western Australia). The oldest Canadian and Greenland rocks are 3.8 to 4 billion years old, but have undergone so much diagenesis (defined as geological processing by heat and pressure) that there is no hope of finding preserved fossils. However, Australian rocks that are 3.5 billion years old appear to have fossil stromatolites, layered mineral structures that today are known to be produced by bacteria growing in colonies called mats. These Australian rocks looked like a very promising place to search for the oldest microfossils, particularly because Stanley Awramik, Elso Barghoorn, and Andrew Knoll had already discovered clear evidence of microfossils in the 2.2-billionyear-old Gunflint chert of Canada.

Elso Barghoorn at Harvard pioneered studies of Precambrian microfossils. As early as 1966, Barghoorn and his student William Schopf had published a paper in Science that used organic biomarkers in an investigation of apparent microfossils they discovered in South African black cherts dated to be 3.1 billion years old. Barghoorn and Schopf also found pristane and phytane in the same chert, which supported the claim that the microscopic rodlike forms they observed were the remains of early bacteria, rather than inorganic structures. In more recent work, Roger Summons at MIT and Roger Buick at the University of Washington made extensive studies of the fossils and traces of organic compounds that they extracted from Western Australian rocks that are 2.7 billion years old. In a paper published in 2002, Summons and Buick reported that hopanes and steranes could be detected in those rocks, which suggested that photosynthetic microorganisms called cyanobacteria were producing oxygen more than two billion years ago. More surprising is the presence of sterane, a breakdown product of cholesterol that is present only in eukaryotic cells having nuclei. This would mean that eukaryotic organisms could have appeared much earlier than most scientists would have expected.

MICROFOSSILS FROM 3.5 BILLION YEARS AGO?

The early results from South Africa and Australia set the stage for a major controversy regarding the oldest evidence of life. In the mid-1960s, William (Bill) Schopf was a graduate student at Harvard, working with Elso Barghoorn. After completing his degree, Schopf joined the Geology faculty at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and began working on the central question of this chapter: What evidence can be discovered that will establish the antiquity of life on Earth? Stanley Awramik, a new faculty member at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), was also inspired by Barghoorn's approach and began to ask the same question. Awramik worked not only with Barghoorn, but also with Preston Cloud at UCSB, Andrew Knoll at Harvard, and Malcolm Walter in Australia. In 1983, Awramik was first author of a paper in Precambrian Research coauthored by Schopf and Walter, which reported possible microfossils in the cherts of Western Australia. Four years later, Bill Schopf and Bonnie Packer coauthored a paper in Science that finally caught everyone's attention, in part because Science has a much broader readership than Precambrian Reseach, but also because the results seemed clear enough to produce a consensus view that bacterial life was present on Earth at least 3.5 billion years ago.

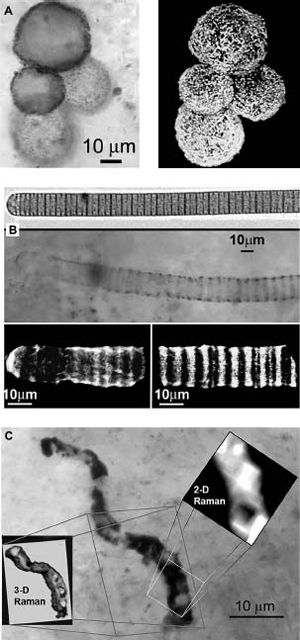

Several images of the apparent microfossils are shown in Figure 4. In a later paper Schopf published in 1993, some fairly bold claims were made, for instance, that 11 different kinds of bacteria could be discerned from the images, and that some of these were oxygen-producing photosynthetic cyanobacteria. Not only was Bill Schopf convinced that the fossils were real, but there was sufficient information to describe them as actual bacterial species of cyanobacteria. Making such a claim about a topic as important as the earliest life attracts immediate critical commentary, and Roger Buick published a cautionary note. It was largely ignored, and for nearly a decade, Schopfs interpretation was accepted, and the images were included in textbooks as representing actual fossils of the earliest known life.

FIGURE 4

Microfossils of ancient bacteria.

(A) (left panel) shows a micrograph of fossil microorganisms found in a rock formation 775 million years old from Kazakhstan. The right-hand panel shows a three-dimensional image of the same sample performed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM).

A living cyanobacterial species is shown in the top panel of (B), and the center panel is a light micrograph of an ancient cyanobacterium from the same rock formation as (A). The bottom panel of (B) is a CLSM image of the specimen. The contrast is produced by the organic material remaining in the fossil, which gives off a special kind of light called Raman emission that is characteristic of kerogen, a polymer produced when biological material undergoes aging.

(C) shows a filamentous structure found in 3.5-billionyear-old Australian rocks, four times older than those illustrated in (A) and (B). Is it an actual fossilized bacterium? Probably, because the Raman spectrum is characteristic of kerogen from biological material, and the 2-D Raman image shows interior compartments consistent with cellular life. Images courtesy of William Schopf.

