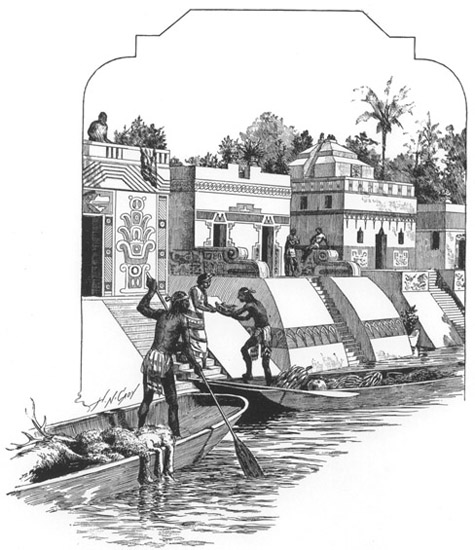

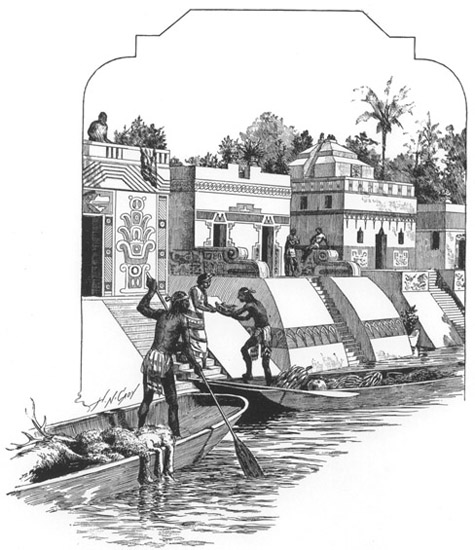

Although best known as a militaristic people, the Aztecs were also active traders, as this woodcut of pre-Columbian merchants on a canal in the capital of Tenochtitlán, carved in a much a later period, illustrates. (© North Wind Picture Archives)

The last Native American empire of the Valley of Mexico.

According to legend, the hummingbird god Huitzilopotchtli led the Aztecs out of seven caves called Azatlan somewhere to the north of the Valley of Mexico in the twelfth century. For some time, the Aztecs wandered from place to place, offering themselves as mercenaries to the many warring city-states in the area. Their god had promised that one day they would build a great city at a place where they saw an eagle sitting on a tree eating a snake. The city would itself become the capital of a great Aztec empire whose reign would last forever. In 1325, the wandering Aztecs spotted the promised eagle perched on a cactus in Lake Texcoco in the Valley of Mexico. Here, they built their great city called Tenochtitlán.

Primarily through war, but also through diplomacy and trade, the Aztecs built an empire that stretched west from the Valley of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean and east through the Yucatán peninsula to the Caribbean Sea. All the towns and provinces within the empire were required to send yearly tribute to Tenochtitlán. The tribute provided luxury items for the pipiltin (nobility) to maintain their status as the political, military, and religious leaders of the empire. The tribute also provided food for the macehualtin (common people), who worked as the artisans, farmers, and laborers of Aztec society. The yearly tribute included cotton and cacao beans from the lowlands along the Caribbean, gold and turquoise from the mines of Guerrero and Oaxaca, rubber, colored feathers, and jaguar skins from jungle provinces to the south, and corn, beans, and peppers from nearby towns. Tribute was also made in men, women, and even children, who were sent to Tenochtitlán to be sacrificed in the many temples at the center of the city.

Although best known as a militaristic people, the Aztecs were also active traders, as this woodcut of pre-Columbian merchants on a canal in the capital of Tenochtitlán, carved in a much a later period, illustrates. (© North Wind Picture Archives)

The Aztecs in turn traded goods produced by the macehualtin. Many of the macehualtin were peasants who raised corn, beans, and peppers on small plots of land owned by the pipiltin. Some farmers grew their crops on chinampas (floating gardens) made by building up islands of soil in the shallow waters of Lake Texcoco. Other macehualtin were artisans who made pottery, jewelry of gold and brightly colored feathers, and white cloaks made of cotton. Aztec farmers and craftsmen sold their goods in regional markets with the largest and most important one being held at a place called Tlatelolco. Here, more than 60,000 people gathered to buy and sell food, goods, and services. Long-distance traders known as pochteca brought luxury goods like amber, jade, and the emerald green feathers of the quetzal bird for the nobility to purchase. When the Spanish arrived in 1519, they marveled at the size of the market at Tlatelolco and the grandeur of the city of Tenochtitlán. Mesmerized by the wealth of the empire and horrified by the human sacrifice, the conquistadors recruited an army from among the many local tribes who resented the control of the Aztecs and destroyed Tenochtitlán and its empire in 1521.

Mary Stockwell

See also: Pochteca; Spanish Empire.

Boone, Elizabeth Hill. The Aztec World. Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 1994.