Breakthroughs in the art or practice of curing humans have been stimulated as a result of the development of long-distance trade that brought with it the introduction of new diseases and medical knowledge from other cultures.

When isolated clusters of people foraged for food in their remote hunter-gatherer environment, the risk of disease remained small. As the ancient civilizations along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers brought people into closer contact with each other, disease occurred but not with the devastating effect of later centuries. Some medicine was practiced, although the extent of the treatments have not survived in records other than in the Laws of Hammurabi (from the Sumerians), which contains the first known code of medical ethics and established a fee schedule for specific procedures, including surgery.

The ancient Egyptians, like the Hittites and the Sumerians, remained fairly isolated from other cultures. Trade occurred between the different regions but was usually conducted by a limited amount of men, and the length of the journey was longer than the period of incubation for most diseases. The ancient Egyptians practiced a rudimentary form of medicine. Lacking an understanding of the human anatomy, they did not focus on surgery but instead employed a variety of drugs and other substances, such as castor oil, senna, opium, colchicine, and mercury to cure ailments. The ancient Egyptians also had advanced embalming skills.

As trade spread throughout the eastern Mediterranean, medicine began to develop, especially as a response to war. Homer records the first known account of medical treatment for injuries in The Iliad, in which he describes more than 150 different types of wounds. In one particular account, he notes that an arrow penetrated a warrior in the right buttock, missed the pelvic bone, and entered the bladder, resulting in death. The account reveals the extent of Greek knowledge of human anatomy. Medical treatment, however, usually consisted of simply trying to keep the wounded patient comfortable. One account in The Iliad involved a doctor named Machaon, who, after being wounded, treated his injuries with a cup of hot wine with grated goat cheese and barley sprinkled on top. The Greeks had learned some of their use of herbs and drugs from the Egyptians and routinely incorporated this knowledge into their practice of medicine.

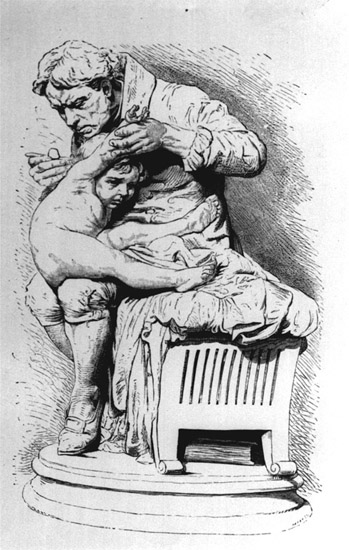

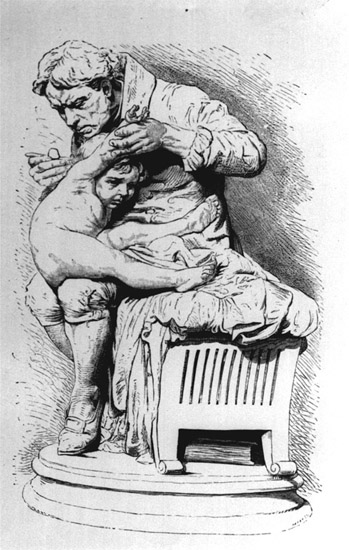

By the end of the eighteenth century, Dr. Edward Jenner was able to cultivate a serum that led to the worldwide eradication of smallpox. Jenner is pictured here inoculating a child. Because of his medical breakthrough, smallpox no longer posed a threat to merchants who traveled the world. (Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine)

By the sixth century B.C.E., medical schools had been established to further the wisdom of the physicians. One of the most prominent physicians to come out of these schools was Hippocrates of Cos. Hippocrates believed that to diagnosis and treat a patient, one first had to observe the patient to deduce what form of ailment was present. Treatment often included a regimen of diet and exercise. Several of his students traveled through northern Greece recording their observations of the people, their constitutions, and illnesses. These works remained scattered throughout Greece until the librarians at Alexandria attempted to collect them all after the death of Alexander the Great. Hippocrates inspired his students and is credited with much of their work in addition to his own. The physicians’ Hippocratic Oath is named for him.

During the age of Pericles, when Athens was at its height of power at the head of the Delian League, a plague struck the city with devastating results. The historian Thucydides recorded the spread of the disease from 430 to 427 B.C.E. He noted that there had been no illness that year until the plague struck and indicated that the origin of the mysterious disease was Ethiopia. Traders traveled between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Libya, then sailed into the Athenian port of Piraeus, and from the port the disease spread through the city of Athens. At the time, Athens was overcrowded because much of the rural population had moved to the city to seek refuge during the Peloponnesian War.

