A series of Christian campaigns from Europe to the Holy Land lasting from 1096 to around 1270, also known as Holy Wars.

The Crusades were the largest military undertaking up to the time, involving an estimated 150,000 to 600,000 crusaders distinguished by the bright red crosses displayed on their garments, flags, and armor. The Crusades were the climax of the Middle Ages when feudalism, with its values of landownership and military strength, dominated Europe. The Crusades also demonstrated the dominance of the Roman Catholic Church, a wealthy and powerful institution during this time when Europeans saw God’s will in every event. The church was a great landholder, and the pope was the most influential leader throughout Europe. The Crusades began as a way for the church to achieve both spiritual and practical objectives.

The church sought to reduce feudal land wars between European lords. In 1054, the Great Schism between the Eastern (Byzantine) Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches had divided Eastern and Western Christianity. In 1071, the Muslim Seljuk Turks had captured Jerusalem from the Egyptians and had also captured most of Asia Minor from the Eastern Christian empire of Byzantium. The Byzantine emperor appealed to the pope for military aid. The pope had a vision of a renewed Holy Roman empire reuniting East and West with the Roman Catholic Church at its head. The Holy Land was also spiritually important because of the number of Western Christians who took pilgrimages to shrines in the area for religious benefit. Many viewed the crusaders as armed pilgrims. The Crusades also followed the social ideals of faith, pride, honor, and chivalry. The Crusades clearly fit within the preexisting political, religious, economic, and social framework of eleventh-century Europe.

Pope Urban II called for crusaders in a dramatic speech at the Council of Clermont, which gained the support of French nobles and serfs chanting, “God wills it.” He also used letters, emissaries, and other councils to spread his message, although not everyone responded favorably or rushed to join. Most Western Christians never became crusaders. The crusading armies were to rendezvous in Constantinople after departing from different places in Europe in August 1096. People joined the Crusades for a variety of reasons. The church promised to protect the crusaders’ fiefs and personal goods, free crusading serfs, excuse crusading villagers from taxes, absolve crusaders of their debtors, and free any criminals who joined. Younger sons of noblemen hoped to gain land, and all crusaders sought the church’s promise of salvation. Many crusaders also shared the common belief that Islam was a violent, intolerant religion. Idealism, adventurism, conquest, and the desire for personal gain were all strong motivations. These characteristics of the Crusades meant that they were often not coherent or cohesive movements. The French dominated the First Crusade, which consisted of two separate movements, the Paupers’ Crusade and the Barons’ Crusade.

