A strait, whose name came from Dardanus, an ancient Greek city on its Asian shore, called Hellespont in antiquity and Çanakkale Bogazi in Turkish.

The Dardanelles is thirty-eight miles long and from one to four miles wide. Together with the strait of Bosporus, the Dardanelles connects the Black Sea with the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas. It separates the Balkan Peninsula in Europe from Anatolia in Asia, and had an essential role for defending the cities situated nearby, for example, ancient Troy and then Constantinople (Istanbul).

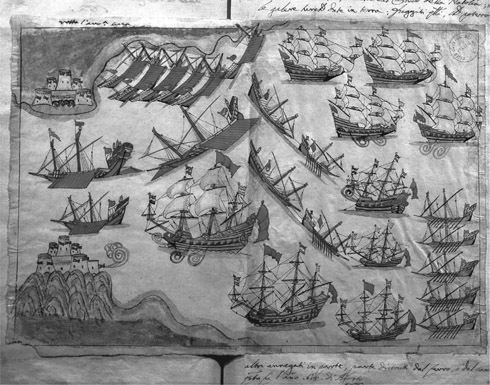

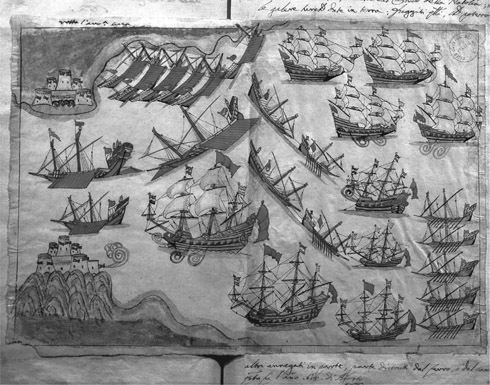

The Dardanelles, the strait connecting the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, has been a major trading route since ancient times. This strategic body of water has been fought over many times, including this seventeenth-century battle between the Ottoman and Venetian fleets. (The Art Archive/Museo Correr Venice/Dagli Orti)

In modern times, the straits of Dardanelles and Bosporus belong to Turkey, but because of their colossal strategic and commercial importance for the navigation between the Mediterranean and Black Seas, a number of empires have fought for control of them throughout the centuries.

The Dardanelles Under the Ottomans

The Dardanelles were under the Byzantine empire’s control up to the thirteenth century, when a Turkish tribe settled and founded the small principality of Karesi on the Asian shore of this strait. In 1334 and 1345, the Ottomans gradually annexed this emirate and implicitly the Anatolian shore of the Dardanelles. The European shore still remained under Byzantine control, and for this reason the Ottoman troops could not cross safely from Anatolia into southeastern Europe. The Christians could obstruct any attempt by the Turks to establish and hold settlements in Thrace on the European shore of the strait of Dardanelles. That is why Orhan, the second Ottoman sultan, aimed to take under his authority the strait of Dardanelles. In this respect, in 1352, Süleyman, Orhan’s first son, captured the fortress of Tzympe and began laying siege to the strongest fortress in the area: Gallipoli. In March 1354, following a strong earthquake, the Ottoman troops occupied Gallipoli and several other small fortresses. The Ottomans maintained Gallipoli as a naval base because of its strategic importance for the defense of Istanbul and a key transit station between the military and trading traffic between Asia Minor and the Balkan Peninsula.

The strait of Dardanelles came under complete Ottoman control after Mehmed II built fortresses at Çanakkale (a settlement situated at the mouth of Kodja River [the ancient Rhodius River]) on both shores of the Dardanelles in 1462 and 1463, and fortified Tenedos Island (Bozcaada), which was situated at the entrance to the Dardanelles. In this way, he secured the military and trading communications between Anatolia and Rumelia, especially against attacks by Venetian ships. From that moment, the Ottomans started to exclude gradually the Italian merchants—Genoese and Venetian, especially—from the Black Sea trade.

The Aegean regions and especially Istanbul, the new capital, needed the foodstuff from the northern Black Sea. In this respect, Mehmed II limited and then forbade the export of wheat, fish, oil, salt, and other foodstuff to Italy. First, Ottoman officials checked the Italian ships coming from the Black Sea at Istanbul, on the strait of Bosporus. Other officials closely inspected the same ships a second time at Gallipoli, on the strait of Dardanelles. Actually, in the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, the Dardanelles became a traditional checking point for west European trading ships navigating to and from Istanbul. Also, the Dardanelles was the place where Ottoman warships started to accompany the commercial convoys of ships, which sailed out of Istanbul, to protect them against corsairs during their travels across the Aegean and then the Mediterranean Seas.

On the other hand, the blockade of the Dardanelles by Christian ships during the wars with the Ottomans created a real danger for those merchants seeking to trade with Istanbul. In 1650, the Venetian fleet, failing to achieve an understanding with the Turkish sultan, blockaded the Dardanelles. The French assisted the Venetians in the early 1700s. That is why the fortifying of the Dardanelles did not end in the fifteenth century but continued into the next several centuries. Two hundred years later, from 1659 through 1661, the grand-vizier Mehmed Köprülü built two other solid fortresses, Kum Kale and Sedd ül-Bahr, on either side of the strait.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the status of the straits of Bosporus and Dardanelles was a major diplomatic controversy between the Ottoman empire, the Western powers, and Russia. After military conflicts or diplomatic pressure, the Ottomans accepted to open the straits of Dardanelles and Bosporus to merchant ships, but not to warships. Warring against the Ottomans from 1768 to 1774 and from 1787 to 1792, Tsarina Catherine II of Russia gained the northern coast of the Black Sea and the right of Russian ships to sail from the Black Sea into the Mediterranean Sea by way of the Ottoman-controlled Dardanelles.

