Tribute System

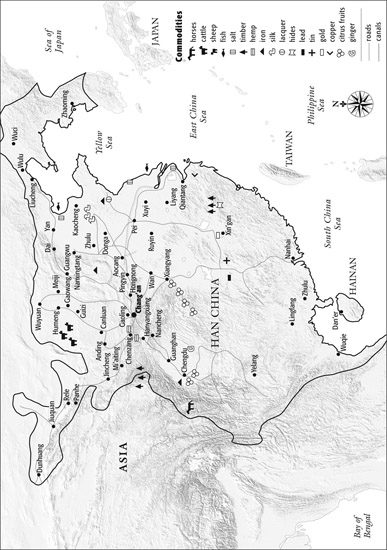

The tribute system, which was how China conducted trade relations with its neighbors, was clearly not a market-based exchange of goods. Its goals were to demonstrate the superiority of Chinese civilization and prevent barbarian attack. To accomplish these, the Chinese made trade a highly ritualistic ceremony in which they exchanged sophisticated luxury goods for everyday items that to them were of marginal value. From a business perspective, the Chinese were running a trade deficit. They gave items that had more value in their economy than the items they received. There was an exception to this in the tribute taken from some steppe nomads, who gave the Chinese higher quality horses than were typically raised in China. Outside of that, however, the tribute system was a ritualistic display of wealth that was in reality an uneven exchange of goods in favor of the tribute state.

Silk was the most famous product associated with China’s long-distance trade. Although it is difficult to pinpoint the exact beginning of the silk trade, it was well under way by the time the Han stabilized China. The Han silk trade exemplifies Confucian attitudes toward trade. It was totally state controlled. Every household was required to pay a silk tax to the government, giving the government control over most silk production and quashing any private-sector silk industry. The Han dynasty’s expansion into the central Asian steppe quieted trade caravan raiding nomads, allowing the famous Silk Road to flourish for much of the Han dynasty.

The period from the early 200s to the late 500s is the closest Imperial China came to losing its claim to continuity. For most of this period there were multiple centers of powers, however, they were all at least nominally Confucian. The chaos and constant fighting between these centers, along with the collapse of both Rome and Parthia into civil war and anarchy, caused a dramatic drop in world trade, especially in long-distance trade among civilizations. Steppe nomads, taking advantage of the chaos, moved in and blocked traditional trade routes like the Silk Road, and China’s involvement in world trade declined, as did the overall volume of world trade.

Kublai Khan (pictured here) completed the Mongol conquest of China, establishing the Yuan dynasty (1279–1356). Despite their traditions of subsistence and nomadism, the Mongols oversaw a revival of world trade. (© North Wind Picture Archives)

The Tang dynasty (618–907) was instrumental in pushing the steppe nomads back and restoring exchange among civilizations. In many ways, the Tang rejected Confucian tradition. They were the most warlike of China’s native dynasties and the early Tang rulers actively sought commercial and cultural interaction with other civilizations. The Tang’s aggressiveness made the tribute system harsher toward the tribute states, but long-distance trade and cultural exchange increased. Such policies came to a crashing halt with the defeat of the Tang by Muslim Arabs in the Battle of Talas (751). This defeat sent the Tang dynasty into civil war, of which steppe nomads, many of whom were converting to Islam, took great advantage by seizing control of the Silk Road and encroaching on China itself. As the dynasty descended into further fratricidal chaos, nomads gained control of much of northern China and Muslim traders began to dominate China’s long-distance trade.

Although other steppe nomads conquered much of China, the Mongols conquered them all. Kublai Khan completed the Mongol conquest of China, establishing the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368). Despite their traditions of subsistence and nomadism, the Mongols oversaw a revival of world trade. Collectively, Mongols ruled more of the world than any group before, putting much of the world economy nominally under one rule. More important, they strongly encouraged world trade. In part, this was done out of curiosity and a demonstration of power by the Mongol Great Khans; none dared to raid a trade caravan in his domain. The Mongols also used trade to staff the bureaucracies of their empire. The Mongols required some sort of administrative service from traders for them to trade in their domains. They did so because foreign merchants had little basis on which to unify with the people whom they administered and little incentive to see the trade promoting stability of Mongol rule shaken by revolt. Marco Polo is perhaps the most famous example of this to Westerners, but thousands of Buddhist and Moslem merchants had similar experiences. Unfortunately, the merchants also had no incentive to expend resources keeping up China’s infrastructure, leading to the unrest and revolt that toppled the Yuan and led to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).