15

PROSPECTS FOR SYNTHETIC LIFE

Invention, it must be humbly admitted, does not consist of creating out of void, but out of chaos.

MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT SHELLEY, 1818

In Mary Shelley's classic tale, Dr. Victor Frankenstein assembled a human body from parts retrieved from corpses. The novel, first published nearly 200 years ago, raised questions that we would now consider to fall within the realm of bioethics. If Dr. Frankenstein wanted to carry out his experiment today, he would need to bring it to the attention of the IRB (Institutional Review Board) at his university who would doubtless reject it. And yet, a number of laboratories around the world are attempting to perform a reconstitution of life eerily similar to Frankenstein's dream—to invent something alive, but on a microscopic scale. There is even a name for such science: synthetic biology.

Here I will briefly trace the history of attempts to fabricate artificial cells that increasingly are approaching the definition of living organisms. These efforts have not yet succeeded, but there is reason to believe that the goal may be achieved in the next decade. The point is that as we attempt to assemble synthetic life, we are retracing some of the steps that led to the origin of life, and we can learn from successes and failures.

Assembling a system of molecules capable of reproduction was first achieved in 1955, when it was discovered by Heinz Fraenkel-Conrat and Robley Williams at the University of California Berkeley that the tobacco mosaic virus could be separated into its coat protein and RNA. Neither component was active by itself, but when mixed together, the two parts reassembled into the infectious agent. Although viruses are not considered to be alive in the usual sense of the word, a successful reconstitution of viral functions encouraged other investigators to attempt the reassembly of more complex systems. In the 1970s, Efraim Racker at Cornell University was the most successful practitioner of this art, using detergents such as deoxycholic acid to disperse membranous components of cells. When the detergent was removed, small membranous vesicles formed that contained the original components, albeit somewhat scrambled in their orientation. Despite the scrambling, Racker and his colleagues were able to reconstitute electron transport reactions and ATP synthesis of mitochondrial and chloroplast membranes.

Similar techniques were soon applied to other biological structures and functions. For instance, Walther Stoekenius and Dieter Oesterheldt at the University of California San Francisco reconstituted the proton pump of purple membranes isolated from a halophilic bacterial species that uses the energy of a proton gradient to synthesize ATP. In a remarkable collaboration, Racker and Stoeckenius teamed up to produce a membranous system containing both the proton pump of halobacteria and the ATP synthase of mitochondria, and they demonstrated that the hybrid membranous structures could synthesize ATP using light as an energy source. The paper that Racker and Stoeckenius wrote has often been cited as the publication that finally confirmed chemiosmotic synthesis of ATP, leading to a Nobel Prize for Peter Mitchell in 1978.

The point of this brief history is that relatively complex biological functions can be reconstituted by self-assembly of their dispersed components. Why not try to reconstitute a whole cell? If this turns out to be possible, perhaps it will help us untangle what we mean by “life” and even elucidate the major steps that led to the origin of cellular life nearly four billion years ago. Let's first consider what might happen if we disassembled a microscopic living organism and tried to put the pieces back together. We would not try this with something like amoebas because nucleated cells are too complicated. Instead, we should use a much simpler form of life, such as a tiny bacterium called Mycoplasma, a kind of microbial parasite that can only live in a relatively rich nutrient environment. Only 450 genes are present in its genome, while more complex bacteria such as E. coli have 10 times that number. The human genome, by way of contrast, is estimated to have 20,000 to 30,000 genes at last count, with the actual function known for less than half of these. The cells of Mycoplasma are bounded by a naked membrane composed of a mixture of lipids in the form of a bimolecular layer common to all membranes, with a variety of functional proteins and enzymes integrated into the bilayer. Some of the enzymes are responsible for extracting energy from nutrients and using the energy to synthesize ATP, while others are essential transporters of nutrients from the external medium into the cell. Examples of nutrients are an energy source such as glucose, amino acids as building blocks for proteins, and phosphate for nucleic acids. The interior contents of the cell include a circular strand of DNA having genes responsible for synthesizing proteins required for metabolism. A variety of structural components is also present, including thousands of ribosomes, the molecular machines that synthesize proteins, and hundreds of soluble enzymes involved in metabolism.

What happens if we add a detergent to Mycoplasma? The detergent immediately penetrates the lipid bilayer, which becomes unstable and breaks up into smaller particles containing lipids, membrane proteins, and the detergent molecules. With the membrane gone, the interior components are released. What we see visually is that the slightly turbid suspension of bacteria becomes clear, and if examined with a microscope, no cells are visible. The resulting solution contains all the components of the original living cell, but they have become diluted and disorganized.

