Medieval fortifications built by nobles and towns for protection against political rivals and invaders.

While castles drew on earlier forms of fortification from the ancient and classical worlds, medieval fortifications addressed changing strategic concerns with new defensive structures, especially in the emerging area of Europe. The gradual collapse of the Western Roman empire in the fifth and sixth centuries led to political instability and localism. City populations shrank and agricultural communities sought protection from local warrior nobles who could provide immediate protection, especially in their fortified homes. While Charlemagne forged an impressive empire that temporarily superseded regional concerns and reinforced notions of a common Europe, this imperial state quickly devolved into a series of competing kingdoms in the ninth century. Viking raids, Magyar incursions, and Muslim attacks hastened the collapse of centralized governments and brought about a hyperlocalism that favored the use of castles for protection.

Nobles throughout Europe built castles on their seigneurial landholdings, or fiefs, that they received from powerful upper nobility and royal families in exchange for feudal military service. Early medieval motte-and-bailey castles were often little more than wooden stockades perched on hilltops. Castles served as noble family residences, administrative and political centers, seats of justice, religious sites, and economic units that dominated the lives of peasants who lived in villages sheltered near the protection of castle walls. The seigneurial system of landholding and agriculture, known as manorialism, promoted an ideal of self-sufficiency—a seigneury was expected to produce everything necessary for the survival of its inhabitants through labor obligations. Medieval seigneuries gradually developed intensive agriculture techniques using a three-field system of crop rotation that increased yields considerably.

Keeps became the dominant fortified structures as castle builders turned to using stone in the tenth and eleventh centuries to build tall, fortified residences, often with towers. Warrior nobles favored keeps to protect their landholdings, while Christian clergy adopted fortified monasteries and churches to provide security against raids and invasions. Gradually, medieval architects began to construct larger castles, with concentric fortifications built around central keeps. The most significant period of castle building occurred between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries, as castle builders developed new techniques and borrowed fortification models from the Middle East during the Crusades. High medieval castles promoted economic growth by employing large numbers of masons, skilled artists and artisans, construction workers, and unskilled day laborers in huge construction operations that could last for decades. Major castle-building campaigns accompanied conquests, such as in Wales and in eastern Germany, and led to significant expansion of the three-field system of intensive agriculture.

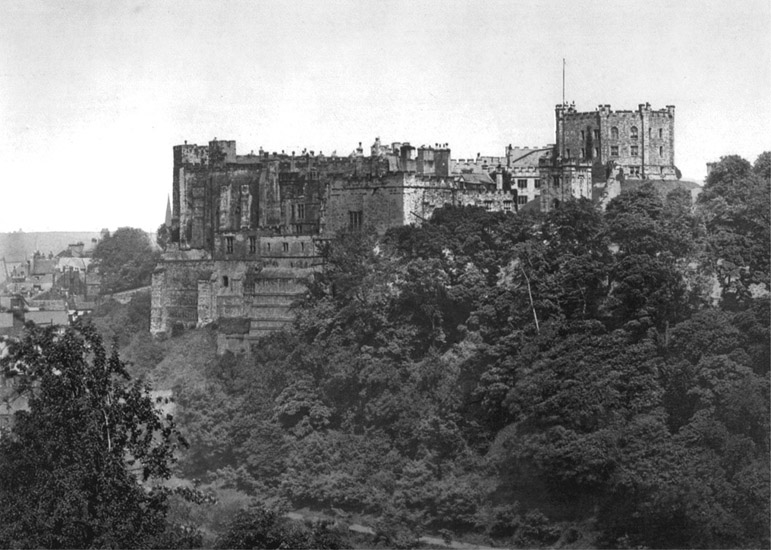

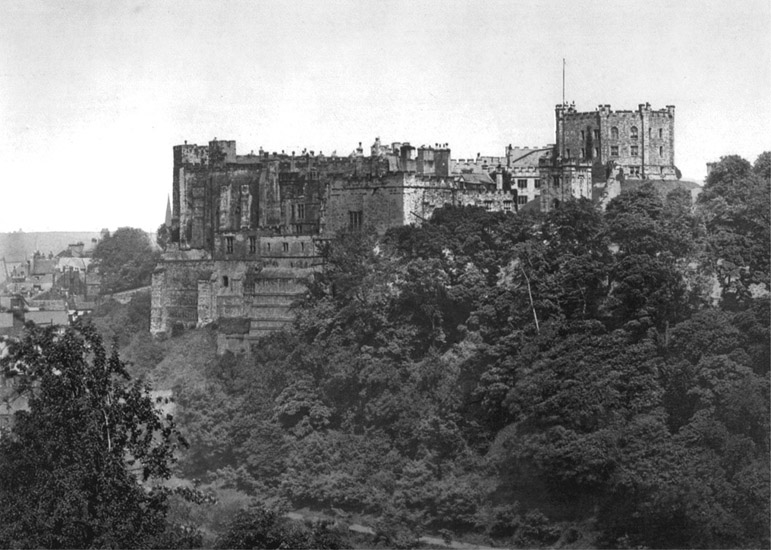

High medieval castles like this one in Durham, England, promoted economic growth by employing large numbers of masons, skilled artists and artisans, construction workers, and unskilled day laborers in huge construction operations that could last for decades. (Library of Congress)

European princes and nobles built castles to protect strategic sites and communities in their realms. The late Roman imperial ideal of defense-in-depth had led to the fortification of cities in many areas of Europe. Medieval architects often built on the ruins of these earlier Roman fortifications, adapting them or recycling stone for use in walls ringing small, densely populated medieval cities. The city walls of Constantinople were famous, but the fortified town of Carcassonne is one of the best remaining examples of high medieval urban fortification.

By the twelfth century, long-distance luxury commerce and local agricultural trade was being conducted in markets held either in city squares or near city walls. City gates controlled access to markets, redirected commerce, and influenced surrounding village networks. Castles and fortified towns could dominate the rivers and ports that were vital for commerce, imposing tolls and taxes. Lines of castle fortifications stretched across some regions, influencing commercial patterns and disrupting communications. But fortified cities also promoted long-distance spice and cloth trade by holding fairs, such as the Champagne fairs situated at fortified cities on the crossroads connecting north and south European markets.

As agricultural productivity led to population increases in the high medieval fortified castles, towns such as Paris had to build new systems of walls, and they frequently dismantled old fortifications. Obsolete fortifications could disrupt the development of cities when magistrates were unable to afford to get rid of walls that divided neighborhoods. Tenants occupied unused medieval walls, and portions of walls were incorporated into new buildings built in increasingly crowded faubourgs (early suburbs). Overcrowding of late medieval fortified cities left these urban centers highly vulnerable to diseases, such as the Black Death.

Brian Sandberg

See also: Gunpowder.

Bibliography

Bradbury, Jim. The Medieval Siege. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell, 1992.

Contamine, Philippe. War in the Middle Ages, trans. Michael Jones. Oxford: Blackwell, 1984.

Tracy, James D., ed. City Walls: The Urban Enceinte in Global Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.