An exchange of goods between the Old and New Worlds that began with the voyages of Christopher Columbus.

Defining “Atlantic trade” is of paramount importance. When historians commonly refer to it, they nearly always mention the infamous triangle trade revolving around sugar and slaves. Such early-modern confines take us from the fifteenth to the early nineteenth centuries. But it is not as if sugar and slaves are the defining characteristics, rather, there are convenient lines of demarcation. Moreover, Atlantic trade does not merely encompass the trade between Europe and the Americas. Effectively, the origins of Atlantic trade begin with Portugal’s hesitant voy ages around Africa’s coast looking for gold and spices and spreading the Christian word of God. While Atlantic trade was an extremely lucrative and burgeoning process throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and still is today, its historical significance lies in its role in the establishment of interdependent global trade routes.

Therefore, the motives for discovery, colonialism, and the struggles that followed because of rivalries, the significant commodities of transatlantic import, the interrelatedness of trade within the Atlantic basin will be discussed. Each of these three themes was a casual factor in the development of a consistent Atlantic trade route. Accordingly, the connectivity of commodities, countries, and conceptualizations all fall under the aegis of describing the “Atlantic trade.”

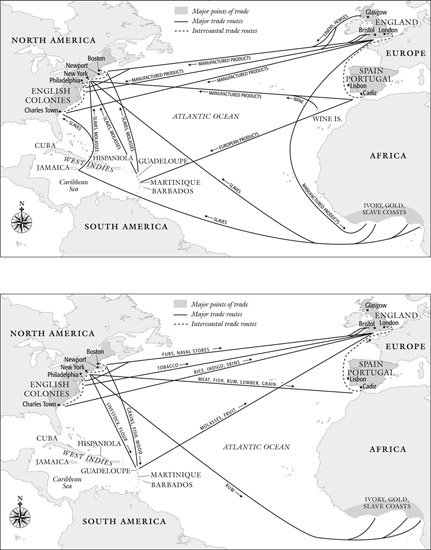

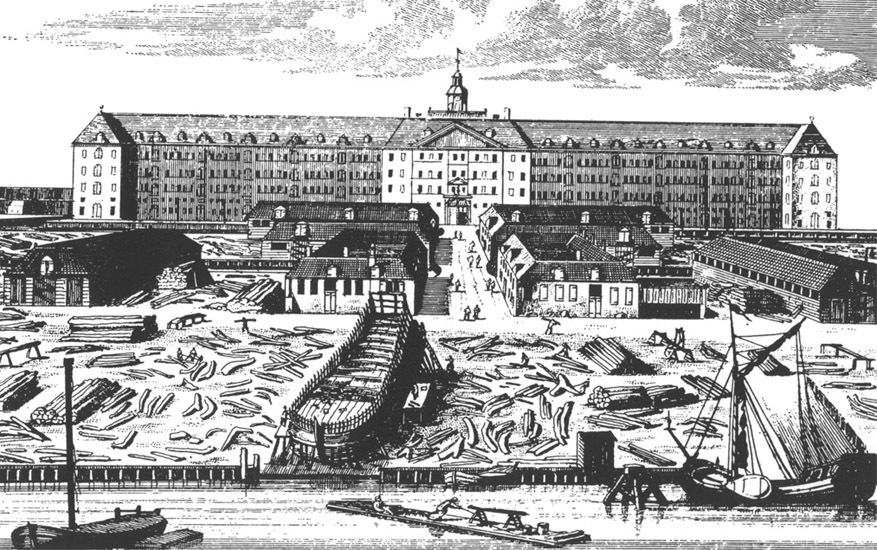

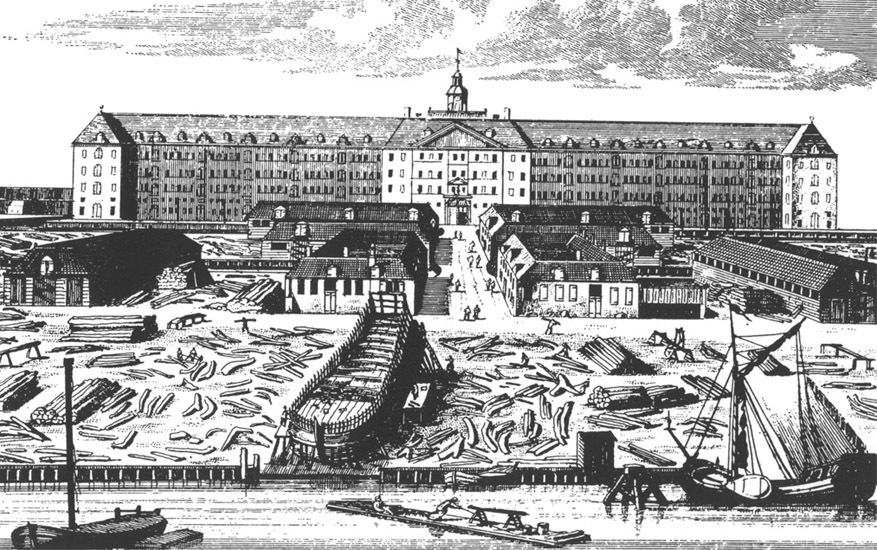

Transatlantic Trade, 1700 By 1700, the Atlantic Ocean hosted a web of trade routes between Europe, Africa, and the Americas. In general, manufactured goods originated in Europe and were transported to Africa and the Americas, while raw materials went from the Americas to Europe. Africa was a source of both raw materials and slaves. (Mark Stein Studios)

Portuguese

The origins of the Atlantic trade lie with Portugal’s fifteenth-century voyages of discovery. These voyages, which slowly expanded into the Atlantic and around the African coast, witnessed the evolution of the Atlantic from a highway between “Old World” destinations into a highway connecting new lands of economic opportunity. The new opportunities of the Atlantic emerged when the islands of the Azores, Canaries, Madeira, and Cape Verde became profitable ventures. In effect, the Atlantic islands were prototypes for the possibilities of exploration and even the plantation economies that rose to the fore throughout the “New World” by the seventeenth century.