Now we can try to reassemble the components by injecting a certain amount of order back into the system. This is done by a process called dialysis, in which smaller molecules like detergents leak through a porous membrane while larger molecules remain behind. (The same process is used to treat patients with kidney disease.) As the detergent leaves, the lipids self-assemble into bilayers that take the form of small vesicles. The membranous boundaries of the vesicles incorporate most of the functional enzymes and transport proteins that were present in the bacterial cell membranes, and each vesicle contains a random sample of the original contents of the bacterial cell, with one exception: The circle of DNA, the genome, that was originally packed tightly into the original living cells, has unraveled and is too large to be captured when the vesicles reassemble.

To be truly alive, the vesicles need most if not all of their original genes in the form of a DNA strand containing the genetic information required for 1,000 or so different proteins and RNA species, over half of which are the components of the ribosomes themselves. They would need genes for polymerase enzymes so that the DNA could be replicated as part of the growth process and a way for lipids to be synthesized because the membranous boundary must grow to accommodate the internal growth. Transport proteins must be synthesized and incorporated into the lipid bilayer, otherwise the vesicles have no access to external sources of nutrients and energy. A whole set of regulatory processes must be in place so that all of this growth is coordinated. Finally, when the vesicles grow to approximately twice their original size, there must be a way for them to divide into daughter cells that share the original genetic information.

THE SMALLEST CELLS

Well, how close are we to achieving true synthetic life in the laboratory? One way to get at this question is first to ask how small a living organism can be because in general, smaller means simpler, and it is best to first try making simple forms of life. In 1996, the images of the putative fossil bacteria in the Mars meteorite that I described in the Introduction were claimed to be in the range of 100 nanometers or less. This immediately raised suspicions among biologists, who knew that typical bacteria were approximately 10 times that diameter, which corresponds to a thousand-fold greater volume. Furthermore, ribosomes are 20 nanometers in diameter, which means that only a few could fit into such tiny cells.

This question spurred the National Academy of Science to convene a study committee with the specific charge of estimating the smallest version of life that is theoretically possible. The committee came up with an estimate of 250 genes in the DNA, and a few dozen ribosomes, all in a membranous compartment 200 nanometers in diameter. This is comfortably close to the smallest known form of life, Mycoplasma, with 450 genes.

Of course, this is life as we know it, which is based on a highly evolved relationship between DNA, RNA, ribosomes, and protein catalysts. It seems impossible that the first forms of life sprang into existence with such a complex system of interacting molecules, so perhaps smaller versions of exotic life are, in fact, possible. There are even controversial claims that something called nanobacteria exist everywhere and may cause certain diseases by producing deposits of a calcium phosphate mineral called apatite.

Evidence from phylogenetic analysis suggests that microorganisms resembling today's bacteria were the first form of cellular life. As described in Chapter 3, hints of their existence can be found in the fossil record of Australian rocks at least 3.5 billion years old. Over the intervening years between life's beginnings and now, evolution has produced bacteria which are more advanced than the first cellular life. The machinery of life has become so advanced that when researchers began subtracting genes in one of the simplest known bacterial species, they reached a limit of approximately 265 to 350 genes that appears to be the absolute minimum requirement for contemporary bacterial cells. Yet life did not spring into existence with a full complement of 300+ genes, ribosomes, membrane transport systems, metabolism and the DNA→RNA→protein information transfer that dominates all life today. There must have been something simpler, a kind of scaffold life that was left behind in the evolutionary rubble.

Can we reproduce that scaffold? One possible approach was suggested by the “RNA World” concept that arose from the discovery of ribozymes, which are RNA structures that had catalytic activities. The idea was greatly strengthened when it was discovered that the catalytic core of ribosomes is not composed of protein at the active site, but instead is only a tiny bit of RNA machinery. This is convincing evidence that RNA likely came first and then was overlaid by more complex and efficient protein machinery.

Another approach to the origin of life is now underway. Instead of subtracting genes from an existing organism, researchers are attempting to incorporate one or a few genes into tiny artificial vesicles to produce molecular systems that display all the properties of life. The properties of the system may then provide clues to the process by which life began in a natural setting of early Earth.

What would such a system do? We can answer this question by listing the steps that would be required for a living system to be reconstituted in the laboratory or to emerge as the first cellular life on early Earth:

- Boundary membranes are formed by self-assembly of lipid molecules.

- Macromolecules are encapsulated, yet smaller nutrient molecules can cross the membrane barrier.

- The macromolecules grow by polymerizing the nutrient molecules.

- The energy required to drive polymerization is contained in the nutrients themselves or supplied to the system by a metabolic process.

- The energy is coupled to the synthesis of activated monomers which, in turn, are used to make polymers.

- Some of the polymers are selected as macromolecular catalysts that can speed the growth process, and the macromolecular catalysts themselves are reproduced during growth.

- Information is captured in the sequence of monomers in one set of polymers.

- The information is used to direct the growth of catalytic polymers.

- The membrane-bounded system of macromolecules can divide into smaller structures.

