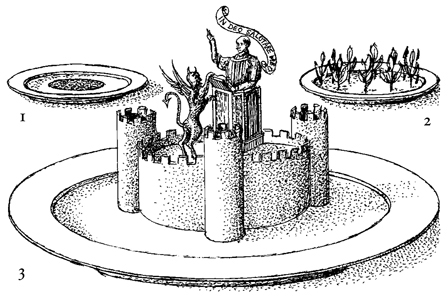

Figure 2. Medieval jellies. (1) a ‘partie jelly of two colours’; (2) a jelly garnished with laurel sprigs; (3) Bishop Clifford’s ‘brod custard with a castell, ther in with a stuff in the castelle of gille’, bearing a demon debating with a priest defended with the text ‘In Deo salutare meo’ (In God I have the advantage/benefit).

Since the conversion of raw materials into clear, flavoursome and attractive jellies demanded great investment in time, labour and skill, it is not surprising that they were considered a royal and noble delicacy. In the fourteenth century the finest foods cooked ‘for the kynge at home for his owne table’ featured a ‘potage callyd gele’ served at the start of the second of his three courses.1 Other recommended menus of the period included ‘gele’ as a second-course dish on Eastertime flesh-days, and as a first-course dish on fish days.2 The ‘Sotelteys’ which terminated each course at the King’s table were elaborate presentations of the finest foods, each being designed both to impress and to deliver a particular message through its symbolism or inscription. The Forme of Cury, the cookery manuscript compiled by Richard II’s cooks about 1390, gave instructions for making them, in various forms. The installation feast of Bishop Clifford of London in 1407 featured one with a demon and a doctor of divinity on a jelly-filled castle amid a custard moat, for example.3

Jellies continued to appear as second-course pottages in the fifteenth century, John Russell’s Boke of Nurture considering that ‘Jely red and white … is good dewynge’ for fish days.4 They were also to be found during the remainder of the meal, his menus including an amber jelly at the end of the second course and perch in jelly in the third.5 Unfortunately there are no descriptions of the second-course jelly which Henry IV provided for his French guests and the heralds after jousting at Smithfield, or for those served in 1403 at his marriage to Joan of Navarre.6 However, much more is known of those made for his successors. For the coronation of Henry V in 1413, the second-course pottage was a ‘gilly with swannys of braun {meat} ther in for the king and ffor other Estates’.7 The swans on this jelly lake were one of his father’s badges, a tribute which all the diners would have clearly recognized.8 When a feast was held to celebrate the coronation of his new wife Catherine of Valois in 1421 the second-course pottage was a ‘Gely coloured with columbyne floures’.9 The inverted flowers of the Aqualegia vulgaris resembled five doves clustered together, hence its ‘columbine’ name, meaning dove-like. Their appearance here therefore celebrated Catherine’s dove-like qualities of maidenly innocence and gentleness. Henry VI also had a second-course jelly at his coronation feast in 1429, his being a ‘Gely party wrytlen and noted with “Te Deum Laudamus” {Thee, God, we praise}’.10

Evidence of the importance of jellies at medieval feasts is provided by the accounts of the food served at the 1466 enthronement celebrations for George Neville, Archbishop of York and Chancellor of England, in his palace just to the north of York Minster. The menus for the various tables list tench in jelly, ling in jelly, ‘Jelly, and parted raysing to pottage’ and great jellies. Probably in addition to these there were a thousand dishes of plain jelly and a further three thousand ‘parted’ or multi-colour jellies, perhaps over five thousand jellies in all for a single feast.11

The earlier recipes for jelly are for an uncleared, meaty dish we would now recognize as a brawn. The following example dating from around 1381, could also be made with pig’s ears, partridges or chickens.

TO MAKE A JELLY12

{see fig. 2.2}

| 4 pig’s feet | ½ pt / 300 ml white wine vinegar |

| ½ tsp ground cinnamon | ½ tsp ground galingal {or ginger} |

| ½ tsp ground cloves | large sprigs of laurel or bay |

Soak the feet in cold water for a few hours, scrub clean, rinse, and chop coarsely. Cover with water, cinnamon, clove and vinegar, cover, and simmer slowly for 4–5 hours until the flesh falls off the bone. Pour the stock off into a clean pan, remove all the flesh from the bones, carve it in small pieces, return to the stock, briefly re-heat it and pour into a deep serving dish. Sprinkle the galingal over the surface, leave in a cool place to set, and finally stick with ‘branches’ of the laurel or bay (do not forget that other laurels than bay laurel are poisonous if eaten).

