A term that refers to a person who identifies him- or herself with the Arabic language and culture.

Some 1,500 years ago, the term “Arab” referred to those residing on the Arabian Peninsula. The inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula consisted of nomads (“Bedouins”) and city dwellers. Both of those groups were heavily involved in trade throughout the Arabian Peninsula, which served as a bridge between Africa and the East and between Eurasia and the South.

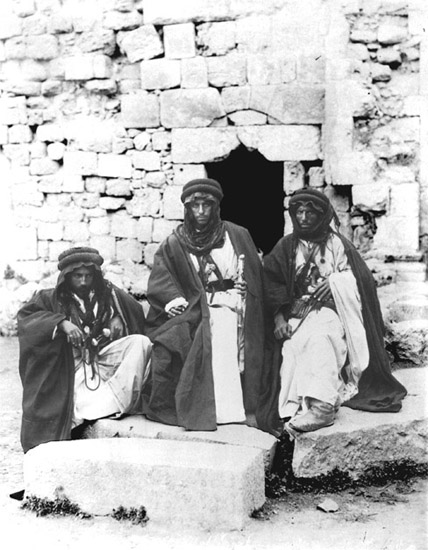

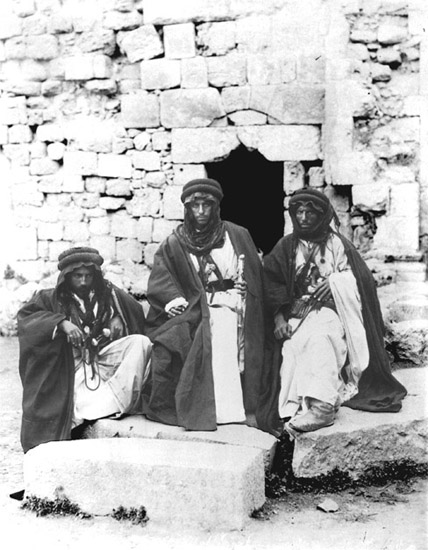

The Bedouins, being nomadic people, brought many goods from their travel routes, which included relatively faraway destinations. They also came in contact with other cultures and populations during these travels and trade. Aside from travel-stimulated trade, the Bedouins also robbed trade convoys on the peninsula. In fact, the rate of convoy robberies was a good measure of how strong the tribal leadership was.

The big cities on the Arabian Peninsula could be found on the coastline. Some of these cities relied on land trade (cities such as Mecca), while others focused on naval trade (such as Sanaa). Being located at a crossing point between Europe, Africa, and Asia, the Arabs became an important culture essential to the trade routes between Europe and Asia.

Arabs and the Expansion of the Islamic Empire

By the end of the sixth century, a new religion emerged in the peninsula: Islam. The expansion of Islam also meant the spreading of the Arabic language. The Islamic scripture, the Qur’an, was written in Arabic, and all prayers were in Arabic. Thus, a devoted Muslim had to be able to communicate in Arabic. In addition, the Arabs were the rulers of the Islamic empire in the first centuries of the expansion of the new religion. The new religion and the size of the empire had a tremendous impact on trade, which was regulated and unified across the empire.

The expansion of the Islamic empire and the culture of ancient Islam meant that the center of the affiliation circle was the religion rather than the ethnicity. The fall of the Abbasid empire in the thirteenth century and the rise of the Safavid and Mamluk empires meant that Arabs no longer controlled the Islamic empire, stretching from Northern Africa in the east to India in the West.

A nomadic Arab people of the Middle East, the Bedouins have been engaged in long-distance trade since ancient times. (Library of Congress)

For another 1,300 years following that period, most Arabs saw themselves as Muslims and only afterward as Arabs (some Arabs were Christian or Jewish). As a matter of fact, until the end of the nineteenth century, calling someone “Arab” was considered an insult, since “Arab” denoted simple nomadic people, the Bedouins. This changed when nationalism started to gain power over religion in the Arabic-speaking area.

Arab Nationalism and Trade

In the nineteenth century, the French, Italian, and British armies conquered most of North Africa, bringing the trade relations between Europe and this area even closer. By this time, Arabic was spoken as far away as Morocco and even in some sub-Saharan lands. What is now called the “Arab world” was formed.

Several factors contributed to the changes in the Arabs’ views and their self-identity as “Arabs.” First and foremost, the weakening of the Ottoman empire inspired the increasing process of disintegration. In Turkey, the heart of the empire, the “Young Turks” began to advance the idea of Turkish nationalism. The European forces, who were perceived as powerful foreigners, also strengthened the self-identifying process and unity in the Arabic-speaking areas.

