The process of constructing systems of political influence.

The empire-building process permits certain polities to exercise a high and continuous degree of control over others existing outside their nominal geographical boundaries—sometimes, although far from invariably, as a prelude to full incorporation of the controlled polities into the controlling one, and often, but not invariably, through the medium of the colony. The word “empire” itself derives from “imperium,” a central political concept of the Roman empire that has had many meanings in political discourse from Roman to modern times, often denoting simply the authority exercised by a sovereign and sometimes referring to the rule of a superior monarch to whom other monarchs were subject. The modern usage inherent in the term “empire building” has been closely connected to the idea of “imperialism.” Both developed as concepts during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and both came to be fixed in political vocabulary during the last third of the nineteenth century. The type of historical phenomenon to which they refer is, however, very old indeed, dating back at least to the formation of the earliest extensive states in the Middle East in the third millennium B.C.E.

Ancient Empires

Trade has almost always been implicated, sometimes very intimately, in projects of empire building. It has been theorized that the first significant empires in the ancient Middle East were constructed at least in part to control and derive income from trade connecting Mesopotamia and other areas. Most of the empires of the ancient world, regardless of whether or not they were constructed primarily for reasons relating to trade, necessarily incorporated trading systems within themselves, if only because the conduct, or at least the taxing, of trade offered a source of revenue. In almost all cases of ancient empires of which we have detailed knowledge, however, commercial factors were linked in one form or another to a great many others, so that it is often difficult to disentangle trade from politics, warfare, agriculture, public finance, and forms of economic exploitation that we would hesitate today to call “commerce.” Most of the acts through which the Roman empire was constructed are reported by their ancient historians to have had little to do with trade and more with countering military threats, defending the honor of Rome, advancing the ambitions of politicians, and so forth.

And yet we discover that there was almost always a set of commercial relationships, usually of quite long standing, between the areas Rome controlled and the regions it decided to conquer, that conquering (and occasionally, as in Germany in the first century C.E., retreating) Roman armies were accompanied by merchants and traders who supplied the troops, purchased booty and slaves, and were clearly able to exploit preexisting relationships with local economies. By extending its control over the Mediterranean and the lands on all sides of it and by maintaining a naval force that reduced piracy to manageable proportions, Rome promoted an expansion of commerce larger than the region had ever seen before. And although the early Romans did not portray themselves as being a particularly commercial people, as Roman citizenship became available to persons from places throughout the empire, its advantages for merchants trading within and beyond the empire were so clear that large numbers of businessmen actively sought to acquire it. Some of the central commercial activities of the Roman empire at its height were, however, not entirely consistent with our standard notions of trade. For instance, the grain trade between Egypt and Rome was more like a state activity, a system of appropriating the bulk of the grain produced in Egypt, transporting it to Italy, and distributing it in Rome. On the other hand, around the grain system a substantial amount of market-based commercial activity of a more ordinary sort took place, headquartered in the immensely busy trading city of Alexandria in Egypt. We shall see that this kind of situation existed in some of the European empires of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as well.

The role of trade in the construction and operation of other great territorial empires of premodern times varied considerably, although in many cases the variation may have been due more to the ways in which commerce was valued in the prevailing moral order than to the realities of its practical role in the life of society and the state.

In China, for example, according to the Confucian worldview adopted as the conceptual framework of the imperial bureaucracy, trade was a suspect activity, sometimes useful but always dangerous to public morality because of the selfishness that lay at its motivational core. Theoretically, the place of merchants in the order of society was well below that of peasants. In reality, China was for the whole of the Common Era one of the great trading centers of the world, the key marketing area and producer of manufactured goods for all of East Asia. Chinese silks were the mainstay of trade across Central Asia and a crucial factor in China’s diplomacy beyond its boundaries. Yet, except for relatively brief periods, the Chinese government declined to acknowledge the full significance of commerce, whether domestic trade between regions of China or external trade. As late as the eighteenth century, when China’s public and private finances had come to be dependent on the silver imports that arose from the export of Chinese goods through Western merchants, Chinese authorities still pretended that foreign trade did not matter, that China required nothing from the outside world, and that imports into China from abroad were merely tribute paid by lesser monarchs to the emperor.