By the fifteenth century rather more elegant and delicate jellies of meat were being made by cooking calf’s feet separately in the stock in order to extract their gelatin. This may still be done today, but in the recipe below modern gelatin has been used to obtain exactly the same result.

JELLY OF FLESH13

| 1 rabbit, prepared for cooking | 1 bottle {sweet} red wine |

| 1 small ‘oven-ready’ chicken | gelatin |

| 1 lb / 600 g lean pork | salt |

| 1 lb / 600 g kid {or lamb} | {red} wine vinegar |

Joint the rabbit and chicken, and cut the other meats as for a stew, put into a pan with the wine, adding sufficient water to cover the meat, cover, and simmer gently for about 1 hour until tender. Pour the stock off {through a strainer} into a clean pan, and set aside. Dry the meat on a cloth {or paper kitchen towel} and arrange in a dish {for today’s use, the bones may now be removed}. Take the fat off the stock. Measure the stock and stir in 5 tsp/7 leaves of gelatin to each 1 pt/600 ml, pre-soaking this for 5 minutes in a little cold water before adding. Stir over a gentle heat until the gelatin has completely melted, add salt and vinegar to taste, pour over the meats in the dish, and leave to cool and set. Just before serving it may be garnished with pared ginger.

The same methods were followed when making fish jellies for fish days, the place of the calf’s-foot gelatin being taken by that obtained from ‘barbell or congure, playc or thornebake or other good fisch that wil agely & … the skynys of elys’. Here these are replaced by gelatin.

JELLY ON FISH DAYS14

| 2 lb / 1 kg pike, tench, perch, eel | {white} wine vinegar |

| 1 bottle {sweet} red wine | gelatin |

| ½ tsp crushed black peppercorns | a few blanched almonds |

| large pinch saffron | whole cloves & mace |

| salt | a piece of root ginger |

Cut the fish into small pieces, having first removed the skin of the eel and set it aside. Simmer the fish and the eel skin in the wine for about 10 minutes until tender. Strain the stock through a cloth into a clean pan, remove and discard the skin and bones from the pieces of fish. These you arrange in a large dish and leave to cool. Simmer the stock for 5 minutes with the saffron and the peppercorns tied up in a small piece of muslin, then add the salt and vinegar to taste. Remove the pepper, and measure the stock, stirring in 5 tsp/7 sheets of gelatin to each 1 pt/600 ml, pre-soaking this for 5 minutes in a little cold water before adding. Stir over a gentle heat until the gelatin has completely melted, pour over the fish, leave to cool, and just before setting insert the almonds, cloves and mace. Finally garnish with the little pared root ginger just before serving.

As a further development, the pig’s feet, calves’ feet and gelatinous fish were first used to make a rich stock which was used as the cooking liquor for the main meats or fish. This is an example of around 1420.

JELLIES OF {PORK & CHICKEN} MEAT15

| 6 pork chops | {white} wine vinegar |

| 1 small trussed chicken (if possible with the feet on) | |

| 1 ½ bottles {sweet} white wine | salt |

| 10 tsp / 12 leaves gelatin | a few blanched almonds & whole cloves |

| pinch of saffron | a piece of root ginger |

| ½ tsp ground black pepper | |

Trim most of the fat from the chops. Place in a pan with the chicken, wine and gelatin (pre-soaked in ½ pt cold water). Cover, gently simmer for about 1 hour until tender, remove the chops and arrange in one dish, the chicken in another. Skim the fat off the stock, add the pepper and saffron, simmer for a further 5 minutes, add vinegar and salt to taste, then strain through a cloth into a clean jug. When nearly cold, pour over the chops and the chicken, leave to set, then garnish with the almonds, cloves and pared ginger.

None of the jellies just described conform to our modern perception of what they should be like, since they contain meat or fish and have a predominantly sweet-and-sour taste. There were others, however, which were sweet, coloured and separated from any form of flesh, these being the ancestors of all later jellies. Some were flavoured and turned opaque white with almond milk, their appearance as a ‘white food’ giving them the title of ‘blanc-mange’ in the Stuart and Georgian periods.

ALMOND MILK16

| 3 oz / 75 g blanched almonds | ¼ tsp salt |

| 1 tbs sugar or honey |

Scald the ingredients with 1 pt / 600 ml boiling water, cover, and leave to cool for 1 hour. Strain off the almonds (saving the liquid), and either pound in a mortar or grind in a food processor with a little of the liquid to produce a smooth paste. Add the remaining liquid, pound or grind once more, then strain off the milk through a piece of freshly-rinsed muslin, squeezing it to produce about 1 pt/600 ml of almond milk. When stained with a variety of colourings, almond-milk jellies were used to make ‘parted’ jellies, as served at the Neville feast. Here again gelatin has been used to replace those originally based on pig, veal or chicken stocks.