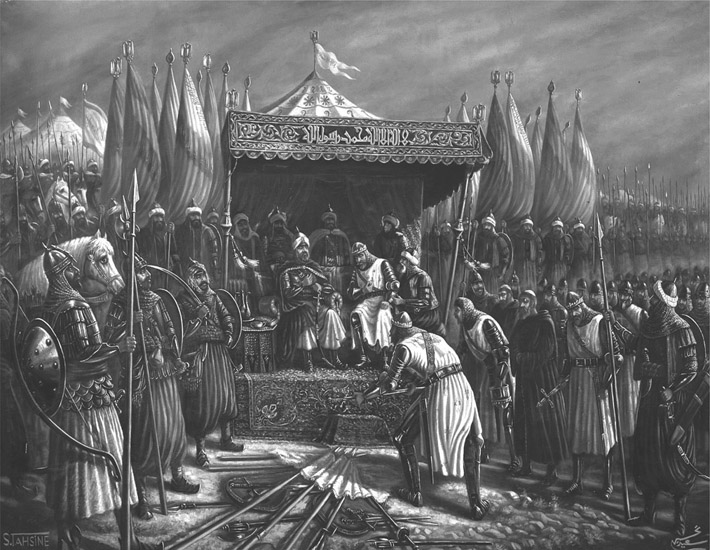

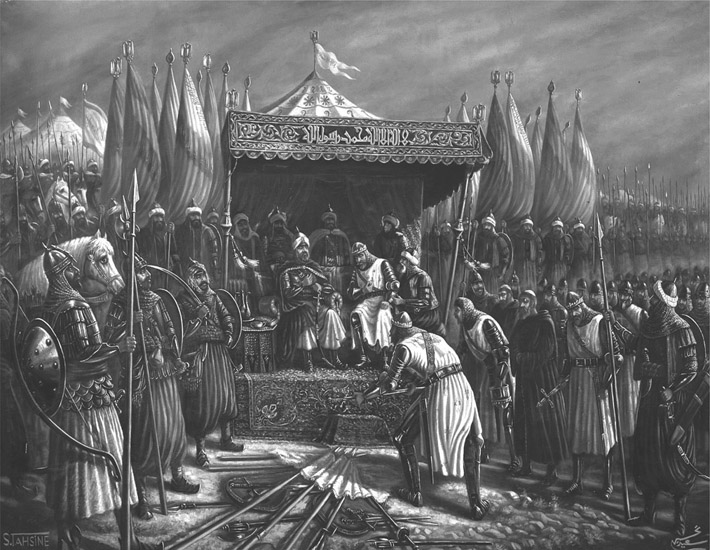

Shown here is English king and crusader Richard I’s surrender to Muslim military head Saladin after the Battle of Hattin (in modern-day Israel) in 1187. The Crusades—the centuries-long effort by European Christians to conquer the Holy Land from the Muslims—introduced many Europeans to new spices and other commodities from the East, helping to spur Eurasian trade. (The Art Archive/National Museum Damascus Syria/Dagli Orti)

First Crusade

The Paupers’ Crusade, the largest and least effective, consisted of peasants seeking relief from famine, disease, and poverty at a time of agricultural depression. In 1094, one year before the pope issued his call for the Crusades, a preacher named Peter the Hermit gathered over 40,000 French and German crusaders, most of which were untrained and unarmed. He persuaded the poor to join him in freeing Jerusalem from the infidels (Muslims) and claimed he had a document written by Jesus demanding that Europeans do so. It was disorganized, often violent, and ended with most of them being killed by the Muslims before reaching Jerusalem. The Barons’ Crusade was more organized by the nobility of Europe and was successful.

The Barons’ Crusade consisted of about 20,000 knights plus servants, archers, and foot soldiers with assorted weapons. These knights were divided into four armies who planned to merge in Constantinople. Leaders included Count Raymond of Toulouse, Godfrey of Bouillon, his younger brother Baldwin, and the Norman Lord Bohemund of Taranto. These knights joined the First Crusade at enormous personal cost and risk. Byzantine emperor Alexius worried about the barons’ motivation and demanded that they swear allegiance to him as head of all conquered lands.

Their first target was Nicaea, which they successfully seized in May 1097 while most of the Turkish troops were away defending Armenia. The crusaders then fought the Turks in a bloody battle at the city of Dorylaeum in central Turkey. The crusaders were slower but more heavily armored and were able to defeat the great Turkish ruler in Asia Minor and gain his riches. A myth of their invincibility quickly spread, and the crusaders found little resistance and many Christian supporters in other Turkish cities. The crusaders suffered, however, because of the hot, arid conditions and the water wells poisoned by the retreating Turks. Many crusaders died or turned back as rivalries for land and quarrels over strategy divided their leaders.

In October 1097, the crusaders laid siege to Antioch, a vast, heavily fortified city, but again encountered problems. The besieged Turks were able to get food and supplies through the surrounding mountains, while the crusaders suffered from starvation, disease, and harsh winter weather. Their strength was reduced when the Byzantines returned to Constantinople. When spring arrived, they were encouraged by the arrival of Italian supply ships. Antioch was taken by the crusaders on June 3 and the Turkish army from Mosul attacked on June 28. Antioch should have been able to defend itself, but a former Christian guard opened the gates of the city for the crusaders. At this time, peasant soldier Peter Bartholomew dreamed of the location of the Holy Lance that had pierced Jesus’ side: under the Church of Saint Peter in Antioch. The discovery of a rusty spear was seen as a sign of God’s forgiveness and victory if they repented their wickedness. The barons then went on the offensive and forced the Turks to retreat.

