Part of the Mediterranean Sea between Greece on the west and Asia Minor on the east originally known as the Archipelago, a term that is now used for a series of any islands.

The Aegean Sea is bounded on the north by the European part of Turkey and connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Sea of Marmora and from there to the Black Sea through the straits of Dardanelles and Bosphorus. The main islands in the Aegean are Thásos in the north off Macedonia; Samothrace in the Gulf of Saros; Euboea along the eastern coast of Greece and the largest of the islands; the Northern Sporades, including Sciathos, Skopelos, and Halonesos, which extend from the southernmost part of the Thessalian coast; Skyros just to the northeast of Euboea; Lesbos, Chios, Sámos and Ikaria, Cos, and Calymnos just off Asia Minor; and the other islands of the Sporades; as well as the Cyclades, which include Ándros, Tínos, Naxos, and Páros. Most of the Aegean islands are actually prolongations of promontories of the mainland. The islands form two chains across the sea from Greece to Asia Minor, and many are in sight of other islands. The islands have fertile valleys that produce an abundance of agricultural items such as wheat, wine, mastic, figs, raisins, wax, honey, cotton, silk, and oil, as well as marine products such as coral, sponges, and fish.

Seafaring people arrived in the region of the Aegean Sea as early as 10,000 B.C.E., but most evidence points to 3000 B.C.E. as the beginning of active trade and development. The proximity of the islands facilitated sailing with simple technology. Aegean sailors sailed among the islands and slowly ventured farther and farther away from their homes. A major eruption of the Thera volcano in the second century B.C.E. resulted in the decline of the Minoan civilization and the rise of Mycenae. There is a wealth of archaeological evidence indicating that after the Trojan War Aegean sailors ventured into areas such as southern Italy, Sicily, Nice, and Marseilles. The expansion of trade coincided with the rise of Athens as a great city-state. The Aegean islands benefited from this trade because of their location.

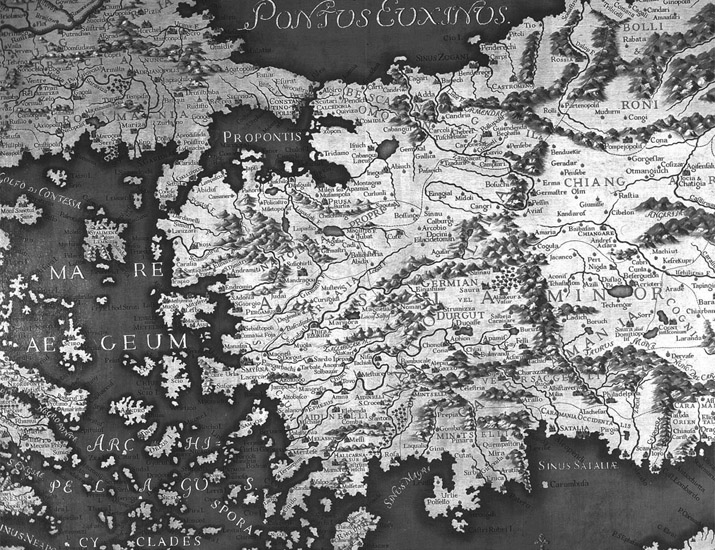

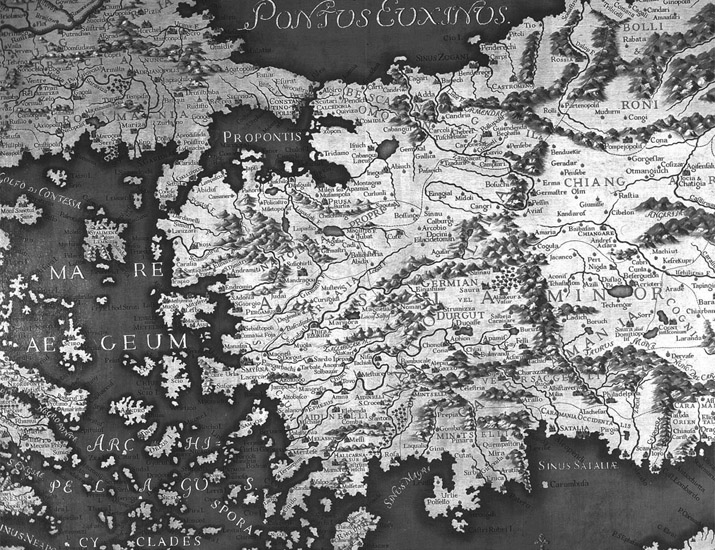

The Aegean Sea in the eastern Mediterranean has been a center of trade from ancient times to the present. This sixteenth-century map by Venetian cartographers Gian Battista Ramusio and Francesco Grisellini highlights the importance of the sea to that Renaissance kingdom’s economic well-being. (The Art Archive/Doges’ Palace Venice/Dagli Orti)

After the rise of the Roman empire, the islands took on added significance, especially after the establishment of the eastern capital at Constantinople. The Romans routinely imported wheat from Egypt to feed their population, and the ships had to pass through the Aegean to reach the imperial city. After the destruction of the Byzantine empire in 1453, the city-states of Venice and Genoa dominated the Aegean, and the traditional role of Aegean sailors and merchants was controlled by these new maritime powers. To survive, many Aegean sailors began smuggling goods or engaging in piracy.

Between 1453 and the mid-1600s, the Aegean people endured Italian rule until the Ottoman empire conquered the region. By the eighteenth century, many of the European states had come to appreciate the strategic location and importance of the islands. The British, Dutch, French, Turks, Russians, and Venetians attempted to gain the support of the local population by offering employment to the sailors, who were some of the best seamen in Europe. During the French Revolution, the Aegean sailors took over traditional French marine routes to Spain, carrying bulk produce such as grain across the Mediterranean. By 1804, these sailors had journeyed across the Atlantic and established trade in South America, this time exchanging wine for animal hides. During the Napoleonic Wars (especially from 1804 to 1814), the profits from trade allowed the Aegeans to build many new ships. The Greeks relied on the skill of Aegean sailors in 1828, when Greece declared its independence from the Ottoman empire. After the Battle of Navarino, with the assistance of Great Britain and France, the Greeks and the central Aegean islands won their independence. By the mid-1850s, the Greeks had turned to the use of steamships to modernize their fleet. The Hellenic Steam Navigation Company was formed and gradually replaced the sail vessels. The islands became the center of warehouses, brokerage offices, banks, shipyards, and insurance companies that specialized in marine insurance. The focus on merchant trade continued throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Aside from merchant trade, the Aegean islands attract thousands of visitors annually. Cruise ships travel from one island to the next or offer several stops on a voyage from Greece to Turkey. The geographic formation of the Aegean islands provides a picturesque scene, and the weather is mild year round.

Cynthia Clark Northrup

See also: Minoan Civilization; Mycenae.

Bibliography

Dickinson, O.T.P.K. The Aegean Bronze Age. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Figueira, Thomas J. Athens and Aigina in the Age of Imperial Colonization. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.