Another example is afforded by the succession of large territorial empires from the tenth century to the end of the sixteenth century in the western Sudan, just south of the Sahara in the interior of West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. The economic basis of these empires appears on good evidence to have the trans-Saharan gold trade, the enterprise through which North Africa, Europe, and the Middle East acquired most of the gold that served as the primary medium of finance and exchange in the medieval period. The gold was mined in interior areas of the modern states of Ghana and Guinea, exchanged for salt from the edges of the desert, and transported across the Sahara along well-established routes to the cities of North Africa. The trade itself existed from Roman times until the eighteenth century, regardless of whether or not a single political entity controlled the area south of the desert through which it crossed at any particular time.

In a general sense, the empires that rose and collapsed there were not essential to the trade, although they may in some ways have facilitated it. But it is quite clear that controlling the trade was among the major objectives of the peoples who formed the empires. Nevertheless, the surviving epics and written histories that contain the consciously constructed records of the empires of Mali and Songhay make few references to the gold trade, featuring instead the feats of heroes, the imperatives of religion, and the rivalries between peoples and regions.

Early European Empire Building

The history of empire building as an aspect of modern imperialism begins in the early fifteenth century, and at that time trade was directly at its center. In the 1420s, a Portuguese enterprise led by Prince Henry the Navigator and backed by financial supporters that included Italian mercantile interests began exploring the coasts of western Africa, primarily to make contact with the countries from which the gold that entered the trans-Saharan trade came. It was hoped that some or all of the gold could be diverted onto Portuguese ships, which would benefit the investors, the Portuguese state, and, in a general sense, Christendom in its competition with Islam. By the time Henry died in 1460 and the enterprise fell under the control of the Portuguese government, expeditions had in fact reached areas on the West African coast where gold could be purchased. More of such areas were contacted during the next two decades as the range of Portuguese ships extended all the way to Cameroon. At no time, however, were the Portuguese able to attract more than a relatively small portion of the gold trade into routes under their control. They did, on the other hand, develop some important new forms of commerce in the region—especially the Atlantic slave trade, which Portugal pioneered partly to supply labor to the previously uninhabited Cape Verde Islands, which had been discovered and colonized as a sideline to the main African thrust of the project. Portugal also built some permanent fortifications on the coast (largely against intrusion from other Europeans, not to control African trading partners). This was not much of an “empire,” but what there was of it was based on trade and on the production of commodities such as sugar in the Atlantic islands ruled by Portugal.

Circumstances changed, however, in the 1480s, when Portugal sent expeditions south along the African coast that revealed the Cape of Good Hope and the strong probability that the Atlantic was connected to the Indian Ocean. At that point, the limited resources of the Portuguese state (a very small power by contemporary European standards), backed by funds borrowed outside Portugal, were directed toward bringing Portugal into direct contact around Africa with the flourishing seaborne trade between East and Southeast Asia and the Mediterranean. This trade was conducted through a complex commercial system centered in southwestern India, a fact of which the Portuguese authorities appear to have been aware. A heavily armed fleet under Vasco da Gama was sent in 1497 around the Cape of Good Hope and into the Indian Ocean. The fleet, after contacting the edges of the Indian Ocean system in the towns of the Swahili-speaking peoples of the East African coast, sailed to southwestern India and announced the presence and intentions of Portugal. The Portuguese were not well received, both because they were Christians in a commercial world dominated by Muslims and because they were interlopers clearly attempting to cut out the middlemen in an existing trade. Da Gama noticed, however, that his ships held a technical edge in fighting power.