Therefore, it was quite shocking for everyone in the field when a paper from Oxford University appeared in Nature in 2002 with Martin Brasier as lead author. In it, the authors challenged Schopfs interpretation of the Australian microfossils. Instead, the authors proposed a less dramatic interpretation—that the apparent fossils were simply artifacts produced when nonbiological carbon compounds form aggregates in hydrothermal vents.

Such a dramatic clash of opinion sometimes arises between personalities that are bold and risk-taking. Bill Schopf is nothing if not bold, and he was quite certain that the evidence was sufficient to make the assertion that these were actual microfossils of the earliest known life. Brasier and his coworkers were bold in their own fashion, and in their judgment, Schopf's evidence was insufficient. Furthermore, they were able to propose and support what is called a null hypothesis. A null hypothesis represents the most likely (and usually least interesting) possible explanation, in this case that the putative microfossils were not produced by life, but by geochemical processing of organic material like that in the Murchison meteorite. Until the null hypothesis is disproven, they argue, it is rash to jump to the conclusion that the dark microstructures are anything more than organic debris.

Nothing is as energizing as having your research results challenged in such a public forum. In order to respond, Bill Schopf has assembled a magnificent microscope facility that can produce three-dimensional images of the microfossils and furthermore provide what are called Raman spectra that tell whether the dark material is simply inorganic graphite or the polymeric kerogen expected to be produced by biological material. During a recent visit to Bill's lab, I sat at the microscope and watched a beautiful image of a microfossil appear on the screen and then rotate to produce a 3-D effect. This was a test run on a fossil from much younger rocks than the Australian Apex chert, but Bill has also applied the technique to the older samples. The resulting Raman results are consistent with the idea that the dark material of the microstructures is of biological origin. The Raman images match the shape of the black microfossil structures, and the spectral pattern is what one would expect of polymerized organic material, not the carbon of graphite (Figure 4C).

The bottom line is that we cannot yet be absolutely certain whether the enigmatic Apex chert structures are artifacts or evidence of the first life. Like jurors, other scientists are waiting for the two sides to present further evidence, which will require new approaches, new samples, and more work. As one of the jurors, what would convince me is more images of microfossils showing a pattern of structures. This is abundantly clear in more recent microfossils from about two billion years ago, but ancient fossils from 3.5 billion years ago are very rare, so this is likely to require an extensive (and very tedious) continuing exploration of ancient rocks. There must also be a convincing geological context. In other words, the fossils should be present in a rock formation that clearly matches the kind of rock that is likely to be a habitat for primitive bacterial colonies. Perhaps most important will be to demonstrate that similar structures cannot be produced by plausible nonbiological starting material.

LIFE 3.8 BILLION YEARS AGO? THE EVIDENCE FROM STABLE ISOTOPES

The case for life existing 3.5 billion years ago would be more convincing if evidence could show that life existed even earlier. Manfred Schidlowski, who worked at the Max Planck Institute in Mainz, Germany, had an idea. He knew that the Isua rocks of Greenland were 3.8 billion years old. Furthermore, even though they had undergone considerable geological processing, the rocks contained detectable traces of organic carbon. Could this carbon be a biomarker for life? The same stable isotope analysis described earlier for analyzing the oxygen content of zircons might provide an answer. The technique takes advantage of the fact that there are two isotopes of carbon, the most common (~99%) being carbon with an atomic weight of 12, mixed with the much less common carbon 13 (~1%). Schidlowski also knew that when living organisms such as photosynthetic bacteria take up carbon dioxide to use as a carbon source for growth, there is a slight tendency to capture the lighter isotope in preference to the heavier isotope. This difference can be compared against a nonbiological carbon compound such as calcium carbonate in limestone. Thousands of such measurements have consistently shown that the organic material produced by living organisms is “lighter” in the sense that it contains more carbon 12 than expected from comparison with the carbon in limestone. For convenience, the difference is expressed in parts per 1,000 (rather than parts per 100, which would be the more familiar percent in common use), and typical results for biomass range from –20 to –50. When Schidlowki measured the same value for Isua carbon it was –27, in the range expected for carbon that had been processed by living organisms. (The minus sign indicates a range lighter than carbonate mineral.)

Could life really be that old? Despite the intrinsic interest of Schidlowski's result, it received little attention because there was still uncertainty about the actual age of the Isua rocks and their geological history. But then in the mid-1990s, Stephen Mojzsis, a graduate student at UCLA, decided to try a new technique on Isua rocks. Mojzsis had access to the kind of ion microprobe instrument that John Valley had used on zircons. Mojzsis reasoned that if the organics really were a product of life, they might be associated with a calcium phosphate mineral called apatite that was scattered throughout the mineral matrix of Isua rocks. Apatite is the mineral of bones and teeth today, and phosphate is used by all living organisms. Perhaps during diagenesis it would be turned into calcium phosphate while the organic carbon content of the microorganism would become graphite particles embedded in the apatite matrix. The apatite mineral would then protect the graphite from diagenesis. (Graphite is a form of carbon produced when organic carbon is subjected to heat and pressure sufficient to drive off all of the other atoms present, particularly hydrogen and oxygen.)

