A natural plant that yields a highly prized blue dye that has been used for thousands of years.

The indigo plant of the Indigofera genus has over 300 varieties, but the two most often used for the production of indigo dye are the I. tinctoria (found in India and Asia) and the I. suffructiosa (found in Central and South America). The dye is extracted from the leaves of the plants through a fermentation process.

The first known use of indigo was to dye the fabric in which the mummies of the XVIII dynasty of Egypt were wrapped. Although the ancient Greeks knew of indigo and the Greek historian Herodotus mentions it around 450 B.C.E., the use of indigo remained limited until the Middle Ages. During the Crusades, Arab traders exported the dye to Egypt, Cyprus, and Asia Minor. Europeans resisted the importation of the dye since regions in Germany, England, and France were producing an inferior blue dye and the introduction of indigo would have resulted in the destruction of this agricultural industry. By the seventeenth century, the Dutch and British East India Companies began importing the dye and the demand for it exceeded the available supply. Indigo was usually used for textiles worn by royalty or for religious purposes. The British colony of South Carolina provided an additional source of indigo for Great Britain. The dye was sold to textile dyers throughout Europe. The Spanish cultivated the indigo plant in Central and South America beginning in the mid-1500s. The French indigo from Saint Domingo was of the highest quality available during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The use of indigo continued during the nineteenth century, but the dye remained relatively expensive. The wealthiest enjoyed indigo-dyed textiles with their subtle variations of shades that appeared more brilliant with age, but the average person could not afford such a luxury. Then, in 1880, Adolph von Bayer, a German, developed a synthetic indigo dye. During the last two decades of the nineteenth century, a period commonly referred to as the second Industrial Revolution, manufacturers began using chemical processes to create, improve, or substitute products. The chemical process required the transformation of naphthalene into phthalic acid and from that to phthalimide, anthranilic acid, phenylglycine carboxylic acid, and finally into indigo. Although the synthetic indigo is less expensive to produce, it lacks some of the qualities of natural indigo, such as its ability to produce subtle shading. By the late twentieth century, more than 17,000 tons of synthetic indigo was produced annually. Although some natural indigo dyes are still available, they are rare and therefore expensive.

Cynthia Clark Northrup

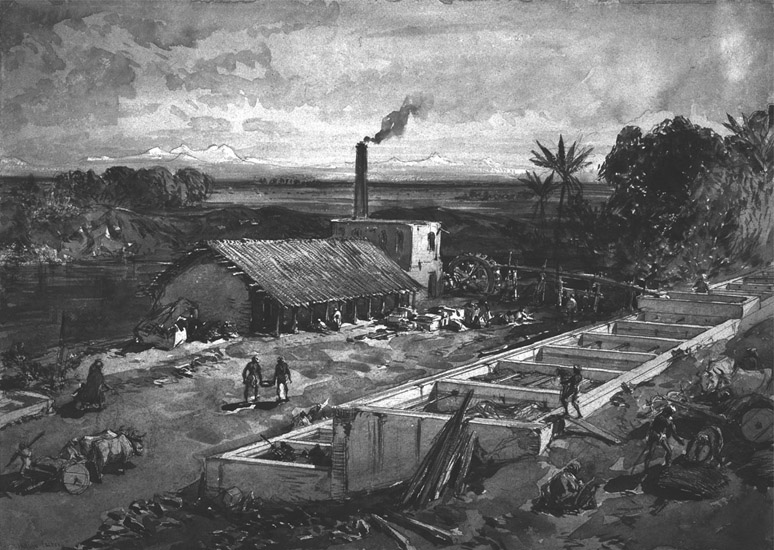

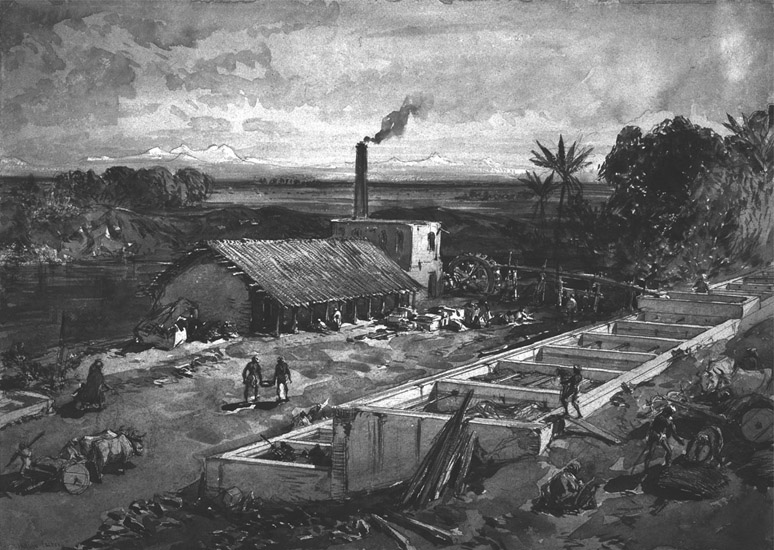

Until the invention of chemical dyes in the late nineteenth century, agricultural crops like indigo—shown here being processed at a factory in Bengal, India—were the primary coloring agents for textiles and thus were a valuable export commodity. (© The British Museum/HIP-Topham/The Image Works)

See also: British Empire; Mercantilism; Textiles.

Bibliography

Balfour-Paul, Jenny. Indigo. London: British Museum Press, 2000

“Chemistry of the Natural and Synthetic Indigo Dyes” (www.chriscooksey.demon.co.uk/indigo/index.html, accessed September 2003).

Mattson, Anne. “Indigo in the Early Modern World” (www.bell.libumn.edu/Products/Indigo.html, accessed September 2003).