The Continental System

The Continental System involved a blockade of Britain from its European trading partners and its colonies. Napoléon wanted to paralyze Britain by destroying its commerce. Britain would become an isolated nation.

The Berlin Decree of November 21, 1806, formally initiated the Continental blockade. In the preamble, the decree indicated that England did not acknowledge international law, that it treated all foreigners as enemies, and that it extended the right of capture to merchant vessels, merchandise, and private property. The decree itself stated that the British Isles “are in a state of blockade, that all trade or communication with them is prohibited” (Articles 1 and 2). “All trade in British goods is prohibited and all goods belonging to England or coming from her factories or her colonies are declared to be fair prize, half of their value to be used to indemnify merchants for British captures” (Articles 5 and 6). The final article stated, “[E]very vessel coming from direct ports of Great Britain or her colonies, or calling at them after the proclamation of the decree, is refused access to any port on the continent” (Article 7). The significance of this decree is that, for the first time, a number of actions, which had already been occurring, became formalized in law.

Napoléon issued this decree immediately after his victories over the Prussian army at the Battles of Jena and Auerstädt on October 16, 1806. He claimed to be retaliating against the British for their blockade of the entire coast of Europe from the Elbe River to Brest. He insisted that this British blockade, illegal and unenforceable, remained a paper blockade. According to the emperor himself, this blockade and isolation of Britain was intended “to conquer the sea by power of the land.”

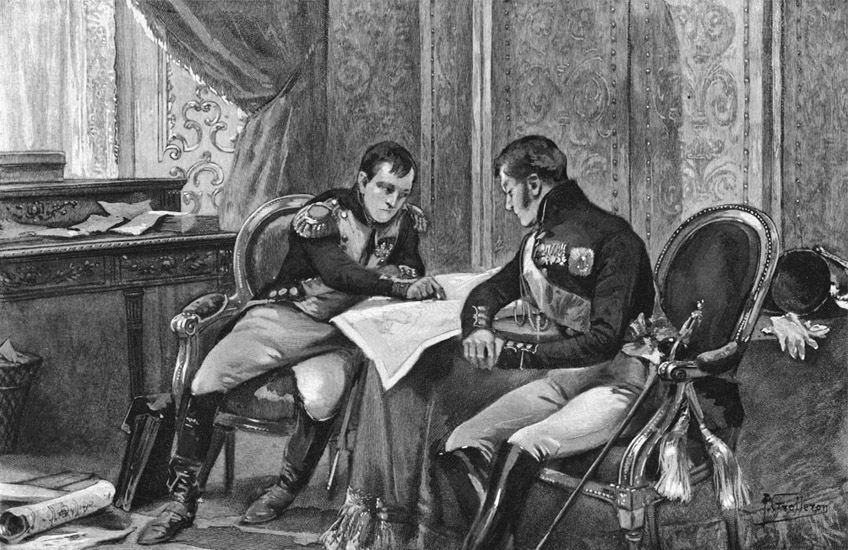

Napoléon Bonaparte and Tsar Alexander II negotiate the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807. The treaty proved effective in closing continental Europe to British trade. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Napoléon issued a number of subsequent decrees: the Warsaw Decree, the Milan Decree, the Fontainebleau Decree, and the Rambouillet Decree, all of which reiterated and expanded the Berlin Decree. The Warsaw Decree of 1807 extended the Berlin Decree. The Milan Decree, issued at the end of 1807, declared that any ship complying with the British Order in Council would be considered “denationalized” and thus be open to search and seizure by the French. The Fontainebleau Decree of October 18, 1810, allowed for the seizure and burning of any British goods found on the Continent. The Rambouillet Decree of March 23, 1810, directed against the United States, ordered American ships sold with their cargo.

Napoléon believed that Britian’s loss of trade and precious metals would ruin English credit and destroy the Bank of England. This did not happen. The British retaliated against the French punitive decrees with their own: these included the three Orders in Council (November 11 through December 18, 1807), which forbade any nation that adhered to the Berlin Decree to trade with England. The Orders in Council, meaning that they were issued without Parliament’s consent, gave the British the right to search the contents of any neutral ship that landed in Britain. The British extended their old 1756 Rule to coastal shipping between enemy ports from which English ships had been excluded. In effect, this created a counterblockade that affected not only the countries allied to France, but also neutrals such as the United States. Napoléon responded with his Milan Decree, stating that these ships, which called into port in Britain and allowed themselves to be searched, became British and thus could be seized by France.

Although initially targeted against Britain, the Continental System involved all of Europe, including neutral countries as well as Europe’s trading partners such as the United States. The English bombarded neutral Copenhagen in 1807 and seized a Danish fleet. Amsterdam, which had previously been a major port, declined because of the blockade and never regained its previous significance. The Russians were also involved and had agreed to join the blockade as part of the Treaty of Tilsit (July 7, 1807). As part of this peace, the two powers agreed that if the Scandinavian country of Sweden remained neutral, Russia had the right to declare war on it and take Finland as compensation. This took place. Prussia stopped trading with Britain and closed its ports. The Treaty of Tilsit proved effective in closing continental Europe to British trade. Relations between France and Russia broke down at the end of 1810. Tsar Alexander II began opening up Russian ports to neutral ships because of the negative impact of the blockade on Russian trade. Napoléon invaded Russia in June 1812.

Napoléon also became embroiled in a war with the countries located in the Iberian Peninsula over the blockade. Portugal had continued to import British goods. Napoléon sent his armies through Spain to reach Portugal and thus began the Peninsular War that lasted from 1808 to 1813.