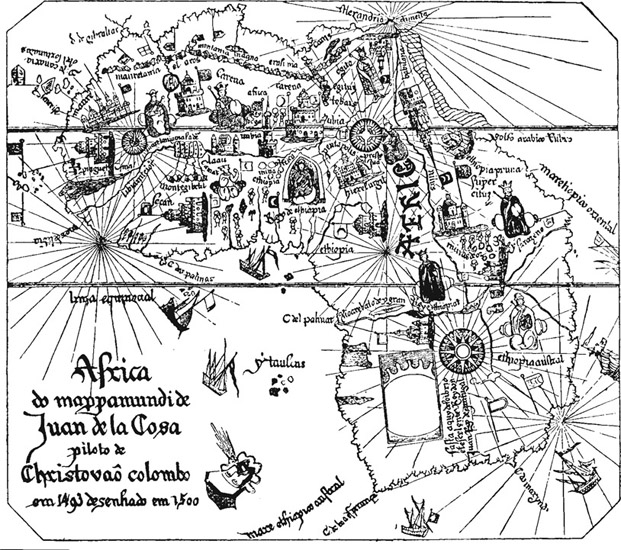

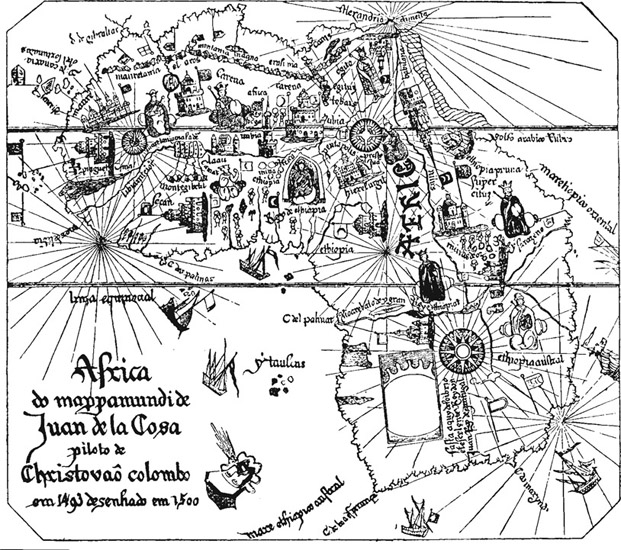

The first European imperial holdings overseas were spearheaded by the Portuguese, as illustrated by this 1500 map of Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama’s voyages. (© North Wind Picture Archives)

In leading Portuguese fleets to India over the next few years, da Gama and his successors learned to use that edge to establish themselves by force at the center of the trading system. They stationed warships off the Indian coast, requiring coastal cities to trade with them regardless of whether they wanted to do so or not. They forced non-Portuguese merchant ships to purchase licenses to allow them to pass unmolested through the area of Portuguese maritime control. In 1510, they captured the readily defensible town of Goa on the southwest coast of India, from which they sent out military expeditions that occupied strategic positions at several constricted points along the traditional Indian Ocean trade routes. By the 1520s, they had successfully withstood naval challenges and had established a limited maritime empire built around trade—one that depended for its existence on mobility, naval strength, and heavy cannon, and therefore on the selective application of extortion and terror.

In subsequent years, the Portuguese carved out for themselves a more positive role in Asia, conducting trade between countries that did not maintain friendly relations with each other (such as China and Japan), offering transportation services between places in Asia, and developing a port of trade with China at Macao that became the primary link between China and the Western world until the end of the seventeenth century. (Portuguese from Macao exchanged Chinese goods for silver from Spanish America at the Spanish colony at Manila, thereby supplying China with what informally became its basic currency.) The Portuguese never managed to divert more than a fraction (perhaps a third) of the European-Asian trade into their ships, but their empire in Asia nevertheless managed to subsist and to become a permanent part of the global economy, despite severe challenges that arose in the seventeenth century. The Portuguese also acquired bases in East and South Africa to protect the way to and from Europe and to provide support for their ships (and to make a profit from the part of the Indian Ocean trade that extended to Africa). In addition, they colonized Brazil, initially as an offshoot of their Asian enterprises.

Although the Portuguese state profited from its Asia–Africa–South American empire in the sixteenth century, the effects of the empire on Portugal itself were relatively small. Beyond certain limits, the tendencies toward developing a significant capitalist economy based on commerce that had been in evidence in Prince Henry’s time did not progress very far, as the enterprise of the Indies became more of an operation of the state than a business undertaking. The income from the empire did not, on the whole, remain in Portugal in the form of capital investments, but was distributed (with the spices and other Asian products) to the commercial centers of northern Europe, especially the Netherlands, from which Portugal obtained the credit that permitted ships to be built and cargoes for the Asian trade to be put together. Portugal did not become a great European power. Rather, Portugal was overshadowed by its larger neighbor Spain, which created its own empire and which, after Portugal failed disastrously in an attempt to conquer Morocco in 1578, took over control of Portugal in 1580 and retained it for more than sixty years.

