A Christian military order founded after the First Crusade.

Following the successful completion of the First Crusade in the early twelfth century, a Christian religious order of men known as the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and the Temple of Solomon was founded in 1118 by a French knight named Hugh de Payens and several of his companions in Jerusalem to protect the many Christian pilgrims making their way to the Holy Land. Later known as the Knights Templar, or Templars, the men who joined the new order were both soldiers who formed a standing army for the Frankish kingdoms in the Middle East and monks who took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. The main headquarters of the Templars was a fortified monastery on the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. The order established similar outposts for military training and religious formation at places such as Haifa, Beirut, and Sidon. For 200 years, the Templars defended the roads, guarded the Holy Sepulcher, and participated in the remaining Crusades alongside such leaders as Richard the Lion-Hearted, the Holy Roman emperor Frederick I (Barbarossa), and King Louis IX of France. The Templars also joined the Crusades against the Albigensians in southern France and the Moors in Spain.

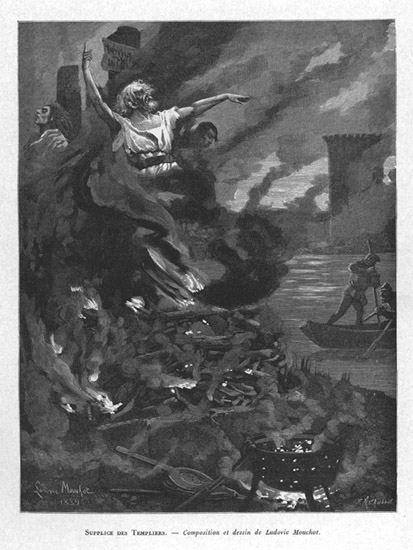

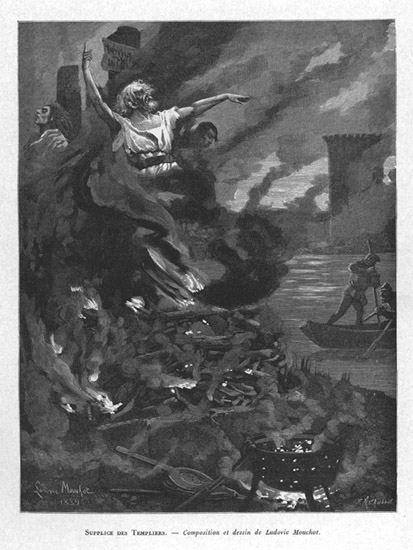

A major force in the Crusades to conquer the Holy Land for Christianity in the Middle Ages and organizers of an early banking system in Europe, the military order known as the Knights Templar fell into disrepute after the Holy Land was reconquered by the Muslims. Here, Philippe le Bel, the king of France, orders the burning of leading Knights Templar in Paris in 1314. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

The Knights Templar won wide support from the Catholic clergy and people alike for their military power and religious devotion during the Crusades. Bernard of Clairvaux wrote the rule for the order in 1128, while Pope Innocent II placed them under his direct authority in 1139. Kings, noblemen, and merchants granted them profitable estates throughout Europe that included farmland, castles, and livestock. People of every class from the wealthiest to the poorest made donations to the many fortified monasteries or “temples” that the order built in the West. Many Templars never left Europe, but instead spent their lives working on the donated land owned by their order to supply the food, arms, equipment, horses, and clothing needed by the 300 to 500 knights stationed in the Middle East.

Organization and Structure

The Templars organized themselves into three separate classes known as knights, sergeants, and priests. The knights were drawn from the nobility and wore white robes to distinguish themselves from the other classes. They came to the order already fully trained and equipped for battle. They gave up all their property on entering the order and could only leave if they promised to join another order with more stringent rules. The sergeants were mounted men who were usually drawn from the wealthy middle class. They were each granted two horses on entering the order and wore black or brown robes to distinguish their status. The sergeants were called “brothers” and acted as guards, stewards, or squires for the knights. The priests served as chaplains for the knights and sergeants and were bound to the order for life. They wore green robes and gloves at all times to keep their hands pure for the sacraments. As educated men, the priests also acted as secretaries who kept records and wrote letters on behalf of the order. After the Second Crusade, the Templars were given the right to wear a red cross on their robes.

The order developed an effective military organization that influenced the development of armies in Europe for centuries to come.

