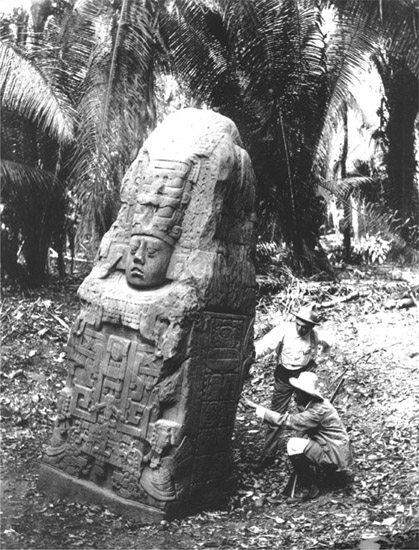

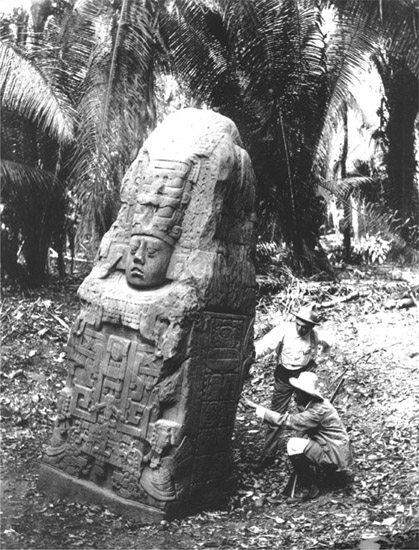

A technologically advanced civilization of Central America in the early part of the second millennium C.E., the Maya built monuments like this one at Quiriguá, Guatemala, and developed an elaborate regional trading network. (Library of Congress)

An ancient culture in the tropical rain forests of Guatemala, Belize, the Yucatán of Mexico, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador.

The Mayan civilization is known for its monumental stone architecture, elaborate hieroglyphic writing, sophisticated knowledge of mathematics and astronomy, pictorial painted pottery and carved stone, and a complex trade and economy. Hieroglyphs record historical information about the royal Maya, but unfortunately are virtually silent about Mayan economy and trade.

Some researchers believe that the southern Mayan lowlands were decentralized or segmented into some eighty independent city-states, whose royal leaders established alliances with one another through trade, including marriage and gift exchange. But other researchers regard the lowlands as more centralized, both politically and economically.

Mayan trade was carried out through two distinct economic spheres. The political economy was focused on the distribution of goods and resources for the royal and other elite Maya. The subsistence economy included food and other basic daily resources in demand by all households.

The political economy served to establish, maintain, and display the high rank and political and economic links of the elite. Trade goods tended to be highly crafted, in limited supply, and obtained from long distances through traders affiliated with the state. Scarce resources such as jade were obtained from distant locations and crafted by artisans attached to the royal Mayan palaces in lowland cities. This “attached specialization” of production also included fancy painted pottery, elaborate stone carving, and books made from local resources of high craftsmanship. There was limited distribution of the finished goods. The royal Maya controlled the production of goods in royal workshops and the distribution of the elite paraphernalia among the elite within and between Mayan polities.

The subsistence economy was focused on the household and community. Trade goods exchanged through the subsistence economy included food and resources of utilitarian value that generally were obtained locally or within a city-state. The household was the unit of production and distribution, with trading partnerships established between real or fictive kin (an affiliative family that holds an emotional regard for others) within the community or other communities to obtain goods and resources not produced or extracted by an individual household, as well as by periodic marketplace trade in the polity capital.

A technologically advanced civilization of Central America in the early part of the second millennium C.E., the Maya built monuments like this one at Quiriguá, Guatemala, and developed an elaborate regional trading network. (Library of Congress)

Archaeologists who favor the centralized model of Mayan politics and economy view the royal Maya at urban centers controlling the production and trade of goods and resources beyond simple household production for immediate family consumption. Some support for the centralization of the economy derives from scenes of Late Classic (600–800 C.E.) painted pottery vessels that depict people giving bundles of chocolate beans and other resources to a royal Maya. Could these be tribute from a subordinate community to be used by the royal Maya and their administration, including corn and other food for Mayan laborers carrying out labor duty in urban centers? In a more decentralized model of Mayan economy and politics, the control of production and trade rested at a more local level, with the urban royal Maya maintaining access to desired commodities and resources through marriage and trade alliances with local communities engaged in production.