Spain’s overseas empire became a model for the rest of Europe, in part because it was connected, unlike Portugal’s, with the country that was unquestionably the most powerful in Europe (the Ottoman empire excepted) between the middle of the sixteenth and the middle of the seventeenth centuries. The founding of the Spanish overseas empire began with the voyages of Christopher Columbus in the 1490s and occurred essentially at the same time as (and in many respects as a direct result of) the formation of Spain itself out of the union of Castile and Aragon. The Spanish (actually, the Castilian) state sponsored Columbus to achieve the same aim as Portugal: finding a direct way to trade with Asia. In fact, of course, Columbus found a new continent, although he spent the rest of his life attempting to prove that he had not. Columbus established the first overseas Spanish colony in Santo Domingo in 1493, primarily to serve as a base for further exploration that would reveal the route to the mainland of East Asia and thus as a foundation for expanded intercontinental trade. But like other colonial entrepreneurs for the next two and a half centuries, Columbus attempted to make his colony pay for itself in the short run by exploiting mineral resources (especially silver and gold, if those could be found) and by establishing plantation production of consumer goods (and occasionally raw materials) demanded in Europe. It was the last that (barely) sustained the early Spanish colonies in the Caribbean until the great transformation of the Spanish empire that occurred in the middle of the sixteenth century.

The transformation was a consequence of contact by Spaniards with two major native American states: the Aztec empire of central Mexico in the late 1510s and the Incan empire of Peru in the early 1530s. In both cases, contact was made by small military forces operating under essentially autonomous leaders, not by directly appointed officials of the Spanish state or by traders. In both cases, these leaders decided that instead of trying to establish bilateral commercial and political relations (which held few advantages for them personally), they would use their possession of a more advanced military technology, surprise, and incredible ruthlessness to overcome and rule the indigenous states and to exploit them as directly as possible, and in both cases they got away with it.

In neither case, however, did the conquest in itself change the nature of Spanish imperialism, because the riches initially plundered from the Aztecs and the Incas were not replaced and the economic futures of the new colonies looked uncertain in the 1540s. What effected the change was the discovery by Spanish exploring parties in that decade of two of the richest exploitable silver veins in the world, one in what is today Bolivia and the other in north central Mexico. At this point, the Spanish government intervened heavily in the affairs of its colonies, establishing an extensive (and expensive) system of direct rule in the New World and mustering the resources of the largest financial enterprises in Europe to provide capital for exploiting the newly discovered resources. The Spanish empire in the New World centered on silver, at least according to the official view in Spain and in the imaginations of the rulers of Spain’s European rivals.

According to the official theory of the Spanish colonial empire (a theory that was the model for the legal frameworks of most European overseas empires up to the eighteenth century), the American colonies existed in an economic sense solely to benefit Spain. The key benefit was to be derived from as large and constant a flow of silver as possible from the mines in America into the Spanish state treasury, with as little diversion of the prime commodity as feasible into other pockets. The silver would be used by the Spanish government to pay the expenses of the nation’s great-power standing: the costs of armies and wars, of client states, of bribes to foreign politicians, and of fleets and fortresses to keep other states from attempting to undermine Spanish control in America. In fact, Spain did manage to create and maintain a major source of revenue from the silver “trade,” although not enough to match the needs of foreign policy and war, which led to frequent state bankruptcies even at the height of Spanish power in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

To make the theory work, Spanish law restricted all commercial contacts between its colonies and Europe to ships sailing under official control in carefully regulated fleets with naval escorts. The fleets brought with them all the European (and Asian) commodities that could legally be sold in America, together with the trickle of African slaves that was officially permitted to eke out the labor resources of the colonies. The fleets, on arrival in America, took on their most important return cargoes: the state-owned silver produced in the state-owned mines. They were also supposed to carry all the products of the colonies intended for export to Europe. The intention behind the system was not only to ensure the protection of the silver supply, but also to prevent excessive expansion of the nonsilver economy of Spanish America beyond the minimum necessary to support the mines and maintain the basis of Spanish control. Spanish law theoretically forbade, or at least tried to make very difficult, the construction of an autonomous colonial economy either around internal trade in America or around exports—apart from silver—to the rest of the world.

The official theory, although seriously enforced for over two centuries, did not actually correspond well with reality and therefore could never be fully effective. It illustrates a continuing theme in the history of modern imperialism: the very great divergence that tends to exist between the relatively simplistic ways in which commerce is viewed within the ideological framework of imperialism and the complexities of actual commerce in colonial areas dynamically attached to the global economy. In fact, because Spain required a substantial Spanish population in its colonies to protect its own control and to operate a market economy in support of the silver operations, and also because in many areas it was found desirable to encourage the development of a mixed European–Mesoamerican Indian population of European culture, it could not prevent the appearance of a complex commercial, agricultural, and in some cases industrial economy that functioned parallel to the silver economy.