These islands, which were discovered by 1460, were only a part of Portugal’s initial forays into the Atlantic (though it should be noted that Genoa participated heavily in the initial Canaries venture in the early 1300s). Yet, behind the discovery of the islands themselves, were larger and far loftier imaginings; specifically, the gold along the west coast of Africa that Europeans had known about for centuries because of its transmission by way of the sub-Saharan trades routes. Second, the Portuguese sought “Prester John,” a mythical Christian king to be found somewhere in Africa with apparently endless wealth and power who might help Europe fend off Islamic incursions. In addition, the glory of the nation could be advanced by any one of these discoveries, especially from the grandest prize: capturing the spice trade of the fabled Indies from the Arab middlemen of the Middle East.

What drove the Portuguese further at the end of the fifteenth century were the hopes of seizing the spice trade. For centuries the countries of the Levant, and the Venetians in particular, had been the sole brokers of the most lucrative products in Christendom: pepper, nutmeg, and cinnamon. After having secured access to the gold along the West African coast, Portugal continued to venture south along the African coast in hopes of finding a route to the East. When in 1498 Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope sailing toward India, it was the fruition of many highly concerted attempts to reach the Indies. But when the Portuguese arrived, they realized that India, between Europe and China, wanted for nothing. The ancient and complex Indian trading routes had long assured its wealthy minorities all their most sought-after commodities.

Spanish

Like Portugal, the other Atlantic European states ventured forth and accidentally created the Atlantic trade as a by-product of their quest to seize the fabled wealth of the Indies. Spain’s Christopher Columbus, England’s John Cabot, France’s Jacques Cartier, and the Netherlands’ Henry Hudson would all search for a way to the Spice Islands, and each failed. Still, in compensation, the New World was discovered/encountered. Subsequently, in light of the opportunities that were found, Spain’s acquisition of gold and silver mines and the possibilities for other lucrative goods, particularly sugar, trade routes were established to exploit the New World. Yet, it cannot be overappreciated that the impetus for the Atlantic trade lay in the hopes of Asia. Moreover, the Atlantic trade became a central cog in the Asian trade as well, since it was American and African bullion that often helped purchase Asian goods.

