There are four species of Zea native to Mexico and Central America.

Most scientists now believe modern corn descends from Zea mexicana, or teosinte. After domestication in the Balsas River basin of southern Mexico, Zea mexicana evolved into Zea mays, modern corn, or maize. The first archaeological record of Zea mays, a particular variety prepared as food by popping, comes from the Tehuacán caves near Puebla, Mexico, and is dated to 5,000 B.C.E. Corn’s use spread north, east, and west, becoming common in both temperate and tropical areas. By 3,000 B.C.E., corn was grown in coastal Ecuador, apparently spreading first to the Andean highlands, then by 1800 B.C.E. into the drier coastal communities of Peru, at the same time reaching New Mexico by 1,200 B.C.E. Although corn agriculture entered the Amazon basin slowly, it arrived in the Orinoco River basin between 400 B.C.E. and 100 C.E., roughly the same time it had reached the Mississippi River valley. Corn’s centrality as a food ensured it a place in Mesoamerican mythologies and religions, where it was seen as integral to all human life.

Different types of corn developed in Mexico or South America. Finds in pre-Columbian archaeological sites in North America and the Caribbean point to the fact that corn from Mexico and South America was traded along both land and sea routes connecting areas of sedentary and semisedentary civilization. However, the adoption of corn did not immediately connote the transition to a fully settled existence, as fields of corn were cultivated only periodically by nomadic hunter-gatherer societies, who relied on them as an occasional food source. In the American South-west and Eastern woodlands, for example, it took over a thousand years before corn became a staple food.

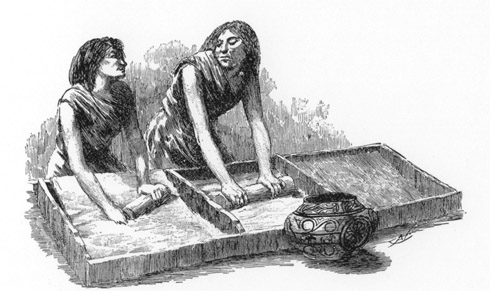

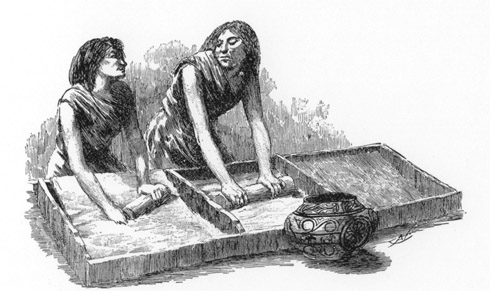

A key food source for ancient Americans, including these Anasazi women shown grinding the grain, corn became a widely traded international commodity following the European conquest of the Americas in the sixteenth century. (© North Wind Picture Archives)

Throughout the Americas, corn was cultivated in conjunction with other vegetables, as it is today, creating the corn-squash-bean food complex, a felicitous combination that prevented farmers dependent on corn from suffering pellagra, a disease caused by corn’s lack of lysine. On the other hand, pellagra became a problem in other parts of the world, particularly Europe, where corn was eaten unaccompanied by beans or squash.

After Christopher Columbus’s voyages, corn spread quickly to Europe and along maritime trade routes, connecting Spanish and Portuguese colonies with centers of population in Africa and Asia. Ironically, the introduction of cattle by Spaniards into the Americas in the colonial period ravaged teosinte corn in its native distribution as an understory plant in pine and oak woodlands. The hardy and fast-growing Peruvian strains of corn imported into parts of southern Europe flourished as a spring-summer crop and contributed to population increases in areas of northern Italy and the Basque countries of Spain and France.

Europeans and Africans cultivated corn in coastal settlements of West Africa and Angola by the first half of the sixteenth century. Corn’s spread was thus connected to the triangle trade based on slavery. By 1561, it was grown in Mozambique on the east coast, and by the nineteenth century it had supplanted sorghum as a food source in most of the wetter parts of sub-Saharan Africa. By 1543, the Spanish had brought it to the Philippine Islands and by 1590 Portuguese traders had introduced it into India. The Chinese-controlled maritime commercial network was responsible for corn’s distribution in Southeast Asia beyond European trade. Corn, however, did not supplant rice or wheat in Asia, but was adopted by mountain-dwelling agriculturalists on marginal soils where corn flourished, becoming the preferred staple of poorer regions and contributing to population growth wherever a wet season and warm temperatures allowed for successful cultivation.

Beginning in the nineteenth century, corn agriculture reached a new high in the appropriately named Corn Belt of the American Midwest. In 1933, farmers using mechanized agricultural technology turned to hybrid seed corn. It displaced old garden varieties completely by 1953, but this massive move unfortunately exposed the corn crop to devastating fungal diseases by the 1970s. More research developed newer strains resistant to disease in temperate North America and more productive corn for the tropics where it had become a staple food by the twentieth century. Corn’s introduction to tropical highlands and savannahs and to the grasslands and cleared forests of subtropical and temperate areas throughout the world has usually resulted in population increases because it is an extremely nutritious crop and can be stored dried or in powdered form.

Fabio Lopez-Lazaro

See also: Columbus, Christopher; Discovery and Exploration.

Bibliography

Bird, R.M. “Maize Evolution from 500 B.C. to the Present.” Biotropica 12, no. 1 (1980): 30–41.

Doebley, J. “Molecular Evidence and the Evolution of Maize.” Economic Botany 44, Supplement 3 (1990): 6–27.

———. “The Origin of Cornbelt Maize: The Isozyme Story.” Economic Botany 42 (1988): 129–131.

Pickersgill, B., and C.B. Heiser Jr. “The Origins and Distributions of Plants Domesticated in the New World Tropics.” In Origins of Agriculture, ed. C.A. Reed. The Hague: Mouton, 1977.

Sauer, Jonathan D. Historical Geography of Crop Plants. Boca Raton: CRC, 1993.

Simoons, F.J. Food in China: A Cultural and Historical Inquiry. Boca Raton: CRC, 1990.

Spencer, J.E. “The Rise of Maize as a Major Crop Plant in the Philippines.” Journal of the History of Geography 1 (1975): 1–16.