A thick, flammable substance, ranging in color from yellow to black, which forms under the earth’s surface and contains a mixture of gas, liquid, and solid hydrocarbons. Can be separated into natural gas, kerosene, gasoline, paraffin wax, and asphalt and is used in the production of a number of other products.

Oil is formed from the decaying plants and animals that have been buried under rock for millions of years, and has been used since ancient times as fuel, primarily for lamps. Oil seeps allowed humans to gather the substance at the surface of the earth. The first attempt to dig down to the source of oil occurred in 347 C.E., when the Chinese attached bits to bamboo poles to dig down 800 feet. Persia, an oil-rich area, used oil from an early date. Marco Polo first recorded the use of oil in 1264 when he visited Baku. He noted that hundreds of ships were loaded at the same time with the oil and shipped from the Caspian Sea to other regions. Initially, oil was gathered from shallow seeps, but the Persians soon began digging down to a level of 115 feet by the late 1500s. By 1830, more than 116 drilled holes were producing approximately 700 barrels of oil. Russian engineer F.N. Semyenov drilled the first well using cable tools in the region around 1849. By the end of the nineteenth century, offshore drilling had begun in the Caspian Sea. During the Middle Ages through the age of discovery, oil was used to waterproof vessels and as a defensive weapon against invaders.

Oil was also collected from seeps in Poland and Romania around the same time. During the 1500s, oil was used from the Carpathian Mountains to light the streetlamps in the city of Krosno. Unfortunately, the oil produced a lot of smoke and a foul odor. A Polish druggist, Ignacy Lukasiewicz, used previous experiments conducted in Canada by geologist Dr. Abraham Gesner in 1849 to help him produce clean-burning kerosene. He filed for and received a patent on the process on December 31, 1853. Until then, people primarily used whale oil for lighting purposes. The problem with using whale oil was that it was expensive and its price continued to rise as an increasing number of whales were being slaughtered to meet the rise in demand. The whale population worldwide neared extinction until kerosene became the alternative source of fuel used for lighting. The demand for kerosene forced Lukasiewicz to form a partnership with other investors and the digging of 160-foot-deep wells began in eastern Europe.

Meanwhile, in the United States during the 1850s, oil seeps functioned in western Pennsylvania. A druggist sold some of this oil to a whale oil merchant, who processed it into kerosene. The druggist learned of the process and began his own distribution of kerosene. George Bissell, a New York lawyer and entrepreneur, hired Benjamin Silliman Jr. in 1854 to determine if kerosene could be produced from what the Indians called Seneca Oil. Silliman concluded that it could, and Bissell was able to obtain the financial backing of investors to form the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company, which became Seneca Oil Company. Bissell hired Edwin Drake to go to Oil Creek, where oil seeps had yielded the substance on the surface for years, to gather oil for the production of kerosene. The amount gathered was insignificant until Drake, with the assistance of a local blacksmith, began using the same steam-powered equipment used to mine brine wells. By the end of August 1859, just as Drake was running out of money, the well began producing twenty-five barrels of oil a day— an amount that would soon top off at ten barrels a day. Before long, the entire valley was covered by oil wells. The oil recovered from the wells was distilled into kerosene for use in lamps, selling at seven cents a gallon. The availability of clean burning, cheaper kerosene drove the whale oil merchants out of business—just in time to prevent the extinction of whales worldwide.

During the late 1850s and 1860s, the kerosene business boomed. Businessmen like John D. Rockefeller obtained financing to drill oil wells in western Pennsylvania. By establishing both vertical and horizontal monopolies in the industry, Rockefeller was able to drive domestic competitors from the market, while high tariff barriers prevented the importation of foreign oil that could be distilled into kerosene. Although this industry promised to be a lucrative one, the invention of the electric lightbulb by Thomas Edison in 1878 resulted in a steep decline in the kerosene business.