Once Asia’s role in the Atlantic trade is understood, one can begin to trace the complex political and economic events of the “traditionally” recognized Atlantic trades. Beginning with the discovery of the New World, a process known as the “Columbian exchange” began, wherein innumerable diseases, plants, and animals, not to mention minerals, began to be transferred from one side of the Atlantic to the other. The shipment of certain goods, namely, gold and silver from the plundered Amerindian empires of the Aztec and Inca and the subsequent conquered mines, began in earnest by 1531 as the Spanish laid claim to nearly all of Central and most of South America. Furthermore, the discovery that Amerindians were not a suitable workforce for Europeans because of their susceptibility to European diseases and the realization that they had souls lead to the mass transportation of Africans as a viable labor source for the Americas. Bartholomew de Casa argued vehemently in the first half of the sixteenth century for the souls of Amerindians and thus for their humane treatment. Consequently, alternative labor was sought, and since Africans had long practiced slavery and were familiar with European diseases, they became one of the most important parts in the Atlantic trade.

Portugal discovered in the sixteenth century that sugar could be grown in Brazil. Sugar quickly surpassed logwood (mahogany) in profitability and as its staple from the New World. But sugar cultivation was labor intensive and the Spanish realized that their need for workers could be met only by bringing African slaves to the New World. As the other European nations viewed the vast riches and opportunities that the Iberian nations had stumbled on, they began to actively look for the causal agent for the New World’s discovery, both the Northwest and Northeast Passages to the East. Furthermore, the political dynamics of the sixteenth century enabled England and the Netherlands to act on their desires since both had become Protestant nations hoping to defend their interests from the Catholic powers. Moreover, with the Hapsburgs firmly in control of both the northern and southern borders of France, France also was compelled to search for the exciting opportunities of the New World. The sixteenth century also saw the neophyte attempts of north European countries to explore the New World. Though because of the political exegeses, they aggressively sought to curb Iberian ascendancy by effectively supporting piracy against Spanish and Portuguese holdings in the Americas and Africa, and mainly in the Caribbean. Still, as the north European powers began to settle parts of the Americas, piracy’s preeminent role as northern Europe’s attempt to participate in the New World’s riches began to wane. By the dawn of the seventeenth century, the emergence of a fully functioning Atlantic trading schema was apparent, though halting and hesitant in parts.

Of course, 1492 represents an epoch in the history of the transatlantic trade, in that Columbus boldly set forth on his voyage to discover a passage to the East Indies, only to find two new continents, neither of which secured the coveted commodities of the Spice Islands of the East. Rather, the Spanish found mineral wealth. Particularly, the Spanish conquistadors found Amerindian empires rich in gold and silver, not to mention many precious gems like emeralds. Furthermore, the Spanish encountered various new fruits and vegetables that eventually enhanced the dietary lives of Europeans. By conquering the Aztecs and Inca in Central and South America, respectively, the Spanish were able to tap into preexisting trade routes that introduced them to a plethora of new items. Like their Portuguese counterparts in Africa, the Spanish found mahogany (logwood) growing throughout Central and South America, and more important they found various gold and silver mining sites. All these discoveries enabled the Spanish in the sixteenth century to surpass the might and wealth of the Portuguese and every other European power.

