Islam, a monotheistic religion with the world’s second-highest number of adherents (more than 1.3 billion, or 20 percent of the world population), was founded by a merchant.

The exact year in which Islam was founded is not clear: it varies from 570 (the presumed birth of Muhammad) to 622 (the first Hijra, when Muhammad and his followers immigrated to Medina from Mecca and from which the Muslims start counting) to 632 (the presumed death of Muhammad).

Muslims call the period before the rise of Islam as one of “ignorance” (Jaheliya). The prophet (or messenger, Rasul) Muhammad and his wife, Khadija, were both merchants traveling across the Arabian Peninsula and the Fertile Crescent. During one of his travels, Muhammad met a monk who introduced him to monotheism.

Islam originated as a religion of traders. The first followers of Islam were Arab merchants who lived in the holy city of Mecca, along with the other tribes in the Arabian Peninsula.

Soon after Muhammad’s death, the Muslim empire emerged as the “Old World’s” largest power. Until the thirteenth century, no army could stop the Muslim army in its conquest of new territories and the conversion of their inhabitants to Islam. When a Muslim army conquered an area, the Jews and Christians were allowed to retain their religion (although they remained second-class citizens in Muslim society). Followers of nonmonotheistic faiths had the choice of either converting to Islam, leaving the area under Muslim control, or being killed. Most converted to Islam.

Trade in the Muslim Empire

From the seventh to the ninth centuries, Muslims maintained flourishing trade centers. As the empire expanded, so did its trade routes. By the end of the eighth century, Islam ruled areas from the English Channel to India. The fact that the Muslim empire spread well into central Asia gave Muslim merchants control over the spice trade and other trade routes from Europe to Asia.

One of the ways in which Islam was spread to the far corners of the world was through traders who traveled to faraway destinations, farther than any Muslim army could reach at that time. The merchants not only carried goods, but also brought the new religion with them. They prosefytized in a peaceful fashion. Thus merchants, rather than soldiers, mainly responsible for the spread of Islam throughout the world.

The Qur’an, the Muslim holy book, is written in Arabic. This common language helped to unite many different ethnic groups under the Muslim empire. It also made possible the easy exchange of knowledge and ideas and the development of an impressive trading economy.

The strength of Muslim rule ushered in a period of peace and stability that enabled increased production. The development of large-scale trade was facilitated by the widespread naval and land routes, which were relatively safe, peace and political stability, and the geographic reach of the empire, which controlled the entire area between the Far East, North Africa (the first black African people to convert to Islam did so before 1050 B.C.E. in the region known today as Senegal), the Mediterranean, and parts of Europe.

The largest part of trade was exporting goods to faraway countries and importing goods from those same countries. The connection to Southeast Asia and the Far East—India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the Indian islands (Minicoy, Cannanore, Laccadive, and Amindivi), and China—was conducted in naval routes, from the ports of the Persian (Arabian) Gulf and the ancient routes by way of Afghanistan (Khyber Pass) and Central Asia. The merchants brought with them silk, spices, perfume, wood, porcelain, silver, gold, and jewelry.

As Islam continued fortifying itself and steps were being taken to convert more followers, Muslims became more and more involved in trading. For the Muslim merchants, spices became a key product of the trade industry. Spices were an easy product to trade because they were not bulky, perishable, or breakable and thus could be easily carried over long distances. For these reasons, the actual process of trading probably began with such items. Spices continued to be popular as people, early on, began relying on them to preserve food, improve their health, add taste to food, enhance their personal appearance and hygiene, and perfume their houses.

Furthermore, the characteristically Muslim impact on the spice trade was revolutionary. Before the Muslim conquest, trading had been indirect and was accomplished by local merchants who traded exclusively in their local areas. They were involved in a trade relay of sorts in which the spices were transported from one carrier to another, without any single group making the entire journey itself. When Muslim forces gained control over the trade, however, one of their first innovations was to make this trade direct, wherein Muslims would personally travel the entire length of the trade routes, without relying on intermediaries. This markedly influenced their ability to spread the word of God and Muhammad.

