Post–World War II Era

The postwar European-Asian commercial relations evolved with the vicissitudes of national politics and ideology in various Asian countries. China, where the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949 and took an anti-Western position in its foreign policy, elected to be exclusivist toward those West European industrial countries. The Chinese communist government conducted international trade (on a barter basis) essentially with the Soviet Union and its East European communist bloc until an ideological split induced a hostile Sino-Soviet relationship in the early 1960s. The colonial Asian nations won their national independence. Most of them, in trying to develop the modern economies of their own, kept active commerce with their former rulers in Western Europe. Meanwhile, a new democratic Japan gradually developed into one of the world’s major manufacturing and trading countries and a principal trade partner with Western Europe. In the 1970s, the new Asian economic powers—South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore—followed suit as prominent importers and exporters in trading with Europe. During the 1980s and 1990s, China broke away from the archetype of a state-planned economy and embraced a capitalist market economy for modernization. By reopening its market to the outside world, diversifying its production, and developing new industries, China ascended to the position of a fast-growing producer and consumer in the world. European—especially west European—trade with this largest East Asian nation experienced a quantum leap. With these new developments continuing, the European-Asian commercial relations were generally moving toward a type of market-oriented interdependence as the twenty-first century dawned.

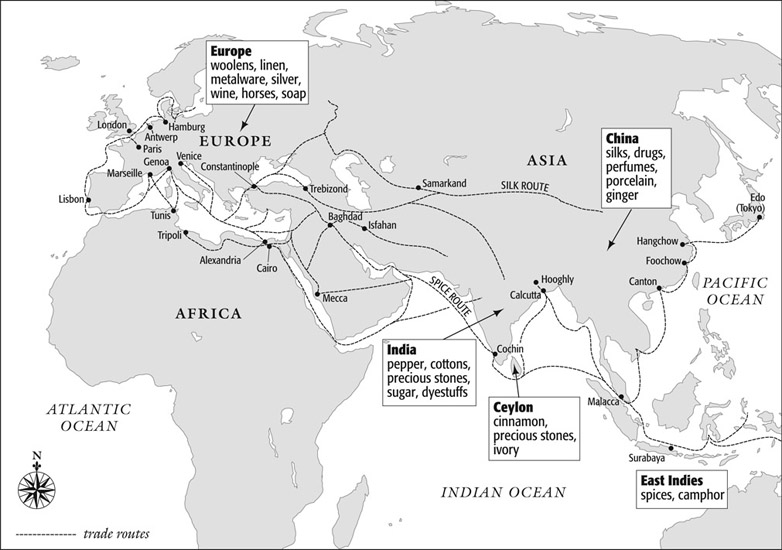

Eurasian Trade Routes, 1450 As the European Middle Ages came to a close in the late fifteenth century, overland and sea-and-land trade routes between Europe and East and South Asia were extensive. The fall of the Byzantine Christian city of Constantinople to the Muslim Turks in 1453 cut Europe off from its overland routes to Asia, forcing countries and entrepreneurs to seek all-sea routes to the East. (Mark Stein Studios)

Guoqiang Zheng

See also: British Empire; China; Silk Road.