Typically referring to the greater integration of economic activities around the world, globalization is a historical process driven primarily by human innovation and technological change.

People around the world are more closely and unexpectedly interconnected than ever before. People travel across national boundaries and over greater geographical distances more often, much faster, and under fewer restrictions now than only half a century ago. Advances in communications and transportation technologies make it possible for information and money to flow quickly and more freely through avenues hardly imaginable a quarter-century ago. New technologies enable people to organize themselves and relate to each other in novel ways. Goods and services produced in one part of the world are increasingly and more reliably available elsewhere. These are some of the key facets of a phenomenon, or a historical process, commonly referred to as “globalization.” In popular parlance, the age of globalization is also synonymous with the contemporary era. It is a historical period ushered in by the advent of satellite and electronic communications, punctuated by the end of the Cold War, and characterized by the collapse of time and space and the standardization of experience around the globe.

Origins of Globalization

Globalization, by its nature, is a vastly complex and multifaceted subject. There is no single definition of globalization agreed on among scholars, activists, and policy practitioners. Nor is there any consensus among students of globalization as to when the process began as a distinct long-term pattern in the ways individuals, groups, and societies have conducted themselves and interacted with each other. World-systems theorists, most notably Immanuel Wallerstein, argue that the processes typically meant in current commentaries by the term “globalization” are not new, as they have existed for some 500 years. The present global situation is a transition in which the capitalist world-system, which had emerged first in Europe by the sixteenth century, is evolving into something that has yet to be determined. Scholars who study the globalization of popular culture tend to locate the emergence of globalization in the latter part of the twentieth century. By focusing on a mass media–generated homogenizing world culture or by questioning its existence, their debate has loosely evolved around the notion of what anthropologist Marshall McLuhan calls “the Global Village” in his Gutenberg Galaxy (1962).

Thomas L. Friedman, an American journalist considered by some the guru of globalization, sets forth a slightly different timeframe in his agenda-setting The Lexus and the Olive Tree (2000). He argues that globalization hit the world in two waves. Round I lasted from the mid-1800s to the late 1900s, with Round II opening with the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union. The roughly seventy-five-year period from the start of World War I to the end of the Cold War can be seen as “a long time-out between one era of globalization and another.” The post–Cold War phase of globalization is clearly central to Friedman’s concept of globalization. The world in this period is driven by free-market capitalism characterized by “opening, deregulating, and privatizing,” creating an increasingly uniform global culture, and defined by new technologies: computerization, digitization, satellite communications, fiber optics, and the Internet.

In a similar vein, the globalization literature produced by global society theorists such as Anthony Giddens and Roland Robertson holds that the concept of global society has become a viable notion only in the modern age, more specifically, in the twentieth century. Sociologist Leslie Sklair sees globalization as a consequence of post-1960s capitalism powered by transnational practices in three interconnected spheres: economic, political, and cultural-ideological.

Definition of Term

The term “globalization” has also become a heavily coded word, having acquired a powerful emotive force when invoked by opinion leaders across the ideological spectrum. The concept’s celebrants tout it as a process that is highly beneficial and fundamentally benign. Less enthusiastic adherents regard it more neutrally as a key to the future, a pathway to continuous world economic development and social change. It follows from these positive views that globalization is both inevitable and irreversible. Many in this loosely aligned ideological camp tend to use globalization and Americanization interchangeably. Globalization’s detractors counter that the pro

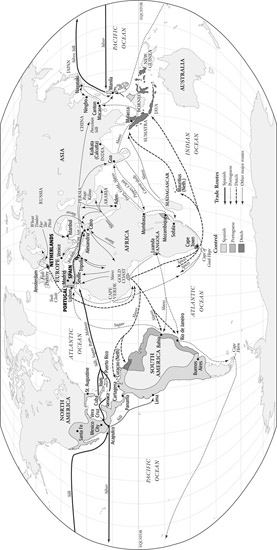

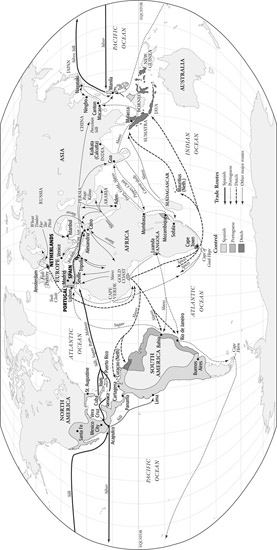

Global Economy, 1600 Globalization is nothing new, as this map of world trade in 1600 indicates. By that year, virtually all of the world, outside Australia and the remoter regions of Asia and North America, were part of the global trading network. (Mark Stein Studios)

cess is inherently detrimental. It widens inequality within and among nation-states. It exacerbates existing social injustices. Globalization, the critics argue, may create more opportunities for some people but threatens jobs and lowers living standards for others. Furthermore, globalization has corrosive effects on local ways of life and threatens to homogenize and vulgarize regional cultures.