Thucydides observed that the symptoms started with “strong fevers, redness and burning of the eyes, and the inside of the mouth, both the throat and tongue, immediately was bloody-looking and expelled an unusually foul breath. Following these came sneezing, hoarseness … a powerful cough … and every kind of bilious vomiting … and in most cases an empty heaving ensued that produced a strong spasm that ended quickly or lasted quite a while.” The flesh became “reddish, livid, and budding out in small blisters and ulcers.” Most of the victims died in the second week of the illness, while others lingered but experienced severe bowel problems, including ulceration and diarrhea, before they died. Physicians who attempted to attend the sick contracted the disease themselves. Ancient physicians failed to discover what the disease was, but modern health research ers postulate that the disease might have been a strain of Ebola. The Plague of Athens marked the end of the golden age of Greece. Even though Greece’s power had begun to decline, Aristotle advanced medical knowledge of anatomy through animal dissections.

Gradually, the Roman empire consolidated control over the eastern Mediterranean as well as the rest of the known world. Trade flourished throughout the empire, but even the health-conscious Romans were not immune to the spread of plagues. Merchants and soldiers traveling from all parts of the empire helped to spread diseases. The Roman empire, stretching from Britain to India, relied on the ability to move troops to all parts of the realm within a short period. Soldiers were employed in constructing roads and bridges as well as viaducts that carried fresh water to the cities. Silver water vessels prevented the contamination of stored water and the availability of Roman baths produced a generally clean population. Grain was regularly imported, as were a variety of other foodstuffs. Ambassadors traveled east to China, but each culture had developed a resistance to disease from the other. At the time, the Roman empire under the reign of Marcus Aurelius had reached a population of approximately 54 million people, while Han China had 59 million people. Troops moved regularly throughout the Roman empire, either for protection or to expand the borders through warfare.

Troops returning from Mesopotamia in 165 C.E. brought with them a disease that historians believe was either smallpox or the measles. Until then, the only diseases known in the Mediterranean region were malaria, mumps, influenza, diphtheria, and tuberculosis. In affected areas, 25 to 33 percent of the population died, but the real change that occurred was that the Roman army ceased further efforts to expand eastward, which subsequently ended attempts to establish a direct trade route from China to Rome. It was the first time that Rome had failed to retaliate immediately against barbarians who attacked the borders of the empire. Physicians were unable to prevent the spread of the disease, which lasted until 180 C.E.

Another plague occurred in 251 and lasted until 266 and is commonly referred to as the Plague of Cyprian, after the bishop of Carthage. During this outbreak, 30 percent of the population in affected areas died. In Rome, more than 500 people died each day, forcing a change in imperial policy. Negotiations began with barbarians, who then served in the Roman army, and those who tilled the soil were tied to the land in an effort to maintain the production of food.

The last of the plagues that affected the Roman empire occurred in 542 and is known as the Plague of Justinian. Sweeping across the empire at a time of crisis along the borders, the disease wiped out 33 percent of the population. Invasions and political instability followed, along with the disruption of trade as the Western Roman empire, starting with the sack of Rome in 476, fell to barbarian forces.

The only advancement in medicine during the period involved the work of Galen (129–c. 216). Born in Greece, Galen served as the court physician under Marcus Aurelius. He compiled previous medical knowledge in all fields and correlated all the information with his own discoveries, which were based on experimentation and dissection of animals. He discovered that the arteries carried blood, not air, and provided information about the brain, spinal cord, nervous system, and pulse. Unfortunately, his work was so revered that it remained unchallenged until the sixteenth century, when researchers realized some of his errors.

Middle Ages

Throughout the Dark Ages, medicine advanced very little in Christian Europe. Islamic scholars managed to preserve many of the ancient Greek texts on medicine as well as other subjects, and the reemergence of this knowledge sparked the Renaissance. Unfortunately, the invasion of the Mongol hordes throughout Russia, eastern Europe, and the Middle East led to another medical crisis. One of the requirements for Mongol commanders was that they never leave the field of battle without achieving victory. However, if the khan died, all Mongols were required to return to their home country to elect a new leader. In 1346, a Mongol commander had laid siege to the city of Kaffa, on the Black Sea. The city was equipped with an underground water supply and adequate provisions, and after a long siege the commander received word that he had to return to Mongolia to elect a new leader to succeed the one who had just died. During the siege, many soldiers died of a mysterious disease. So that he could end the siege and return to Mongolia, the commander catapulted the decaying corpses of his men over the wall around the city, and the disease spread throughout the population, forcing it to surrender. Rats ate the corpses and eventually made it on board ships headed for Genoa and Venice. With up to half the population of some regions in Europe succumbing to what became known as the Black Death, physicians were powerless to combat the new disease. The only perceived preventive remedy appeared to be for unaffected individuals to put posies in their pocket to ward off the disease, hence the nursery rhyme “Ring around the rosies, a pocket full of posies.” The plague continued to affect the population of Europe until the seventeenth century.

