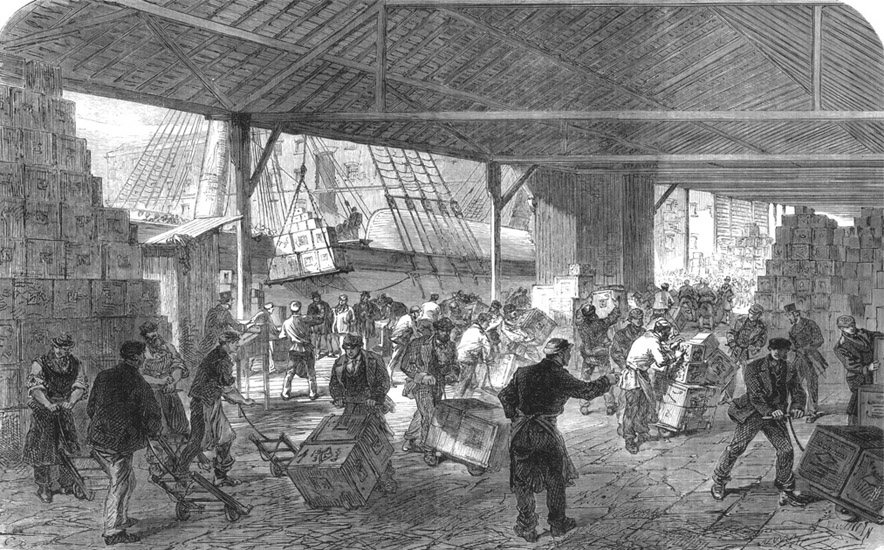

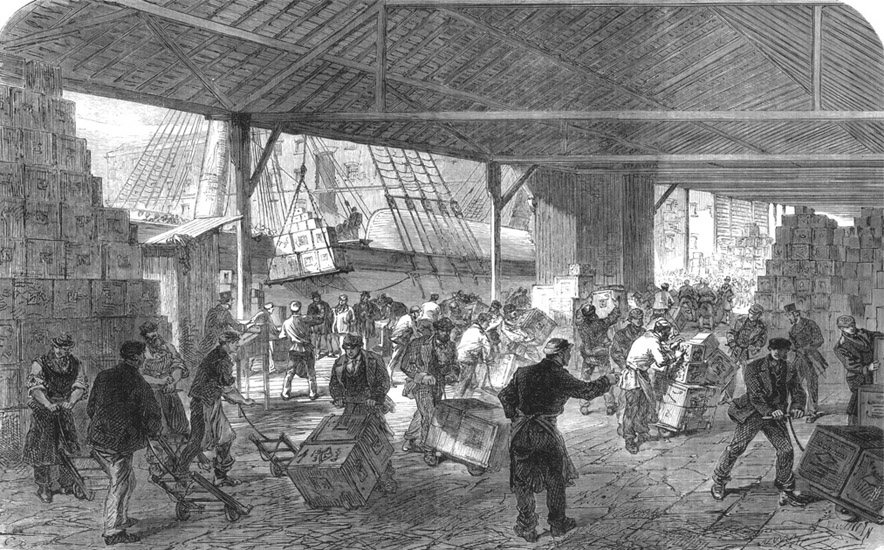

Among the most important commodities traded by the British East India Company was tea, seen here being unloaded at the company’s docks in London in the 1860s. (© North Wind Picture Archives)

A British company that traded with and eventually administered India between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries.

Among the most important commodities traded by the British East India Company was tea, seen here being unloaded at the company’s docks in London in the 1860s. (© North Wind Picture Archives)

The British East India Company was chartered on December 31, 1600, by Queen Elizabeth I as “The Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies,” a monopolistic trading body, during a period of rapid expansion of world trade. The company’s first voyage in 1601 to Amboia, India, brought back a cargo of pepper and was followed by a succession of trips in the ensuing years. In 1609, the first contact was made at Surat, where the Portuguese were established. The English were at first well received by the emperor of India, but the Portuguese intervened and ousted them. Two armed merchantmen returned in 1612 and helped establish a permanent English presence. Surat then formed the base from which the English expanded in the area—having to drive back both the Portuguese and then the French with diplomacy and force of arms—against both their rivals and the Indian rulers.

Initially, each voyage was subscribed separately, and although the returns were very high, this form of organization did not allow for the ex pansion of the capital base that was necessary to build the company. There was also competition from illegal English interlopers trying to skim some of the profits. This problem was not fully rectified until 1657 when at the end of the English civil war Oliver Cromwell supported the East India Company, reaffirming its charter. Even then there were continuing problems throughout the rest of the century as various groups sought to obtain some of the benefits for themselves.

The East India Company traded cotton, silk, indigo, saltpeter, and spices, which it paid for primarily with gold. Its activities were initially focused on India, but it also spread to the Persian Gulf and Asia.

The organization of the British East India Company was modeled on that the Muscovy Company, which had been chartered fifty years earlier. The East India Company gained a prominent role in 1689, when administrative areas called presidencies were established in Bengal, Bombay, and Madras. There was continuing competition from fringe ventures, which in 1698 were allowed to set up a formal competitor, the “English Company.” The original East India Company bought out this newcomer in 1702. In 1717, the company achieved a great success when it was granted a royal decree from the Mughal emperor exempting it from having to pay customs duties.

During the eighteenth century, the company’s power increased substantially, and it became as much an agent of British imperialism as a commercial venture, particularly after the victories of Robert Clive over the French at Arcot and Plassey (1757). In 1773, India was put under the rule of a governor-general. Toward the end of the century, the British government began to assume more direct control, and in 1784 the India Act created a new department of the British government to control the affairs of the company in India. This eventually grew into British administrative control over most of the Indian subcontinent. During the nineteenth century, the company expanded its activities to China, importing tea and paying for it with opium, which led to the Opium Wars. In 1858, the British government passed the Act for the Better Government of India, under which the British Crown took over all governmental responsibilities from the company. In 1874, the company was finally dissolved under the East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act.

Tony Ward

See also: British Empire; Indian Ocean Trade.

Tuck, Patrick, ed. The East India Company. New York: Routledge, 1998.