Count Raymond led the crusaders from Antioch to Jerusalem, capturing a number of towns and cities along the way. In June 1099, the crusaders reached Jerusalem. The city was heavily fortified, and its residents had gathered stores, poisoned wells, and expelled Christians in preparation for the crusaders’ arrival. The crusaders attacked but were repelled, so they were forced to lay siege in the hot, dry conditions. Their low morale was again lifted by the arrival of Italian supply ships and by the priest Peter Desiderius, who had a vision promising victory if they sacrificed their personal ambitions. In mass hysteria, the crusaders attacked and broke through the city’s defenses and slaughtered all the Muslims and Jews who occupied the city. The First Crusade was successful after three years, and its veterans were viewed as heroes who had served their leaders and would now gain their rewards. Those who deserted were villianized. The victors began to establish crusader states, that is, small outposts that were run like feudal kingdoms.

The barons who led the crusaders chose Godfrey of Bouillon as king of Jerusalem, or defender of the Holy Sepulcher. Each baron swore a loyalty oath. Some barons returned home, while others claimed other cities or regions. Godfrey and his successors stressed diplomatic relations, making peace with Egypt and with neighboring barons and establishing trade with Italian cities. They expanded their holdings and established forts that controlled traffic on trade routes and exacted tolls. The barons maintained control in part because of the new Orders of Knights, which were created as a direct result of the First Crusade: the Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem (the Hospitalers) and the Knights of the Temple of Solomon (the Templars). The Latin kingdoms were constantly plagued by land wars among the crusading barons and by their lack of the peasant labor needed to recreate the feudal system. They lost their military advantages as the Muslims began to reunite under the Sultan Zengi and exploited the fact that the crusaders were unable to fight in hot armor for long periods of time. Baldwin III began urging the pope to call a new crusade.

Second Crusade

Pope Eugenius III and King Louis VII of France called for the Second Crusade. Bernard of Clairvaux became a powerful recruiter and the Second Crusade’s leader. Bernard recruited the German emperor Conrad and many German nobles. Conrad divided his army while marching from Constantinople to Nicaea and the Turks were able to surprise and rout the crusaders. When Conrad fell ill and returned to Constantinople, Louis could not control the army. The crusaders once again faced starvation, raiders, and desertion. In 1148, Louis, Conrad, Baldwin III (the boy king of Jerusalem), and his regent mother decided to attack Damascus, the last attempt the Latin kingdom would make to capture this area. They were initially successful, but conditions soon forced them to return to Jerusalem in defeat, marking the end of the Second Crusade. The Second Crusade’s failure weakened the Roman Catholic Church’s influence and lessened the Crusades’ appeal.

Western Christians were less supportive, and Baldwin struggled to keep the remaining areas of the Latin kingdom intact. Baldwin successfully conquered Ashkelon, which was the last great Christian victory in the Holy Land. Baldwin died after establishing an uneasy truce with the Muslim ruler Nurredin and his son and successor Saladin, who began unifying the Muslim world in 1183. Reynald, the untrustworthy ruler of Antioch, broke the truce later that year, leading to the Battle of Krak des Chevaliers, where Saladin was driven back and agreed to a new truce. In 1187, Reynald once again broke the truce and Saladin began a jihad (holy war) to recover Jerusalem from the Christians. The barons marched from Jerusalem but suffered from heat and thirst in the hills of Galilee as Saladin’s army surrounded them. Most of the barons’ army was destroyed in the Battle of Hattin and Jerusalem fell after a short siege. These defeats effectively ended Christian rule in the Middle East.

Third Crusade

The church stated that the Christians’ sins had cost Jerusalem and Pope Clement III promised to dissolve the debts of fighters who joined the Third Crusade. King Philip Augustus of France, King Henry II of England, and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa of Germany led the crusade and forced nonfighters to pay a tithe. Frederick set out alone and entered the Holy Land but drowned crossing a river. Most of his followers returned home or were captured by the Turks. Henry and Philip took over leadership. In 1191, they laid siege to Acre and were later joined by Richard the Lion Heart, who succeeded Henry to the English throne. Philip left after the siege but Richard remained, recapturing a few towns as well as several castles and a large Muslim caravan. Jerusalem was too fortified to attack, but Richard negotiated Christian access to the city, as well as to Bethlehem and Nazareth. Richard was famed for his valor, and he and the great Muslim leader Saladin admired each other. Richard later negotiated a peace treaty ending the Third Crusade when he learned of trouble at home. The crusade was not just a military and political failure, it also began fostering religious doubts about the crusading ideal.