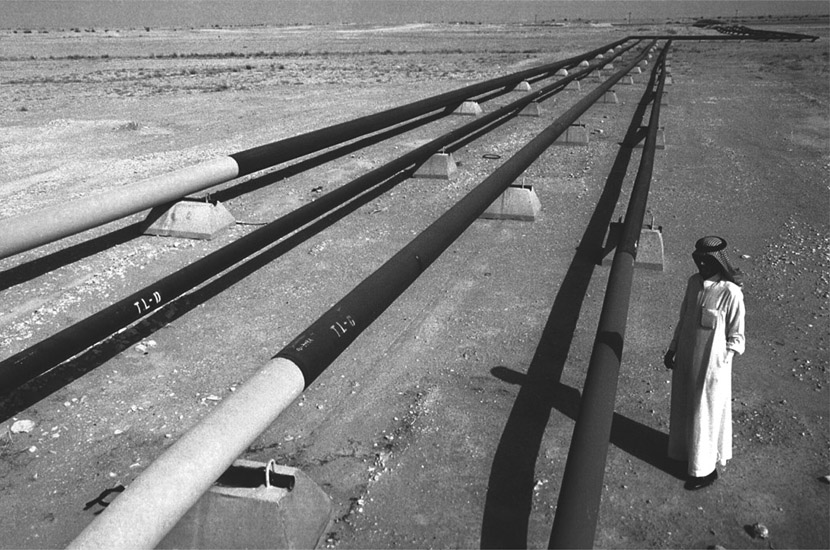

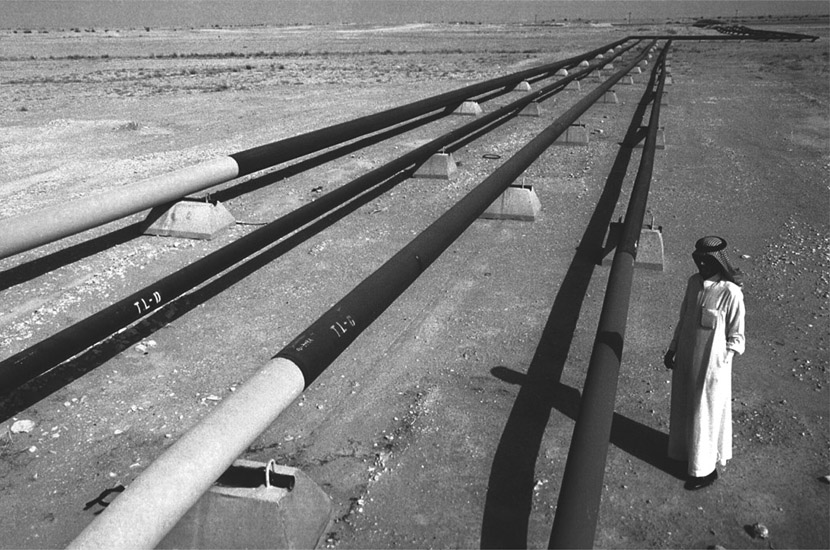

The most valuable internationally traded commodity, oil is also the major export of Saudi Arabia, which controls an estimated one-fourth of the world’s known reserves. Shown here are pipelines leading out of the country’s Howta oil fields. (© John Moore/The Image Works)

Over the next decades, homes and businesses within urban areas where electricity was affordable and accessible switched over to the cleaner, and less combustible, form of energy. The oil industry experienced a recession for the next decade until the invention in 1886 of the automobile in Germany by Karl Benz and Wilhelm Daimler. The combustion engine required the use of gasoline, a by-product of the production of kerosene. The introduction of the automobile in Europe and the United States once again increased the demand for oil, and nations scrambled to locate and develop new oil fields. Russians looked to the traditional source of oil and gas bordering the Caspian Sea, in present-day Azerbaijan. Oil companies such as Texaco, Exxon, and Mobil obtained mining rights to the oil-rich fields of Saudi Arabia for a mere $50,000 from the king.

Oil Industry in the Twentieth Century

During the 1910s and 1920s, the sale of combustion engine–driven machinery such as automobiles, tractors, and airplanes on a wider scale, especially after Henry Ford decreased the cost of manufacturing the car by introducing the assembly line to the auto industry, led to an increase in demand for oil. Demand steadily increased during the 1920s. Then the Great Depression struck. Oil was still required by industrialized nations— especially Japan, which had limited natural resources. Before World War II, the Japanese were purchasing oil from the United States. The imposition of an embargo on oil and scrap metal by the United States in 1941 forced the moderates in