First seizing the Caribbean and securing the choice spots, the Spanish then spread through Central and South America. By the mid-sixteenth century, the Spanish had successfully surveyed the New World’s coast from the Chesapeake in North America all the way around South America to present-day northern California. Moreover, they had boldly ventured into the continents from present-day Colorado all the way down to the Amazon. The Spanish found that their European diseases decimated the natives and quickly sought to remedy the labor shortages of the New World by introducing African slave labor, a practice the Portuguese eagerly duplicated following their discovery and exploitation of Brazil in the sixteenth century. It would be the Spanish conquistadors, looking for Cíbola (the fabled seven cities of gold), who spread the diseases that decimated the local peoples of the Americas, and they, too, introduced the horse and wheel to the Americas.

The importance of the Spanish in the creation of the Atlantic trade routes is similar, but more direct than that of the Portuguese. In was the incredible wealth that they reaped from the New World that invigorated the other Atlantic nations to attempt similar colonization efforts. Though the Atlantic nations still hoped to find a more direct route to the Spice Islands. Moreover, the vast wealth of the Spanish Americas, particularly the Caribbean, offered choice hunting grounds for peoples and countries who were dissatisfied, envious, or even just criminally minded to make it rich by plundering the Spanish towns and ships. The Spanish offered the direct incentives for the creation of the Atlantic trade since they carried the pioneering efforts of the Portuguese to newer heights and, in regard to the Americas, were the first ones to establish consistent trading patterns connecting the Atlantic. In effect, African slaves and American gold and silver each symbolize the first real fruits of the Atlantic trade.

The origin of the Atlantic trade rests in the exploitation economies of the Europeans in the Americas. While European and Americans exchanged goods—iron, horses, muskets, gold, silver, and furs—the balance of trade was clearly in favor of the Europeans in terms of their exploitative results, particularly settlement. The introduction of Spanish settlements along the coastlines of the Americas established the final element in the Atlantic trade: the shipment of finished goods and European luxuries to the new colonizers. By the mid-sixteenth century, the pattern that would hold true until the dawn of the nineteenth century was established, in that goods from Europe, Africa, and the Americas were ferried among one another to different ports of call to complete an oceanic trade that became dependent on each of the continents. The trade was not a mere “triangle”; rather, the needs of the market dictated which part of Africa, Europe, or the Americas the trade affected. Still, the pattern was set; the needs of the Europeans and Africans were dependent on a global nexus, a global exchange of goods that included items from around the world.

In regard to the Spanish, their gold and silver mines produced the bullion that fed its revenues in Europe and paid for its luxury items. American gold and silver coinage found its way to the Indies, as Asian spices found their way to America. The interrelated trading routes of the modern world were forged with the opening of the Atlantic trades. Yet, it was in their success that the Spanish drew their harshest competition, in that, the Americas provided the Hapsburgs with the necessary capital for them to think that they could impose their will on their vassal states and others within Europe. As the political and religious affairs of Europe underwent basic changes in the sixteenth century, Spain was perched at the vanguard. As such, squabbles within its European empire, particularly, its inability to control the revolting Span ish Netherlands, led to the creation of one of the greatest maritime empires in history, especially in the seventeenth century: the Dutch. Moreover, the success of the Dutch in harming Spanish interests throughout the Atlantic emboldened the English to act similarly, which was interesting, considering that relations between the English and the Spanish steadily deteriorated throughout the sixteenth century. Effectively, by the dawn of the seventeenth century, Spanish successes and ineffectiveness helped to spur the rise of equally powerful competitors.

To understand the Atlantic trade, one must not merely chronicle commodity exchanges. Rather, the process in its entirety must be understood. Here then lies the basic importance of the rise of north European piracy in the Caribbean, since it was one of the means through which the Dutch, English, and the French matured as maritime nations. Not only did the rise of piratical raids offer the north European powers a chance to hone their skills, it hurt the Spanish by forcing them to take defensive measures, such as the ill-fated attempt to build a series of fortifications throughout the New World to prevent piracy. Piracy was not the only impetus for north European maritime communities to embark into the Atlantic; socioreligious turmoil also helped spur the Dutch, English, and French into the trades of the New World. Particularly, the revolt of the Spanish Netherlands in the mid-sixteenth century solidified Dutch aggressiveness, and Phillip II of Spain’s interests on the throne and the religion of England helped propel the English against the Spanish. The French, in a bid to counter the Spanish, also actively sought ways to assert their interests, although internal strife would hamper their efforts greatly until the mid-seventeenth century. Still, the climate in Europe nonetheless affected the New World, inasmuch as it propelled others to take an active interest.