During this period, Muslim merchants reached Russia and took with them goods that originated from as far away as the Scandinavian countries. The merchants reached deep into Africa (before European explorers did so), and from there they brought mainly slaves and gold. The merchants also exported goods from the Muslim empire itself.

The development of vast trading networks, new methods of doing business, and the increased movement of peoples and goods increased the power of the Muslim empire (under the rule of the Abbasid and Umayyad dynasties). Jews were major contributors to the trade throughout the Muslim world and enjoyed, relatively speaking, wide freedom of belief and profession. They were able to establish contacts with people in Europe, especially other Jews, since they had a common language, base of laws, family connections, and mutual trust. This era was a golden age in both Jewish and Muslim history.

The Rise of the Ottomans and Trade in the Empire

The good trade conditions survived the collapse of the Abbasid and Umayyad empires. Muslims continued to conbine trade and religion, finding new methods of trade and converting more people to Islam. One of the tribes that converted to Islam after meeting Muslim merchants was that of the Turks. In the tenth century, the tribes of Oguz accepted Islam. Those tribes joined the Muslim armies and as time passed gained more and more power.

By the sixteenth century, the Ottoman (or as pronounced in Turkish—Ossman) empire was a recognizable force in the Muslim world. In less than 100 years, the Ottoman empire gained control over all Arab lands, forming the largest Muslim empire of the time. The economic view of the Ottoman Empire can be called “Passive Despotism Economy.” The central government had limited involvement in the market economy and focused primarily on collecting taxes.

The Ottoman empire was a land empire (rather than a naval empire such as Great Britain), and when the European Christian rivals of the Ottomans founded naval routes to the New World and India, the importance of the Ottoman Empire declined. The empire ceased expanding and therefore lacked new resources, a factor that resulted in high inflation within the Ottoman empire.

The spread of trade in the Ottoman empire brought with it developments in banking that allowed the cashing of checks across state borders. Banking was managed by non-Muslims, since Islam forbids the charging of interest.

The Ottomans maintained good relations, which included trade relations, with the European powers and the capital of the empire, Istanbul, was set half in Europe and half in Asia, and the Ottoman empire looked in both directions. Trade brought many goods from Europe to the Muslim world as well as the reverse (the most famous of these goods is probably coffee, which was introduced to the Europeans by the Turks). Nevertheless, the main basis of the economy changed from trade to that of agriculture and industry.

The Muslim world, however, was introduced to the Industrial Revolution only after it had already taken place in Europe, and the Muslim world was not industrialized for a long period—there are still some areas in the Muslim world that are not industrialized. The fall of the Ottoman empire at the end of World War I brought with it the end of the last of the large Muslim empires. In the period between the two world wars, most of the Islamic world, from Africa (including North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa) through Palestine and to Indonesia were under some kind of colonial control by foreign Christians.