Mojzsis used the microprobe to scan microscopic apatite deposits in rocks from Isua as well as rocks called banded iron formations that were sampled from Akilia, an offshore island in Greenland. By this tim e, the rocks had been dated much more accurately by other workers to be 3.37 billion years for Isua and 3.85 billion years for the Akilia rocks. The results were astonishing: –30 for Isua and –37 for Akilia! This was almost too good to be true because these numbers are well within the range expected if the carbon atoms had been processed by some form of metabolism.

Alas, these results are now also in dispute, not because the measurements are incorrect, but instead due to interpretation of the rocks themselves. Mojzsis assumed, as others had done, that the Isua rocks were primarily sedimentary material produced in an aqueous environment that had later been subjected to high pressure and temperature. In their 2002 paper, Mark van Zuilen and coworkers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography showed that the rock was not sedimentary, but instead was produced when hot water reacted with older crustal minerals. Carbon in the form of graphite can be produced when carbonate undergoes high temperature processing, rather than from a biological source. Van Zullen's group concluded that the light carbon in the graphite must have been produced by geochemical reactions: “The new observations thus call for a reassessment of previously presented evidence for ancient traces of life in the highly metamorphosed Early Archaean rock record.”

WHAT WAS IT LIKE FOUR BILLION YEARS AGO?

We can now put together all the information from Chapters 2 and 3 by describing what Earth would have looked like if we could somehow travel back in time four billion years to the early Archaean Eon, before life began. We might find ourselves standing on the rocky shore of a volcanic island. It is very hot, around 70°C, and the atmosphere is a toxic mixture of carbon dioxide, nitrogen and volcanic gases. For this reason we must wear protective clothing, an air-conditioned space suit with an oxygen supply. In the distance we can see other land masses rising from the sea, some of which are active volcanoes. The rocks beneath our feet are composed of dark lava with volcanic ash filling the crevices. Hot springs boil all around us. The fairly salty sea water has an odd greenish tint from all the dissolved iron that it contains. White deposits of dried salt on the lava rocks show where small tide pools have evaporated. Rain falling in the nearby volcanic peaks causes freshwater ponds to form a few meters above the beach. These are constantly being filled by small rivulets of water cascading down the mountainside, then drying out in the heat. Suddenly the landscape is brilliantly illuminated for several seconds as a blinding white streak silently crosses the sky and descends into the sea just over the horizon, where an even brighter flash of light appears. A minute later we hear a thunderous roar, followed by a pulsing shockwave that nearly knocks us over. A small asteroid, maybe 100 meters in diameter, has penetrated the atmosphere at 20 kilometers per second and has crashed into the ocean several miles away—one of many such impacts that occur every day. A thin dark line on the ocean horizon advances toward us. The tsunami from the meteorite impact is heading our way, so we fast forward four billion years to a more familiar setting.

Back home, we have only one thought from our experience in the prebiotic Archaean Eon: How could life begin in such an unpromising environment? And this brings us to a fundamental question that is still unanswered: Is the origin of life a common event? In that case, there might have been multiple origins of life, but each attempt was snuffed out by the giant impact events associated with the Late Heavy Bombardment. The life we see today are the survivors that managed to live through the last giant impact or that started up as soon as it was safe to do so.

The alternative is that the origin of life is exceedingly rare, requiring half a billion years or more to happen just once on a habitable planet like early Earth that has just the right set of conditions. We just don't know the answer yet, and this book is a progress report on our attempts to find out. If I had to guess, I would be optimistic. I think that we are just at the point of being able to produce a form of synthetic life in the laboratory. When we can do that, we will have a much better understanding of how life can begin, and how likely it is that a similar process could occur on early Earth

CONNECTIONS

The stable isotope composition of oxygen in zircons supports the presence of oceans and land masses at least 4.4 billion years ago. The initial reactions leading to the production of complex organic compounds in bodies of water could have begun at that time. Evidence from stable isotopes of carbon suggests that organic carbon was being processed by living organisms about 3.8 billion years ago, but the evidence for this is under debate and not yet resolved. The first possible microfossils of bacterial life are present in Australian rocks that are 3.5 billion years old, but these are also disputed. The earliest undisputed microfossils are in rocks that are 2.5 billion years old. Bacterial life was abundant more than two billion years ago, and molecular fossils called steranes suggest that eukaryotic life appeared about this same time. Simple forms of multicellular life were present over one billion years ago, and hard-shelled organisms became abundant in the fossil record during the Cambrian Period 540 million years ago.

The next chapter will describe the kinds of organic compounds that were likely to be present in the environment at the time of life's origin, and then we will see how such compounds can interact with each other to produce ever more complex structures on the evolutionary pathway toward the first forms of life. We will see how experiments in the laboratory attempt to simulate conditions on early Earth, but an important point is that none of these simulations comes close to the actual conditions described in Chapters 2 and 3. The reason for this is a good one, having to do with standard scientific practice to keep experimental conditions as simple as possible in order to prevent confusion. Such simplicity, although essential in designing experiments, may also be limiting progress in origins of life research. I will argue that there is another principle I call sufficient complexity that is essential if we are to reproduce the origin of life in the laboratory.