By the seventeenth century, this parallel economy had come to dwarf the officially recognized one, especially in areas such as central Mexico, where large cities with populations of Western culture had emerged. Intercolonial trade (which was officially forbidden) developed on a large scale, while demand for European and Asian commodities and production for export rose to a scale far beyond the capacities of the treasure fleets to accommodate. Even in the sixteenth century, demand for slave labor for work on American estates far exceeded the officially permitted limits. Between the late sixteenth and the early eighteenth centuries, Spanish America possessed one of the most dynamic economies on Earth—an economy that could be retarded by state policy, but not contained. The result was, among other things, smuggling on a large scale. In the late sixteenth and the first half of the seventeenth centuries, it was smuggling in the Spanish overseas empire and other related activities (such as piracy) that made it possible for the economies of the northwest European states to establish direct, profitable connections with the New World.

British and French Empire Building

Before the early seventeenth century, French and English efforts to establish colonies in the Americas were uniformly unsuccessful. They attracted widespread public interest, and in the case of England they helped to create a kind of nationalist mystique of imperialism as England’s destiny, but the actual results were less than meager. The first hints of success arose from efforts to smuggle slaves into the Spanish colonies in the 1560s and 1570s and from outright piratical raids on Spanish shipping. Even after permanent English and French colonies were established starting in 1607–1608, a significant part of the business that many of them did was involved with the smuggling trade in Spanish America. This was especially true of the formal and informal colonies established by English groups in the Caribbean in the 1620s and 1630s, but the settlements in mainland North America had some of the same character. The latter were, in any case, economically small, almost insignificant, compared to the wealth of the Spanish colonies, until near the end of the seventeenth century. When Englishmen in particular thought about their imperial future in America throughout the seventeenth century, the ideal form of that future was England’s acquisition of most or all of the Spanish empire. When they attempted to rationalize their colonial administration, their first inclination was to imitate Spain.

The first major breakthrough of northwestern Europe into modern commercially based imperialism came not in America, but in Asia. In the late sixteenth century, several expeditions from the Netherlands and England sailed to the Indian Ocean to test the strength of the Portuguese presence. These first efforts were followed in the early seventeenth century by the foundation of the Dutch and the British East India Companies, which were to remain for two centuries the institutional bases for the building of European empires in Asia and the world’s largest trading corporations, inti mately tied to the development of modern capitalism. At the start, it appeared that the two companies would cooperate, but by the 1610s they had become serious rivals, as the Netherlands briefly rose to the status of a great power and as Dutch capital made the Dutch East India Company for the time being the larger and more successful.

The Dutch company pioneered newer, more efficient sea routes from the Atlantic into the Indian Ocean and centered its activities not in India but in Java, in modern-day Indonesia. There, often as a result of decisions taken by authorities on site as opposed to the company’s directors in the Netherlands, they created the core of a substantial land empire, which eventually incorporated large parts of the Indonesian islands and a great deal of Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka). This empire was used as a self-supporting strategic base from which Dutch naval and military forces rapidly built up almost total control of the spice trade and a large part of the Asian pepper trade as well. Control was maintained through large expenditures on armies, fleets, fortifications, and colonial towns, all of which amounted to a heavy overhead that the company bore for the entire period of its existence. In the seventeenth century, the expense seemed to be clearly justified. Not only did the company itself obtain great profits from its direct trade with Europe, but also it supplied Dutch commerce with an array of items that were used to conduct trade throughout Europe and the rest of the world.

The Dutch also pushed aside (although they did not entirely dislodge) the Portuguese from their dominance of intra-Asian seaborne commerce, taking over, for example, the monopoly on trade between Japan and the rest of the world. The Dutch East India Company’s empire was truly built around trade, but its involvement in political control over diverse peoples and political systems, its efforts to control spice production, and most of all, the large overhead that it was required to bear meant that there was always a considerable strain between the aim of conducting commerce profitably and the costs of maintaining the empire. In the eighteenth century, the strain prevented the company from responding effectively to British competition.