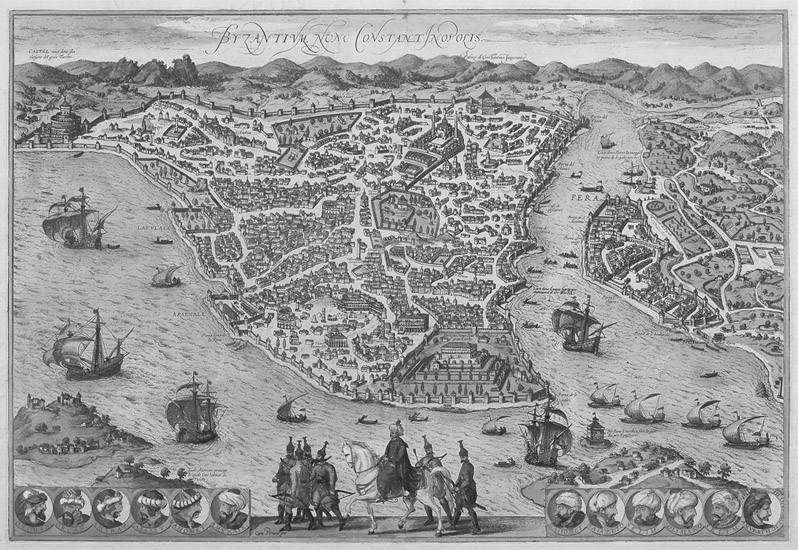

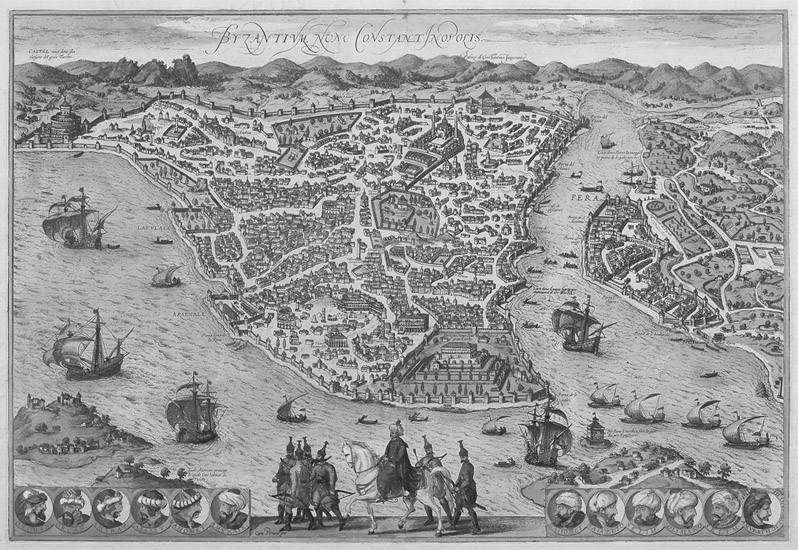

Constantinople (later Istanbul), pictured here in the 1570s, was the political, cultural, and commercial capital of the Muslim Ottoman empire. Located at the crossroads between Europe and Asia, it was for centuries a thriving center of East-West trade.

After World War II ended, many colonial states achieved independence, among them former members of the Muslim empire. Independence often replaced religion with secular politics in the 1950s, which loosened the common bond that had facilitated trade relations among Muslim countries. There was no single economic system throughout the Muslim world. All known economic theories were practiced in the Muslim world, from capitalism, to communism, to all kinds of socialist arrangements. At first, traditional rulers (with religious justifications) gained power, but soon afterward a wave of socialism swept the Muslim world (especially in the Arab countries). This movement tried to combine Muslim tradi tions, Arab traditions, socialism, and modernization (not to say Westernization), yet failed in the end to grapple with the challenges of the day.

Islamic Norms and Regulations on Trade

Inspired by Max Weber thesis, which deals with the contribution of the Protestant ethos to the development of capitalism in Western civilization’s famous researchers on Muslim society have tried to establish a thesis that will connect the basic laws of Islam with economic activity.

One of these theses establishes a strong connection between predestiny (Qadder) and the volume of economic activity in the Muslim world. According to this thesis, God (Allah) determines the future of every Muslim. In this view, the will of God, not the individual, will determine a person’s achievements in this world. The individual has no influence, and no control, over them. If the believer benefits from wealth and richness, it will not be because of his or her efforts, decisions, or actions. It seems that this idea, which has a strong place in the beliefs in Islam, would not have encouraged Muslims to make a special effort in the economic field and in trade. However, this thesis suffers from some inaccuracies, especially with the one that deals with the Muslim theological development in the first centuries of Islam.

