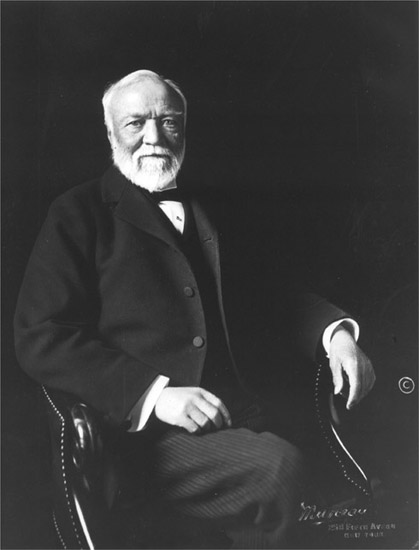

An industrial magnate, as well as a prolific and influential writer, who rose from poverty.

Andrew Carnegie’s writings celebrated individualism, competition, economic growth, and democracy and challenged the wealthy to practice a philanthropy that would elevate humankind.

When Carnegie immigrated to the United States from Scotland at age thirteen, poverty compelled him to work as a bobbin boy in a cotton factory. Making opportunities for himself, working hard, and learning fast, he rose to become superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s western division by age twenty-four. Desiring greater autonomy, Carnegie left the railroad in 1865 to run his own enterprises. By the end of his career, the vertically integrated Carnegie Steel Company had become the world’s largest steel producer. In 1901, he sold his interests to J.P. Morgan’s syndicate for $300 million, making him one of the world’s richest men. Thereafter, he turned his attention to distributing his wealth and promoting international peace.

As much as he wanted to make money and outdo business rivals, Carnegie had a desire to influence public opinion by publishing many magazine articles and books. Carnegie’s general thesis was that America’s democratic institutions and the economic and social freedoms they encouraged were responsible for its ascendance over monarchical Europe. His message and style are exemplified in Triumphant Democracy. It opens, “The old nations of the earth creep on at a snail’s pace; the Republic thunders past with the rush of the express.” Carnegie stood for a meritocracy in which, with integrity, thrift, self-reliance, optimism, and hard work, any man and his family could ascend the economic ladder.

Andrew Carnegie rose from poverty to become an industrial magnate, as well as an influential writer. His writings celebrated individualism, competition, economic growth, and democracy and challenged the wealthy to practice a philanthropy that would elevate humanity. (Library of Congress)

Until his later years, he defended the era’s relatively laissez-faire economic policies and championed the law of competition, “for it is to this law that we owe our wonderful material development, which brings improved conditions in its train.” Carnegie argued that the high tariffs of the late 1800s had little impact on most American manufacturing industries because foreign producers could not have competed successfully in their absence and because American firms competed so vigorously with each other. Indeed, economic historians agree that America’s comparative advantage in the late 1800s was in goods, like steel, which relied on nonrenewable natural resources. Carnegie saw free trade as a goal not “within the reach of practical politics in the lives of those now living,” because there was no alternative revenue source for the federal government. However, free trade remained a distant goal:

Far be it from me to retard the march of the world toward the free and unrestricted interchange of commodities. When the Democracy obtains sway through-out the earth the nations will become friends and brothers, instead of being as now the prey of the monarchical and aristocratic ruling classes, and always warring with each other; standing armies and war ships will be of the past, and men will then begin to destroy custom-houses as relics of a barbarous and monarchical age, not altogether from the low plane of economic gain or loss, but strongly impelled thereto from the higher standpoint of the brotherhood of man.

While vast income inequalities were “inevitable,” Carnegie did not glorify greed and opulence. Instead, he argued in The Gospel of Wealth that “the man who dies rich dies disgraced” because the wealthy man should “consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer.” The man who created it, because he has superior wisdom, experience, and ability to administer, should distribute excess wealth. With these talents, he could do more to elevate the people, than they or the state could ever do. Carnegie emphasized that wealth should not be given to “charity,” but that it go to libraries, schools, museums, and other projects that help those who would help themselves.

Robert Whaples

See also: Steel.

Bibliography

Carnegie, Andrew. Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1920.

———. The Gospel of Wealth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962.

———. Triumphant Democracy or Fifty Years’ March of the Republic. New York: Scribner’s, 1886.

Livesay, Harold. Andrew Carnegie and the Rise of Big Business. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1975.