- Genetic information is passed between generations by duplicating the sequences and sharing them between daughter cells.

- Occasional mistakes (mutations) are made during replication or transmission of information so that evolution can occur by selection of variations within the population of cells.

Looking down this list, one is struck by the complexity of even the simplest form of life. This is why it has been so difficult to “define” life in the usual sense of a definition— that is, boiled down to a few sentences in a dictionary. Life is a complex system that cannot be captured in a few sentences, so perhaps a list of its observed properties is the best we can ever hope to do.

It is also striking that most of the individual steps have been reproduced in the laboratory. The task now is to integrate the functions into lipid vesicles to see how far we can get in reconstituting a living cell.

The process begins by encapsulating samples of cytoplasmic components from living cells like E. coli .As described in Chapter 7, encapsulation of large molecules is the simplest step toward the origin of cellular life. Pier Luigi Luisi and his coworkers at the Eigennössische Technische Hochschule in Zurich, Switzerland (usually and understandably referred to as ETH), made the first attempt to assemble a translation system by encapsulating ribosomes in lipid vesicles along with an RNA that codes for a specific amino acid, phenylalanine. The amino acid was attached to transfer RNA so that it could be used by the ribosomes. However, because the lipid bilayer was impermeable, ribosomal translation was limited to the small number of amino acids that were encapsulated within the vesicles. This is the kind of hurdle that is discovered when we attempt to assemble functioning cells. It forces us to consider mechanisms by which the first forms of cellular life could transport nutrients inward across their boundary membrane.

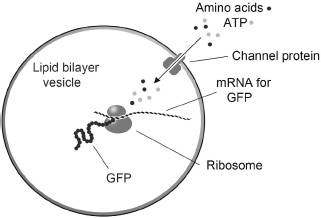

In 2004, Vincent Noireaux and Albert Libchaber, at Rockefeller University, published an elegant solution to the permeability problem. They broke open bacteria, again using E. coli, and captured samples of the bacterial cytoplasm in lipid vesicles. The aim of the experiment was to produce a functioning protein, so the complex mixture consisted of ribosomes, transfer RNAs, and the 100 or so other components required for protein synthesis. The researchers then carefully chose two genes to translate, one for green fluorescent protein (GFP), a marker for protein synthesis, and a second gene for a pore-forming protein called alpha hemolysin. If the system worked as planned, the GFP would accumulate in the vesicles as a visual marker for protein synthesis, and the hemolysin would allow externally added “nutrients” in the form of amino acids and ATP, the universal energy source required for protein synthesis, to cross the membrane barrier and supply the translation process with energy and monomers (Figure 31).

FIGURE 31

In 2004, Vincent Noireaux and Albert Libchaber published a method by which ribosomes could be encapsulated in lipid vesicles. They showed that the ribosomes could synthesize green fluorescent protein (GFP) using messenger RNA that codes for the GFP amino acid sequence. Because lipid membranes are impermeable to substrates, the vesicles also included mRNA for alpha hemolysin, which was synthesized by the ribosomes and formed channels in the membrane. The channels allowed externally added “nutrients” such as amino acids and ATP to enter the vesicles and supply the encapsulated ribosomes with necessary ingredients.

The system worked as expected. The vesicles began to glow with the classic green fluorescence of GFP, and the hemolysin allowed synthesis to continue for as long as four days. Tetsuya Yomo and his research group at Osaka University have gone a step further with a similar encapsulated translation system in which the GFP gene is present in a strand of DNA. They refer to their system as a genetic cascade because the GFP gene is transcribed into messenger RNA, which then directs synthesis of the protein.

CONNECTIONS

Can we now synthesize life? This question brings us to the limits of what we can do with our current techniques, and the answer is: not yet. Everything in the system grows and reproduces except the catalytic macromolecules themselves. All of the systems to date depend on polymerase enzymes or ribosomes, and even though every other part of the system can grow and reproduce, the catalysts get left behind.

The final challenge is to encapsulate a system of macromolecules that can make more of themselves by catalysis and template-directed synthesis. A little progress has been made to this end. David Bartel and his coworkers at the Whitehead Institute, using a technique developed for selection and molecular evolution, produced a ribozyme that can grow by polymerization, in which the ribozyme copies a sequence of bases in its own structure. So far, the polymerization has only copied a string of 14 nucleotides, but this was a good start, and Peter Unrau at Simon Fraser University recently reported a similar system that could copy sequences up to 20 nucleotides. If a ribozyme system can be found that catalyzes its own complete synthesis using genetic information encoded in its structure, it could rightly be claimed to have the essential property that is lacking so far in artificial cell models: reproduction of the catalyst itself. Given such a ribozyme, it is not difficult to imagine its incorporation into a system of lipid vesicles that would have the basic properties of the living state.