Although Islam, like every other religion, can be interpreted in many ways, the Prophet Muhammad was clear when speaking about the importance of property rights. In his farewell pilgrimage, he declared to the assembled masses, “Nothing shall be legitimate to a Muslim which belongs to a fellow Muslim unless it was given freely and willingly.” This is a milestone in Islam and therefore any Muslim country is by definition a country that guards the rights of its citizen with regard to private property (this is implied for Muslims only). In Muslim countries, it is common to see a house surrounded by high walls with a heavy door. Behind this door and these walls, women walk around freely without being covered by their veils, and in general this house is considered private property that the government can penetrate only in extreme cases.

Islamic trade values and its inclination toward free trade could be demonstrated in the stories about Muhammad (“Hadith”), which demonstrate that Muhammad turned to the marketplace to determine the just price of commodities. When he heard that his companion Bilal had traded poor-quality dates for high-quality dates, Muhammad advised him that buying and selling at market prices over barter avoided the dangers of overcharging (ribâ) inherent in barter. After the caliphs of the early Umayyad dynasty had departed from Muhammad’s practices, the reformer Omar II ordered his governors to leave prices to the market with this advice, “God has made land and waters for seeking His bounties. So let traders travel between them without any intervention. How can you intervene between them and their livelihood?”

Islam is usually not restrictive in its trade regu lations, and many prohibitions are the product of later interpretations. Not many commodities are prohibited from being traded but include those banned from consumption (such as alcohol, which is forbidden, but could be sold to non-Muslims). Islam does not ban slavery and those nonbelievers who were captured during the wars of Islamic expansion were likely to be enslaved.

Consequently, Muslims were highly active in the slave trade from Africa, at the borders of their empire to the south and west. Muslim traders were responsible for several major routes of the African slave trade. They operated trans-Saharan routes, which passed through the Sahel on their way to Benghazi (in Libya), Cairo, Khartoum (in Sudan), and the western Saharan countries. Slaves were shipped from these destinations to Europe and eastward. In the Horn of Africa and on the eastern shores of the continent, Muslims administrated the trade across the Indian Ocean, in which African slaves were shipped to the Arabian Peninsula and to India. Muslims were less involved in the transatlantic slave trade, but Muslim leaders in the Sahel, who were eager to sell humans to the Europeans on the shore, managed to receive a special religious permission, allowing them to wage war against fellow Muslims (thus selling the captives to slavery), who were allegedly “heretic.” According to various sources, practices of slavery still exist in Sudan, as well as other Muslim countries.

However, Islam could also be perceived as restrictive in its economic attitude. Islam bans the practice of interest, leaving creditors without much incentive to lend money. In the modern period, a solution to this problem was found in the form of the establishment of Islamic banks, which follow interpretations to the laws of Islam and which allow some arrangements (such as commissions) of lending without “real” interest.

Another limitation is placed on the sale of land. Properties belonging to the Waqf (religious consecration) could not be sold or mortgaged, and the profits from the asset could not be redirected to other means than the original purpose (e.g., if someone donated the property to a school that no longer exists). Following the need to reform the landowning system, the Waqf properties were nationalized, thus releasing them to the market,