The leader of the order was known as the grand master. While his power over his fellow Templars was not absolute, his decisions were rarely questioned. He acted as the commander in chief of the order and was expected to be a fearless military leader. Many of the twenty-three men who served as the grand master of the Templars died in battle or as prisoners of the Muslims. The marshal aided the grand master in battle by acting as the field commander. The seneschal served as the chief officer of the grand master, while the treasurer oversaw the finances of the order. The draper acted as the quartermaster and was responsible for securing and maintaining the weapons, clothing, and equipment. An officer called the turcpoler commanded the light cavalry. The Templars are credited with developing a swifter cavalry than commonly used in medieval European warfare to act as advance scouts, forage for supplies, and pursue fleeing soldiers on the battlefield.

Banking

Known for their trustworthiness as well as for their courage in battle, the Templars soon developed an early banking system for the Christian West. Many kings and noblemen deposited their wealth in gold, silver, and jewels in the order’s castles throughout Europe before heading to the Crusades themselves. King Philip Augustus left the entire French national treasury at the Temple in Paris before embarking on the Third Crusade. Eventually, many noblemen, church officials, and wealthy merchants who were not planning to join the Crusades also left their treasures with the Templars for safekeeping. There could be no better place to hide wealth than in the order’s forts with their high thick walls and heavily guarded entrances.

While the Templars were not allowed to charge interest on the wealth deposited in their castles, they were able to charge fees for holding and guarding the treasures. They also made loans and collected fees as part of the transaction. The Templars made their first loan in 1149 when they granted a large sum of money to King Louis VII of France when the national treasury was bankrupt. The most famous Templar loan was made a hundred years later when the grand master of the order agreed to pay 30,000 livres to help ransom King Louis IX from the sultan of Egypt, who had captured the French king in battle. The Templars made even greater profits from their vast holdings in western Europe. Money poured into their temples from fees on their many estates and from the tithes that the pope allowed them to charge. They also ran successful export businesses, with the most profitable one being in England, where they dominated the wool trade.

As long as the Crusades continued, few were willing to question or confront the growing power and wealth of the Templars. But after the fall of Acre in 1291, the Templars and all other military orders gradually returned to Europe, where they were criticized for failing to protect Jerusalem. The Knights Hospitaller found a new role for themselves fighting Muslim pirates on the Mediterranean, while the Teutonic Knights settled along the Baltic Sea and fought the Slavs. The Templars now led by Grand Master Jacques de Molay contemplated returning to their headquarters in Paris and possibly even laying plans for another Crusade. Before the Templars could decide on the best direction for their order, King Philip IV of France decided to destroy them. Desperate for money, the king hoped to wrest control of the order’s holdings for himself and his bankrupt nation, as the yearly income of the Templars was four times greater than his own. Philip began a public campaign of slander against the order and accused the Templars of heresy, idolatry, and immorality.

Disputes with the Catholic Church

In 1307, King Philip asked Pope Clement V to investigate the Templars. When the pope agreed to begin proceedings against the order, Philip promptly arrested all the Templars in France and sent royal officers to confiscate their holdings. He hoped that Pope Clement would destroy the order throughout all of Europe. Instead, the pope determined that individual Templars would be tried in their own nation, while a council of the Catholic Church would investigate the order as a whole. The Templars were found innocent in England, Ireland, Scotland, Castile, Aragon, and the German kingdoms. They were found guilty only in France and areas under French control, such as Provence and Naples. Many of the French Templars had been brutally tortured into confessing their guilt.

Despite the pressure placed on them by the pope, the members of the church council investigating the Templars declared in December 1311 that the charges against the order were unfounded. Ignoring the decision of his own council, Pope Clement V suppressed the order in the spring of 1312 and declared that he would decide what was to be done with the Templars and their property. Philip in turn ignored the pope’s ruling and ordered the execution of Molay and several of the order’s high officials. They were burned at the stake in front of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris on March 18, 1314, declaring their innocence against all charges until the end. According to legend, Molay placed a curse on both the king and the pope by declaring that they would both be dead within the year.

While he had destroyed the Templars, King Philip was less successful in winning the order’s wealth for himself and his nation. The pope decided to turn the holdings of the Templars over to the Knights Hospitaller. King Philip was able to win a considerable settlement from the Hospitallers by claiming the Templars owed him money. However, his victory was short lived, for he died within the year along with Pope Clement as predicted in the legendary curse of the last grand master of the Templars.

Mary Stockwell

See also: Crusades.

Bibliography

Robinson, John J. Dungeon, Fire, and Sword: The Knights Templar in the Crusades. New York: M. Evans, 1991.