An epidemic disease caused by Vibrio cholerae bacteria that spreads through contact with contaminated water, food, and feces, and colonizes the intestines producing severe diarrhea, massive dehydration, and sometimes death.

There is a historically intimate relationship between the diffusion of cholera, human migration, and the expansion of world trade. Until 1817, the world knew of cholera as the Asiatic epidemic. The geographic confinement of the disease changed with wars, conquests, and the intensification of Western market expansionism. London had two major cholera outbreaks during 1849 and 1854, Austro-Hungary in 1865, Russia and Prussia in 1866. The expansion of international trade contributed to the extension of cholera epidemic frontiers into Canada in 1833, Brazil and Montevideo in 1846, and Argentina in 1856. High death rates characterized all outbreaks.

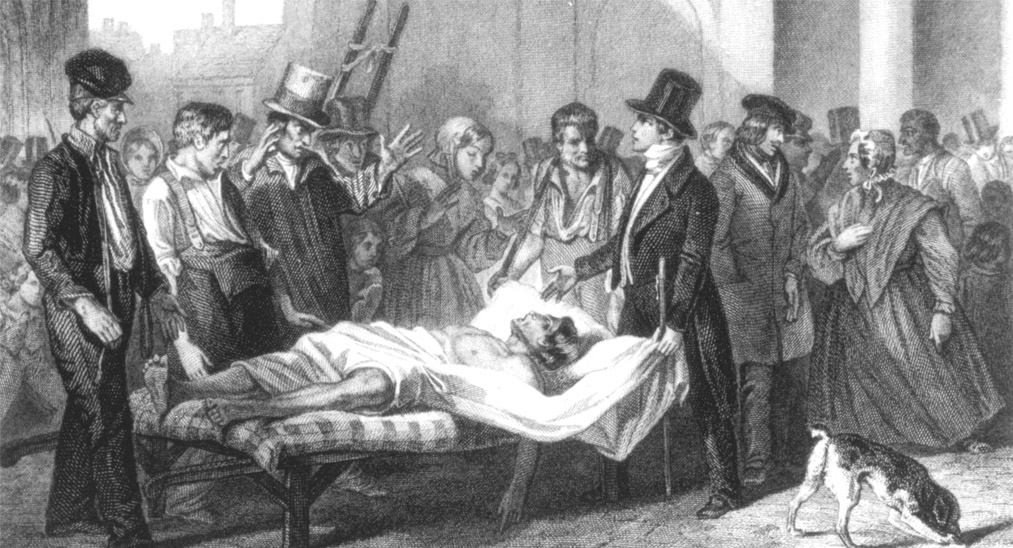

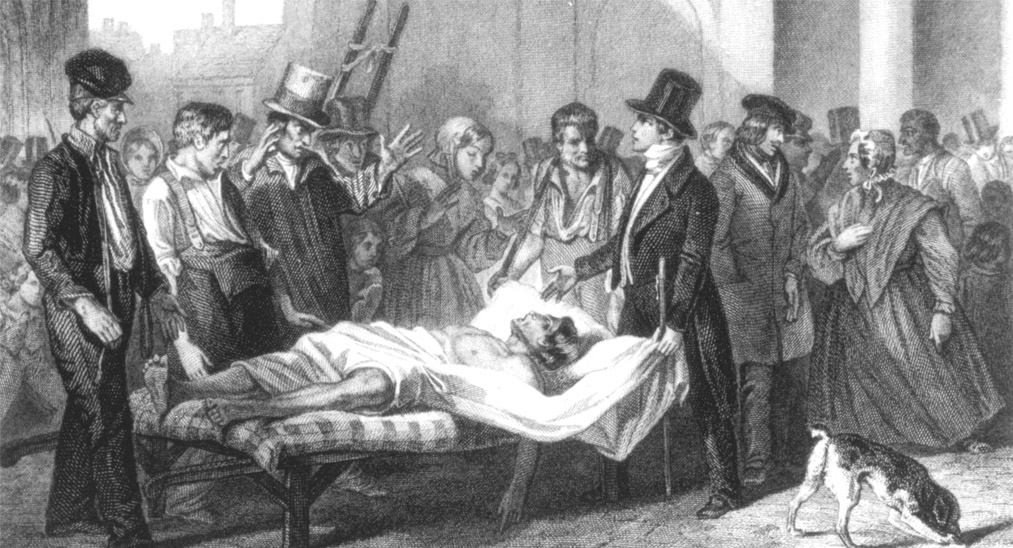

Amid the fear of contagion and death, cholera was instrumental in bringing about sociocultural changes concerning public policy and sanitary control of populations’ hygienic practices and living and working conditions. Notwithstanding the ports, where many trade-related activities took place, cholera remained largely uncontrolled due mainly to the resistance of owners and producers of export commodities in Europe and Great Britain in particular. Change occurred nevertheless. During the mid-nineteenth century, social medicine in Europe and preventive medicine in the United States emerged in a concerted attempt to apply scientific medical-bacteriological knowledge to political and social problems. In this process, international trade not only contributed to cholera transmission, but also to new approaches to social policy. Health care access became a right that nation-states ought to provide to all citizens. International trade also influenced the constitution of transnational sanitary networks. The inauguration in 1948 of the first World Health Organization office as an international health care coordinating and regulating body represents a substantiation of the transnational need for delineating mechanisms for an economy of social control of the working masses, mostly located in the urban and peri-urban areas.

Amid the fear of contagion and death, cholera was instrumental in bringing about sociocultural changes concerning public policy, sanitary control of populations’ hygienic practices, and living and working conditions. (Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine)

The twentieth-century Western world was cholera-free until 1990, when an epidemic outbreak occurred in Peru, thereafter rapidly expanding throughout the Americas. The epidemic outbreaks in the twentieth-century Americas coincided with another expansionist phase of the world trade, namely, globalization. Similarly as in the nineteenth century, the nation-states, social policies, and medical knowledge were changing. However, the public health system rather than being in expansion was in the process of contraction. Neoliberalism and the globalizing economies demanded private entrepreneurship, generally at the expense of the public sector outsourcing.

The twentieth-century cholera outbreak in the Americas affected the economy in various ways. It negatively influenced the process of import-export of agricultural and fish products, the tourism industry, and the activities of informal economy, in particular that of food street vendors. Yet, cholera positively affected the industries and commercial activities of water purifier and disinfectant products. Cholera also helped reinvigorate international trade and health agreements, such as the Second Argentinean-Bolivian Agreement.

Silvia Torezani

See also: Disease.

Bibliography

Foucault, Michel. Power. Vol. 3. London: Penguin, 1994.

Lima, Darcy. A pesar de todo… solo tiene cólera quien quiere tenerlo. Washington, DC: PAHO, 1997.