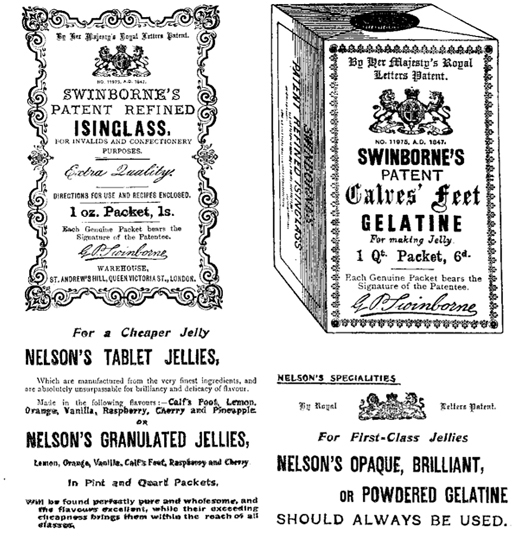

Figure 1. Advertisements such as these promoted the use of improved ‘patent’ gelatines in the mid-nineteenth century.

The substance which is the basis of the jellies into which certain animal tissues (skin, tendons, ligaments, the matrix of bones, etc.) are converted when treated by hot water for some time. It is amorphous, brittle, without taste or smell, transparent, and of a faint yellow tint; and is composed of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulphur.

This definition provided by the Oxford English Dictionary covers all the essential characteristics of this remarkable substance.1 It is based on collagen, a stiff fibrous protein found in all animal skin and connective tissue. Instead of being a single molecule it has three separate molecules twisted around each other like strands in a rope to form a triple helix structure, tough and almost inedible. Only by heating the collagen above some 70°C does the helix unwind, its separate strand-like molecules interacting with each other to form a random three-dimensional network. This holds the surrounding water in place, making it behave more like a solid than a liquid, in other words, a jelly. This process is closely governed by temperature, the molecules separating every time they exceed about 30°C, and re-connecting when they fall beneath about 15°C, phenomena we know as melting and setting.2 If raw egg-whites, for instance, are mixed into the melted jelly and then heated, they form per-manent molecular links with the gelatin strands and so form a jelly which cannot be re-melted. Similarly the addition of certain enzymes, such as those in fresh pineapple or kiwi fruit, can break down the links in the gelatin structure, causing it to become unsettable.

Medieval cooks were certainly ignorant of the scientific explanation behind the formation of jelly, but this did not prevent them from developing considerable skill in its prepa-ration. When any of their meats and fishes with a high collagen content had been boiled to tenderness and then allowed to cool, they could not fail to have noticed how they set to firmness, the fats rising to the surface and the sediment dropping to the bottom. Once tasted, they would appreciate the pleasure of feeling it melt on their tongues, the flavours it released and the satisfying glutinous smoothness it left in the mouth. From this stage it would take little ingenuity to start to make jelly not as a by-product, but as a dish in its own right.

Probably the earliest English recipe for ‘jelly’ comes from a manuscript written in the first quarter of the fourteenth century:3

Gelee. Vihs isodeen in win & water & saffron & paudre of gynger & kanele, galingal, & beo idon in a vessel ywryen clanlicke; ye colour quyte.

Experience shows that this method of just cooking fish in white wine, saffron, ginger, cinnamon and galingal only produces a spicy fish stew, nothing remotely resembling anything we could ever describe as a jelly. A further recipe of about 1381 is similarly unpromising:4

For to make mete gelee that it be wel chariaunt, tak wyte wyn & a perty of water & saffroun & gode spicis & flesh of piggys or of hennys, or fresch fisch, & boyle tham togedere; & after, wan yt ys boylyd & cold, dres yt in dischis & serve forthe.

This thick pork or chicken stew might just hold itself together in a serving dish, if the weather was cold, but again lacks sufficient gelatin to produce a good jelly. However, the same manuscript also contains the following:5

For to make a gely, tak hoggys fet other pyggys, other erys, other pertrichys, othere chiconys, & do hem togedere & seth hem in a pot; & do in hem flowre of canel and clowys hole or grounde. Do thereto vinegere, & tak & do the broth in a clere vessel of all thys, & tak the flesch & kerf yt in smale morselys & do yt therein. Tak powder of gelyngale & cast above & lat yt kele. Tak bronchys of ye lorere tre & styk over it, & kep yt al so longe as thou wilt & serve yt forth.

