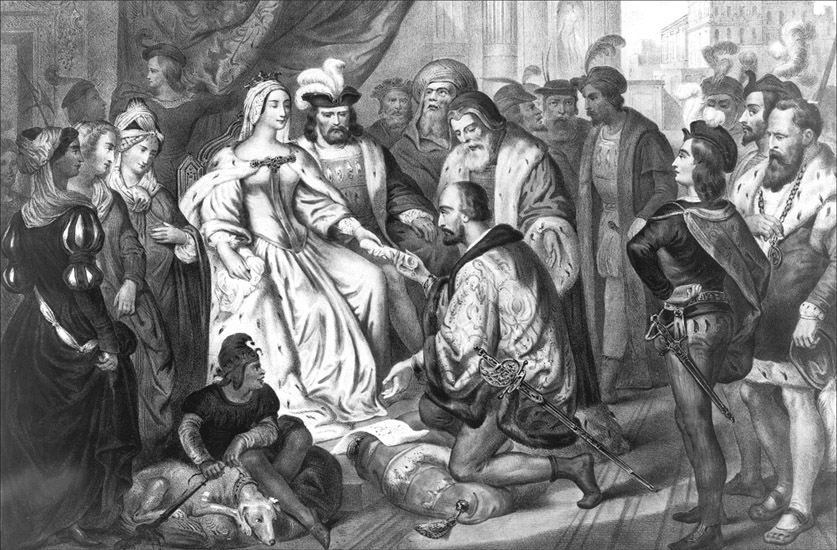

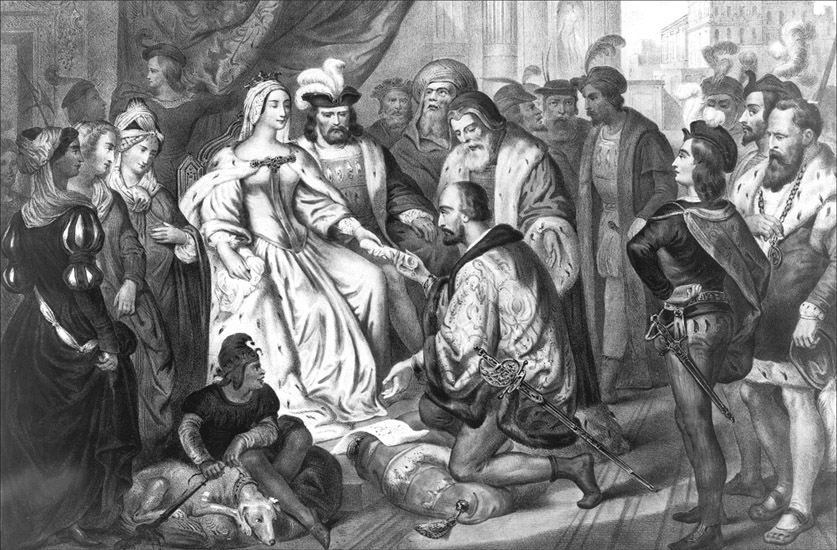

Christopher Columbus kneels in front of Queen Isabella I. The queen sponsored Columbus’s voyages to the Americas, opening up the continents to European conquest and trade. (Library of Congress)

The Spanish queen who sponsored Christopher Columbus’s voyages that resulted in the discovery of the New World.

Married to Ferdinand of Aragon, her cousin, at the age of seventeen, Isabella became queen of Castile in 1474, following the death of her older brother. She immediately went to work strengthening the Crown’s hold over Spain and launching Castile on a quest for domination of trade routes in the western Mediterranean and the Atlantic Ocean. From the beginning of her reign, Isabella insisted on royal control of all Spanish trade overseas. She held a monopoly on certain products and demanded one-fifth of the profits from other items. She improved Spain’s navy and completed the conquest of the Canary Islands. She also declared that all native peoples conquered by Spain must be treated as her royal subjects.

To unite the country under her rule, Isabella fought a series of wars against the Portuguese, the Spanish nobility, and the Moors of Granada. Victorious on all fronts, she believed that her triumphs would secure royal control of Spain and help throw back the rising tide of the Ottoman Turks, who in her lifetime had taken Constantinople, swept north through the Balkans, and now threatened Italy. As part of her efforts to unite Spain under the Crown, she introduced the Inquisition to her country to weed out false converts, or conversos, to the Catholic faith from Islam and Judaism. After Granada, the last Moorish stronghold in Spain, fell to her armies in 1492, she ordered all Jews expelled from the country.

Christopher Columbus kneels in front of Queen Isabella I. The queen sponsored Columbus’s voyages to the Americas, opening up the continents to European conquest and trade. (Library of Congress)

Following the conquest of Granada, Isabella set her sights on wresting control of trade with the Far East from the Portuguese. She was intrigued by Columbus’s plan to take Spanish ships west across the Atlantic when he first proposed it to her in 1485. Seven years later, she again invited the Genoese sailor to make his case before her court. When most of her advisors argued that the trip was unnecessary since Portugal no longer posed a threat to Spain, she turned Columbus down. However, she changed her mind at the urging of the royal treasurer, Luis de Santangel, who argued that she would live to regret her refusal to support Columbus. Vowing to sell her jewels to pay for the trip, she met with Columbus again and granted his request for three ships to sail west to the Indies in April 1492.

When Columbus returned to Spain in early 1493, Isabella moved quickly to outfit another expedition. She sent him back to the Indies in September with orders to establish a colony, search for gold, and convert the natives. Although she funded two more expeditions for Columbus in 1498 and 1502, she took ever more control of the enterprise. She appointed officials to govern the colonies and established a royal monopoly on trade. In 1503, one year before her death, she put her final stamp on Spain’s overseas empire by founding the Board of Trade, which would govern her nation’s many colonies in the New World for the next 300 years.

Mary Stockwell

See also: Spanish Empire.

Liss, Peggy K. Isabel the Queen: Life and Times. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.