The dissenters share a tendency to believe that globalization is neither inevitable nor a condition to which there is no alternative. Such skepticism is not the exclusive province of academicians such as Wallerstein. It encompasses former operators of institutions popularly associated with globalization, such as Joseph Stiglitz, the former chief economist of the World Bank. With these varied visions of globalization in mind, this survey highlights some aspects of globalization defined as an evolving socioeconomic system that achieved significant coherence in the latter half of the twentieth century. It also examines globalization as a cluster of cultural phenomena that have unfolded in roughly the same period.

Globalization, as the term has come into common usage since the 1980s, is a historical process driven primarily by human innovation and technological change. It typically refers to the greater integration of economic activities around the world, particularly through increased, faster-paced, and more variegated trade and capital flows made possible by advances in communications technologies, such as cheaper international telephone rates, cell phones, faxes, the Internet, and other means of electronic transactions. Globalization also means the accelerated movement of labor and information across international borders. More people now migrate across existing national boundaries aided by a greater range of affordable means and sprawling networks of transportation. In doing so, these workers carry knowledge, skills, and ideas with them. An increasing number of people now produce and deliver goods and services in and from locations farther removed from points of consumption. These human dimensions of worldwide interconnectedness create broader cultural, political, and environmental effects. In short, globalization refers to a projection beyond the borders of the modern nation-states policed by complex governing mechanisms of the type of market forces that have operated for centuries at all levels and units of human economic activity.

Since the advent of capitalism, markets have promoted efficiency through competition and the division of labor among people and their various aggregates, including national economies. Globally connected markets offer more ways for some people to tap into more and larger markets around the world and to gain access to more capital flows, technology, and labor. But markets have not necessarily guaranteed that all participants in this process equally share the benefits of improved efficiency. Nor have markets been the most reliable purveyors of social justice. This basic limitation of markets remains intact and in some cases becomes magnified in the global marketplace.

Globalization and Post–World War II Order

The twentieth century was a period of unparalleled economic growth, and global per capita gross domestic product (GDP) during this time increased almost fivefold. The strongest expansion came during the second half of the century. The United States became the engine of that massive growth because the nation came out of World War II with its economy unscathed. Buttressed by political and military alliances with this unrivaled economic superpower, many countries in Western Europe and Japan underwent a period of relatively smooth and orderly postwar reconstruction in the midcentury and embarked on a sustained economic growth after the 1960s. Nations in East Asia, most notably Taiwan and South Korea, also underwent a period of rapid economic expansion in the 1980s and thereafter. Liberalization of trade within the capitalist world took place under the auspices of the Bretton Woods institutions such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade during this period. This was typically followed by financial liberalization that gathered momentum in the industrial world in the 1970s.

Even those analysts who argue that the world economy was just as globalized 100 years ago as it is today generally agree that financial services are far more developed and the transactions are more extensively intertwined today than they were in the early twentieth century. The single most important driving force of the integration of financial markets is modern electronic communications. But the bulk of the developing countries have been largely left out of this financial integrative process until the last two decades of the twentieth century. When capital accumulated through the worldwide increase in oil prices in the 1970s was recycled to many of the developing countries, they became integrated into the global financial system as large-scale debtors. During the Cold War, nations in the communist bloc remained largely left out of the rapidly integrating global financial markets.

The twentieth century witnessed remarkable average income growth in the industrialized world, but the progress in aggregate and/or personal incomes was not evenly dispersed around the globe. The gaps between rich and poor countries, and rich and poor people within countries, grew further in the latter half of the twentieth century. The richest quarter of the world’s population comprising members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development saw its per capita gross national product (GNP) increase nearly sixfold during the century. The poorest quarter, mostly non-oil-producing nations in Africa and Latin America, experienced less than a threefold increase. Per capita incomes in Africa have, in particular, declined relative to the industrial countries and in some countries have declined in absolute terms.

