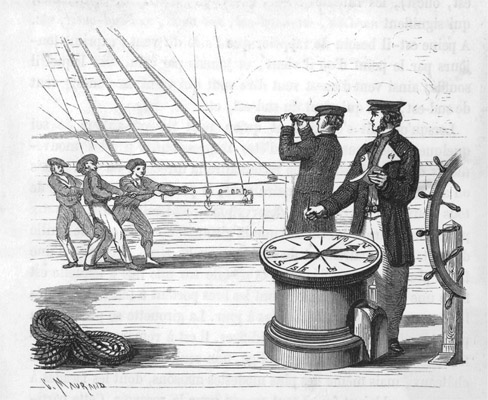

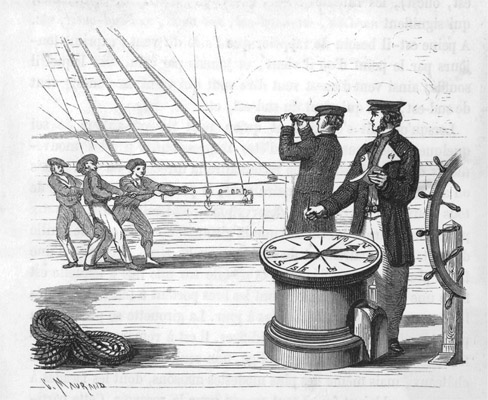

The compass, originally developed by Muslims in the Middle Ages and shown here at use on a nineteenth-century French ship, was critical for navigation and thus international trade. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

An invention capable of plotting accurate navigational courses independent of geographic landmarks or celestial sightings.

Before the compass, travelers navigated by the stars or by observing geographic points of interest. Either method severely limited the range and safety of travel. A cloudy sky could obscure the stars, while keeping to a checklist of known geographic points discouraged people from traveling to unknown regions.

The compass stripped away these limitations. Ships were freed from sailing along the coastline to find their way and no longer become lost while searching for stars on dark nights. Sailors could find their way even in winter, when bad weather obscured both the coast and the stars. This discovery opened the door to year-round trade and made possible the great sailing expeditions of the fifteenth century.

The compass, originally developed by Muslims in the Middle Ages and shown here at use on a nineteenth-century French ship, was critical for navigation and thus international trade. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

The first historical reference to a compass appears in a Chinese text dating to 83 C.E. It describes a spoon-shaped lodestone (magnetite) invention that pointed southward. By the eighth century, the Chinese were using magnetized needles instead of the lodestone.

These early compasses used a free-floating magnetized object, such as a needle perched on a platform of cork bobbing in a bowl of water, to indicate the direction of Earth’s magnetic poles. A variation was the dry-pivot compass, which suspended the magnetic needle in the air.

The first European reference to the compass appeared around 1190 C.E., when Alexander Neckam, an English scientist and abbot, wrote about a magnetic compass in a book about inventions. By the early thirteenth century, magnetic compasses appeared on ships. The device evolved to incorporate all east-west and north-south positions and wind directions.

Among the early practitioners of the compass was Prince Henry the Navigator, the son of King John of Portugal. Prince Henry founded his own commercial maritime enterprise and trained a cadre of seamen in the use of the compass. These men became stellar mariners. They were the first Europeans to sail around the African continent and map its features, a success that helped to clear the way for the African slave trade.

Other great Portuguese navigators include Vasco da Gama, whose 1497 expedition opened a trade route between Europe and Asia, and Ferdinand Magellan, whose expedition for Spain was the first to circumnavigate the earth.

The compass was instrumental in the rise of the Venetian Republic. By the early thirteenth century, using a combination of maritime prowess and crafty politics, the republic forged a monopoly on European trade from the east. Its dominance spurred other countries to seek alternative routes to the East. One of these was Spain, whose desire to circumvent the Venetians put Christopher Columbus on course to discover the Americas.

The magnetic compass operates on a scientific theory that the earth’s core consists of an iron mass surrounded by free-flowing iron liquid. The friction from movement of this liquid generates a magnetic field that pulls at a magnetized object. The direction of the earth’s true magnetic poles are not exactly aligned with the planet’s rotational axis, so a user of the compass must take this deviation, known as an inclination, into account.

Other types of directional compasses have appeared over time. A solar (or sun) compass operates much as a sundial does by indicating direction through the shadow cast by the Sun. Navigators used solar compasses in those areas where the earth’s magnetic field fluctuates, such as at or the near the magnetic poles or at high altitudes. The solar compass surfaced in the fourteenth century and is likely the invention of Syrian Arabs of Aleppo.

The gyrocompass uses a frame of spinning wheels, known as a gyroscope, that allows the device to maintain its altitude even while tilting in different directions, making it advantageous for ships and aircraft.

Hermann Anschutz-Kaempfe of Germany received a patent for the first working gyroscope in 1905. Elmer Sperry patented a gyroscope in 1911, and the two men fought bitterly over infringement. The gyroscope has since become a crucial instrument for guidance systems and mechanical stabilizers.

Ann Saccomano

See also: Exploration and Trade; Magellan, Ferdinand; Navigation; Portugal.

Aczel, Amir D. The Riddle of the Compass. New York: Harcourt, 2001.

Eyster, Bill. Thataway: The Story of the Magnetic Compass. Cranbury, NJ: A.S. Barnes, 1970.

Gies, Frances, and Joseph Gies. Cathedral, Forge, and Waterwheel. New York: HarperCollins, 1994.