PARTED JELLY17

{see fig. 2.1}

| 1 pt / 600 ml almond milk | 5 tsp / 7 leaves gelatin |

| 2 tbs sugar or honey | 4 oz / 100 g pastry |

| purple (turnsole), blue (indigo), red (alkanet), or yellow (saffron) food colouring |

Sprinkle and stir the gelatin into the almond milk for 5 minutes in a pan, add the sugar or honey and heat while stirring until it is dissolved. Roll the pastry into a narrow strip and use to form a circular wall, fixed securely in the centre of a dish. Pour half the white jelly around the wall, leave it to set, remove the pastry, then melt and colour the remainder of the jelly and, when almost cold, pour it into the centre. Alternatively, both the middle and the outer jellies may be coloured.

VYAUNDE LECHE18

| 1 pt / 600 ml jelly made as in the recipe above | |

| ¼ pt / 150 ml sweet {red?} wine | 1-2 tbs sugar |

| ¼ tsp ground ginger | red food colouring |

Pour half the jelly into a dish and leave it to set, then melt the remainder, colour it red, allow to cool, and pour on top. Simmer the wine, ginger and sugar together for 5 minutes, allow to cool, and pour over the jellies when they are fully set.

If the almond-milk jelly was made from fish stock, it could be served on fish-day meals. One recipe for ‘Brawn ryall in lentyn’ describes how the jelly was to be made by soaking the swim-bladders of dried stockfish and changing the water twice. After being laid on a board and scraped with the edge of a knife, they were washed, boiled, re-boiled in conger or eel stock, and ground smooth with almonds and cooked eel to make a delicate white brawn. This was used to half-fill eggshells, saffron-coloured ‘yolks’ of the same mixture then being added, and finally more of the white to make a realistic looking egg. The conceit might then be completed by serving them in salt, or on ‘cryspes’, crunchy strands of deep-fried batter closely resembling straw. Alternatively, the eggs could be made entirely from jelly, as in this version of ‘Eyren Gelide’.19

JELLY EGGS

1 pt / 600 ml jelly made as in the parted jelly recipe above but with an extra 1 ½ tsp / 2 leaves of gelatin.

Take the tops off eggshells, pour out the contents and use for any other purpose. Wash out the shells, fill them with the jelly, and prop them upright until set. Remove the shells and stand the ‘eggs’ on a plate. {The recipe is unclear, but the tops of the eggs appear to have been stuck with gilt-headed cloves}

The fifteenth century also saw fruit juices being turned into jelly-like leaches by the use of amydon, the very fine wheat starch, or rice flour.

STRAWBERRY

| 8 oz / 225 g strawberries | ½ tsp mixed ground pepper, ginger, |

| ¼ pt / 150 ml almond milk | cinnamon and galingal |

| 3 tbs red wine | 1 oz / 25 g currants |

| 3 tbs cornflour (for amydon) | 2 tsp {red} wine vinegar |

| 4 tbs sugar | red food colour (for alkanet) |

| 1 tsp lard | 1 pomegranate |

| large pinch saffron |

Pulp the strawberries with the wine and rub through {a sieve or} a piece of muslin. Stir in all but the vinegar, food colour and pomegranate seeds, and simmer while stirring for 5 minutes until thick. Remove from the heat, stir in the vinegar and suffi-cient food colour to produce a fine red. When cold drop it in spoonfuls on a dish and sprinkle with the pomegranate seeds.

As these and other medieval recipes show, jelly was usually poured or spooned directly into any of the silver-gilt, silver and pewter dishes then in use in wealthy households. There might also have been dishes specially made for this purpose, one guild account of 1480 recording ‘9 dosen gely dishes’ for the use of its members.20

(1) Hieatt & Butler, 39.

(2) ibid., 40 (4), 41 (8).

(3) Warner, 4; Napier, 6.

(4) Furnival, 49, 51.

(5) ibid., 49–50.

(6) Napier, 4; Warner, XXXIV.

(7) ibid., 7.

(8) Hasler 8.

(9) Warner, XXXVI.

(10) Strutt II 103.

(11) Warner, 97–9.

(12) Hieatt & Butler,I 56.

(13) Hieatt 74 no.100.

(14) ibid., 76 no. 102.

(15) Austin, 25.

(16) Napier, 76 Hodgett 24; Austin, 96.

(17) Warner, 61.

(18) Austin, 27.

(19) Household Ordinances, 471.

(20) O.E.D. sv Jelly.