The generic term, from medieval times onward, for legislation regarding regulation of grain exports and imports in Britain.

The nature and impact of corn laws changed from the twelfth century onward, when they first appeared in the historical record. The initial formal legal ban on exports so as to maintain a low price for domestic grain in Britain was imposed as early as 1361. A series of laws followed—for example, in 1436, which granted grain growers monopolistic advantage, and in 1463, which in effect controlled grain exports and imports, dependent on the domestic price level, and imposed tariffs and duties on grain imports and exports accordingly.

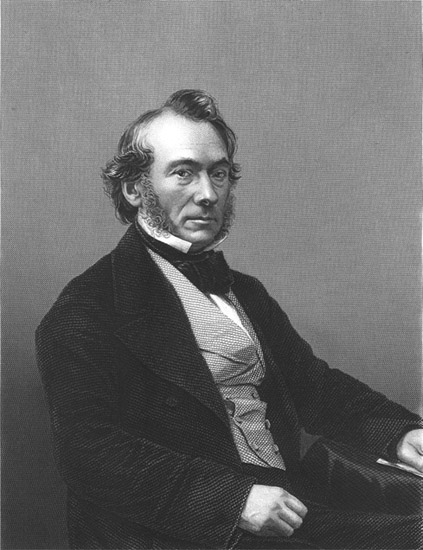

Richard Cobden (1804–1865), an industrialist from Manchester, England, fought to abolish the “corn laws” prohibiting grain imports. The struggle over the laws pitted manufacturers—who wanted cheaper sources of food for their workers—against agricultural interests. (© Topham/The Image Works)

These laws adapted to market conditions, both domestic and foreign. For example, between 1660 and 1814 duties and tariffs on grain imports and exports were on a de facto “sliding scale”; that is, they were adjusted to changes in market conditions, so as to attain the aims of both maintaining domestic supply and sustaining profits from grain sales for landowners. In 1773, 1791, and again in 1804, the laws were amended; in the first instance, to reduce duties, and in the latter instances, to compensate landowners by raising grain prices.

Under the provisions of the Corn Law of 1815, imports of wheat were prohibited until the price of domestically produced grain rose to a preset level; this effectively ended the de facto sliding scale system of import duties that was reimposed, a decade later, in 1828, and revised again in 1842.

Although initially supported by Thomas Robert Malthus, and opposed by David Ricardo on economic grounds, the Corn Laws eventually became both a political and an economic issue. Much has been written on the respective stances taken by Malthus as against Ricardo regarding the Corn Laws. What is important to remember, however, is that Ricardo did not advocate the immediate repeal of them; rather, he wanted their gradual abolishment, so as not to harm the agricultural sector in Britain.

Between 1836 and 1839, an anti–Corn Law movement developed, led by John Bright and Richard Cobden. This movement gained political support from British merchants, bankers, traders, manufacturers, industrialists, and political radicals alike. The merchants and industrialists attacked the laws as subsidizing agriculture at the expense of industry, trade, and economic growth. The political radicals attacked them as benefiting landowners at the consumers’ expense, since the imposition of the laws was, in their view, an implicit tax on food.

In 1845, two events occurred that finally catalyzed mass opposition to the Corn Laws. The Irish potato crop failed, and famine resulted. In addition, heavy rains in Britain that year ruined crops and created food shortages. Under increasing nationwide public pressure, Robert Peel’s Tory government finally repealed the Corn Laws in 1846. The repeal of the Corn Laws, therefore, not only represented the triumph of Ricardo, Adam Smith, and free trade, it also represented the newly acquired political clout of a newly crystallized middle class in Britain, especially after the Reform Act of 1832.

Warren Young

See also: Agriculture; Great Britain; Malthus, Thomas Robert.

Bibliography

Kadish, Alon. The Corn Laws: The Formation of Popular Economics in Britain. Brookfield, VT: Pickering and Chatto, 1996.