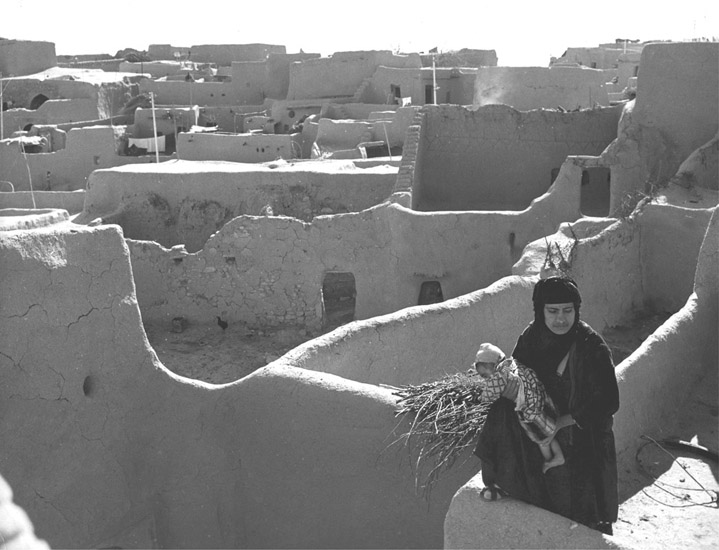

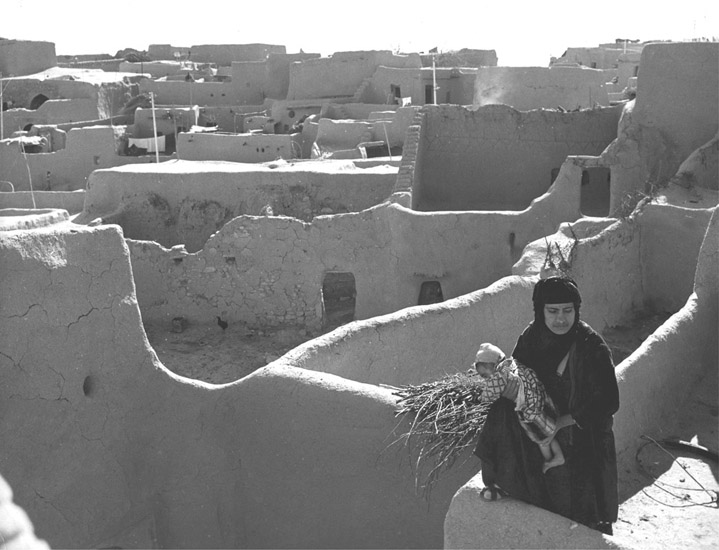

The ancient Mesopotamian city of Nineveh (in modern-day Iraq) was the capital of the Assyrian empire and a major trading hub from the eighth to the sixth centuries B.C.E. (© Topham/The Image Works)

The ancient capital of the Assyrian empire, located on the Tigris River.

Sir Austin Henry Layard discovered the remains of Nineveh in the autumn of 1847. The ruins lay quietly nestled about 1,500 yards from the banks of the Tigris River, just across from the city of Mosul, Iraq. Layard first uncovered the palace of Sennacherib, the king of Assyria, who ruled in the mid-seventh century B.C.E. According to George Smith, the southwestern inner city wall was 2.5 miles long. It joined the northwestern inner city wall, which was a shorter 1.3 miles long. The Old Testament describes Nineveh as an “exceeding great city of three days’ walk across” and built by Nimrod. Of course, this was not the inner city wall, but the entire district of Nineveh that was probably thirty to sixty miles across. Sennacherib moved the capital of Assyria from Dur Sharrukin to Nineveh and set himself to build a city unrivaled by any other in the ancient Near East.

Near the headwaters of the Tigris River, Nineveh functioned as a gateway from the mountains to some of the most fertile plains in the Near East. The city was the capital of the Assyrian people from the late eighth century to its destruction by the Medes and Babylonians in 612 B.C.E. Sennacherib left a history of the city on a cylinder dating his expedition to the city of Tarsus. He describes Nineveh as having around fifteen main gates situated in the city wall, five of which have been excavated. Each gate was guarded by two huge lamassu (human-headed-and-winged bulls). The inner city wall overlooked a plantation, which is said to have yielded plants from around the entire Near East, but especially wheat, barley, and grapes. The plantation was sustained by a complex system of conduits that watered the fields year round, the largest was called the Jerwan Aqueduct. The aqueduct redirected the Khosser River to Nineveh and is one of the earliest examples of such a structure. Part of the aqueduct system, an ogival arch, still remains today in Jerwan, Iraq.

Sennacherib is responsible for beautifying Nineveh and bringing the capital into prominence. He built large botanical gardens for walking and even established a zoo. At that time, Nineveh was second to none and was considered the greatest city in the world for nearly 200 years. Nineveh functioned as the hub for world trade. Located at the crossroads between India and the Mediterranean world, Nineveh was visited by merchants who regularly sold their goods in the city. The Tigris River was a waterway for boats with goods for trade. Pepper and spices from India were transported across the Indian Ocean and transshipped up the Tigris and were either sold for consumption in Nineveh or shipped to points west. Caravans made their way to Nineveh to trade their goods as well. Nineveh’s merchants traded silk, blue fabric, and embroidery in exchange for spices and peppers from the East.

Sennacherib also left an account of his siege of Jerusalem in 701 B.C.E., which is carved in cuneiform characters on large stone structures in the entrance to his palace. Sennacherib records that he did not take Jerusalem, which echoes the biblical account in II Kings 18–19. His annals stated, “As to Hezekiah, the Jew, he did not submit to my yoke.” The biblical account records the miraculous overpowering of “the King of Assyria” by the mysterious “Angel of the Lord.” According to this account, the angelic warrior slew 185,000 of Sennacherib’s men. Later, Sennacherib returned to Nineveh only to be murdered by his sons, Adrammelech and Sharezer, who then fled to Ararat. Sennacherib’s youngest son, Esarhaddon, took the control of Nineveh and the Assyrian empire. He pursued his two brothers and put them to death.

Nimrod built Nineveh in approximately late eighth century B.C.E. In 1850, Layard excavated the palace of Ashurbanipal, the son of Esarhaddon, and discovered a vast library in two small chambers. On the floor of the chamber was a mass with clay tablets that had once been organized on shelves. Layard also found a crystal magnifying lens that was probably used by a librarian to read the small cuneiform text embedded in the clay tablets. A large portion of the library contained language guides like grammars and dictionaries for understanding Assyrian and Sumerian texts. This shows how advanced the Assyrian language was for that region. The library also contained works on astronomy, law, science, religion, poems, mythology, history, and records.

The ancient Mesopotamian city of Nineveh (in modern-day Iraq) was the capital of the Assyrian empire and a major trading hub from the eighth to the sixth centuries B.C.E. (© Topham/The Image Works)

In 1960, the Iraq Department of Antiquities created an on-location museum of Sennacherib’s palace and throne room. The museum is called the Sennacherib Palace Site Museum at Nineveh and is only one of two Assyrian palaces in the world (Nimrud being the other). Since the Iraq War in 2003, the museum has been seriously plundered and many of the slab-reliefs and artifacts have surfaced on the international art market.

Robert T. Leach

See also: Assyrian Empire.

Layard, Austin Henry. Nineveh and Its Remains. London: John Murray, 1849.

Pritchard, J.B. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955.

Rassam, Hormuzd. Asshur and the Land of Nimrod. Cincinnati: Curts and Jennings, 1897.

Smith, George. Assyrian Discoveries. London: S. Low, Marston, Low, and Searle, 1875.