Globalization in the Last Quarter of the Twentieth Century

In the last quarter of the twentieth century, this polarizing trend became more pronounced. Developing countries as a whole increased their share of world trade from 19 percent in 1971 to 29 percent in 1999. There were significant variations among the world’s major regions as well. The newly industrialized economies of East Asia and Southeast Asia did well, while Africa as a whole lagged behind other regional units. Among other variables, the composition of export factored into the widening gap. Countries that export manu factured goods recorded the greatest rise in per capita GNP. The share of primary commodities in world exports declined in the post–World War II period. This category of exports, comprising foodstuffs and raw materials, were often produced and exported by the poorest countries in the world, most of them former colonies of European empires. Various forums sponsored by the United Nations and other multilateral institutions began to address problems unique to commodity-producing countries in the 1960s. Liberalization of agricultural trade, however, remains one of the most intractable challenges today.

As political scientist Linda Weiss notes, as of 1991, 81 percent of the world stock of foreign direct investment was still concentrated in high-wage countries of the North. In a phenomenon popularly associated with the term “globalization,” a sharp increase in private capital flows to developing countries took place in the 1990s. But these private capital transfers to the developing countries have not taken place on equal terms. Critics of financial globalization argue that inter-governmental financial institutions have participated in the inequitable terms of capital transactions between the net capital exporter countries and the developing world. This typically occurs when the developing countries or nations shifting from command to free-market economies are required to privatize certain economic sectors or open them up to foreign investment as a condition for receiving loans. Assets in the newly privatized or deregulated sectors are then quickly taken over by foreign capital moving in from the industrial North, particularly the United States. United Kingdom–based American muckraking journalist Greg Palast elaborates on the mechanics of such “privatization” programs as Bolivia’s water supply systems in 2000. He charges that these cases reveal a dark side of global financial “cooperation” that is not frequently reported in the U.S. mass media.

While conversion to the free-market system has been generally arduous, not all former communist states have traveled on a rocky path to integration into the global economy. Given the diversity of experience among former communist states, some observers note that the term “transition economy” is losing its conceptual usefulness.

Countries such as Poland and Hungary are converging relatively smoothly toward performance approaching that of advanced industrial economies. Others, particularly most of the former Soviet republics, confront long-term structural and institutional challenges similar to those faced by developing countries. China also constitutes a unique case, reporting strong growth but demonstrating dramatic gaps between the vibrant and rapidly expanding state-sanctioned free-market zones and the laggard rural areas.

The composition of private capital flows from the industrial world to developing countries changed dramatically in the 1990s as well. Direct foreign investment has become the most important category of cross-border capital movement. Portfolio investment and bank credit among relatively capital-rich countries rose, but they have been extremely volatile and have fallen sharply in the wake of the financial crisis of the late 1990s. The string of financial crises that shook Mexico, Thailand, Indonesia, Korea, Russia, and Brazil suggested to some that financial crises and disruptive volatility are a direct and inevitable result of globalization. Net flows of public capital in the form of official government aid or development assistance have fallen significantly since the early 1980s. Among industrial countries, official development assistance fell to 0.24 percent of GDP in 1998 in advanced countries in contrast to the United Nations’ announced target of 0.7 percent. The overall picture thus points to the increased influence and unpredictability of private financial forces in the global capital markets, the type of relatively unregulated mass of economic force labeled by Thomas Friedman as “the electronic herd.”

Globalization and Labor

Since time immemorial, people have been moving from one place to another to find better employment opportunities and to pursue intangible values such as political and religious freedoms. The last half of the twentieth century saw an accelerated pace of the cross-border labor migration. In the period between 1965 and 1990, the proportion of the labor force around the world that was foreign born increased by about half.

This trend has been particularly conspicuous in the United States, where the changes in immigration law since 1965 have made it easier for the immediate family members of legal immigrants to move to the country. Although not commonly known, most migration still occurs between developing countries. At the same time, the increasing flow of migrants from developing countries to industrial economies in the past few decades carries several implications. First, certain economic sectors of industrialized countries will grow more dependent on continual flows of labor migration from overseas, resulting in a sharper segmentation of labor markets. Second, it may provide a way for global wages and living standards to converge. Remittances by workers to their home countries will likely play an important role in the process.