The British East India Company had been forced by Dutch successes in Southeast Asia to fall back on the traditional centers of Asian trade in India. More or less by accident, the English company found itself in the third quarter of the seventeenth century in a position to take advantage of a fashion that had suddenly appeared in Europe for Asian textiles, especially colored and printed cottons generically known as “calicoes” that were produced on a large scale in certain areas of India. The English company aggressively marketed calicoes in Europe and exploited the financial and industrial capabilities of India to create an immensely profitable trade, which secured the company’s position in Asian commerce at the same time that it opened the company to intense criticism at home from domestic textile producers. When the latter succeeded (in 1700 and 1720) in getting Parliament to limit and then ban the sale of most types of calicoes in Britain, the company was able to move flexibly to focus on the export of cottons to other countries, and to switch its resources to the exploitation of a new commodity: tea. Although the fashion for tea had also appeared in the third quarter of the seventeenth century, it had taken the East India companies some time before they had become convinced that the custom of tea-taking (like that of coffee drinking) was permanent. In response to a growing demand for tea in the early eighteenth century, the British East India Company sought and obtained permission to conduct regular trade with Canton (Guangzhou) in China. Tea obtained by this means became the mainstay of the company throughout the first half of the eighteenth century and the source of its continuing profitability.

Shown here is the retreat of the British from Concord, Massachusetts, at the outset of the American Revolution. The American Revolution took a large piece out of the British empire and helped to change the nature of the Atlantic economy. (© North Wind Picture Archives)

One of the keys to the British East India Company’s success was that, until well into the eighteenth century, it remained preeminently a trading company. It did acquire direct political control over the immediate vicinity of its main commercial bases in India, especially Madras and Calcutta, the latter by agreement with the Mughal empire and the local rulers of Bengal, but that control was exercised as a convenience for commerce, not as a step toward empire. Except for a brief and unsuccessful episode in the seventeenth century, the company deliberately eschewed the more grandiose policies of its Dutch rival, thereby avoiding the overhead and the political complications that imperialism brought with it. The rewards were obvious: continual profitability, substantial capital accumulation, and the ability to move that capital flexibly into new lines of trade to meet new conditions, as happened with tea. The Dutch company also attempted to exploit the calico fashion and the demand in Europe for tea, but with much less success because it could not concentrate its resources the way the English company could.

However, by the 1740s the English (now British) East India Company found itself moving into a new, more aggressively imperialistic phase, much against the will of most of its directors. The effective collapse of the Mughal empire in the first half of the eighteenth century brought the company’s officials in India into the complex politics of the empire’s competing successor states, both to maintain the company’s position and to take personal advantage of opportunities to make fortunes in the chaos of India’s fragmentation. A serious threat from the French Company of the Indies in the 1740s and 1750s to insert itself into Indian trade and oust the British encouraged the British company to take an enhanced political role in India. During the imperial wars of the mid-eighteenth century (1740–1748 and 1756–1763), the British East India Company’s forces in India, eventually backed by regular British troops and a fleet, led a coalition of Indian allies to defeat the French company and its allies. In the process, the East India company emerged as the paramount power on the Indian subcontinent, while the company’s policies became a central issue of British politics. It was an uncomfortable position for a trading company. The company’s commercial operations were unable to produce an income to meet its expenses in the 1760s and 1770s, while the British imperial presence in India created an opportunity for large fortunes to be made by company employees and interlopers. Through a series of changes enacted in the 1770s and 1780s, mainly in response to company insolvency and a major corruption scandal, Parliament assigned control of the company’s political functions to the British government. Although the East India Company survived until 1858, it became increasingly an arm of government, losing its legal monopoly of India trade in 1813.

While the Dutch and, more spectacularly, the British succeeded in constructing substantial empires in Asia based, initially at least, on seaborne trade, the creation of empires to rival that of Spain in America arose from the establishment of an economic system in which trade was subordinated to colonial production of a consumer commodity: sugar. In the 1650s, the government of Oliver Cromwell attempted seriously to realize the English imperialist aim of conquering the Spanish colonies, starting with the Caribbean. The force sent to do so failed badly, but occupied Jamaica as a consolation prize. The English state, with English investors, moved strongly to retrieve something from the situation. It sponsored a program of promoting the rapid development of Jamaica and Barbados (which England already possessed) as plantation colonies, producing goods for the European market on a large scale. It became clear that the most promising of these commodities was sugar, already in production in Barbados using a technology and slave labor system pioneered by the Portuguese.

