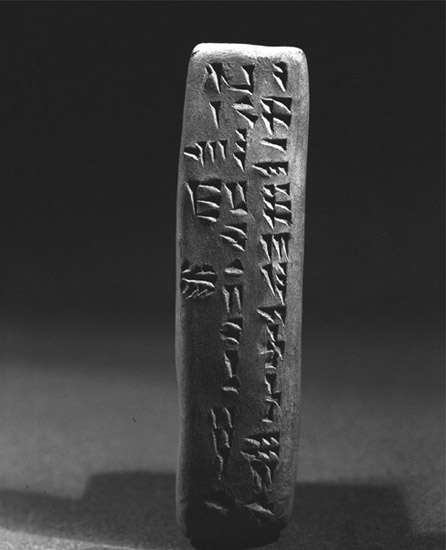

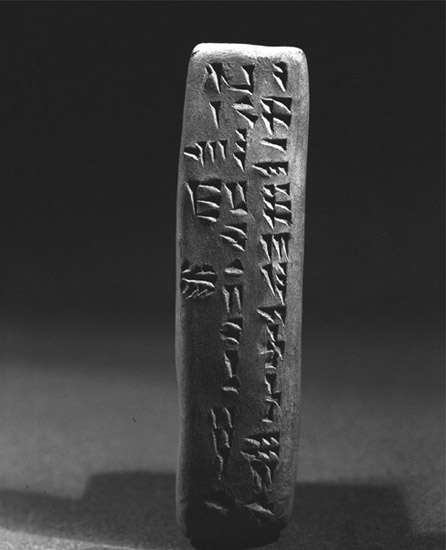

The ancestor to which all Western alphabets (although not all languages) can be traced.

The Phoenicians, who built a great trading empire throughout the Mediterranean in the second millennium B.C.E., created the alphabet—depicted here on a fourteenth-century B.C.E. terracotta tablet from Ugarit (now Ras Shamra, Syria)—on which our own is based. (The Art Archive/National Museum Damascus Syria/Dagli Orti)

Most of the world’s writing systems before the invention of the alphabet were pictograms, such as the Egyptian hieroglyphics. An alphabet is an important cultural innovation that allows easy and therefore potential mass literacy, more accurate record and contract keeping, adaptability to new intellectual concepts, and thus accelerated cultural change. The Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Arabic, and Cyrillic alphabets all derived ultimately from the Phoenician.

Phoenicia itself was a culturally united group of city-states clustered on a narrow coastal strip in modern-day Syria, Israel, and Lebanon. Its most famous cities were Sidon, Byblos, Tyre, and Berytus (now Beirut). The Phoenicians were renowned as traders, sailors, navigators, and craftsmen. The cedar forested slopes of Lebanon provided wood for seagoing vessels and served as a valuable trade commodity in itself. The organized, urban nature of Phoenician society allowed the development of technical expertise in many fields, including glass and dye. The word “Phoenician” comes from the Greek word for “purple,” a particular color of dye (derived from the murex seashell) that the Phoenicians traded throughout the ancient world.

Phoenicia, which emerged as a distinct entity as early as circa 3000 B.C.E., enjoyed its golden age from 1100 to 900 B.C.E., and finally disappeared into a succession of larger empires with the Assyrian invasion in the ninth century B.C.E. The area later came under Greek, Roman, Arab, Ottoman, and French rule before finally being broken up into the independent states of Israel, Syria, and most notably Lebanon in the twentieth century.

The Phoenicians traded throughout the Mediterranean world, coming into contact with virtually every civilization in ancient times. Because of their sailing ability, Phoenicians often started colonies in distant places. There were Phoenician colonies in Cyprus, Sardinia, Spain, North Africa (later Carthage), and probably in many other areas as well. The Phoenician alphabet was thus transmitted over a large area either by commercial contact or by way of Phoenician settlements.

While the Phoenicians were the first to widely transmit their alphabetic system of writing around the Middle East and Mediterranean world, the alphabetic concept itself originated at an earlier date. The alphabet’s origins lie in the Sinai peninsula with the Canaanites, a distinct ancestor of the later Phoenicians. As slaves of the Egyptians in both Egypt and the Sinai, the Canaanites encountered the concept of written language in Egyptian hieroglyphics. They set about trying to give their own spoken language a literate tradition.

Egyptian hieroglyphic symbols were used in the ancient alphabet, but only as mnemonic devices. For example, the letter A no longer stood for their word for “bull” (which started with the sound of “eh”), but simply the sound “eh.” This is called the acrophonic principle. It is important to note that alphabets are usually adopted to make a preexisting oral language literate. Therefore, the alphabet and language are not always of the same origin.

The ancient Canaanites eventually migrated to the more fertile regions of the Mediterranean coast, where they freely mixed with other peoples. By 3000 B.C.E., these peoples had coalesced into what we know as the Phoenicians. One of the cultural heritages brought to the large Phoenician identity was the ancient art of the alphabet. At first, the Phoenicians used a Babylonian-derived picture writing as well. It was probably the demands of commerce and contracts that brought the alphabet to prominence. The intricacies of trading and contract writing could easily overwhelm simple hieroglyphic systems. The earliest evidence for the Phoenician alphabet dates from the papyrus producing city of Byblos in the fifteenth century B.C.E.

The Phoenician alphabet consists of twenty-two characters, all of them consonants. The missing vowels are implied in the written language. Presumably, a native Phoenician speaker could recognize the full words from their context in the sentence. This system has the great advantage of being easy to learn and adaptable. Hieroglyphic writing systems required immense and often full-time study to master. Thus, only a few members of society became literate in non-alphabetic societies.

The Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet to their language sometime between 1000 and 800 B.C.E. According to the Greek historian Herodotus, Cadmus the Phoenician brought the alphabet to Greece with a group of Phoenician settlers. Despite the semihistorical nature of this account (several figures named are somewhat legendary), Herodotus is an overall good source of information about antiquity. The story may preserve a folk memory of a plausible event: a small Phoenician colony somewhere in Greece. Trade was another reason for Greek contact with Phoenicians. The existing evidence shows the Greeks beginning to use the Phoenician alphabet by the eighth century B.C.E.

Over time, the Phoenician alphabet gave birth to the Etruscan, Latin, Cyrillic, Aramaic, Arabic, and Ethiopian alphabets as well. The different peoples that adopted the Phoenician alphabet often included new modifications (such as including vowels) or new characters to reflect unique sounds. Different peoples preferred to read in specific directions, further affecting the local development of alphabets. Time and distance also altered the appearance of what was originally Phoenician script. All these reasons account for the distinctly different appearance of, for example, Arabic and Latin. Even Germanic runes, which came into being only in the first century C.E., are derived from a South Alpine alphabet, which itself is ultimately descended from Phoenician script.

Charles Allan

See also: Alphabet, Aramaic; Alphabet, Cyrillic; Alphabet, Greek; Alphabet, Latin; Greek City-States.

Bibliography

Albright, W.F. “Syria, the Philistines, and Phoenicia.” In The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 2, pt. 2, ed. I.E.S. Edwards et al. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975.

Aubert, María Eugenia. The Phoenicians and the West. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Markoe, Glenn. Phoenicians. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

O’Connor, M. “Epigraphic Semitic Scripts.” In The World’s Writing Systems, ed. Peter T. Daniels and William Bright. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.