Dutch

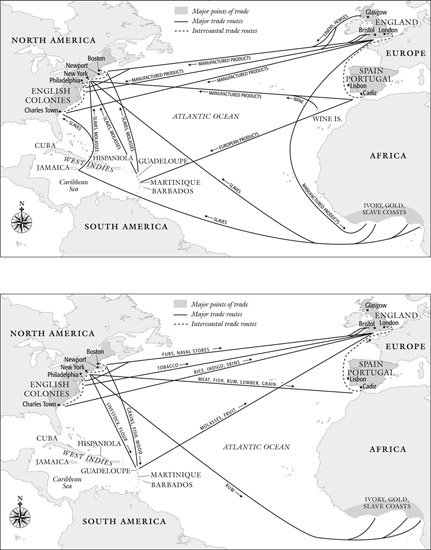

By the dawn of the seventeenth century, Dutch maritime skills had progressively advanced to rival and exceed those of Portugal and Spain. Particularly, Dutch charts and ship designs helped ensure that the Dutch could easily sail beyond European waters and aggressively compete against the Iberian powers’ interests. The classic example of Dutch prowess is embodied in the rise to dominance of the Dutch East India Company during the first half of the seventeenth century. In regard to Atlantic trade, the Dutch similarly displaced Portuguese interests throughout the South Atlantic, especially in both West Africa and Brazil. The Dutch interlopers of the sixteenth century solidified into the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company of the seventeenth century. Though the West India Company was never as fully successful as its Eastern prototype, nonetheless it did momentarily gain control of Brazil and its sugar crop and slave exports throughout the New World. In the Atlantic, however, the primary importance of the Dutch during this period rested on their aggressive tactics from ships that where more defensible than their Iberian counterparts.

Freed from Spanish rule in the late sixteenth century, the Dutch built one of the world’s great trading empires in the seventeenth century, spearheaded by the Dutch East India Company, whose Amsterdam warehouses and shipyard are shown here. (© North Wind Picture Archives)

The Dutch did not approach the New World like the Iberian powers; rather, they were more concerned with trade. As they maneuvered to dominate the Baltic and Mediterranean trades in the seventeenth century, so, too, did they attempt to control the new global trades connecting Asia, Africa, the Americas, and Europe. While successfully seizing the Baltic and the Asian spice trades, the Dutch struggled to control the Atlantic trades because of the highly competitive nature of the Atlantic trades. Nearly every nation by the mid-seventeenth century was attempting to acquire some element of the potential trades of the “new” Atlantic. Effectively, rather than seizing the source, the Dutch became carriers, or transshippers, of items for whomever they could once their initial dreams of conquests failed. Though they gained control of Brazil, the Dutch were repelled shortly thereafter. More important, however, the Dutch became the primary shippers of Portuguese goods throughout the Atlantic afterward. Furthermore, the Dutch maintained a large presence in the budding English colonies of the Caribbean and North America. Eventually, the primacy of the Dutch and the threat they represented to English interests led to a series of wars, the three Anglo-Dutch Wars, that were fought in African, Asian, and European waters late in the seventeenth century.

English

The English, like their Spanish rivals, also established a significant colonial presence that provided them with an outlet for finished goods as well as for procuring New World goods. And like those of the Dutch, English maritime endeavors were greatly enhanced during a seasoning process against the Spanish during the sixteenth century. Yet, the English came late into the Atlantic trade and suffered a peripheral role until the end of the seventeenth century, when their colonial and commercial efforts were able to overcome the effects of the English civil war. Despite a promising start at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the ill effects of the English civil war crippled an early commercial success, though it was during this time that the colonies in the Americas began to perfect their commercial endeavors and to stabilize. Also, throughout the seventeenth century English maritime industries developed, so that by the eighteenth century England was the undisputed naval power in the world.