This is an excellent recipe, one which any traditional farmer’s wife or pork butcher would immediately recognize as a stiff, jellied brawn. The feet and ears or porkers and suckling pigs were among the best sources of gelatin, giving a rich, glutinous stock. Proof of how successful this recipe would be is provided by the following version published almost six hundred years later in The Farmer’s Weekly. It was sent in by Mrs H.M. Diamond of Worcestershire.6

2 pig’s feet, 1lb of shoulder steak, ham scraps … pepper, salt. Stew the … pig’s feet very slowly with the shoulder steak and ham scraps. Season with pepper and salt. When thoroughly cooked cut up the meat into small pieces, and pour with the liquor into a mould which has been well rinsed in cold water, then leave to set and turn out next day... This dish is economical and easily prepared – which is what we require in these days when, as farmers’ wives, it is necessary to consider expenses and our time.

The first evidence of care being taken to ensure that jelly stock was being filtered and reduced separately to ensure good clarity and firmness comes from recipes such as the following of around 1390. After being well boiled with the meat or fish, the stock was to be passed:7

thurgh a cloth in to an erthen panne … Lat it seeth {boil or simmer}& skym it wel. Whan it is ysode {boiled}, dof the grees clene: cowche {the flesh or fish}on chargours & cole the sewe thorow a cloth onoward & serve it forth colde.

The jellies served at the earl of Derby’s table were certainly being clarified by careful filtration at this time, his accounts for 1393 recording money spent:8 ‘ex prop iii vergis tele pro 1 gelecloth xviiid.’

The late fourteenth century saw the first documented use of calf ’s feet as a source of gelatin, this appearing in a recipe in the Forme of Curye ‘compiled of the chef Maister Cokes of kyng Richard the Se{cu}nde … the best and ryallest vyaund{er}of alle cristen {K}ynges.’9 By the fifteenth century calf ’s feet were being used to create a clear firm-setting jelly stock which was then used as a separate culinary medium in its own right. In some recipes small chickens and the sides of sucking pigs were poached in it, the stock then being re-warmed, flavoured, coloured, skimmed, strained and eventually poured over the jointed meat in a dish, and left to set. To check if the stock would form a jelly, the cook was advised to ‘put thin{e} hande ther-on; & if thin{e}hand waxe clammy; it is a syne of godenesse.’10 In others, the jelly stock was mixed with almond milk, sugar and colourings to create what was then called Vyaunde leche, a ‘sliceable food’,11 and, in later centuries, blancmange.

Obviously calfs-foot jelly could not be consumed on fish days, when the Church banned the eating of meat. These included every Friday, (the day of the crucifixion), Saturday (dedicated to the Virgin Mary) and Wednesday (when Judas accepted the thirty pieces of silver). If jellies were to be served on these days, they would have to be based on a strong fish stock. Instead of calf’s feet, barbell, conger eel, plaice or thornback were boiled in fish stock until they would jellify. To test this, the cook was to ‘take up som thereof, & pour hit on the breed of a disch, & let hit be cold; & ther thu shall se where it be chargeaunt; or els take more fisch that woll gely, & put hit theryn.’12 If it still would not set, another contemporary recipe advised further simmering with ‘Soundys of watteryd Stokkefysshe, or ellys Skynnys, or Plays.’ The ‘sounds’ were swim-bladders, at this time those of the cod, which were already being used to mix fine paints and make glue for book-binding in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. They were ideal for making jellies too.13

By the end of the medieval period the techniques for making clear gelatinous stocks were thoroughly understood and practised in all major kitchens. The use of ‘jelly’ as a word to describe those versions containing pieces of cooked meat or fish was now rapidly falling out of common parlance. From now on it was to be restricted to the clarified, sweetened and flavoured varieties which we still recognize as jellies today. Most jellies remained relatively flaccid, however, lying dormant either in or on their dishes, even those cut in slices barely standing up by themselves, and being totally unable to maintain the shape given by a mould.

In the early 1500s a more effective gelling ingredient began to be imported from Europe. This was isinglass, the swim-bladder or ‘sound’ of the sturgeon, composed almost entirely of gelatin. It was subject to a high level of customs duty, at £1 13s. 4d. per 100 lb or 4d. the pound in 1545.14 Most appears to have been employed in making glues and sizes, but it had certainly entered culinary use by the 1590s when Thomas Dawson instructed cooks to:15

Take a quart of newe milke, and three ounces weight of Isinglasse, halfe a pounde of beaten suger, and stirre them together, and let it boile half a quarter of an hower till it be thicke, stirring them al the while.