Decentralized control of production and distribution, documented by Thomas Hester and Harry Shafer, is demonstrated by the production and distribution of chert (flint) tools from the mines at Colha in northern Belize and by the production of salt cakes in Punta Ycacos Lagoon in southern Belize, as documented by Heather McKillop. In both cases, workshops were located away from cities and near the location of the raw material. High-quality outcrops of chert at Colha were quarried to make a variety of utilitarian and elite stone tools in “household workshops,” akin to a cottage industry, and distributed to other communities within northern Belize and beyond. In contrast, the production of salt cakes in Punta Ycacos Lagoon by boiling brine in pots over fires was carried out in “independent workshops” not associated with households and in fact located away from residential communities. The salt cakes were traded to inland cities during the Late Classic period to satisfy the basic daily dietary need as well as any acquired taste for salt. The Punta Ycacos salt workshops have been submerged by a rise in the sea level that began in the Classic period. These and other salt works along the coast of Belize arguably satisfied the needs of the inland Maya of the southern Mayan lowlands during the Mayan civilization.

The rise to prominence of Chichén Itzá and other cities in the northern Mayan lowlands following the collapse of the southern lowland cities was accompanied by an increase in sea trade and the collection of salt by solar evaporation along the northern Yucatán coast. Post-Classic Mayan trade expanded to include trade with more distant lands and to include more resources, notably gold, copper, and turquoise. By the Late Post-Classic period (1200–1500 C.E.), the Maya belonged to a Mesoamerican world system and used chocolate beans as currency.

The distribution of exotic trade goods at sites within the Mayan lowlands indicates that trade goods were transported by water and by overland routes. Sea trade was accomplished in dugout canoes and although none have been preserved, small boat models are preserved at Altun Ha, Moho Cay, and Orlando’s Jewfish site. There are pictorial depictions of canoes with paddlers from a royal tomb in Tikal’s burial 116 in Temple 1 and elsewhere. Overland trade used human porters, as witnessed by the sixteenth-century Spanish conquistadors and necessitated by the lack of suitable domestic animals as beasts of burden.

Reconstructing the routes and mechanisms of Mayan trade requires estimation of the origin of local and more exotic goods and resources, which are variously easier or more difficult to assign to their place of origin. The distribution of resources within the Mayan lowlands meant that some materials (such as granite from the Mayan mountains, which was used to make metates for grinding corn), were closer to some communities than others. Artistic depictions on painted pots and stone carvings indicate that jaguar pelts, macaw feathers, and other rainforest products were traded. Generally, goods and resources for the political economy of the royal Maya were more exotic and included obsidian, basalt, and volcanic ash (for tempering pottery vessels) from volcanic regions of Mesoamerica, gold from lower Central America, and jade from the Motagua River basin in Guatemala. Additional Post-Classic exotics included, for example, copper from Honduras and central Mexico, turquoise from northern Mexico, and Tohil Plumbate pottery from Pacific Guatemala. Salt, granite, chert, limestone, pottery vessels, and some foods were traded within the lowlands.

Heather McKillop

See also: Archaeology; Art; Aztecs; Chocolate; Copper; Corn; Egypt; Gold; Incas; Jade; Marketplaces; Pottery; Salt; Water.

Andrews, Anthony P. Maya Salt Production and Trade. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1983.

Aoyama, Kazuo. Ancient Maya State, Urbanism, Exchange, and Craft Specialization. 12. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 1999.

Graham, Elizabeth. The Highlands of the Lowlands. Madison, WI: Prehistory, 1994.

Hester, Thomas R., and Harry J. Shafer, eds. Maya Stone Tools. Madison, WI: Prehistory, 1991.

McKillop, Heather. In Search of Maya Sea Traders. College Station: Texas A&M Press, 2002.

———. Salt, White Gold of the Ancient Maya. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Martin, Simon, and Nikolai Grube. Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2000.

Masson, Marilyn, and David Freidel, eds. Ancient Maya Political Economies. New York: Altamira, 2002.

Reents-Budet, Dorie. Painting the Maya Universe. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1994.