The Russian expansion along the Black Sea and the resulting weakening of the Ottoman empire became of great concern to the Western powers, notably England and France. That is why the Ottomans tried to impose, on international diplomacy, the principle that no warships of any power should enter the straits of Dardanelles and Bosporus. The Treaty of Dardanelles, signed between the Ottoman empire and Great Britain on January 5, 1809, affirmed and emphasized for the first time this principle. Later, even Russia wanted to protect its possession in the Black Sea region, so it imposed, by the Treaty of Hünkar Iskelesi of July 8, 1833, the permanent closure of the straits of Dardanelles and Bosporus to warships.

But the straits remained opened to merchant ships. And this was stipulated as a most-favored-nation clause in almost all peace and commerce treaties between the Ottoman empire and the Western powers. For instance, the Treaty of Commerce and Navigation between the United States and the Ottoman empire, signed at Constantinople on May 7, 1830, stipulated in Article 7 that U.S. merchant ships had liberty to pass the straits and go and come in the Black Sea. Also, according to Article 5 in the Convention of Commerce and Navigation between Her Britannic Majesty and the Sultan of the Ottoman empire, signed near Constantinople on August 16, 1838, which became a diplomatic pattern for the capitulatory regime of international trade in the Ottoman empire, the British merchant ships could pass freely through the straits of Dardanelles and Bosporus.

The Russians continued to dream about controlling Istanbul and the straits, so as to control the water trade route connecting the Black and Mediterranean Seas. England and France joined forces to prevent Russia from gaining control over, or special rights in, the Straits and opposed these Russian ambitions as threatening their trade routes. In 1841, England, France, Russia, Austria, and Prussia signed the London Straits Convention, agreeing to close the straits to all but Turkish warships in peacetime and reaffirming the principle of the 1809 convention that no warships of any power should enter the straits of Dardanelles and Bosporus. Russia began hostilities when the Ottomans refused to grant to it the right to protect Orthodox Christians. In the so-called Crimean War (1853–1856), the Ottoman, French, and English armies defeated Russia. The peace treaty of the Congress of Paris of March 30, 1856, formally reaffirmed the closure of the straits to all but Turkish warships in peacetime, as stipulated in the convention of 1841, and confirmed generally the free access of all commercial flotillas through the straits and in the Black Sea. It was a stipulation, which remained in force until World War I, theoretically at least.

The Dardanelles Since World War I

The Gallipoli Campaign of and the battle for the Dardanelles (1915–1916) during World War I proved once again the importance of controlling the straits both for Turkey and for the European powers. The Turkish army succeeded, losing around 120,000 soldiers in the process, in resisting the French and English offensive and consequently in protecting Istanbul and avoiding the conclusion of an unfavorable peace. In the Agreement of Mudros on October 30, 1918, following Turkey’s capitulation from the war as an ally of Germany, the allies imposed the maintenance of west European troops in the straits area and permitted free traffic through the straits of Dardanelles and Bosporus. The Treaty of Sèvres, which was concluded by the victorious allied powers with Turkey on the August 10, 1920, internationalized and demilitarized the straits zone, and was eventually superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne (1923). The zone was restored to Turkey, but was to remain demilitarized; the straits were to be open to all ships in peacetime and in time of war if Turkey remained neutral; if Turkey was at war, it could not exclude neutral ships. Secretly, however, Turkey soon began to refortify the zone, and in 1936, by the Montreux Convention, it was formally permitted to remilitarize it. Turkey has maintained the right to restrict the access of ships from non–Black Sea states.

Even after World War II, the Dardanelles remained a diplomatic target. In 1947, Turkey was under pressure from Russia for concessions over the Dardanelles. The Turkish government, bolstered by American economic and military aid, has withstood Russian demands for control of the Dardanelles.

Viorel Panaite

See also: Black Sea; Genoa; Grain; Mediterranean Sea; Oil; Ottomans; Salt; Venice.

Bibliography

Dontas, Domna N. Greece and Turkey: The Regime of the Straits, Lemnos and Samothrace. Athens: G.C. Eleftheroudakis, 1987.

Hershlag, Z.Y. Introduction to the Modern Economic History of the Middle East. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1980.

Macfie, A.L. The Straits Question: 1908–36. Thessaloníki: Institute for Balkan Studies, 1993.

Puryear, Vernon John. England, Russia and the Straits Question, 1844–1856. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1931.

Shotwell, James Thomson, and Francis Deák. Turkey at the Straits: A Short History. New York: Macmillan, 1940.

Vaughan, Dorothy M. Europe and the Turk: A Pattern of Alliances, 1350–1700. Liverpool: University Press, 1954.