The interest in this recipe is twofold; firstly it assumes that the reader is already familiar with isinglass, suggesting that it had been used for jellymaking for some time, and secondly, it boils insinglass in milk for half an hour. In this, it exploits the great distinction between isinglass and other forms of gelatin; it can be boiled with milk without splitting it into curds and whey. This problem always occurs if a milk and gelatin solution is heated above around 70°C.

Both gelatin and isinglass continued to be the principal ingredients used for making jellies throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The only piece of specialized equipment required for their preparation was the jelly-bag, an open-topped cone of cloth used for finely filtering the stock. They had already been made of woollen cloth, probably flannel, for centuries, the Durham Priory account roll for 1516-17 recording:16 ‘Pro una uln. Panni lanei pro le gelypoke 8d.’

Unless kept hot, the jelly set within them instead of dripping through. Patrick Lamb, Master Cook to Charles II, James II, William and Mary and Queen Anne, prepared his jelly bags by washing them in cold water, drying them away from any smoke, filling them with the stock, and then hanging them on a spit, apparently close to the fire, to keep their contents liquid.17

By the mid-eighteenth century, ladies who wished to display fine jellies on their dining tables were being offered a completely trouble-free way of acquiring them: they could buy them ready-made from a professional confectioner. In Manchester, for example, they could call at Mrs Elizabeth Raffald’s at 12 Market Place for all their ‘Creams, Jellies, Flummery … which any lady may examine at pleasure … daily, in my own shop’.18 Her sister Mary Whitaker similarly offered ‘Jellies, Creams, Flummery, Fish Ponds, Transparent Puddings’ from her shop opposite the King’s Head in Salford.19 In fashionable Bath, the newspapers carried advertisements for:20

JOSEPH BICK, PASTRY COOK and Confectioner Remov’d from Broad-Street … Jellies fresh every day 3s. per Doz. Blancmange and Jelly ornamented for Dishes, Compote, Creams …

Making a reliably clear, firm and successful jelly from basic ingredients remained a challenge for most everyday cooks and housewives. What they needed was a source of pre-prepared gelatin, one they could keep in their store cupboards and use at their convenience.

The isinglass or ‘Muscovy Talc’ imported from Russia most closely met these requirements. In Russia the ‘nervous and mucilaginous parts of {sturgeon}were boiled to the consistency of a jelly, they spread it on a leaf of paper, and form it into cakes, in which state it is sent to us.’21 This would form the basis of the ‘Adams’ prepared Isinglass’ being made by John Adams of Cushion Court, Old Broad Street, London, in 1824.22 In 1847 G.P. Swinborne took out patent no. 11975 for the purification of both isinglass and gelatin by ‘the solvent power of water alone.’

In the patent, George Philbrick Swinborne, of Pimlico, stated that to date it had been the general practice to break down hides or skins with acids, alkalis and mechanical means, reducing them to pulp in a paper-grinding machine, and then clarify them with blood. In contrast, his new method took fresh hides or skins, free from hair, cut them into fine shavings, soaked them in water for five or six hours, then renewed the water two or three times each day until no smell remained. Having been drained, they were put into a vessel with hot, not boiling water, to extract the gelatin, which was then either run off as a clear solution, or strained through a linen cloth on to beds of slate to set. Next it was hung up in nets to dry and finally cut up for packaging.

For his isinglass, cod sounds or other gelatinous parts of fish were treated in the same manner.

To confirm the quality of their products, Swinborne’s published a report commissioned from Professor W.T. Brande, F.R.S. and J.T. Cooper, the leading analytical chemists of the day. They stated that the ‘Patent Refined Isinglass’ was ‘perfectly clear from colour, taste and smell; makes a clear solution in hot water, leaves no deposit {and}is stronger, firmer, and more durable than that prepared from the same proportions of Russian Isinglass.’ As for the gelatin: ‘though it is not so free from colour nor so powerful a gelatiniser, yet it can be produced at a much lower price, may become very generally useful, especially as if kept dry it will undergo no change in any climate … there are many other Gelatines in the market, which we deem objectionable.’23

By reprinting this report as part of a strong advertising campaign which continued over the following half century or more, Swinborne’s isinglass and gelatin became one of the leading brands supplied to the wholesale and retail trade. Their products came in elegantly printed and sealed packets, those for isinglass containing one ounce, and the gelatin, enough to set a quart of liquid. The housewives and cooks who bought them were virtually guaranteed good, trouble-free and attractive jellies, especially if they followed the recipes published on the packets and in booklets such as The Pastry Cook & Confectioner which went through fifteen editions between 1879 and 1911.