With strong government support and substantial investment, the sugar plantations of Barbados and Jamaica expanded greatly in the latter part of the seventeenth century. The demand for sugar also increased throughout Europe, but particularly in Britain, especially after sugar came to be taken customarily with tea, which was the case in Britain by the early eighteenth century. The success of the British sugar plantations led to efforts by France, the Netherlands, and several other countries to establish their own West Indian colonial plantation economies in the late seventeenth and throughout the eighteenth centuries. The French plantations in the country that is today Haiti, in Martinique, and in Guadeloupe became, by the middle of the eighteenth century, even more productive than the British colonies. Much of the imperial warfare of the eighteenth century centered around efforts by the British and French to dislodge each other from their Caribbean colonies, with the honors on the whole going to the British.

Around the colonial sugar economies that developed in the Caribbean, a system of trade, migration, and finance emerged that connected several areas bordering on the Atlantic together. The West African slave trade expanded enormously to meet the demand for labor in the sugar islands. English and French slave traders soon surpassed their Portuguese predecessors in the scope of their operations. The English colonies in North America, which had led a precarious economic existence up to the 1660s, now largely re-oriented themselves toward the West Indies. With the partial exceptions of Virginia and Maryland, they became primarily exporters of food to the Caribbean, and the extensive economic, territorial, and demographic development that they experienced up to the time of the American Revolution continued to be based on the West Indian connection. By the third quarter of the eighteenth century, a highly complex, dynamic Atlantic economy had developed, involving the colonies of several different European countries and the satisfaction of consumer demand on both sides of the ocean. Between them, the Atlantic economy of the eighteenth century and its counterpart in Asia, by now tending to be dominated by British interests, constituted a functioning global economy, the direct ancestor of the one that now exists. That economy was held together by a complex set of trade links.

Global economies and global empires were not, however, the same thing. Every European country that engaged in the Atlantic economy attempted in one way or another to establish political control over the portion of Atlantic commerce that rested on its own colonies. The imperial systems of trade controls and economic regulations (represented in the British sphere by the Navigation Acts) by which they attempted to keep the profits derived from their colonies within their nations’ own spheres required active and continuous government intervention, hence the importance of keeping colonial governments under firm central control. But the costs of maintaining such control were often high, and the costs of protecting colonies against encroachment by other empires were even higher.

Corners were frequently cut, which reduced the extent to which trade regulations could be enforced. Most of the British North American and Caribbean colonies were effectively self-governing and self-financing from their origins, which meant that until the mid-eighteenth century, the imperial policies that were regularly enforced tended to be primarily the ones in which the colonists saw benefits. Evasion of commercial regulations was widespread, largely because the realities of the Atlantic economy provided vast opportunities for profitable trade outside the legal limits of imperial systems. The French colonies were much more directly governed, but even there, the ability of trade to find its way outside imperial constrictions was quite considerable. The imperial connection was occasionally profitable to colonists, especially when it worked to reserve to them some segment of the British or French domestic market. Also, at least in the British case, the increasingly successful global aggression of the imperial state in its wars against France created significant new opportunities for trade and investment in conquered territories.

However, as is well known, the expensive success of Britain in the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), which brought British dominance in India and the practical elimination of France from imperial competition in North America, led to a concerted effort by the British government to force its American colonies into a more centralized, more coherent imperial polity, one in which the colonists’ previous ability to govern themselves and to evade unwanted restrictions was to be severely limited. With other factors, this led to the American Revolution (1775–1783), which took a large piece out of the British global empire and helped to change the nature of the Atlantic economy. Although Britain strongly reasserted itself as the world’s leading imperial power during its long wars against revolutionary France and Napoléon Bonaparte (1793–1815), the notion of a political empire that could control world trade and restrict it within the limits set by an imperial nation-state had effectively passed by the end of those wars.

During the years between 1815 and the 1870s, the notion of empire building lacked coherence in Britain and its colonies. The fact that Britain possessed a huge formal empire consisting of colonies around the world was recognized (and a source of pride to Britons), and that the empire was generally advantageous to trade, exports, and investment was recognized as well, despite the existence of colonies (such as those in the West Indies) that were rapidly moving toward economic marginality. But the vast expansion of British production that had occurred as a result of the Industrial Revolution, the growth of British investments across the world, and the realization that Britain’s best customers resided outside its colonies all led to the conclusion that there was no necessary coincidence between a growing empire made up of colonies and a growing global economy. On the whole, the British government and the British public preferred to follow policies according to which the state acted abroad in a flexible way to protect or advance specific British interests as needed by putting pressure on foreign governments to change their tariff policies, blockading the ports of countries that defaulted on their debts, sending forces to respond to attacks on British traders, and so forth. This has been called “informal imperialism,” although it does not seem to have amounted to a coherent program. It did result in the expansion of directly ruled territories abroad (especially on the borders of India, which was consolidated under British rule and greatly increased in size in the nineteenth century).