By the 1670s, English interests had successfully woven the Atlantic into a stable trading relationship, with England at its center. Returning Asian goods would be processed into desirable goods for the mature West African markets, wherein linens and ironwork would be traded for gold, mahogany, and slaves. It was not until the 1640s that African slavery in the New World had begun en masse, and not until the mid-1670s that English merchants began to replace the Dutch as the primary supplier of slaves to the growing plantation economies of the Chesapeake and Caribbean colonies. Once the Royal African Company of the 1670s became effective, thousands of slaves were shipped and traded for sugar and rum in the Caribbean, and for rice, indigo, and tobacco in the Chesapeake. The New England economies also partook in the Atlantic trade by first providing cod for slave consumption and then becoming a major intercontinental transshipper for English interests. New England’s commercial development as a trading center was directly facilitated by the passage of the various navigation acts in the seventeenth century, which all sought to eliminate the Dutch presence in the Atlantic trade.

Of course, like all the other colonial powers, England ingested the wares of the Atlantic and then refined them for European consumption and returned manufactured goods to be traded throughout its trading centers in the Atlantic. By trading in nails, glass, china, and eventually even tea, England became the entrepôt of the Atlantic, but first it slowly developed its skills and its colonies to both produce and buy its wares. The process reached its apparent zenith by the mid-eighteenth century, when the importance of the North American colonies led England into a global war with the French from 1754 to 1763. Though only after the successful American Revolution did English trade in the Atlantic truly begin to blossom. It is an ironic twist of fate that English trade doubled and continued to dominate in the newly independent United States and during the nineteenth century.

French

The last major player in the Atlantic trade was the French. Despite early exploratory voyages in the 1520s, the French did not truly begin to partake in the riches of the Atlantic trade until Samuel de Champlain’s colonizing missions at the dawn of the seventeenth century. Still, even with profitability being evident, the French colonies in the New World did not take off until mid-century, as French politics hampered efforts to exploit the New World. The French benefited from both North American furs and Caribbean sugar. The French, unlike their European rivals, actively sought peaceable trading relations with Native Americans, since the fur trade was dependent on their ability to access the interior lands. The importance, or effect, of the American fur crops was the nearly complete replacement of the traditional Russian fur trade with American furs. The pattern for many American goods, once they arrived, was to either replace the goals of existing suppliers or create whole new consumer patterns throughout Europe. The second major commodity to come out of the Americas was sugar. The importance of sugar to the French economy can be attested to by the fact that the sugar produced in Haiti was the major French cash crop that helped underwrite Napoleonic expansion.

While many other nations also participated in the Atlantic trade, the previously mentioned nations dominated the major commodity exchanges throughout the early modern period. And while the eighteenth and particularly the nineteenth centuries saw an increased marketplace, both in goods and trading zones, as South America became a much sought-after venue, the major European powers still dominated. Eventually, the United States also became a major player, though only as the close of the nineteenth century drew near. Still, there was another commodity explosion in the South Atlantic that included coffee, industrialization projects to help develop new markets—thereby witnessing vast capital transfers, not to mention whaling, and many other goods. Yet, all were still under the aegis of European colonialism, though indirectly, since the Americas slowly became independent throughout the nineteenth century.

Alistair Maeer

See also: British Empire; Slavery; United States.

Bibliography

Birmingham, David. Trade and Empire in the Atlantic, 1400–1600. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Liss, Peggy K. Atlantic Empires: The Network of Trade and Revolution, 1713–1826. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983.

Northrup, David, ed. The Atlantic Slave Trade. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2002.

O’Rourke, Kevin H., and Jeffrey G. Williamson. Globalization and History: The Evolution of a Nineteenth-Century Atlantic Economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999.

Pietschmann, Horst, ed. Atlantic History: History of the Atlantic System, 1580–1830. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 2002.