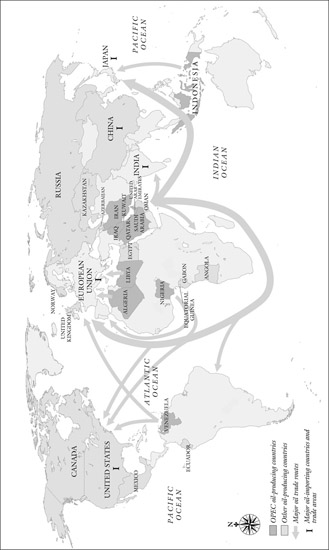

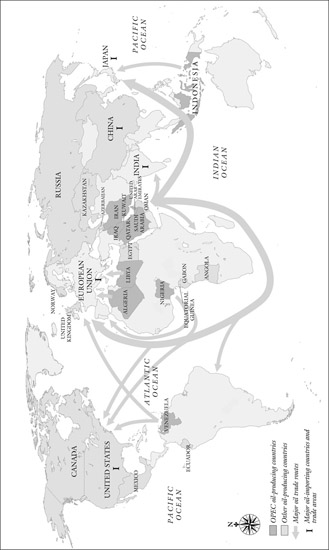

Global Oil Trade, 2004 Oil is the most valuable commodity ever traded in world history and is critical to the effective functioning of the modern global economy. The world oil trade is divided among Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), nations that set prices in concert with it, and non-OPEC producers. However, as oil is largely a fungible commodity, OPEC price-setting affects all global oil trade. (Mark Stein Studios)

Japan from power and the military implemented its plan to attack the United States at Pearl Harbor. By this time, oil had become the primary source of energy worldwide.

Although the United States benefited from major oil discoveries in western Pennsylvania, Spindletop in south Texas, and the oil-rich fields of east Texas, by the 1960s the nation imported a large percentage of its oil from Venezuela. When Congress decided to impose tariff restrictions on the importation of Venezuelan oil, the foreign nation asked for an exception, as it was the largest producer. When Congress failed to act on the request, Venezuela was forced to form an alliance with other oil-producing countries in an attempt to drive the price of crude oil up and offset the loss of volume. In the 1960s, Venezuela and most of the Arab countries formed the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). During the 1970s, OPEC reduced oil production and placed an embargo on Westernized nations. As oil prices soared and individuals waited in line for hours to pump gasoline into their vehicles, the governments of the affected nations began exploring domestic options for production. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the United States had begun drilling for oil in Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico, while England turned to exploration in the North Sea. In 1978, world oil reserves amounted to 645 billion barrels; by the end of the 1990s, that amount had increased to over a trillion barrels.

By the twenty-first century, Westernized countries were heavily dependent on oil for fuel as well as other products such as plastic. Even though nations have tapped into their domestic petroleum sources, a demand for the production of oil on a worldwide basis continues. By January 2002, over 18.5 million barrels, or the equivalent of 777 million gallons, were consumed in the United States every day. Up to 60 percent of that amount is imported and amounts to $50 billion a year in trade expenditures, the largest segment of the trade deficit. U.S. production has decreased from 8 to 9 million barrels a day in 1986 to approximately 2.9 million barrels a day in 2002. Other countries such as Russia, another oil-producing country, have experienced a similar decline in production. Saudi Arabia continues to produce 5 to 9 million barrels a day, depending on the quotas established by OPEC to protect the price of oil. Many traditional oil wells have produced less oil over the years, and new sources of oil are needed. The United States and European nations have turned to the drilling of oil wells offshore as the major source of new deposits. Attempts to increase production in Alaska have been prevented by environmental groups, who argue that the oil companies will disrupt animal life on the frozen tundra.

The increased use of plastics, from milk containers to the CD industry, continues to place a demand on the industry to meet supply. Oil is shipped from Mexico, Canada, England, Norway, Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Nigeria, Angola, and Colombia to the United States. Saudi Arabia still has the largest oil field in the world at Ghawar.

The need for oil will continue well into the future. Meanwhile, alternative sources of fuel and energy—from corn oil, to biodiesel, to solar and wind power—are being explored. Since the largest consumption comes from automobiles and industry, changes in the fuels used to power combustion engines and the ingredients used for the production of most goods must change before a shift in demand can occur. Attempts have been made, but none have proven successful on a wide scale to date.

Cynthia Clark Northrup

See also: Automobiles; Internal Combustion Engine.

Bibliography

Landes, Kenneth K. Petroleum Geology of the United States. New York: Wiley Interscience, 1970.

Mosley, Leonard. Power Play: Oil in the Middle East. New York: Random House, 1973.

Sampson, Anthony. The Seven Sisters: The Great Oil Companies and the World They Shaped. New York: Viking, 1975.

Schackne, Stewart, and N. D’Arcy Drake. Oil for the World. New York, Harper, 1960.

Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991.