In mid-Victorian England there was an increasing unease about all manufactured products, for adulteration was rife. In 1855 one analyst decided to buy samples of isinglass from twenty-seven of the leading London grocers and Italian warehousemen, to see if they were genuine. Those of Fortnum & Mason of Picadilly passed the test, selling it for 1s 2d the ounce, so did:

VICKERS

GENUINE RUSSIAN ISINGLASS

FOR INVALIDS AND CULINARY USE

This article is guaranteed to be prepared from the pure Russian isinglass, as imported, and has not undergone any other process besides being passed through rollers and cut into shreds, for the purpose of making it soluble. Purchasers who are desirous of protecting themselves from the adulteration which is now extensively practised are recommended to ask for “VICKERS’ GENUINE RUSSIAN ISINGLASS” in sealed packets (containing one ounce, two ounces, a quarter of a pound, or one pound), that being the surest guarantee for their always obtaining a really PURE AND UNADULTERATED ARTICLE.

FACTORY, 23 LITTLE BRITAIN, LONDON.

The results of the analysis confirmed the need for caution. More than a third of the suppliers fobbed off customers seeking isinglass with cheap gelatin which ought to have cost around 6d. the ounce, instead charging up to 1s. 4d. the ounce thus more than doubling their profits. Clearly it was worthwhile to buy a branded isinglass with an impeccable reputation, such as Swinborne’s. However, when the chemist bought a sealed packet of ‘SWINBORNE’S PATENT REFINED ISINGLASS’ from Sidney, Manduell, & Wells of 8 Ludgate Hill, he found it contained nothing but ordinary gelatin. Swinborne’s, however, carried on publishing the 1847 guarantee of purity,and promoting their gelatin ‘isinglass’. Effective legislation to counteract such substitution was some years away from enactment.

In her Book of Household Management of 1861, Mrs Beeton continued to give directions for making calf’s foot and cow-heel jellies, the latter requiring an eight-hour boil and at least forty-five minutes to clarify. Her recipe for isinglass or gelatin jellies still required their stocks to be boiled, have the scum removed and then be filtered through a jelly-bag, since most still varied so much in quality and strength:24

The best isinglass is brought from Russia, some of an inferior kind is brought from North and South America and the East Indies; the several varieties may be had from the wholesale dealers in isinglass in London. In choosing isinglass for domestic use, select that which is whitest, has no unpleasant odour, and which dissolves most readily in water … If the isinglass is adulterated with gelatin … in boiling water the gelatine will not so completely dissolve as the isinglass; in cold water it becomes clear and jelly-like, and in vinegar it will harden.

Such problems could be avoided by buying either a pure, reliable brand, or a sealed bottle of ready-made and flavoured jelly. The latter had only to be uncorked, stood in a pan of hot water until completely dissolved, and poured into a freshly-rinsed mould.

From this period many companies made gelatins for domestic use, some of them being closely linked to the leather industry, the by-products of which provided the necessary raw ingredients. In Leeds, the centre of the British leather trade, William Oldroyd & Sons made the ‘Finest Powdered Calf Gelatine, Quality Unequalled’ at their massive Scott Hall Mills which they depicted in the frontispiece of their promotional recipe booklet.25 Such products were now in widespread use, even though:26

It {was}within the memory of many persons that jelly was at one time only to be made from Calf ’s Feet by a slow, difficult, and expensive process. There is indeed a story told of the wife of a lawyer early in the {nineteenth}century having appropriated some valuable parchment deeds to make jelly when she could not procure Calf ’s Feet. But the secret that it could be so made was carefully guarded by the possessors of it.

The first company to promote the use of skin-based gelatins on a large scale was G. Nelson, Dale & Co. of Emscote Mills in Warwick. From 1881 it published a 124-page red cloth-covered hardback recipe book entitled Nelson’s Home Comforts containing recipes for its products, as well as pages of advertisements for its:

Invaluable to Invalids, Made in the following flavours; Calf’s Foot, Lemon, Sherry, Port, Orange and Cherry.