Egypt was the center of Arab nationalism. The first sparks of Arab nationalism appeared when Napoléon Bonaparte took over Egypt in 1798. Following the French occupation, the British took over the country and the Ottoman rule over Egypt ended. Egypt was ripe to become an independent country and to secede from the Ottoman empire.

The establishment of the French army in Egypt was followed by the penetration of other European nations, because the merchants followed the armies. The Ottoman empire gave the European merchants special status, thus making it profitable for Europeans to trade in those lands (sometimes with no profit to the locals); this case was especially noticeable in Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon.

The Europeans not only influenced trade, but also other ways of living, such as politics. More and more people in the Arabic-speaking world started to think of themselves as Arabs in a national manner. Arab nationalism spread from Christians in Lebanon and liberals in Egypt to a growing number of Muslim Arabs.

The slow downfall of the Ottoman empire, which was increased by the end of the nineteenth century, brought a new secular flair to the Arabs: nationality. By the end of the nineteenth century, scholars from Lebanon and Egypt began to share ideas of Arab nationalism. The leaders of this movement were Arabic-speaking Christians who wanted to become more involved with the society and Muslims from Egypt.

A turning point was the fall of the Ottoman empire at the end of World War I. For the first time, the Muslims found themselves without a single Muslim empire (Persia and Turkey turned to secularity, and Egypt was occupied by Britain). Arab nationalism was spoken about freely and in the middle of the Arab world (in Palestine-Israel), the fact that a powerful Jewish-Zionist movement was gaining power made it even more likely for an Arab national movement to rise.

Post–World War II Arabism

The 1920s saw the rise of an Arab national movement and with it a rise of an alliance between the Arab nations in matters concerning trade and regulative policies. The Arabs participated in the boycott of colonial products (mainly British) in the 1930s and were actively supportive of their colonial regimes’ World War II enemies, namely, Nazi Germany.

After World War II, most Arab nations gained their independence and became sovereign. In 1945, the Arab League was founded and consists today of twenty-two members: Algeria, Bahrain, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

One of the first actions of the Arab League was to declare a boycott on trade with Zionists, later on Israelis, or any company who had any connection with Zionists or Israelis. More than sixty years later, this boycott still exists, operating from Damascus. However, the “Arab boycott” has proved ineffective. Israeli products can be found not only in Palestinian territory, but also in many other Arab lands under pseudonyms to mask the fact that they were manufactured in Israel. Only Egypt and Jordan have a peace agreement with Israel, so they do not obey the Arab boycott. Moreover, most international corporations are operating today in Israel (e.g., Microsoft, McDonald’s, Daimler-Chrysler, Intel, and British Airways, among others), and in a free economy the Arabs cannot afford to boycott these corporations.

Arab trade power grew dramatically in the 1970s when the world was introduced to the petrodollar. Although oil and gas were found in the Middle East in the beginning of the twentieth century, only after World War II did the Arab world become a significant producer. Until 1973, oil prices were relatively low, but by the end of the 1970s prices increased about 800 percent, making some Arab countries the richest on Earth. Oil and gas are major products for the following Arab states: Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Other Arab lands (like Jordan and Lebanon) benefit from the effect of this wealth as it flows into other Arab countries. Another influence of this wealth is the investments the nations make abroad and the fact that Arab traders can be found today outside the Arab world.

The growing population in the Arab world, combined with the fact that in some countries the living conditions are poor, add to the fact that Arabs make up a large percentage of the immigrant populations that arrive in Europe and the Americas. An important Arab nation in this matter is Lebanon. Lebanese traders can be found in the most remote places on Earth (it has been said that as many Lebanese live in Lebanon as abroad), and they use their Arabic connection to make a reliable network of trade across the globe.

Today, Arab trade is not as important as it was in the early centuries, but as time passes this nation of traders finds its way in the modern global village. However, the liberalization of the world economy and the frustration of those in the Arab world who feel as if they were left behind are contributing to a growing dissatisfaction, which has led some to support Islamic radicalism as an alternative to the Arab nationalist regimes.

Nadav Gablinger

See also: Mediterranean Sea.

Bibliography

Cameron, Rondo. The Concise Economic History of the World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Curtin, Philip. Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Issawi, Charles, ed. An Economic History of the Middle East. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

Lewis, Bernard. Race and Slavery in the Middle East: A Historical Enquiry. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Richards, Alan, and John Waterbury. A Political Economy of the Middle East: State, Class, and Economic Development. Boulder: Westview, 1990.

Tuma, Elias H. Economic and Political Change in the Middle East. Palo Alto: Pacific, 1987.