Early Modern Age through the Nineteenth Century

In the meantime, explorers like Christopher Columbus had spread other diseases such as smallpox to the New World. Although the incubation period for smallpox was only twelve days, many of the sailors on board the ships carried the disease in their scabs. The indigenous population was decimated by the disease, with estimates of the number of fatalities ranging as high as 95 percent of the local populations. Although Europeans remained susceptible to smallpox, most had acquired some immunity to the disease. Since children were most susceptible to the disease, they remained at the greatest risk.

In 1717, Lady Mary Wortley Montague arrived in Istanbul with her husband, the British ambassador, where she observed young children being given a mild dose of smallpox by injection, whereby they developed immunity to the disease. She relayed the information to medical professionals in England on her return, and by the end of the eighteenth century, Edward Jenner was able to cultivate a serum that led to the world-wide eradication of the illness. Because of medical breakthroughs, smallpox no longer poses a threat to merchants who travel the world or to the populations that they visit.

Another disease that sailors encountered during the age of discovery was malaria. Portuguese explorers charting the coast of Africa found that malaria prevented them from penetrating the interior of the continent. As a result, slave traders and merchants had to conduct all business through intermediaries along the coast. The discovery of quinine in the nineteenth century allowed Europeans to control the disease, and a scramble for colonies in Africa began.

Medical experiments also allowed for the successful completion of the Panama Canal, a feat that decreased the distance for goods to be shipped from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast of North America by 8,000 miles. The death of French workers from yellow fever, along with technological difficulties, had prevented the French from successfully completing the canal and forced them to sell their assets to the United States. Army surgeon Walter Reed had conducted experiments on the cause of yellow fever in Cuba after the Spanish-American War (1898). His team, working from prior research, concluded that the mosquito was the carrier of the disease and that the incubation period was twelve days. The spraying of mosquitoes eliminated outbreaks of yellow fever on the island of Cuba, and the army later used this information to protect workers constructing the Panama Canal.

Twentieth Century

While these are a few examples of the changes in the field of medicine brought about through the course of trade around the world, medicine has mushroomed into a huge industry since the twentieth century. The globalization of the world economy and the speed of travel have exposed the world to a greater risk of disease. At the same time, modern medicine, beginning in the eighteenth century, has offered solutions to many common diseases. Research and development continues on new diseases such as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

Since AIDS became a worldwide problem in the 1980s, pharmaceutical companies have invested billions of dollars in research to develop drugs to prolong the life of those with the disease. By 1999, the average cost of drugs for AIDS patients amounted to $22,000 per year. While health care insurers covered much of the cost for AIDS patients in the United States, the continent hardest hit has been Africa, where the average government expenditures per year for health care amount to under $100.

In 2003, President George W. Bush, in his state of the union address, announced a major policy initiative that would provide low-cost drugs to African countries to combat AIDS. Other countries, such as Brazil, have analyzed the drugs and began producing their own in violation of patents filed in the United States. The World Trade Organization continues to try to address this issue.

SARS, another recent disease, caused a reduction of travel between China and the West. Scientists are still working on a vaccine for SARS, which means that quarantine remains the most effective means of preventing the spread of the disease at this time. As long as worldwide trade continues, the risk of new diseases decimating large segments of the population will remain and medical professionals will continue to explore new methods for preventing epidemics.

Cynthia Clark Northrup

See also: Bioterrorism; Black Death; Columbian Exchange; Disease; Greek City-States; Roman Empire.

Bibliography

Bean, William Bennett. Walter Reed: A Biography. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1982.

Davis, Evan. “Facing the Cost of AIDS.” BBC News (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/3223567.stm, accessed January 2004).

Groh, Lynn. Walter Reed: Pioneer in Medicine. Champaign, IL: Garrard, 1971.

Ferguson, Arthur C. “Plague Under Marcus Aurelius.” May 30, 1999 (http://omega.cohums.ohio-state.edu/mailing_lists/LT-ANTIQ/1999/05/0064.php, accessed January 2004).

Olson, P.E., et al. “The Thucydides Syndrome: Ebola Déjà Vu? (or Ebola Reemergent?)” Emerging Infectious Diseases 2, no. 2 (April–June 1996) (www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol2no2/olson.htm, accessed January 2004).