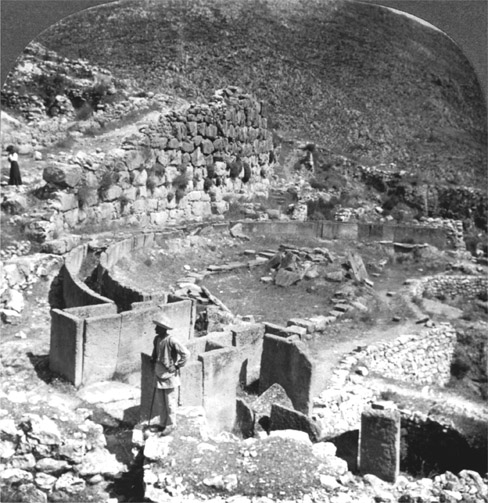

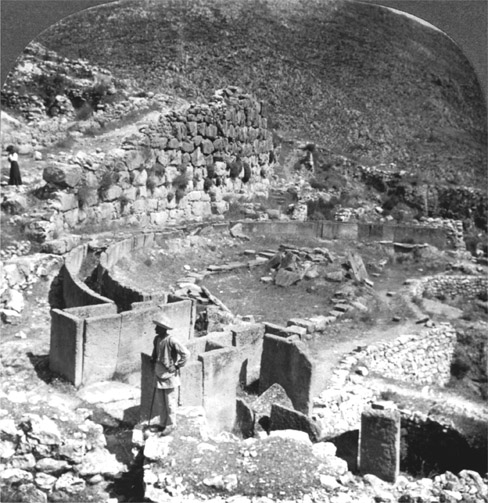

Shown here are the circular royal tombs of Mycenae in southern Greece. An early trading civilization of the eastern Mediterranean, the Mycenae date from the latter centuries of the second millennium B.C.E. (Library of Congress)

An ancient Bronze Age civilization located in south central Greece that prospered from 1400 to approximately 1125 B.C.E.

The ancient Mycenaean civilization consisted of a group of loosely confederated city-states that included Tiryns, Pylos, Thebes, Orchomenus, and Mycenae. A monarch ruled in Mycenae. He relied on the assistance of a well-developed group of bureaucrats who maintained precise records of land, inventories, commodities bought and sold, and distribution of materials. Most of the inhabitants of the kingdom were soldiers (since the Mycenaeans were warriors) and peasants or slaves who worked the land and produced the cloth and other items for use or export.

Shown here are the circular royal tombs of Mycenae in southern Greece. An early trading civilization of the eastern Mediterranean, the Mycenae date from the latter centuries of the second millennium B.C.E. (Library of Congress)

The Mycenaean rulers engaged in raids throughout the eastern Mediterranean and Asia Minor. They conquered the island of Crete and attacked the ancient city of Troy—a siege that Homer recounted in his Iliad and Odyssey. Hittite records reveal that the Mycenaean people also attacked areas in the Near East. During these raids, they captured slaves that were brought back to central Greece to produce the agricultural goods later traded throughout the rest of the eastern Mediterranean region from Egypt to Italy.

The Mycenaean traders exchanged goods throughout the eastern Mediterranean region. Imported goods included ivory and gold, much of which has been rediscovered in the ancient burial tombs. Royal women were often buried with gold diadems and men with gold masks. Other imported goods included ostrich eggs, glass, metals such as copper and tin, jewelry (lapis lazuli), and dyes. A fourteenth century B.C.E. shipwreck off the coast of Turkey that was destined for Mycenae included a cargo that contained 354 copper ingots, blue glass, tin, pottery from a variety of regions from the Levant to Egypt, terebinth resin for dyeing, and bronze implements. Amber from the Baltic Sea has also been discovered in Mycenae but was probably used as a medium of exchange with another civilization in the eastern Mediterranean instead of directly between the Baltic Sea merchants and Mycenae.

The demise of Mycenae occurred quickly. Archaeologists have discovered that the buildings including the Citadel had been burned, which leads to speculation that the Sea Peoples or the Dorians might have attacked the city and burned it. Other scholars argue that a natural disaster such as an earthquake or a famine might have resulted in the abandonment of the city. Whatever the reason, Mycenae remained uninhabited from 1200 B.C.E. until Heinrich Schliemann, an amateur archaeologist, discovered it in 1870. Schliemann used Homer’s Iliad to pinpoint the location of the city. His persistence paid off when he discovered the burial tombs of the ancient kings. These tombs contained cups, jewelry, pottery, bronze weapons, and gold items. The tomb of one king yielded a thin gold mask that Schliemann believed to represent the face of the famous King Agamemnon, who had defeated the city of Troy in the Trojan War.

Much of the documentary evidence concerning Mycenae has been preserved in the Linear B tablets found in the ruins. Linear B script remained untranslated until 1952, when British architect Michael Ventris finally deciphered it. Although the tablets yield much about the structure of the society and the operation of the palace, they do not reveal extensive information about trade. The few references that can be found mention cloth that was being stored for export. Other export items were wine, olive oil, and wool.

Cynthia Clark Northrup

See also: Linear B Script; Minoan Civilization.

French, Elizabeth Bayard. Mycenae, Agamemnon’s Capital: The Site and Its Setting. Charleston: Tempus, 2002.

Palmer, Leonard Robert. Mycenaeans and Minoans: Aegean Pre-history in the Light of the Linear B Tablets. New York: Knopf, 1962.

Starr, Chester. A History of the Ancient World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.