Another important implication is the sharing of skills and technical knowledge upon return to the country of origin or among fellow workers in the host country; in either venue, such sharing is facilitated by electronic communications media. Such information exchange is an integral aspect of globalization, and various agents of globalization other than individual workers and their personal networks partake in this process. For example, increased direct foreign investment means not only an expansion in the physical capital stock but also a movement of technical innovation, patent privileges, and licensing arrangements. Knowledge about production methods, marketing and advertising information, and management techniques is also dispersed to the developing countries as a result of direct foreign investment.

The ubiquity of antiglobalization sentiments in the industrialized world shows that a significant number of workers feel threatened by “low-wage economies.” The competition, either perceived or real, comes from two main sources. Laborers migrating from low-wage countries may displace workers holding less-skilled jobs in higher-wage countries. Manufacturers and producers of certain goods and services may ship their facilities wholesale to overseas locations where wages are lower, labor is not unionized, and regulatory regimes are less rigid and encompassing. This greater mobility of globalization affords private economic players to create a profound public policy dilemma. In a trend shared among industrial countries, as national economies mature, they become more service-oriented to meet the changing demands and rising expectations of their populace. While globalization alone is by no means responsible for this general trend, it quickens the speed of the shift and different socioeconomic groups within a country feel the reverberations unevenly. The concept of globalization thus generates starkly varied responses from different segments of society.

The globalization debate in the industrialized world has largely hinged on what constitutes the appropriate response to this policy conundrum. Is it the responsibility of government to try to protect particular groups, such as low-skilled workers or those employed in “sunset” industries, by controlling international trade and capital flows or adopting restrictive immigration policy? Or should governments pursue policies that encourage further integration into the global economy by accepting international division of labor but institute safety nets to soften the blow to those adversely affected by the changes? If so, what are the parameters of politically acceptable and practically feasible adjustment assistance?

Globalization and National Sovereignty

Another focus of policy debate and scholarly inquiry has been whether or not globalization reduces national sovereignty in policy making. International relations theorist Kenneth Waltz argued in his 1999 James Madison Lecture before the American Political Science Association that the nation-states will continue to display a great deal of resilience and adaptability in this regard. As a mechanism of governance, national systems still possess a range of options accompanied by coercive enforcement and, in that respect, the nation-states are unmatched by any other political entity. But does increased global integration, notably in the financial sphere, make it more difficult for individual governments to manage their domestic economic activities? Some observers emphasize, for example, the international financial market’s ability to limit governments’ options in setting domestic tax rates and designing internal tax structures. The freedom of action of each nation regarding monetary policy, too, has often been curtailed. While globalization does not necessarily reduce national sovereignty per se, it does create a strong mandate for national governments to pursue certain types of economic policies. In a world of highly integrated financial markets characterized by great short-term volatility, national governments will find it all the more imprudent to adopt policies that may threaten the nation’s financial and monetary stability and thus invite a flight of international capital. The “electronic herd” is extremely fickle and footloose.

Many students of international political economy nonetheless maintain that the nation-state will remain central to any efforts to manage the international financial markets, even though the task of stabilizing short-term capital movements must be shared with the international financial institutions, most importantly the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Some apostles of free market have expressed concern that such supranational entities place excessive constraints on private-sector business activities. Others hold different kinds of apprehension about the international institutions’ role in managing the vagaries of cross-border capital flows.

As Waltz reiterates in the aforementioned lecture, the world is fundamentally a system without centralized governance. In such a sphere, the influence of the members who possess greater capacity is disproportionately powerful since there are no effective laws or ultimate authorities to dictate or constrain them. Influential nations, particularly the all-powerful United States, can also work multilateral mechanisms to their advantage. They are capable of creating and sustaining a set of rules governing the international political economy that primarily serve their national interests. That some critics think of the IMF as another enforcement arm of the U.S. Treasury stems from those realities of power in international relations, and hence, anti-Americanism’s great appeal and resonance among antiglobalists everywhere in the world.

The question of national sovereignty is also germane to an examination of globalization’s cul tural fallout. Is globalization creating a homogenizing global culture and undermining the national state’s role as the gatekeeper of culture? Is an emergent global culture incubated in the global village eroding the basis of national and local identities? Some observers argue that a standardized world culture already exists for educated cosmopolitan individuals and privileged socioeconomic groups across the globe. Embracing similar worldviews and lifestyles, these cosmopolitans putatively form a coherent elite class united across national boundaries. They identify with one another far more than with their less sophisticated compatriots with a parochial worldview. Political scientist Samuel Huntington refers to such a transnational elite class in The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (1997). It is a disparate functional group, comprising people with careers in international finance, media, technology, and diplomacy.