Patent Opaque Gelatine … sold in packets from 6d to 7/6d’

Powdered Gelatine … dissolves readily in boiling water … 1 lb. tins 3/3, ½ lb. 1/9, ¼ lb. 1 / -

Leaf Gelatine, IN VARIOUS QUALITIES. For all who have been in the habit of using Foreign Leaf Gelatines this will be found in all respects superior and of more uniform quality and strength. In 1 lb. and ½ lb. Packets.

Patent Refined Isinglass. Sold in 1 0z packets price 1 / -

Patent Isinglass. Sold in 1oz packets. Price 8d.

FAMILY JELLY Box. Contains sufficient materials for making 12 Quarts of jelly. Price 7s. 6d. each

These give a good idea of the range of prepared gelatins available throughout the Victorian and Edwardian periods. In addition, flavoured packet jellies were being produced by a number of major companies which had now developed many other new and relatively instant foodstuffs. These were to meet the demands of hard-pressed housewives who, through the diverse effects of industrialization, frequently lacked the time, money and domestic skills required to make dishes in the traditional way. Bottled sauces, gravy brownings, custard and blancmange powders all helped, as did pre-flavoured and sweetened packet jellies. Many were manufactured by firms which became household names from the late Victorian period, through to the present time. They included Alfred Bird & Sons, Chivers, William P. Hartley, Pearce, Duff, Rowntree and W. Symington, among others. Slabs of concentrated jelly which had only to be dissolved in hot water before moulding had been introduced by the 1920s. In 1932 Rowntrees moulded them into cubes. Other makers followed their lead, jelly cubes rapidly becoming the standard form in which prepared jellies were sold to the public throughout the twentieth century.

Given all the technical advances of the last two hundred years, it might be thought that nothing could be easier than to buy a packet jelly, dissolve it in water, pour it into a mould, leave it to set, and then simply turn it out. However, those who attempt to do so are almost certain to face failure and disappointment. The main problem is that most cube jellies made up with the specified quantity of liquid are far too weak to stand up. If made with half the specified amount of liquid, they might just stand up at room temperature, but then have flavours which are unpleasantly concentrated. The only solution is to dissolve additional gelatin in a little of the cold liquid before making up the jelly cubes with the remaining hot liquid.

TO MAKE A MOULDED JELLY FROM CUBES

| 1 pack jelly cubes | 1 pt / 600 ml liquid |

| 1–3 tsp / 2–4 leaves gelatin | |

Sprinkle then stir the gelatin (or cut the leaves into pieces) into 5 tbs of the liquid in a glass or clear plastic measuring jug, and leave to soak for 10 minutes. Stir to break up any lumps, add the cubes and half the remaining liquid and microwave for some 2 minutes, or gently heat in a pan, until completely dissolved. On no account must the liquid boil. Stir in the remaining liquid thoroughly, then set aside until cool, but not set, and pour into a prepared mould.

TO MAKE A MOULDED JELLY FROM GELATIN

Follow the recipe above, using 5 level tsp gelatin or 8 leaves of gelatin for each 1 pt/600 ml of liquid.

Many historic recipes give the quantity of gelatin in ounces. For these 1 oz/25 g represents 10 level tsp, or 15 standard 4½ x 3 in./11 x 7.5 cm leaves, both sufficient to set 2 pt/1.2 l of jelly suitable for moulding.

N.B. There is no such thing as a correct amount of gelatin to liquid. The main considerations to be made include:

Serving temperature. Jellies to be served in a warm room or on a hot summer’s day will require more gelatin. Similarly if they are to be served chilled, directly out of a refrigerator, less will be needed.

Size. Larger jellies need proportionately more gelatin.

Shape. Packet jellies will set in a dish, bowl or glasses without any additional gelatin. A greater quantity will be required if they are to be turned out as shallow mounds, but much more if from an almost vertical-sided mould.

Ingredients. Jellies including a large proportion of fruit purée or similar thickening additives will require less gelatin. Those including alcohol will require more.

If preparing jellies for a particular occasion it is always best to make one as a sample beforehand, and adjust the recipe accordingly.

Metal moulds such as those of copper, aluminium and tinplate require no preparation.

Moulds of glass, pottery and plastic tend to stick to the jelly, even if freshly-rinsed before use.

Their interiors should therefore be given the thinnest pos-sible coating of vegetable or walnut oil, or of butter, just before being filled with the cold but unset jelly liquid. If this is still warm, it melts the oil or butter, and absorbs it, rather than leaving it in place as a separator.