On many occasions, the British government deliberately passed up opportunities to declare new colonies, and often when it did establish them, it was a result of a slow process by which British commercial (and sometimes missionary) interests penetrated regions in which existing governments were unable or unwilling to support the kind of economic and social change the British brought with them. Colonies inhabited mainly by European settlers were regularly given self-governing status as soon as was feasible.

Other countries with rapidly developing economies but without the edge possessed by Britain tended to be more tempted to enlarge their empires deliberately before the 1870s. The United States did so by purchase and conquest, adding a large portion of North America to its holdings but eventually incorporating it all into the nation itself. France, more often motivated by domestic political considerations and by the ambitions of officials in colonial areas than by the requirements of trade, conquered Algeria, began the process of establishing a large African and Southeast Asian empire, and attempted unsuccessfully to dominate Mexico. It was not at all clear that French trade or the French economy as a whole benefited significantly from these activities, but at least they supported France’s role as a great power—a matter of considerable significance in French politics.

New Imperialism of the Late Nineteenth Century

In the 1880s and 1890s, a new wave of imperialism swept across Europe, eventually involving the United States and Japan as well. The reasons for the appearance of the “new imperialism” were complex and have been heavily debated by historians. The favored explanations include changes in the diplomatic balance of power in Europe, the effects of economic modernization on European societies, the growing complexity of European politics, and class anxiety among the bourgeoisie.

One thing that is clear is that trade in itself had relatively little to do with it. Rather, areas of the world in which the merchants of particular great (and lesser) European powers had interests came to be reconstructed in public discourse as regions in which political control had to be established to secure the economic and strategic future of the country involved. The local trading and investment interest (which was as likely as not to be in some sense multinational anyway) largely provided a focus and an excuse for political action to advance national interests. Under such circumstances, trading groups naturally tried to take advantage of the situation by portraying their own concerns as appropriate ones for state support, as when Sir George Goldie obtained British government backing in the 1880s and 1890s for establishing political control of southern Nigeria and for monopolizing the palm oil trade of the region. But on the whole, it cannot be said that the intense political competition that led to the partition of Africa and to vastly heightened international tension in the years before World War I was really about trade. And the colonial empires that emerged tended, despite all the rhetoric that had led to their seizure, not to be exclusionary with regard to trade. Most had necessarily to encourage economic development for participation in world markets as well as the national markets of the imperial countries.

In the years after World War I, after France and Britain established temporary control over much of the Middle East to facilitate the development of the area’s oil resources, systematic empire building by the old imperial powers essentially ceased. Attempts were made to convert imperial arrangements into economic systems beneficial both to the imperial state and to the colonies, a few of which (the British sterling area and the Commonwealth) had some positive economic effect. But the stresses of World War II and the clear failure of colonialism as a means of affording successful political and economic development in an era of globalization led to the rapid dismantling of the major surviving overseas empires after 1945. The attempt of Japan and the revived effort of Germany after 1933 to create empires, in part to protect themselves against dependency on the global economy, failed violently in World War II, and the undeclared effort of the Soviet Union to do much the same thing in defense of world communism collapsed in the late 1980s. The question of whether or not there will be a return to empire building in the twenty-first century remains open.

Woodruff D. Smith

See also: Colonization; Discovery and Exploration; Industrial Revolution; Portugal; Saharan and Trans-Saharan Trade; Tea.

Bibliography

Fieldhouse, D.K. Economics and Empire, 1830–1914. London: Macmillan, 1984.

Louis, William Roger, ed. The Oxford History of the British Empire. 5 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998–1999.

Parry, J.H. The Spanish Seaborne Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

Scammell, G.V. The World Encompassed: The First European Maritime Empires, c. 800–1650. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981.

Tracy, James D., ed. The Political Economy of Merchant Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

———. The Rise of Merchant Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.