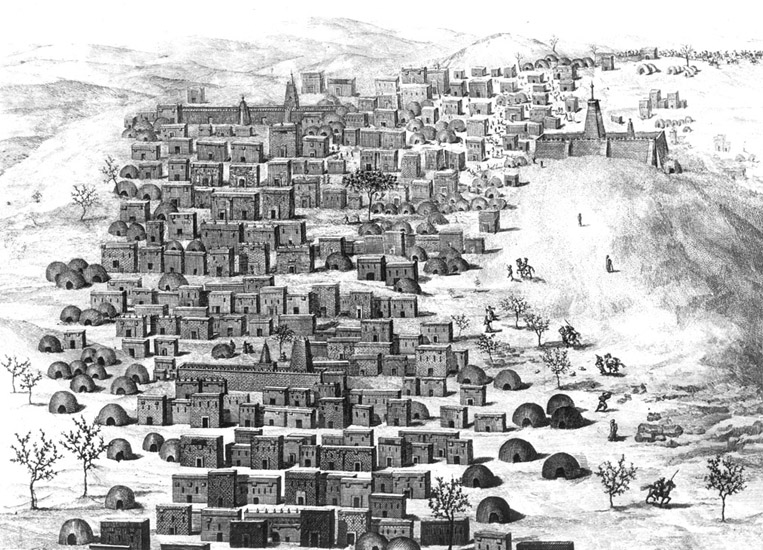

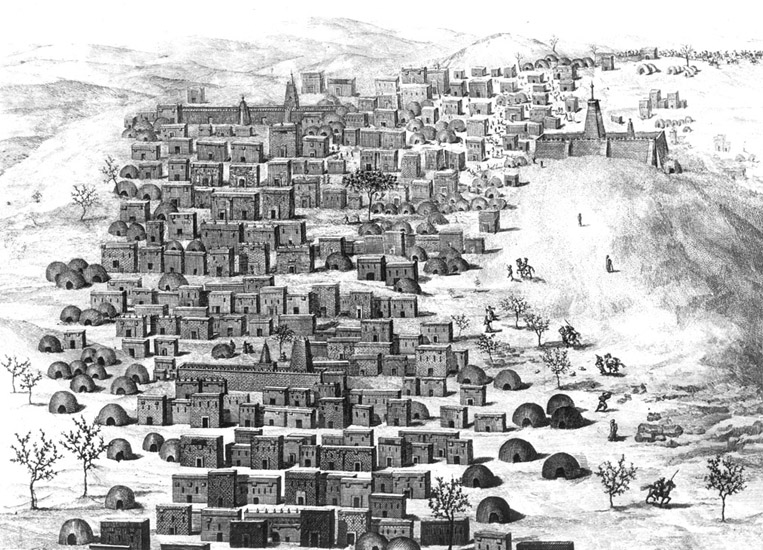

Trade in slaves, gold, and salt brought great wealth to the kingdom of Mali, linking the Arab-Muslim civilization of North Africa and the native cultures of sub-Saharan Africa. The ancient city of Timbuktu (seen here in an 1830 engraving) was a hub of trade and Islamic culture. (Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Art Library)

by governments in Turkey (1924), Egypt (1952–1957), and other countries.

The early Arabs had a strong commitment to trade and bargaining. The rise of Islam did not change, nor did it seek to change, the centrality of trade and commerce to the Arab way of life. On the contrary, the establishment of commercial law, the expansion of property rights for women, the prohibition of fraud, the call for the establishment of clear standards of weights and measures, and the uncompromising defense of property rights (even while calling for a greater responsibility for alleviating the plight of the poor and needy) pushed the Islamic civilization to the front of the world’s economic stage and made the Muslim world the defining force in international trade for over 800 years.

Tamar Gablinger

See also: Buddhism; Christianity; Missionaries; Slavery.

Bibliography

Akbar, A.S., and H. Donnan, eds. Islam, Globalization and Postmodernity. London: Routledge, 1994.

Amin, Galal A. The Modernisation of Poverty. Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1974.

Ayubi, Nazih. Political Islam, Religion and Politics in the Arab World. London: Routledge, 1991.

Braudel, Fernand. Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century: The Perspective of the World, trans. Siân Reynolds. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

Crone, Patricia. Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

Hourani, Albert. A History of the Arab Peoples. New York: Warner, 1991.

Lewis, Bernard. The Arabs in History. 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

———. The Political Language of Islam. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1991.

Lubeck, Paul M. “Islamist Responses to Globalization: Cultural Conflict in Egypt, Algeria, and Malaysia.” 2000 (http://escholarship.cdlib.org/ias/crawford/pdf/lu.pdf, accessed August 2003).

Richards, Alan, and John Waterbury. A Political Economy of the Middle East: State, Class, and Economic Development. Boulder: Westview, 1990.

Wittek, Paul. The Rise of the Ottoman Empire. London: The Royal Asiatic Society, 1971.