TO LINE A MOULD

For a number of recipes, particularly those of the Victorian period, it is necessary to line metal moulds with a ⅛ – ¼ in./3 –7 mm all-over layer of clear jelly. To do this, embed the mould in iced water, pour in about ¼ pt / 150 ml jelly (made with at least 5 tsp/8 leaves of gelatin to the pint), when just about to set, then rotate the mould at an angle, to coat both the walls and the base. If the first coat is too thin, apply another in the same way.

TO UNMOULD A JELLY

- If using a metal mould, dip it briefly into warm water, or rapidly revolve its exterior under the flow of warm water from a tap.

- For every mould, hold it open-side up in one hand, using the other hand to wet both the flat surface of the jelly and also the plate it is to be turned out on.

- Tilting the mould slightly to one side, use the fingers of the free hand to ease the edges of the jelly from the mould, all round.

- Slowly rotate the mould while tilting it further towards the horizontal, holding it in place with the free hand, until it has fully separated, and its full weight can be felt.

- Tilt the mould until almost upside down, still holding the jelly in place.Put part of the rim of the mould on to the plate, and slide away the fingers of the free hand, leaving the jelly to fall free onto the plate.

- Slide the jelly into position, holding it there if necessary for about one minute for it to absorb the water beneath it, and so set itself neatly in place.

- Other methods, such as covering with a plate, inverting, and shaking vigorously, or blasting the exterior with the flame of a blowtorch, as seen practised on television by Michelin chefs, are not to be recommended.

- Use a straw to suck up any surplus water or liquid jelly from around its base, leaving a clean line between the jelly and the plate.

When working with gelatin, the following points should always be considered:

- Never sprinkle gelatin into hot water, or it will form lumps which are very difficult to dissolve.

- Never pour hot, melted gelatin into cold liquid as it may form ‘strings’, always mix when tepid.

- Never use fresh kiwi fruit, figs or pineapple in jellies, since their enzymes will prevent them from setting. There is no problem if they are in the form of tinned fruit or pasteurized juice.

- Never heat gelatin in milk over around 70°C, or it will cause it to curdle.

- Never bring gelatin to the boil, as this weakens its gelling properties.

- Unmould jellies just before serving.

- Never allow a moulded jelly to fall below the freezing point, since the long ice crystals slice through the jelly, causing it to break up and collapse.

- Jellies are best stored in cool, relatively humid conditions and eaten within a day of unmoulding. Dry conditions or a draught can cause their surfaces to dry out and become tough. Jellies also provide an ideal environment for the growth of infectious cultures, and must always be kept in clean conditions. If they are to be stored in refrigerators or larders, or transported to a venue, it is best to stretch a piece of clingfilm across the top of the mould to prevent the absorption of odours, dust, etc., or drying out.

Using these instructions it is easy to produce reliable, clear jellies. However, it is always best to try a small batch of any manufactured brand of gelatin before making larger quantities. Some have a yellowish tint, for example, and others, especially the leaf gelatines, are usually crystal clear. Some are made from bovine, and some from porcine bones or hides. In 1996 both the Spongiform Encephalopathy Advisory Committee and The World Health Organization issued reports which confirmed that manufactured gelatins were all considered safe for human consumption. They are filtered, concentrated and sterilized at approximately 140°C before drying to maintain this standard.

In addition to the major forms of gelatin considered in this chapter, there were others of lesser importance, such as hart’s-horn and ivory gelatins, along with other starches and gums which were used to create moulded desserts. Their brief histories and methods of preparation will now follow.

(1) O.E.D. sv Gelatin.

(2) Barham, 22–23.

(3) Hieatt & Butler,I 26.

(4) ibid., II 36.

(5) ibid., I 56

(6) Hargreaves,244.

(7) Hieatt & Butler,IV 104.

(8) O.E.D. sv Jelly.

(9) Hieatt & Butler,IV 105.

(10) Austin, 25, no.cix.

(11) ibid., 37, no. xvii.

(12) Hieatt, 74–5.

(13) O.E.D. sv SoundI.2.

(14) O.E.D. svIsinglass 1.

(15) Dawson (1590),II 19.

(16) O.E.D. sv Jelly.

(17) Lamb, 30–31.

(18) Raffald, xii–xiii.

(19) ibid., xv.

(20) Informationfrom theMuseum of Building, Bath.

(21) Rees sv Isinglass.

(22) BL 1801 d 2(5), quarto advertisement.

(23) Howard, 1–2.

(24) Beeton, 708–711.

(25) Oldroyd, 1–2.

(26) Nelson, 3–4.