Some sociologists include another type of cosmopolitan elite in this class: a global web of academicians and researchers, espousing similar ideals, curiosities, and attitudes toward political participation. They exercise influence through their affiliation with educational institutions, think tanks, international scholarly networks, and multidirectional circulation of study-abroad students and visiting scholars. Many of them are involved in the activities of nongovernmental organizations and thus project their values and agendas to the international arena by bringing to the fore such issues as environmentalism, health and food safety, the regulation of multinational corporate behaviors, and universal human rights. Antiglobalism draws much of its strength from this group as well. Most of these individuals and organizations situate themselves on the right side of the global “digital divide” and mobilize and fund-raise aggressively through the Internet.

Another type of transnational subgroups has also formed out of migrating workforces. Anthropologist Arjun Appadurai examines in detail such forces in his Modernity at Large (1996). This cadre includes not only low-skill laborers moving across national borders in search of better pay and a haven from various forms of social oppression. It also encompasses highly educated and skilled professionals who participate in the emerging transnational service sector that is relatively untethered by geographical constraints on production and delivery. For example, Appadurai’s study highlights English-speaking East Indian nationals who moved to California’s Silicon Valley and contributed to the area’s entrepreneurial energies in software engineering and e-commerce in the 1990s. A growing portion of telemarketing and billing services for U.S. corporations is now performed from locations outside the United States. Unlike transnational migrant workers of earlier times, these digital-age foreign workers tend to retain multiple home bases and remain embedded in several social networks extending over national borders. Inexpensive international telephone rates, air travel, and, most recently, e-mail make it possible for these expatriates to retain multiple allegiances.

“Global Village”

The broadening domain of shared experiences and sensual stimulation among people inhabiting the “wired” part of the world also causes national borders to thin out in matters of cultural formation. The rapid integration of visual media, particularly the worldwide diffusion of television, was a key element in McLuhan’s vaunted notion of the global village. The spread of American-style television programming and news reportage began in the early postwar period. The American television network pioneered production techniques in this new medium, and other media outlets in the industrial West largely emulated the know-how until the 1960s. Foreign aid programs undertaken by the U.S. Information Agency during the Cold War also deeply influenced the development trajectories of visual and print media in the noncommunist world.

What is newsworthy is being increasingly determined by a handful of media giants that dominate over the massively expensive communications infrastructure.

With the advent of cable and satellite broadcasting, the American-style media culture began to penetrate deeper into myriad nooks and crannies of the world round the clock. The global presence of CNN is a case in point. This geographical and temporal proliferation came in tandem with the emergence of global media conglomerates that control other aspects of the mass culture, including Hollywood studio films, music, and commercial publishing. Visual images disseminated worldwide through these conduits shape viewers’ aspirations about material culture (food and beverages, clothing and fashion, household appliances, and means of transportation) and attitudes toward such social standards as idealized beauty, acceptable sexuality, comfort, and interpersonal relations.

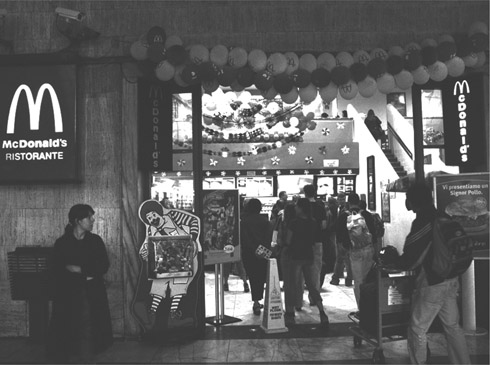

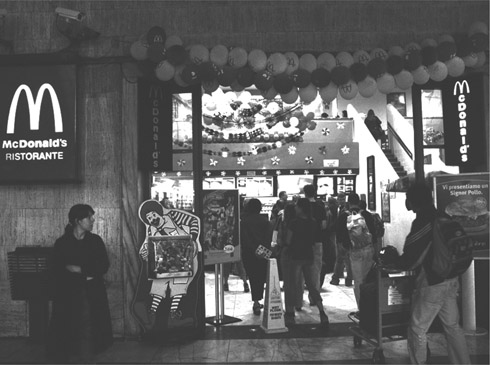

The spread of U.S. fast-food franchises around the world has become a metaphor for cultural homogenization and has often incurred the wrath of antiglobalists. Pictured here is a McDonald’s restaurant in the Santa Maria Novella train station in Florence, Italy. (© Jim West/The Image Works)

The rise of global conglomerates facilitated the standardization of other facets of individual experience, creating the illusion of a global uniform culture. The spread of American fast food franchises around the world has become a metaphor for cultural homogenization and has often incurred the wrath of antiglobalists. The missionaries of American fast food and soft drinks, such as McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and Pizza Hut, proselytized the world with a diet high in fat and sugar and a culture of throw-away packaging and utensils. The effects of the exported consumptive practices are not limited to obvious health risks. They have also yielded deleterious environmental impacts on these locales.