Fourth Crusade

Growing disillusionment and criticism marked the last series of smaller crusades. The Fourth Crusade, organized by Pope Innocent III and led by French lords, was hampered by a European political climate dominated by the intermittent war between England and France. Innocent III hoped to stabilize the conflict by means of uniting once again against the infidel, or nonbeliever of Christianity, but he had minimal influence over the crusade in the increasingly secular age.

The crusaders sought to regain Jerusalem, but they also agreed to attack several smaller ports and trade cities along the route to please their financial backers from Venice, Italy. The practical need for transportation, rather than the pope’s influence, led to the alliance with the Venetians. The crusaders further angered the pope by aiming for Constantinople rather than for Jerusalem after promising the emperor Alexius aid in his struggle to control the city. In exchange, Alexius promised the crusaders money, submission of the Greek Orthodox Church to Rome, and an army of 10,000 to accompany them to Jerusalem. The crusaders were expelled, however, when the citizens of Constantinople discovered Alexius’s promises. The crusaders returned to sack the city and the Byzantine empire crumbled. These events drove a wedge between the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches, resulting in lasting hatred and mistrust.

Remaining Crusades

The Fifth Crusade, led by Duke Leopold of Austria and King Andrew of Hungary, achieved little as the Christians and the Muslims were at peace. The Sixth Crusade, led by Emperor Frederick II of Germany, was unauthorized by the pope and led to the emperor’s excommunication. Frederick had married the daughter of the king of Jerusalem and in 1229 he befriended the Muslims, who gave him control of Jerusalem, Nazareth, and Bethlehem. Other scattered efforts included the tragic 1212 Children’s Crusade in which many children died or were captured and forced into slavery. The last crusade, led by King Louis IX of France for purely religious motives, was sparked by the Islamic Turks’ (Mamelukes) 1244 conquest of Jerusalem. Louis was unsuccessful but was later canonized by the pope. His failure to recapture Jerusalem marked the end of the Crusades. On the whole, well-meaning but flawed leaders led to the Crusades’ ultimate failure after hundreds of thousands had lost their lives and fortunes.

Effects of the Crusades

Scholars still debate the Crusades’ merits and importance, but cannot deny that they had many effects on both the Eastern and Western worlds. They built Western commerce by opening Eastern trade and brought sugars, spices, silks, silverware, dishes, glass windows, and other luxuries to Europe. They created a new European middle class of merchants, craftsmen, and clerks and increased currency’s importance. Some scholars argue that they helped foster the Renaissance. At the same time, the Crusades hurt the Byzantine empire they had been originally organized to help. The Crusades increased the persecution of Jews as well as Muslims and led to other campaigns against opposing religious groups. They also contributed to the development of more intolerant attitudes among many Muslims shocked by the Crusades’ atrocities. The Crusades lessened feudal wars by opening new lands for conquest as they hastened feudalism’s demise when kings and nations gained power. Finally, the Crusades improved military technology and fostered a spirit of exploration, conquest, and colonization that would continue into the following centuries.

David Treviño

See also: Byzantine Empire; Christianity; Exploration and Trade; Islam.

Bibliography

Armento, Beverly J., et al. Across the Centuries. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 2003.

Armstrong, Karen. Holy War: The Crusades and Their Impact on Today’s World. New York: Random House, 2001.

Bartlett, W.B. God Wills It!: An Illustrated History of the Crusades. Stroud: Sutton, 1999.

Biel, Timothy Levi. The Crusades. San Diego: Lucent, 1995.

Phillips, Jonathan, and Martin Hoch, eds. The Second Crusade: Scope and Consequences. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001.

Prawer, Joshua. The World of the Crusaders. New York: Quadrangle, 1972.

Queller, Donald E., and Thomas F. Madden. The Fourth Crusade: The Conquest of Constantinople. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997.

Richard, Jean. The Crusades, c. 1071–c. 1291, trans. Jean Birrell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The Crusades: A Short History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

Tyerman, Christopher. The Invention of the Crusades. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998.