But culinary culture’s disseminating paths have not shepherded one-way traffic either. As historians Warren Cohen and Donna Gabbaccia note, America’s own foodways have gone through profound change, particularly since the late 1960s. Cultural anthropologists attribute Americans’ growing acceptance of “ethnic food” to various factors, including unlikely political origins. For instance, American GIs and their dependents returning from their overseas posts are given partial credit for increasing the popularity of Asian and Middle Eastern food among Americans not fitting the traditional cosmopolitan mold. The massive family driven immigration after the 1965 immigration and reform and the recent growth in intermarriage have created more diverse ethnic communities in America and thus enlarged markets for cuisine previously dismissed as too exotic.

Since the mid-1960s, the cost of international travel has dropped significantly, and foreign travel has become affordable for many middle- and even working-class people around the world. With the growth in popular tourism came the demand for hotels, food, toiletries, and recreational services that approximate, if not completely duplicate, standard American expectations. When Americans travel to any major city or tourist destination in the world, they can assuredly expect the same kinds of experience, services, and comfort levels they take for granted back home. The benefits of global standardization also extend to the minute levels to ensure the duplication of hometown experience: thanks to the uniform thickness of credit cards, they can be used at any place in the world where merchants are equipped to handle such cashless transactions.

The increasingly similar material conditions and sensory universe surrounding people in certain parts of the world are no doubt creating greater uniformity in consumption styles. It does not mean, however, that globalization is obliterating national, regional, and local identities and creating an undifferentiated global culture. There is plenty of empirical evidence presented by anthropologists, sociologists, and historians that indicate that receivers of American-style cultural wares worldwide deftly appropriate the originals and create localized variants or distinct syntheses. They often invest their own meanings into

American artifacts and practices that have little, if any, to do with the original American contexts. In Not Like Us (1997), historian Richard H. Pells depicts the subtle and complex interplay between American cultural icons and institutions introduced into Europe in the postwar period and local resistance to and reconfiguration of the American intrusions.

In a collection of anthropological essays aptly titled Remade in Japan (1992), Joseph Tobin and other contributors to the volume show how contemporary food, clothing, household furnishings, and leisure activities in Japan can be more accurately described as a pastiche of indigenous Japanese and appropriated Western elements. It is probably safe to argue that James Cameron, when he directed Titanic, never intended his handiwork to be embraced enthusiastically by aging veterans of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. But they did and used the Hollywood blockbuster as a politically safe vehicle for publicly grieving over the carefree youth and romance denied to them. The “politically safe” is the operative phrase here, however. Once the state authorities decide that such a public expression of regret for lost opportunities is disruptive and threatening, they can choke off that avenue of trafficking in invested meanings. The nation-state, in that respect, remains the most powerful arbiter of cultural politics, if not the one and only.

As people’s everyday life and sensory experience appear to converge inexorably under the rubric of globalization, local culture, identity, and the human networks that produce them remain irreplaceable. Place still matters to many people; it is just that they have greater freedom from the dictates of place. The breakthroughs in communications technology that are triggering the current unique phase of worldwide convergence and compression also permit people to hold multiple identities and embed themselves in multiple webs of human relationships without having to give up others.

Sayuri Guthrie-Shimizu

See also: Columbian Exchange; European Union; Trade Organizations; Wars for Empire; World War I; World War II.

Bibliography

Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1996.

Friedman, Thomas L. The Lexus and the Olive Tree. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2000.

Huntington, Samuel. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Touchstone, 1997.

McLuhan, Marshall. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962.

Pells, Richard H. Not Like Us: How Europeans Have Loved, Hated, and Transformed American Culture Since World War II. New York: Basic, 1997.

Tobin, Joseph. Remade in Japan: Everyday Life and Consumer Taste in a Changing Society. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. Geopoliticas and Geoculture: Essays on the Changing World System. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991.